* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download impag parassit_indici.qxd

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Chagas disease wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Brucellosis wikipedia , lookup

Lyme disease wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Leishmaniasis wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Visceral leishmaniasis wikipedia , lookup

Yellow fever wikipedia , lookup

Typhoid fever wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

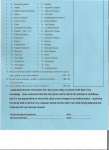

Parassitologia 48: 131-133, 2006 Epidemiology and clinical features of Mediterranean Spotted Fever in Italy A. Cascio1, C. Iaria2 1Clinica delle Malattie Infettive, Dipartimento di Patologia Umana, Università di Messina, Italy; 2AILMI (Associazione Italiana per la Lotta contro le Malattie Infettive), Università di Messina, Italy. Abstract. Mediterranean Spotted Fever is caused by Rickettsia conorii and is transmitted to humans by Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the common dog tick. It is characterized by the symptomatologic triad: fever, exanthema and "tache noire", the typical eschar at the site of the tick bite. In Italy the most affected region is Sicily. The seasonal peak of the disease (from June through September) occurs during maximal activity of immature stage ticks. Severe forms of the disease have been reported in 6% of patients, especially adults with one of the following conditions: diabetes, cardiac disease, chronic alcoholism, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, end stage kidney disease. The mortality rate may reach 2.5%. Oral or parenteral administration of tetracyclines or chloramphenicol represent the standard treatment. Recent studies indicate that oral clarithromycin and azithromycin could constitute an acceptable alternative for the treatment of the disease in children; furthermore, they could be recommended during pregnancy. Key words: Spotted Fever, boutonneuse fever, Rickettsia, clarithromycin, azithromycin. Mediterranean Spotted Fever (MSF) is a tick-borne disease caused by Rickettsia conorii. In the Mediterranean area this organism is transmitted to humans by all stages (nymphs, larvae and adults) of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Parola and Raoult, 2001). Ticks are the only vector and the main host of R. conorii being rickettsiae transmitted vertically and transovarially from females via the eggs to larvae of the next generation (Gilot et al., 1990; Parola and Raoult, 2001; Randolph, 1998; Santos et al., 2002). Dogs can be infected by R. conorii, but clinical signs of the disease have not been reported (Shaw et al., 2001). Dogs, by acting as natural hosts for R. sanguineus, significantly increase contact between these species and humans, thereby increasing the risk of transmission (Mumcuoglu et al., 1993). Interestingly, the number of cases of MSF in Italy and elsewhere appears to have increased over the past 20 years (Cascio et al., 1998; Mansueto et al., 1986; Walker and Fishbein, 1991). In Italy the most affected region is Sicily where more than half of the Italian cases are reported (Fig. 1). In Sicily an average of 6.7 cases occurred out of 100,000 people in 2004, compared with the national average of 0.9 cases per 100,000 people. The seasonal peak of the disease (from June through September) occurs during maximal activity of immature stage ticks (Cascio et al., 1998; Gilot et al., 1990). by an erythematosus halo that appear in the site of the tick bite. The onset of fever is generally sudden, and in typical cases the patients have fever >39°C. Usually exanthema follows the fever within 2-3 days and it rarely develops later than the 5th day. Exanthema is initially macular and sparse and generally it first appears on the wrists and ankles spreading rapidly to the palms and soles; it subsequently becomes maculopapular and extends to the trunk and less frequently to the face, often turning red-purple in color. In some patients only a few lesions resembling mosquito bites can be present, in others exanthema may be petechial or purpuric and rarely papulovesicular (Cascio et al., 1998; Colomba et al., 2006). The "tache noire" is present in about 70% of cases. It is generally a single lesion; the most common localizations are the scalp, the neck, and the truncus (Cascio et al., 1998). In the scalp it is often surrounded by an area of alopecia. Lymph nodes draining the skin site of the tick bite can be tender and slightly painful on palpation. Clinical features The infecting tick bite is painless, and the tick is usually unnoticed, especially when smaller larvae or nymphs are involved. When not engorged, at these stages ticks are smaller than a pinhead. A history of tick bite is an important finding but is often absent. MSF is characterized by a symptomatologic triad: fever, exanthema and "tache noire" the typical black eschar surrounded Fig. 1. Annual incidence of MSF cases (clinically ascertained) in Italy and Sicily (official reporting system, Italian Ministry of Health). 132 SOIPA XXIV - Relazioni dei Simposi Arthralgia and/or myalgia generally involve the joints and the muscles of the lower limbs, but only rarely do they restrict the mobility of the patients. Arthritis generally affects a single joint of the lower limb with moderate signs of inflammation (slight tenderness, erythema, and swelling and pain on motion). Arthralgia is more severe in adults. Headache is rarely complained of by children, while it is a typical symptom of the disease in adults (Cascio and Titone, 1987). Non-exanthematic forms can occur, and, in these cases, the only signs of infection can be the presence of lymphadenopathy and/or tache noire and/or fever (Cascio et al., 1998). Non-exanthematic forms may at least in part explain the discrepancy between the high prevalence of seropositivity and the prevalence of the disease documented in some studies (Walker and Fishbein, 1991). In the western Hemisphere, Rocky Mountain Spotted fever (RMSF), which is caused by R. rickettsii, can be a severe disease, but MSF is generally milder. Historical studies have shown that MSF can lead to 10-14 days of Fever if not treated, and that it is rarely fatal in children (Cascio and Titone, 1987). Severe forms of the disease have been reported in 6% of patients, especially adults with one of the following conditions: diabetes, cardiac disease, chronic alcoholism, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, end stage kidney disease. The mortality rate may reach 2.5%. Patients with malignant forms have a petechial rash and neurological, renal, or cardiac problems, especially elderly people (Amaro et al., 2003; Anstey et al., 1997; de Sousa et al., 2003). In an Italian series of 525 cases, complications (renal failure, myocarditis, pneumonia, encephalitis, anicteric hepatitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, anaemia and impaired glucose tolerance) were reported in 12.7% of cases (Bellissima et al., 2001). Israeli spotted fever caused by R. israeli is more severe than MSF. It is characterized by more frequent purpuric rash, thrombocytopenia, hyponatriemia and systemic complications, such as pneumonia, nephritis, encephalopathy, and occasional fatalities also in children; unlike MSF there is no "tache noire" (Anstey et al., 1997). Initially, the distribution of Israeli spotted fever rickettsia appeared to be restricted to Israel, but more recently, the organism has also been isolated from patients with MSF in Portugal (Bacellar et al., 1999; de Sousa et al., 2005) and from R. sanguineus ticks collected in 1990 in western Sicily (Giammanco et al., 2003; Giammanco et al., 2005). In the last decade newly recognized tick-borne rickettsioses have been shown to be prevalent in Europe. Lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis is a new rickettsiosis caused by R. sibirica mongolotimonae. This pathogen should be systematically considered in the differential diagnosis of atypical rickettsioses, especially rashless fevers with lymphangitis and lymphadenopathy (Fournier et al., 2000; Fournier et al., 2005). In 1997, R. slovaca, transmitted by Dermacentor marginatus tick was linked to the illness occurring especially in children and women, during the autumn and winter and characterized by an unusual crustaceous scalp reaction after receiving a tick bite and enlarged regional lymph nodes. This clinical syndrome was denominated TIBOLA (tick-borne lymphadenopathy) (Raoult et al., 2002). In some Italian series, patients that could fit the diagnosis of TIBOLA have been reported (Cascio et al., 1998; Colomba et al., 2006). And in my personal experience I have seen a patient that could fit the diagnosis of lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis (unpublished data). However, because of the scarce specificity of standard serological methods further diagnostic tests in patients with these clinical syndromes should be undertaken in the future. Laboratory findings The main laboratory findings are a slight increase of transaminases and a slight thrombocytopenia. The Weil-Felix test was the first assay used to diagnose MSF and other rickettsioses. This test lacks sensitivity and specificity. It could be used only as a first line of testing in rudimentary hospital laboratories. Today, the most commonly used serological test is the immunofluorescence antibody test (Anstey et al., 1997). Recently, a sensitive and specific PCR test based on sequences of the 17-kD protein gene (Leitner et al., 2002) and a nested PCR assay based on specific primers derived from the rickettsial outer membrane protein B gene of R. conorii have been developed (Choi et al., 2005). However, these procedures are restricted to specialized laboratories. Therapy The main feature of MSF is a generalized vasculitis with localization of R. conorii in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells (Anstey et al., 1997). Effective intracellular concentrations of antimicrobials are therefore considered the "sine qua non" for a successful treatment for this disease. Standard treatment for MSF was the oral or parenteral administration of tetracyclines or chloramphenicol. However, both of these drugs can have significant adverse effects in children. Recent studies indicate that oral clarithromycin and azithromycin could constitute an acceptable alternative for the treatment of the disease in children (Cascio et al., 2001; Cascio et al., 2002); furthermore, they could be recommended during pregnancy. In case of neurological signs, tetracyclines (minocycline or doxycycline) or