* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Gabriel Tarde as a Founding Father of

Social Darwinism wikipedia , lookup

Social exclusion wikipedia , lookup

Sociology of the family wikipedia , lookup

Symbolic interactionism wikipedia , lookup

Social group wikipedia , lookup

Postdevelopment theory wikipedia , lookup

Social network wikipedia , lookup

Public sociology wikipedia , lookup

Differentiation (sociology) wikipedia , lookup

Structural functionalism wikipedia , lookup

Social development theory wikipedia , lookup

Index of sociology articles wikipedia , lookup

Sociology of terrorism wikipedia , lookup

Sociological theory wikipedia , lookup

History of sociology wikipedia , lookup

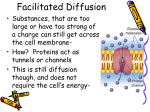

Gabriel Tarde as a Founding Father of Innovation Diffusion Research Jussi Kinnunen Department of Political Science, University of Turku Gabriel Tarde (1843-1904) has given significant contributions to to social interaction theory and to diffusion research. Diffusion refers to spreading of social or cultural cultural properties from one created his own system of society or environment to another. Tardee create( sociology, based on psychology and de signed to explain the whole of social behaviour from development of cultures to acts of an individual. In his view social change requires penetration of inventions that diffuse through the process of imitation. People imitate beliefs and desires or motives transmitted from one individual to another. Analysis should take place on a micro-level with the method he called ’interpsychology’. Tarde refuted the idea of a social whole being more than its parts. He thought at least to some extent like a reductionist. Moreover, imitation as a social phenomenon was in Tarde’s view not isolated from other activities in nature but a part of a universal law of repetition. His professional experiences in court apparently directed his interest towards criminology, affected his thinking about motives and about the level of analysis. Tarde’s ontological ideas were soon disregarded largely due to the criticism presented by Émile Durkheim (1858-1916). However, Tarde made quite a few insightful and practical observations that have benefited diffusion research. Likewise, aspects similar to Tarde’s thoughts concerning cultural evolution seem to interest modern scientists. criminology, Jussi Kinnunen, Department of Political Science, FIN-20014 of Turku, Finland © Scandinavian Sociological Association 1996 University 1. Introduction Gabriel Tarde (1843-1904) was one of the most famous sociologists in 19thcentury France. Sociologists of today remember him best as the fierce critic of Emile Durkheim - or rather as Clark puts it ’Durkheim’s whipping boy’ (1968b:509). Books on the history of sociology give much less attention to Tarde’s longer lasting contributions to criminology, social interaction theory and the subject of this article - diffusion research. Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 432 In itself diffusion - the spread of social or cultural properties from one or environment to another - is a descriptive concept. Diffusion research takes place in all major fields of social sciences. Since the 1970s interdisciplinarity has also increased. Approaches vary depending on research target, method, discipline(s). Diffusion can be scrutinized both as an independent or dependent variable. Likewise, elements of diffusion can society be emphasized quite differently. This article goes back in time to the first systematic efforts to study diffusion. It is the common heritage for all branches of diffusion research. Along with early anthro pologists, Tarde is considered to be one of the founding fathers of diffusion research. For him diffusion of inventions - or innovations - was one of the basic explanations of social change. Many of Tarde s ontological ideas were soon severely criticized and disre garded. However, his more practical observations concerning diffusion processes in Les lois de l’imitation (1890), La logique sociale (1895) and L’opposition universelle (1897) make Tarde ’undoubtedly an intellectual far ahead of his time’, as Rogers notes (1995:40). This article focuses on the following three not widely discussed questions: (1) What did Tarde say about the diffusion of innovations? (2) What general aspects of Tarde’s life might have influenced his thinking about (3) What society and social phenomena? was Tarde’s influence on later diffusion research? 