* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Good Union People: Enduring Bonds Between Black and White

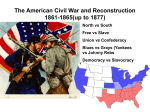

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Pillow wikipedia , lookup

East Tennessee Convention wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Jubal Early wikipedia , lookup

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

East Tennessee bridge burnings wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup