* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Global Strategy Weekly 141110

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

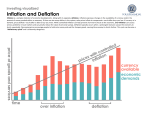

FOR INSTITUTIONAL/WHOLESALE OR PROFESSIONAL CLIENT USE ONLY | NOT FOR RETAIL DISTRIBUTION GIM Solutions-GMAG – Weekly Strategy Report 11th November 2014 Deflation fears in the eurozone ECB forecasts consistently overestimated actual inflation Lower long-run inflation expectations, which were assumed to be anchored, may partially explain this If expectations have indeed reset lower it intensifies the need for decisive ECB action Chart of the week: eurozone HICP if expectations had not dipped This document is produced by the Global Strategy Team within GIM Solutions-GMAG. For further information please contact: Editor: Patrik Schöwitz [email protected] Michael Albrecht John Bilton Michael Hood Beth Li Jonathan Lowe David Shairp Chart of the Week Our chart of the week shows how a rudimentary model of European inflation arrives at a level of current HICP ca. 1ppt higher than the actual inflation rate, if consumers’ inflation expectations are “held” static at their pre-eurozone crisis level while other variables are allowed to follow their natural evolution. In November 2011 eurozone core inflation stood at 2%, while in Japan it had dipped to -1.1%. Roll forward three years, and the impact of a decisive central bank response on deflation is clear: Japanese CPI is grinding higher, to 0.6%– according to Bank of Japan (BoJ) estimates which exclude the consumption tax hike, while Eurozone headline inflation has fallen to just 0.4%. True, the long-run effectiveness of the BoJ’s policy remains to be seen, but the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) shortcomings in fighting the threat of deflation are hard to overlook. The ECB’s dovish rhetoric last week may indeed be laying the foundations for future quantitative easing (QE), and we acknowledge that the ECB is starting to take more concrete steps, such as the TLTROs and the asset backed securities purchase programme. But to truly reverse the threat of deflation, more decisive action is likely now needed. The ECB projects low but positive inflation, with the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) forecast to be 1.2% in 2015 and 1.5% in 2016 – numbers which now look set to be revised lower. Despite the ECB’s dovish inflation forecasts, since the end of the eurozone crisis they have consistently overestimated the inflation outlook. So it is reasonable to ask whether the ECB are continuing to do so, and whether the risk of deflation is more asymmetric than is acknowledged. Our conceptual view of inflation considers three factors. First, is “supply side” inflation – proxied by food, energy and other commodities that react quickly due to the continual price discovery process in their own markets. Next is consumer “demand side” inflation – which proxies to real wages and tends to reflect the output gap. Finally, there are “inflation expectations”, which history suggests are slower moving and tend to run across several business cycles. U.S. consumers’ inflation expectations are remarkably stable; since 2000 the University of Michigan Survey of 5-10 year ahead inflation expectations fluctuated by just 0.9ppt – between 2.5% and 3.4% p.a. – despite the deepest recession since the 1930s. While there is no equivalent series in Europe, 12 month forward consumer price expectations – part of the eurozone consumer sentiment survey – suggest a steady decline in aggregate inflation expectations since the crisis. There are several possible reasons for the ECB’s overforecasting of HICP, such as incorrect estimates of the aggregate output gap and the difficulty in aggregating divergent core and periphery data. However, another plausible explanation is that aggregate inflation expectations were less well anchored than they had anticipated. In part, this may arise due to the lack of data in Europe on inflation expectations; equally it may be driven by overemphasis of the likely higher inflation expectations in core nations, relative to persistently lower expectations in the periphery. Eurozone Inflation: what might have been if expectations were stable 5 4 HICP Modelled (Consumer price expectations held at pre-Euro crisis level) HICP Modelled (Long-Run average of Consumer price expectations) HICP Modelled HICP Actual 3 2 1 0 Sources: Bloomberg, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. -1 2004 2005 2006 Note: Simple regression model of HICP from unit labour cost, blend of leading and trailing 12m consumer inflation expectations, and HICP food and energy sub components. Estimates made by holding inflation expectations static for an in sample period at i) long term average, and ii) pre-eurozone crisis level 1 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 FOR INSTITUTIONAL/WHOLESALE OR PROFESSIONAL CLIENT USE ONLY | NOT FOR RETAIL DISTRIBUTION GIM Solutions-GMAG Weekly Strategy Report Miscellaneous Musings At times of uncertain growth, a glance at IMF nominal GDP projections can be interesting. In 2015, world nominal GDP was forecast to rise by USD 4.34 trillion to USD 82.1 trillion – the equivalent of adding another Italy, Spain and Netherlands to the world economy. Staying on this theme, the bogeyman of a Chinese hard landing is never far from the surface, but if the IMF is right and China does grow nominal GDP at 10.7% next year, it will add another USD 963 billion to global output. This is the equivalent of adding another Indonesia to the world economy, and as much as the 168 smallest contributing countries to 2015 world nominal GDP growth combined. So what of the eurozone? The IMF expects a creditable USD 270 billion of nominal GDP to be added in 2015. On the face of it, not bad for a region mired by recession. But this is the equivalent of adding another Egypt to the world economy in 2015; and is just a fraction of the USD 1.6 trillion that BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India and China) are expected to add to world output next year The difference in stability of inflation expectations between U.S. and European consumers may well be due to the different approach of the Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the ECB. While few would disagree that the ECB has achieved a great deal with language alone, the Fed responded more decisively to falling inflation – when U.S. 5y5y inflation dipped below 2% in August 2010, the Fed enacted QE-2. The result was that US consumers barely had time to register the short dip in core CPI to 0.6% in late 2010, before stimulus kicked in and drove the rate back up. By contrast, European consumers suffered a combination of austerity, central bank inertia and a dysfunctional banking system for far longer, and periphery nations are now living with deflation. It seems that this backdrop weighed heavily on aggregate inflation expectations. But even then, persistently low inflation expectations do not automatically translate to deflation – the toxic combination of negative inflation levels and expectations of lower prices in the future are needed for deflation to take hold. In the last 70 years we have only one example of persistent deflation, which is Japan; elsewhere, falling prices for goods and services are not a common phenomenon. However, inflation expectations that are anchored near zero create an asymmetry of risks – a shock such as a sharp fall in energy prices, or downward pressure on wages, can quickly lead to a deflationary episode. Eurozone inflation expectations are probably now anchored at a low but positive level and, absenting ECB action, are likely to stay there. This does not inevitably mean a slide into deflation but there are unwelcome side effects. First, it leaves the eurozone vulnerable to deflation shocks – potentially a headwind for equities. Secondly, savers are likely to maintain a clear preference for bank deposits and bonds – if investors’ longer run inflation expectations are anchored at a low level, they’re more likely to view any inflationary shock as temporary and adjust their savings rate, but not the asset composition, to accommodate it. Third, low inflation expectations across the eurozone slow the pace of much needed rebalancing between the core and periphery. Finally, deflation risks threaten the recovery in indebted periphery nations and are a disincentive to capital investment. The net effect is interesting – the lack of growth stimulus and clogged credit channels in Europe leave corporations and individuals less able to benefit from the structurally low interest rates that are a consequence of low inflation. However, the internationalisation of bond markets means that Europe is effectively exporting these low rates to other regions, which can benefit from them. We believe that the U.S. in particular is seeing the manifestation of Europe’s battle with deflation in the compression of long-end Treasury yields. In turn, U.S. corporations are delivering outsized equity returns in part because of the low costs of funding. For Europe to start to benefit from the low inflation and low yield outlook, rather than simply exporting it, the ECB will need to move from words to actions. As the experience in Japan, the UK and the U.S. suggests, it is ultimately the delivery of stimulus, not the promises, that resets longer-run inflation expectations higher. On balance, we think it unlikely that the eurozone, on aggregate, will slip into deflation; but until that threat is lifted Europe’s low yields may remain more of a benefit for other regions, than for Europeans themselves. John Bilton All data sourced from JPMAM, Bloomberg, and Datastream, unless stated otherwise. NOT FOR RETAIL DISTRIBUTION: This communication has been prepared exclusively for Institutional/Wholesale Investors as well as Professional Clients as defined by local laws and regulation. The opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial markets expressed are those held by J.P. Morgan Asset Management at the time of going to print and are subject to change. Reliance upon information in this material is at the sole discretion of the recipient. Any research in this document has been obtained and may have been acted upon by J.P. Morgan Asset Management for its own purpose. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as advice or a recommendation relating to the buying or selling of investments. Furthermore, this material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and the recipient should ensure that all relevant information is obtained before making any investment. Forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes, may be based upon proprietary research and are developed through analysis of historical public data. J.P. Morgan Asset Management is the brand for the asset management business of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its affiliates worldwide. This communication may be issued by the following entities: in the United Kingdom by JPMorgan Asset Management (UK) Limited; in other EU jurisdictions by JPMorgan Asset Management (Europe) S.à r.l.; in Switzerland by J.P. Morgan (Suisse) SA; in Hong Kong by JF Asset Management Limited, or JPMorgan Funds (Asia) Limited, or JPMorgan Asset Management Real Assets (Asia) Limited; in India by JPMorgan Asset Management India Private Limited; in Singapore by JPMorgan Asset Management (Singapore) Limited, or JPMorgan Asset Management Real Assets (Singapore) Pte Ltd; in Australia by JPMorgan Asset Management (Australia) Limited ; in Taiwan by JPMorgan Asset Management (Taiwan) Limited and JPMorgan Funds (Taiwan) Limited; in Brazil by Banco J.P. Morgan S.A.; in Canada by JPMorgan Asset Management (Canada) Inc., and in the United States by J.P. Morgan Investment Management Inc., JPMorgan Distribution Services Inc., and J.P. Morgan Institutional Investments, Inc. member FINRA/SIPC. 2