2. Diffusion of innovations and ’The Laws of Imitation’ Diffusion has been of interest to curious minds long before the time of Tarde. Herodotus mentioned the phenomenon as early as 500 years before our calendar began. The founding of the New World also led to speculation about whether the American cultures had developed independently or whether they had been influenced by the Old World. The first to pay more systematic attention to diffusion were European anthropologists and ethnologists in the second half of the 1800s. (Heine-Geldern 1968:169; Rogers 1995:40ff.). Tarde accepted many of the ideas of European anthropologists, who were responsible for the introduction of the concept of diffusion to social sciences. In the second half of the 19th century anthropologists were very optimistic about finding an all-embracing meta-theory of cultural change for which diffusion would be the key (Katz et al. 1963:237). At that time, the explanatory power of natural science models was admired and the ’diffusion’ of concept was borrowed from physics, where it means interpenetration substances (Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English: 267).22 Like early European anthropologists and ethnologists, Tarde was convinced that general laws similar to natural sciences could be found for sociology as well. As he writes in the preface to the first French edition (1890) of The Laws of Imitation, it was an attempt to: ’... outline pure sociology. This is tantamount to saying a general sociology. The laws of such science, as I understand it, apply to every society, past, present, or future, just as the laws of general physiology apply to every species, living, extinct, or conceivable’ ([1903]1962:ix-x). Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 433 Tarde’s system of sociology reached its mature form in the 1890s. He had published some writings concerning imitation 1882-84 in the Revue philosophique. Systematically, however, his basic ideas are presented in Les lois de imitation, which was translated from the second edition (1895) into English as early as in 1903. It is the one of Tarde’s works that has had the most profound influence on diffusion research. Tarde’s system, based on psychology was designed to explain the whole of social behaviour from the development of cultures to social currents and acts of an individual. Tarde called his method, ’interpsychology’ or ’intermental psychology’. (Rogers 1995:40; Clark 1968b:510). In Tarde’s view major social change in societies or cultures requires penetration of inventions. They are infrequent products of genius. The guid ing principle is: the more people interact, the more likely that novel inventions will appear. (This is an idea that originates from an anthropologist, Francis Galton.) Innovations change the course of social phenomena and help people to adapt to their changing environment. Tarde also emphasized the significance of communication and human interaction in which the elite often has a pivotal role. In other words, there are those who are capable of guiding the developments and those that imitate. (Clark 1968b:510; Lukes [1973] 1992: 302 and 306; Rogers 1995:40; Tarde [1903] 1962:16-22). Inventions diffuse by process of imitation, on which the social aspect of Tarde’s system was entirely founded. In Tarde’s words ’an invention bears the same relation to imitation as a mountain to a river’ ( [1903] 1962:3). Whereas inventions are rare (landmarks) in human conduct, most of the human action could be explained by (the flow of) imitation. People imitate beliefs and desires or motives that are transmitted from one individual to another. Beliefs and desires form the raw material in social interaction by which personalities evolve. Tarde insisted that focus on the analysis of social phenomena should be on micro- level, coming back to the individual. Therefore, it seems that he thought methodologically, at least to some extent, like a reductionist (Lukes [1973] 1992:57, 302-303 and 312-315). Tarde did not study imitation as a social phenomenon isolated from other activities in nature. Philosophically, Tarde saw imitation as part of a universal law of repetition. In his introduction to The Laws of Imitation Franklin H. Giddings describes: ’(for Tarde) ... imitation ... is only one mode of a universal activity, of that endless repetition, throughout nature, which in the physical realm we know as the undulations of ether, the vibrations of material bodies, the swing of the planets in their orbits, the alterations of light and darkness, and of seasons, the succession of life and death. Here, then, was not only a fundamental truth of social science, but also a first principle of cosmic philosophy’ (Tarde [1903] 1962:v). He called the analogous laws to imitation in physics undulation and generation in biology. Tarde explained more specifically his ideas about the universal law of repetition in La Logique sociale (1895). Tarde observed that inventions usually diffuse from their geometrical centre as waves from the point where an object hits water. Diffusion has an areal centre - usually a resourceful one - from which the spreading starts. However, he did not rule out the possibility that environment could distort Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 434 the effect (Tarde [1903] 1962:22, 102 Clark 1968b:510). Furthermore, Tarde wondered why out of one hundred innovations only ten will spread while the other ninety will be forgotten ([1903]1962:140). This led him to think of (a) logical laws, and (b) extra-logical influences of imitation. Logical laws of imitation bear the thought that innovations logically parallel to the rational aspects in a given culture spread more readily than the ones that are not (Tarde [1903] 1962:ch 5). The use of inventions that are either too complex or simple for a given society does not usually spread. The aid and development programmes of the developing countries are a showcase presenting plenty of examples of this. Tarde also found three extra-logical influences of imitation that are (a) from inner to outer man, (b) from superior to inferior, and (c) the transition from custom to fashion ([1903]1962:ch. 6). The first of the extra-logical influences means that imitation begins within an individual: effects precede cognition which precedes action. In his view dogmas are transmitted before rites, ideas communicated before expression and purposes before means did not attempt a ([1903]1962:ch. 6:i). Lukes accurately notes ’(Tarde) of imitation but took it as his psychology starting-point ([1973] 1992:303)’. The second extra-logical influence means that innovations created by social superiors are more likely to be adopted than the ones created by inferiors. He also noted that distance has an effect: the most superior among the least distant is the one imitated. Finally, Tarde discussed the effect of social currents that affect all areas of a society (Tarde [1903] 1962 ch. 6:ii). Tarde studied large-scale statistical material over long periods of time. He had great difficulty in realizing his objectives with his approach and method. Tarde criticized the French governmental statistics for not having data on people’s values, religious activities, linguistic change or emotional attributes, beliefs or desires (Tarde [1903] 1962 xvi, 14-16 and 140ff.; cf. Clark 1968b:510-511.) It was not until two-three decades later that such surveys and polls were first made by the behaviourist school. Tarde also realized some of the significance of counter-cultures and conflict. In 1897 he devoted an entire study to the subject L’opposition universelle. As the first edition of The Laws was published in 1890 he had already observed that innovations are often modified or re-invented in the course of the diffusion process ( [1903] 1962:22) and that they need to fit the existing culture or environment ([1903 1962:151-154). Moreover, he mentioned the element of conflict in the preface. He wrote that there are two ways of imitating: to act exactly like one’s model or just the opposite, which may result in a controversy ( [1903] 1962: xvii). In L’opposition his perhaps more profound ideas were that within individual minds conflict may result in environmentally adaptive inventions, that is, in positive change. Social conflicts occur when people presenting different inventions come into contact with one another. The intensity of the conflict increases if it is an issue of morality, economics or politics and if the problem is of a specific nature. Tarde saw morality primarily as a personal issue, whereas economic matters had broader consequences on subsectors of a society. Political issues have the greatest influence on a society and, therefore, they also create the greatest conflicts. (Cf. Clark 1968b:510-511.) ... Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 435 3. General aspects of Tarde’s work and life Tarde’s background and life naturally affected his thinking concerning society and social issues. He was born in Sarlat, Dordogne, France in 1843 to a noble family and was the only child. Tarde received a classical education at the local Jesuit school. As an adult, however, he was not particularly religious compared with his peers. Tarde obtained a secondary degree in the humanities and studied law at the University of Toulouse and Paris. He became interested in sociology when he was a magistrate in the region of Sarlat where he stayed until his mother died in 1894. In the same year he began to work as a director of the criminal statistics office in the Ministry of Justice in Paris. Tarde held the post until his death in 1904. As for his academic engagements, it can be mentioned that he was a member of the Institut International de Socaologie.3 Tarde was named Professor of Modern Philosophy in the College de France in 1900 even though he lacked a doctor’s degree. (Clark 1968b:509-510.) Tarde spent most of his life outside of Paris and the university system. This may be one of the reasons