* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Hemodynamic modeling in human left ventricle

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Echocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Artificial heart valve wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

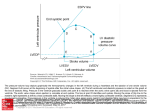

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2003 Hemodynamic modeling in human left ventricle Kwamina Bedu-Amissah Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bedu-Amissah, Kwamina, "Hemodynamic modeling in human left ventricle" (2003). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 776. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bedu-Amissah, Kwamina Hemodynamic Modeling in Human Left Ventricle May 2003 Hemodynamic Modeling in Human Left Ventricle By Kwamina Bedu-Amissah A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee Of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science III Chemical Engineering Lehigh University 4/25/03 Table of Contents List of Tables --------------------------------------- List of Figures -------------------------------------- Abstract -------------------------------------- Chapter 1 - Echocardiography --------------------------------------- Pg. 2 Chapter 2 - Doppler Echocardiography --------------------------------------- Pg. 3 Chapter 3 - Circulation in Heart ---------------------------------------- Pg. 5 Chapter 4 - Research --------------------------------------- Chapter 5 - Results and Discussion Patient I --------------------------------------- Pg. 14 Patient 2 -------------------------------------- Pg. 18 Chapter 6 - Direction of Research -------------------------------------- Pg. 22 111 IV Pg. I Pg. 8 Appendix Appendix A - Patient 1 -------------------------------------- P g. 23 Appendix B - Patient 2 -------------------------------------- Pg. 26 Bibliography- -------------------------------------- Pg. 30 Vita ---------------------------------~----- 11 Pg. 31 List of Tables Table 1- Patient 1 ventricular volume from beginning to end diastole --- Pg 15 Table 2- Patient 2 ventricular volume from beginning to end diastole --- Pg 19 111 List of Figures Figure 1: A Schematic and Real Doppler Echocardiography showing the fourchamber apical view -- Pg. 4 Figure 2: Schematic diagram showing pathways of blood flow in human heart-Pg.5 Figure 3: Pressure-Volume relation in left ventricle -- Pg. 3 Figure 4: Patient 1 A and E peak information showing variation of 2-D volumetric flow rate across mitral valve vs % Total Diastolic Time -- Pg. 11 Figure 5: Patient 2 A and E peak information showing variation of2Dvolumetric flow rate across mitral valve vs % total Diastolic Time -- Pg 11 Figure 6: Patient 1 A& E peak information -- Pg. 14 Figure 7: Patient 1 - Schematic diagram showing left atrial and ventricularmovement -- Pg. 15 Figure 8: Blood flow in left ventricle after time steps (a) 2 and (b) 50 -- Pg. 16 Figure 9: Blood flow in left ventricle after time steps (c) 150 and (d)350 -- Pg. 17 Figure 10: Patient 2 A& E peak information -- Pg. 18 Figure 11: Patient 2- Schematic diagram showing atrial and ventricular movement -- Pg. 19 Figure 12: Blood flow in left ventricle after time steps (a) 2 and (b)100 -- Pg. 20. Figure 13: Blood flow in left ventricle after time steps (c) 200, (d) 300 and (e) 400-Pg.20 IV Abstract Heart failure is amongst the leading causes of death in all age groups around the world. Modifications in the mechanical properties of cardiac tissue are due to the effects of hormones, aging, unhealthy diets, smoking and others. These cause alterations in the heart structure and hemodynamic properties, ultimately leading to heart failure. In this study, the primary aim is to investigate the effect of left ventricular shape on blood flow patterns. This will make it possible to study the interaction between blood components and heart wall surface. Depending on the flow patterns, blood components can be convected or diffused into the heart wall tissue. The rate of transport depends on the heart shape since diffusive or convective velocity is a function of ventricular shape. It is believed that a hormone component ofthe blood, Angiotension II (ang II) is one cause of hypertension. It docks on certain receptor sites on the wall and instigates reprogramming of cardiac gene expression, resulting in cellular and molecular changes. Sections of the heart wall with high normal velocity to it will tend to absorb more hormones, thereby are more likely sites for the initiation of hypertension and subsequent hypertrophy. In this work, ventricular wall velocities obtained from patient cine-angiograms are used to simulate blood flow patterns in the heart of a male and female patient. Since the heart wall absorbs the hormones during the filling of the heart, only the period of time for isovolumic relaxation and filling of the left ventricle is simulated. Evaluation of the blood flow patterns employed a finite difference method to solve the Navier-Stokes equation. Patient ventricular cavity volumes are also determined. 1 Chapter 1 Echocardiography Echocardiography (ultrasound imaging) is a non-invasive tool for imaging the heart as well as its internal and surrounding structures. The basis of ultrasound imaging is reflection oftransmitted waves from internal organs of the body. Ultrasound transducers using piezoelectric crystals generate sounds waves that are mechanically or electrically swept across a tomographic plane (Otto and Pearlman [1] - Pg. 10). The reflected waves are received by the transducer's piezoelectric crystal. The ultrasound waves used have frequencies of 1-20MHz and travel at about 1540rn/s in soft internal organs. Since speed is a function of medium density, this value increases considerable for higher dense organs such as in bones. The usefulness of echocardiography is limited by the quality of the images that are obtained from the patient. Air-free contact between the transducer and body is necessary by using gels to form an airless contact. The transducer's position is adjusted to find the best acoustical window allowing clear visualization of the heart. Also, the depth of penetration of the wave into the body is directly related to wavelength. The shorter the wavelength, the shorter the penetrating distance and vice versa. Thus, depending on what internal organ is being examined, one can use shorter wavelength (higher frequency, lower depth penetration but decent image resolution) or longer wavelength (lower frequency, higher depth penetration but mediocre resolution) (Otto and Pearlman - [1] Pg. 2). Optimal return of reflected ultrasound occurs at a perpendicular angle (90 of incidence. Small structures result 0 ) in scattering of the ultrasound signal instead of reflection. 2 Chapter 2 Doppler Echocardiography The basis of Doppler Echocardiograph is scattering of ultrasound from moving blood cells. Even though red blood cells are individually much smaller than the wavelength of the sound waves used (7-10Jlm radius), detectable scatter occurs due to thousands of blood cells being present in the path of the beam (Otto and Pearlman [1] Pg. 4). A stationary target of dimension smaller than the wavelength of the beam will scatter ultrasound in all directions, with the frequency of the scattered signal being the same as the transmitted when observed from any direction. On the contrary, a moving target will backscatter ultrasound to the transducer so that the frequency observed when the target is moving toward and away from the transducer is higher and lower than the original transmitted frequency respectively. The difference in frequency between the transmitted and backscattered signal received at the transducer is the Doppler shift, shown in the Doppler equation below: DopperShift = c(F -F ) s r 2Fr(cosE» (1) Where c is the speed of sound in blood, FT and Fs are the transmitted and backscattered frequencies respectively, e is the intercept angle between the ultrasound beam and direction of blood flow. The multiplying constant 2 is a correction factor for the transit time both to and from the scattering source (Otto and Pearlman [1] Pg. 14). When the backscattered signal is received at the transducer, the difference between the transmitted and backscattered signal is determined by comparing the two waveforms using Fast Fourier Transform. 3 Below in Figure 3 is a schematic and real four-chamber Doppler echocardiograph image of a human heart. The first figure is labeled to show the left atrium (LA), right atrium (RA), left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV). The closed mitral and tricuspid valves can also be seen in the left and right ventricles respectably. Figure 1: A Schematic and Real Doppler Echocardiography showing the fourchamber apical view. 4 INTENTIONAL SECOND EXPOSURE Below in Figure::; is a schematic and real four-chamber Doppler echocardiograph image of a human heaJ1. The first figure is labeled to show the left atrium (LA). right atrium (RA). left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV). The closed mitral and tricuspid valves can also be seen in the left and right ventricles respectably. Figure 1: A Schematic and Real Doppler Echocardiography showing the fourchamber apical view. 4 Chapter 3 Circulation In Heart PUlMONARY ARTeRY lEfT AmlUM ONE·WAY V~VES (J:lE.WAY V~VE AIGIff ATRIUM ONE·WAY VAlVE LEFT RIGIff VENTRIClE VENTRIClE Figure 2: Schematic diagram showing pathways of blood flow in the human heart Figure 2 above is a schematic diagram of the heart illustrating its chambers, blood vessels and direction of flow of blood. It is a hollow organ with four chambers and muscular walls (myocardium). The right atrium collects deoxygenated blood from the body. When the atrial pressure exceeds that of the ventricle's, the tricuspid valve is forced open and blood flows into the later. The increased ventricular pressure pushes the pulmonic valve open and blood is pumped at low pressure into the lungs by way of the pulmonary artery. Oxygenated blood returning from the lungs through the pulmonary veins is collected in the left atrium before being delivered to the left 5 ventricle via the mitral valve (diastole). The left ventricle then pumps oxygenated blood at high pressure to the rest of the body by way of the aorta (systole). During diastole, the left ventricular wall-thickness is 20-30% ofthe external cardiac radius. The inner wall of the ventricle is irregularly corrugated by longitudinal columns of muscle of varying thickness. The papillary muscles project into the cavity to complicate its shape (Caro et al. [2] Pg. 208-209). An example of a pressure - volume relation in the left ventricle is shown in Figure 3 below: 200 ""' a. ~ ~ .....E .. -- .. ...d> 100 ~ ~ Q) (.Q - q;. a.. ( /' ... EJ ' \ ~ t I tiC IRl r o o.l--~~==::===--~~ o 100 ~O WO I VentrIcular volume (em') Figure 3: Pressure-Volume relation in left ventricle (adopted from Milnor [8]) The notation is as follows: The D-curve depicts diastolic filling. During this time, blood passively fills the left ventricle from the atrium, followed by an additional (smaller) volume due to atrial contraction. It is characterized by the mitral valve opening whilst 6 the aortic valve is closed. Pressure changes are low but the volume increases immensely (almost doubles). Curve IC portrays isovolumic contraction. Ventricular pressure highly increases. The mitral and aortic valves are closed. Curve EJ shows the period of ejection of blood from left ventricle. Higher pressure in the ventricle than in aorta causes the aortic valve to open and blood flows into arterial system. This is coupled with mitral valve being closed, little pressure changes and high volume decrement. Finally, the IR Curve illustrates isovolumic ventricular relaxation (systole). Mitral and aortic valves are closed and the ventricular pressure decreases greatly. Doppler echocardiography measurements of the flow across the mitral valve show two peaks: an early peak velocity (E wave) reflecting passive diastolic filling and a late peak velocity due to atrial contraction (A wave). The normal E and A velocity in healthy young individuals are about 1.0 m/s and 0.2 to O.4m/s respectively (Otto and Pearlman [1] - Pg. 55). With aging, there is a gradual reduction in E velocity and an increase in A velocity such that the ratio of E to A velocity changes from> I in young individuals, to about 1 at ages 50 to 60, to < 1 in older normal individuals. 7 Chapter 4 Research Work Doppler echocardiograph images of two patients were analyzed. It has been found that the most useful images were those showing the apical 2-chamber or 4-chamber views because there are few intrusions (artifacts), such as from the papillary muscles. The computation follows that outlined in Macpherson and Neti [7]. It is done on three levels namely: I) Continuum Scale: This involves macroscopic flows in the left ventricle. It uses a two-step finite difference method to solve the Navier Stokes. The continuity equation is used to develop the configuration of the source. The source is placed in the middle of the atrium. Sinks are also place around the ventricle to ensure conservation of mass. 2) Blood Cell Scale: This level analyzes the interaction at blood cell size level. It uses a Monte Carlo process. 3) Receptor Interaction Level: This level studies the interaction of blood components (specifically Angiotension II) with receptors (known as ATR1) on the heart wall. It uses a direct simulation method known as molecular dynamics. The Continuum Level - Sources and Sinks The simulation focuses on modeling flows in the left ventricle. Assuming the pulmonary and aortic valves are closed, inflow to the atrium is simulated by 8 distributed sources within the atrium. According to Peskin [4], the continuity equation can be written as: V11 == cp(r,t) == Q(t)cpo (r) == 0 ---- (1) This is in order to have the source strength determined at any instant by the volumetric rate of flow, Q (t). From (1) dV dr - = Q(t)cp 0 (r) ---- (2) Let: 1 v = Q(t) => dV =- Q(t)2 => CPo (r) =- 2rcr 2 2Jr.r dr. 2rcr ---- (3) Hence, the configuration ofthe sources can be expressed as: qJ o 1 =- - - - - ---- ---- (4) 2Jr.((x-x a)2 +(y_ Ya)2) where (xa,ya) is a point in the middle of the atrium. Also, since the domain is periodic, JV .v J rp 0 (r) dv o ---- (5) Thus, a sink is needed corresponding to the atrial source (conservation of mass). Using two non-negative weight functions with integral 1: ---- (6) Wa and We represent the source and sink functions respectively. 9 It should be noted that since all modeling is in 2-D, we have to convert areas to volumes of the cardiac chamber. Peskin and Printz suggest multiplying the area obtained with a characteristic depth of 1.84cm (Peskin and Printz [5] -pg 40). Q (t) used in the above equations has dimensions (cm2/s). From (3): Vet) = Q(t) => Q(t) =2m-V(t) 21r.r ---- (7) Figures (4) and (5) below are the 2D volumetric flow rates across the mitral valve for a female (Patient 1) and male patient (Patient 2) aged 39 and 72 respectively. These were obtained from the echocardiograph showing the A and E peak (See Figures 1 in Appendices A and B). In Figure 4, the E peak is higher than the A peak. This is normal and signifies a healthy functioning heart. The first peak shows passive filling of the ventricle and it takes up about 60 % of the total diastolic time. The small atrial contraction (Peak E) is necessary to totally empty the atrium. This takes up the remaining 40% ofthe total diastolic time. 10 Patient 1: 2- D Volumetric Flow Across Mitral Valve vs % Total Diastolic Time 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 ~ . •• • • • • • •• • • A • • ••• 200 ~ • •• .t., • • • • O.------r------,----r------.-----.... ~ ~ ~ a • E • 20 40 60 100 80 % Total Diastolic Time Figure 4: Patient 1 A and E peak information showing variation of 2-D volumetric flow rate across mitral valve with % Total Diastolic Time Patient 2: 2 - D Volumetric Flow Across Mitral Valve vs % Total Diastolic Time E en e () Q) ~ 1000 E ~ ~ ~ 600 Q) 400 E :::l o > •• 800 2>:0 () :::l _() .-L.. "l 200 • • •• •• ..• E·· •• •• •• •• A ••• • • •• •• • •• O-.--------r------,------.------,----~ o 20 40 60 80 % Total Diastolic Time Figure 5: Patient 2 A and E peak information showing variation of2Dvolumetric flow rate across mitral valve with % total Diastolic time 11 100 Figure (5) has an opposite peak height configuration. The A (second) peak is higher than the first, and takes up about 60% of the total diastolic time. This suggests that the ventricle is less able to relax. The cardiac muscles have enlarged through thickening and shortening of its fibers due to increased resistance in circulation. This is a hypertrophied heart. The large A peak signifies strong and prolonged atrial contraction as it tries to empty its content into the stiff ventricle. The Continuum Level - Modeling the Flow The Navier Stokes equations defined on an x-y Cartesian co-ordinate system are: J p ( au at + U"• V U" + vP = It V 2u" ~ ft (8) where it is the velocity vector, p is the density, t is the time, p is the pressure and viscosity is f.l. ft is the boundary force arising from the heart muscles. It is defined from Peskin [5] as: ft(x,t) =J](s,t }5(x - X(s,t )~s o ---- (9) J is the boundary element force at the point s defined on a Lagrangian system and x is defined on the Cartesian system. X" is the nth point on the Lagrangian system. The delta functions are defined as: ---- (10) 12 ~ _I (1 +cos 1lX )Ixl 2h} 0" () x = 4h 2h { o Ixl ~ 2h ---- (11) These can be rewritten as: 2 l\(r) 3-21 rl-h!1+41 rl-41 r 8 1 , 1 for Ir I~ 2 rl~~ X r=- h ---- (12) ---- (14) Implementation of the above equations employs a finite difference method using three correction steps for the time advance of velocity. The boundary points X are advanced according to the relation [7]: i n+1(s) = in (s) + MLU n+1(x)o" (x - in (s))h 2 x ---- (14) The numerical method is fully detailed in Peskin and Printz [5], Peskin [4], Macpherson and Neti [3], [7]. With the aid of software, the co-ordinates for the shape of the left ventricle and atrium at various times in diastole are obtained. This data is differentiated with respect to time to obtain the velocities at each point as a function of time, ensuring that the correct ventricular shape variation is obtained. The blood flow velocity closest to the membrane is used as the bulk flow input to the blood flow scale calculation. Note that the mitral valve is excluded because of disturbances it causes in the flow profile of the present model. 