chloramphenicol should be given at any age. References Amaro M, Bacellar F, Franca A (2003). Report of eight cases of fatal and severe Mediterranean spotted fever in Portugal. Ann N Y Acad Sci 990: 331-343. Anstey NM, Tissot Dupont H, Hahn CG, Mwaikambo ED, McDonald MI, Raoult D, Sexton DJ (1997). Seroepidemiology of Rickettsia typhi, spotted fever group rickettsiae, and Coxiella burnetii infection in pregnant women from urban Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg 57: 187-189. Bacellar F, Beati L, Franca A, Pocas J, Regnery R, Filipe A (1999). Israeli spotted fever rickettsia (Rickettsia conorii complex) associated with human disease in Portugal. Emerg Infect Dis 5: 835-836. SOIPA XXIV - Relazioni dei Simposi Bellissima P, Bonfante S, La Spina G, Turturici MA, Bellissima G, Tricoli D (2001). Complications of mediterranean spotted fever. Infez Med 9: 158-162. Cascio A, Dones P, Romano A, Titone L (1998). Clinical and laboratory findings of boutonneuse fever in Sicilian children. Eur J Pediatr 157: 482-486. Cascio A, Colomba C, Di Rosa D, Salsa L, di Martino L, Titone L (2001). Efficacy and safety of clarithromycin as treatment for Mediterranean spotted fever in children: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 33: 409-411. Cascio A, Colomba C, Antinori S, Paterson DL, Titone L (2002). Clarithromycin versus azithromycin in the treatment of Mediterranean spotted fever in children: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 34: 154-158. Cascio G, Titone L (1987). Rickettsiosi. In Enciclopedia medica italiana, pp. 1364-1390. Edited by P. Introzzi. Florence: Utet Edizioni Scientifiche. Choi YJ, Lee SH, Park KH, Koh YS, Lee KH, Baik HS, Choi MS, Kim IS, Jang WJ (2005). Evaluation of PCR-based assay for diagnosis of spotted fever group rickettsiosis in human serum samples. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 12: 759-763. Colomba C, Saporito L, Frasca Polara V, Rubino R, Titone L (2006). Mediterranean spotted fever: clinical and laboratory characteristics of 415 Sicilian children. BMC Infect Dis 6: 60. de Sousa R, Nobrega SD, Bacellar F, Torgal J (2003). Mediterranean spotted fever in Portugal: risk factors for fatal outcome in 105 hospitalized patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 990: 285-294. de Sousa R, Ismail N, Doria-Nobrega S, Costa P, Abreu T, Franca A, Amaro M, Proenca P, Brito P, Pocas J, Ramos T, Cristina G, Pombo G, Vitorino L, Torgal J, Bacellar F, Walker D (2005). The presence of eschars, but not greater severity, in portuguese patients infected with israeli spotted Fever. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1063: 197-202. Fournier PE, Tissot-Dupont H, Gallais H, Raoult DR (2000). Rickettsia mongolotimonae: a rare pathogen in France. Emerg Infect Dis 6: 290-292. Fournier PE, Gouriet F, Brouqui P, Lucht F, Raoult D (2005). Lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis, a new rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia sibirica mongolotimonae: seven new cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 40: 1435-1444. Giammanco GM, Mansueto S, Ammatuna P, Vitale G (2003). 133 Israeli spotted fever Rickettsia in Sicilian Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks. Emerg Infect Dis 9: 892-893. Giammanco GM, Vitale G, Mansueto S, Capra G, Caleca MP, Ammatuna P (2005). Presence of Rickettsia conorii subsp. israelensis, the causative agent of Israeli spotted fever, in Sicily, Italy, ascertained in a retrospective study. J Clin Microbiol 43: 6027-6031. Gilot B, Laforge ML, Pichot J, Raoult D (1990). Relationships between the Rhipicephalus sanguineus complex ecology and Mediterranean spotted fever epidemiology in France. Eur J Epidemiol 6: 357-362. Leitner M, Yitzhaki S, Rzotkiewicz S, Keysary A (2002). Polymerase chain reaction-based diagnosis of Mediterranean spotted fever in serum and tissue samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg 67: 166-169. Mansueto S, Tringali G, Walker DH (1986). Widespread, simultaneous increase in the incidence of spotted fever group rickettsioses. J Infect Dis 154: 539-540. Mumcuoglu KY, Frish K, Sarov B, Manor E, Gross E, Gat Z, Galun R (1993). Ecological studies on the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) in southern Israel and its relationship to spotted fever group rickettsiae. J Med Entomol 30: 114-121. Parola P, Raoult D (2001). Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis 32: 897-928. Randolph SE (1998). Ticks are not Insects: Consequences of Contrasting Vector Biology for Transmission Potential. Parasitol Today 14: 186-192. Raoult D, Lakos A, Fenollar F, Beytout J, Brouqui P, Fournier PE (2002). Spotless rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia slovaca and associated with Dermacentor ticks. Clin Infect Dis 34: 1331-1336. Santos AS, Bacellar F, Santos-Silva M, Formosinho P, Gracio AJ, Franca S (2002). Ultrastructural study of the infection process of Rickettsia conorii in the salivary glands of the vector tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2: 165-177. Shaw SE, Day MJ, Birtles RJ, Breitschwerdt EB (2001). Tickborne infectious diseases of dogs. Trends Parasitol 17: 74-80. Walker DH, Fishbein DB (1991). Epidemiology of rickettsial diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 7: 237-245.