that as a professional Tarde has been described as being ’something of a dilettante, who dabbled in literary activities and frequented Parisian sczlons’ (Lukes [1973] 1992:304). Furthermore, his interest in social phenomena started out from academic circles, in court. This quite apparently affected his thinking at least in three ways: (1) It directed his interest towards criminology. He first became known as an expert on criminology through his writings in La criminalité comparee and La philosophie pdnale. (Clark 1968b:509 and 513.) (2) It affected his thinking about motives. Interest in beliefs and desires was undoubtedly influenced by his occupation in court, where he faced repeated similar crimes with the same motives on a daily basis. Court experience might have been a factor in directing his interest towards psychology (Clark 1968b:510-511; Giddings 1903:iii vii and Lukes [1973] 1992:302). (3) It had an impact on his thinking concerning the level of analysis. In court Tarde dealt primarily with individuals. This may have led him to think like a methodological individualist. He acknowledged no social whole: everything social could be reduced back to individuals who are responsible for their own actions, one might add. (cf. Lukes [1973] 1992: 302 306). Many his of Tarde’s own writings were greatly influenced by his attempts to defend system of pure sociology and his aim of establishing sociology as an in the sisterhood of sciences. There were disputes about the lines of demarcation against other disciplines but also within the field of sociology itself. For twenty years Tarde crusaded against biologisms in sociology. He reacted against Espinas, Worms (whom he converted), de Greef, Gumplowicz, Novicow, Lombroso, Lilienfeld and Roberty (Lukes [1973] 1992:302). However, as Clark points out, rather than succeeding in making a difference in every respect be tween sociology and natural sciences: ’Tarde’s &dquo;transformationism&dquo; was a refined and qualified evolutionary theory, and near the end of his life he was willing to admit that he had independent discipline Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 436 resorted too frequently to biological explanations in earlier works’ (1968b:513). The lines of demarcation between sociology and philosophy were likewise blurred in Tarde’s writings. In part, this was due to Tarde’s style of literary expression. In this respect the means tended to prevail over ends: verbally, he was extremely talented. Emile Durkheim (1858-1916), at that time a full professor at Bordeaux, commented on Tarde’s approach when Tarde was appointed to the chair of Modern Philosophy. He said: ’I deeply regret, for the sake of both sociology and philosophy, both of which have an equal interest in remaining distinct, a confusion which shows that many good minds still fail to understand what each should be’ (Lukes [1973] 1992:304). Within the field of sociology Tarde had the most serious, over a decade with Durkheim, for which he has become famous among the The dispute was started by Tarde in a review of Division of Labour in 1893. The culmination of the dispute took place in 1903-1904 at the Ecole des Hautes Études Sociales where both Durkheim and Tarde were giving lectures on ’Sociology and the Social Sciences’. At the third meeting they debated face-to-face (Lukes [1973] 1992:57 and 302ff.). Both Tarde and Durkheim believed they had found the correct ontological view of sociology. Tarde believed that society was simply an aggregate of its individuals that should be studied on micro-level with a psychological method and the focus should be on imitation. Durkheim struck the other extreme, claiming that society is a reality in itself, ’a whole is greater than its parts’. Tarde thought this was metaphysics or mysticism. Durkheim thought of psychological facts as basically inherited phenomena and, therefore, uninteresting (Ritzer 1988:70). He stated that social facts were to be explained on the social level and he wanted to keep the distinction clear. For generations to come Durkheim offered numerous pieces of concrete sociological research and methodological advice. In Tarde’s works the sparks were rather well hidden in the ashes of his obscure approach and somewhat circular reasoning. One of his worst problems was in having to explain away the information that contradicted his theories. As much as Tarde’s work was full of insightful and significant observations, he failed to create the means for scientific research. long debate sociologists. 4. Tarde’s influence on diffusion of innovations research After Tarde’s death one could talk of a scientific discontinuity in the field of sociological diffusion research for nearly forty years. One reason for the discontinuance might have been the fact that sociologists’ attention was diverted into the field of communication. Another reason was that there were no methodological tools available until much later. The third reason was that Durkheim became the authority in the field of sociology in France (Clark 1968a:37-71). He was largely responsible for the teaching of sociology because of his status as Professor of the Science of Education. His views prevailed. However, Tarde’s ideas found support in America by the Chicago School, for instance. He influenced Robert Park, Edward Burgess, but also others like E. A. Ross, J. M. Baldwin, C. H. Cooley, F. H. Giddings, Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 437 anthropologists like F. Boaz and Chapin, the sociologist (Clark 1968b:509; Katz et al. 1963:237-252; Lukes [1973] 1992:303; Rogers 1962:52-55.) After the devastating World War I, social sciences developed faster in the United States than in Europe. Translation of The Laws into English as early as 1903 gave the Americans access to Tarde’s thinking. Moreover, he was not the only sociologist to write about imitation. Georg Simmel became well known in America and influenced the thinking of early sociologists there, especially the study of social interaction (cf., e.g., Ritzer 1988 :141161). He hinted at the imitation tradition in his well-known study Fashion (Simmel [1904] 1971). The subject was very suitable for an imitation study and the booklet has never gone ’out of fashion’. Tarde’s ideas concerning diffusion were eventually noted by rural sociologists. Especially influential was the study by Ryan & Gross on the spread of hybrid corn innovation in Iowa (1943). In the 1920s and 1930s however, there were also a few empirically oriented diffusion studies made, for instance, on city-manager plan, on a third-party movement and on amateur radio. From the 1940s until 1960s the popularity of diffusion research rose within different disciplines simultaneously and independently. Scholars were unaware of the fact that they were preoccupied with the same idea. Studies emerged, for instance, from the fields of anthropology, rural soci ology, education, medical sociology, general sociology, communication, marketing and geography. In 1941 there were 27 studies and 423 in 1959 (Katz et al. 1963:238-240; Rogers 1995:45). In the 1960s researchers of different fields became aware of other’s activities. This was also reflected in the number of diffusion studies - even though the increase can at least partly be explained by the fact that social sciences were emancipating in general. From 1959 until the end of the 1960s the number of diffusion studies had more than quadrupled: in 1969 there were 1,799 studies available (Rogers 1995:45). Much of the credit for the awareness must go to Everett M. Rogers and his book Diffusion of Innovations (1962). He studied the different diffusion traditions in the spirit of logical empiricism and attempted to create a synthesis out of their very versatile research findings. His books - Diffusion of Innovations in 1962, Communication of Innovations with F. Floyd Shoemaker (1971) and Diffusion of Innovations in 1983 and in 1995 (4th edition) - are perhaps the most cited works in all of the diffusion literature. Interestingly enough, Rogers was well aware of the writings of Tarde. Many of his generalizations are in harmony with Tarde’s principles. All along Tarde’s most striking ideas had to do with practical observations rather than ontological questions of what society and sociology are all about. In contemporary diffusion terms imitation could be called adoption of an innovation (Rogers 1983:40). The present diffusion studies do not see adoption as part of a system of such large scale as that of Tarde was. It is not considered preferable, either. On a practical level Tarde’s principles are often still valid, however. An illustration can be found in Tarde’s own example of coffee innovation (Tarde [1903] 1962:20-22) supplemented with the ideas that Rogers presents in his book in 1983. The increasing number of coffee consumers can be graphically portrayed with an S-shaped diffusion curve, which Tarde had already realized. It Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 438 ..................- Figure 1. An imaginary S-shaped diffusion curve of coffee innovation and adopter categories. Source: Rogers (1983:247). 1 that over time only a few people adopt a new innovation at first. For rich people start enjoying coffee. According to Tarde s logical law it would fit their culture and resources better those the one of the poor. Then, the innovation becomes famous. According to an extra-logical principle, by drinking coffee the rich and famous set an example to be followed. Therefore, as the number of adopters (imitationists) increase greatly, prices sink and coffee becomes available for everyone. Finally, after most of the people have adopted the innovation, the number of new adopters decreases. Statistically observed, the accumulative number of adopters changes over time in a manner that forms the S-shaped diffusion curve (cf. Rogers 1995:11 and 40). Diffusion curves are still usually S-shaped. In current research diffusion is often seen as a communication process with distinct stages through which innovations spread. Channels of communication link a source or emitter to an adopter. Those producing innovations are called innovators, those enhancing diffusion are called change agents and those receiving an innovation are called adopters. In present studies an innovation may be almost anything novel, e.g., an idea, a practice, or an object. Moreover, an innovation need not even be objectively new. Usually they are novel for the adopter. Adoption may be illustrated by adopter categories as presented in Figure 1 - quite according to Tarde’s original ideas (McAdam & Rucht 1993:59; Rogers 1983:5, 11 and 247; Uhlin 1995:33). Tarde had also realized that a very important question in diffusion is that of adoption decision-making and also taking into account the adverse means example, Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 439 Figure 2. Positive connotations of innovations. alternative of possible rejection. Many of the later diffusion studies feature success stories of innovations that have been widely adopted and become popular. These studies have been made ex post facto and, therefore, the result is already known. From the point of view of research planning and economy studying, these cases are well argued for: subjects are researchable and many of them can be regarded as undeniably significant.4 An acknowledged problem is that the word ’innovation’ has also a hidden meaning or connotation: it is something good. Frequently, studies have had as a point of departure an assumption that the innovation in question should be diffused and adopted by all members of a social system, that it should be diffused more rapidly, and that the innovation sjaould be neither re-invented nor rejected. This problem is known as the ’pro-innovation bias’. Another reason for the bias is that a lot of the research is funded by sources that are interested in hastening the diffusion. Therefore, the selection of innovations may be implicit, latent, and largely unintentional (Rogers 1983:92-93 and 103ff.). Today diffusion research takes place in all the fields of social sciences in all parts of the world. Furthermore, since the late 1970s and 1980s diffusion research has become more and more interdisciplinary by nature. Another feature for diffusion research seems to be that most of the studies are practice-led rather than theory-led. Hblttd estimates that two-thirds of all studies are empirically orientated (1985:7). Many of the contemporary studies come from the fields of business and economics, education, health sciences, political science and public administration, but also from sociology. One of the recent developments seems to be the growing interest in technology transfer as a factor of social change. Although the growth rate of diffusion studies has remained unchanged from the mid-1980s, there are over 4,000 diffusion studies available today5 (Rogers 1995:45). An interesting recent development is that in future(s) studies attempts have been made, for instance by biologist Vilmos Csdnyi (1989), to build theories or evolutionary models that would solve problems of a biological and social nature by studying them together as a systemic entity. Biosphere including human societies - should be observed as a whole. Some interesting Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 440 parallel thought patterns can be found with Gabriel Tarde (cf. Csdnyi 1989: ch. 7). For instance, Csdnyi discusses the proposition of Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman (1978,1981) that an invention has the same effect on the development of cultures as mutation has in genetics ( 1989:155ff. ). Tarde writes : ’... human invention ... stands in the same relation to social science as the birth of a new vegetal or mineral species (or, on the hypothesis of a gradual evolution, of each of the slow modifications to which new species is due) to biology ([1903] 1962:11).’ First version received November 1995 Final version accepted June 1996 Notes 1 Karvonen examines diffusion studies of political science point of view (1994:109-115). Rogers also presents a table from this (1983:80-81). 2 Diffusion is not the only word that anthropologists and used for describing the spread of social properties or convergence of cultures. Parallel concepts were, e.g., acculturation and modernization. However, ’diffusion’ as a concept may be understood to be more restricted than the two in both continuity and intensity (Heine-Geldern 1968:169). 3 Institut International de Sociologie was founded by René Worms in the mid-1890s. Worms was an adversary of Durkheim and Tarde was part of Worms’s large society of scholars, both professional and amateur, which included scholars such as Kovalevsky, Novicow, de Roberty and Richard (Clark 1968b:37-38; Lukes ethnologists [1973] 1992:393). 4 George F. Ray, for instance, in his study Innovations Diffused - A Random Walk in History (1991) emphasizes the impact innovations have had for change in the course of history. For ex post facto problems, see also Rogers (1983:92ff.). 5 There are several sources where compiled information on diffusion literature is available. Both Stanford University and Ohio State University house diffusion libraries. The former concentrates on communication literature and the latter on geography. Moreover, the University of Michigan (UMI) has a database available. According to the database there are approximately 30 dissertations written on diffusion of innovations (with these concepts) annually in the 1,300 universities that are within the database (UMI: Dissertation Abstract Ondisc. DAI Volumes 48/7-53/6 and 53/7-54/6). At present the most popular fields seem to be Business and Economics, Education and Health Sciences, whereas in the beginning of 1980s the alltime favourite was Rural Sociology. Most of the studies deal with techn(olog)ical innovations. Furthermore, Musmann & Kennedy have compiled an interdisciplinary bibliography on the subject which includes a chapter on Sociology (1989:171-178). Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 441 References Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. & Feldman, M. W. 1978. Toward a Theory of Cultural Evolution. Interdisciplinary Science Review, 3, 99-107. Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. & Feldman, M. W. 1981. Cultural Transmission and Evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Clark, T. N. 1968a. Émile Durkheim and the Institutionalization of Sociol ogy in the French University System. European Journal of Sociology, IX, 37-71. Clark, T. N. 1968b. Gabriel Tarde. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 15, pp. 509-514. USA: The Macmillan Company & The Free Press. Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English 7th Edition 1982. Csányi, V. 1989. Evolutionary Systems and Society: A General Theory of Life, Mind and Culture. Durham: NC Duke University Press. Giddings, F. H. [1903] 1962. Introduction in Laws of Imitation by Gabriel Tarde. New York: Holt. Heine-Geldern, R. 1968. Cultural Diffusion. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 4, pp. 169-173. USA: The Macmillan Company & The Free Press. Hölttä, R. 1985. Innovaatioiden tutkiminen 1980-luvulla. Helsinki: Helsingin kauppakorkeakoulun julkaisuja D-68. Karvonen, L. 1994. Diffusionproblemet i studiet av komparativ politik. Politiikka, 36, 2, 109-115. Katz, E., Levin, M. L. & Hamilton, H. 1963. Traditions of Research on the Diffusion of Innovation. American Sociological Review, 2, 237-252. Lukes, S. 1973. Émile Durkheim. His Life and Work: a Historical and Critical Study. Allen Lane. Reprinted with updated Bibliography in Penguin Books 1992. McAdam, D. & Rucht, D. 1993. The Cross-National Diffusion of Move ment Ideas. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 528, 56-74. Musmann, K. & Kennedy, W. H. 1989. Diffusion of Innovations. A Select Bibliography. Bibliographies and Indexes in Sociology, No. 17. New York - London - Westport: Greenwood Press. Ray, G. F. 1991. Innovations Diffused - A Random Walk in History. Helsinki Research Institute of the Finnish Economy, Discussion paper No. 385. Rogers, E. M. & Shoemaker, F. F. 1971. Communication of Innova tions. New York: The Free Press. Rogers, E. M. 1962. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: The Free Press Rogers, E. M. 1983. Diffusion of Innovations. Third Edition. New York: The Free Press. Rogers, E. M. 1995. Diffusion of Innovations. Fourth Edition. New York: The Free Press. Ritzer, G. 1988. Sociological Theory. Second Edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Ryan, B. & Gross, N. C. 1943. The Diffusion of Hybrid Seed Corn in Two Iowa Communities. Rural Sociology, 8, 15-24. Simmel, G. [1904]1971. Fashion. In D. Levine (ed.), Georg Simmel, pp. 294-323. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016 442 Tarde, G. [1903]1962. The Laws of Imitation. Clouchester, Massachusetts : Peter Smith by permission of Henry Holt & Company. Tarde, G. 1897. L’opposion universelle. Paris: Alcan. Tarde, G. 1895. La logique sociale. Second Edition. Paris: Alcan. Uhlin, A. 1995. Democracy and Diffusion. Transnational LessonDrawing among Indonesian Pro-Democracy Actors. Lund: Political Studies 87. Downloaded from asj.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on February 18, 2016