13 Chapter 5 Results and Discussion Patient 1 Analysis Patient 1 is a 39yr old female. As shown in figure 6, the E to A height ratio is about 1.72. Passive filling of the atrium takes about 60% of the total diastolic time and involves high velocities. Correspondingly, ventricular volume increases rapidly initially to accommodate this as shown in Figure 7. Atrial contraction time is 40% of the diastolic time and is slow. The ventricular outward movement is slow towards the end. Patient 1: Flow Velocity vs %Time 100"T ~ .----------------------, 90 E 80 ~. 70 ~ •• • • • rJ)..-- 60 co ~ 40 'g 30 ~ 20 ~ 10 ~ \ 0 .--------,------,,------,--------,----~ ~ ~ 0 t3 E 5 ~~ ~ IT: • • • • o 20 • • • • • • • •• ••• •• •• • • 60 40 % Time Figure 6: Patient 1 A& E peak information 14 80 100 Figure 7: Patient 1 - Schematic diagram showing left atrial and ventricular movement Table 1: Patient 1 ventricular volume for beginning and end diastole Patient 1 Area (em.!) First Frame 16.14 29.70 Last Frame 39.93 71.93 15 Volume (cm j ) Table 1 shows blood ventricular volume from beginning to end diastole. This is obtained by multiplying the ventricular area by a depth of 1.84 cm as suggested in Peskin and Printz[7]. The volume increases by a factor of about 2. Patient 1 Simulation Output at Different Time Steps (a) (b) Figure 8: Blood flow in left ventricle after time steps (a) 2 and (b) 50 16 (d) (c) Figure 9: Blood flow in left ventricle after time steps (c)150 and (d)350 Figures 8 and 9 show advancing flows in the ventricle. The frames show the flow velocity increasing with time in the ventricle (from (a) to (d». Assuming that diastolic filling takes about 0.5s, we used a time step of 5 E- 4 in our calculation (thus 1000 times steps are needed to complete the simulation). Obtaining the correct and complete simulation entails trail and error and experience. Currently, reasonably flows have being obtained only to about the 400 th time step, after which the flows become turbulent. This is because once the pressure difference between the atrium and ventricle is not high enough, there is insufficient driving force and the velocity vectors start changing direction rapidly and the flows become turbulent. 17 Figure 9-(d) above shows the flows arising at 350th time step (0.175s). The blood velocity across the mitral valve is about 26cm/s. The highest normal velocities are those vectors directed towards the bottom of the ventricle as shown by the arrow. These are flowing at about 3.lcm/s. Patient 2 Analysis Patient 2 is a 72 yr old man. The E to A peak ratio (0.44) is very low. The percentage of the total diastolic time occupied by the first peak is also low (about 40% instead ofthe healthy 66% time). The remaining time is occupied by the A-peak since strong prolonged atrial contraction is needed to totally eject blood from the atrium. The ventricle initially gradually moves outward. During atrial contraction, the outward movement is more sudden Patient 2: Flow Velocity vs % Time 100 + - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - , 90 ~~ en_ en en 0 __ 5(IJ UE ~'Q;' .> u_ o (IJ > > Q) ~ u:: 80 • 70 ~~ 60 ~~ 50 •• • •• ~~ 40 30 201 10 ••• • • • • • ••• •• • • • • • • • •• •• .... O..--------r----,------,------r----.,.. o 20 40 60 80 100 % Time Figure 10: Patient 2 A& E peak information 18 Figure 11: Patient 2- Schematic diagram showing atrial and ventricular movement Table 2 shows blood ventricular volume from beginning to end diastole. Table 2: Patient 2 ventricular volume for beginning and end diastole Patient 2 Area (cm l ) Volume (em:';) First Frame 19.52 35.92 Last Frame 34.29 63.09 19 Patient 2 Simulation Output at Different Time Steps (~ (b) Figure 12: Blood flow in left ventricle...after time steps (a) 2 and (b)100 ..,. '. ,; (d) (e) Figure 13: Blood flow in left ventricle after time steps (c) 200, (d) 300 and (e) 400 (c) 20 Figures 12 and 13 above are the flow patterns for Patient 2 for 400 time steps. At this time, the velocity across the mitral valve is about 26.2 cm/s. Again, the arrow shows the direction of the highest normal velocities to the ventricular membrane. It is about 1.72cm/s for this patient. Although the full simulation for both patients is yet to be done, both profiles suggest that the lower part of the ventricle away from the septum could be the site with absorbs most Angiotensin II and could be the potential site for the initiation of hypertrophy. 21 Chapter 6 Direction of Research Weare working to improve the simulation and hope to publish extensive results soon. This means developing more code to mechanize the process as much as possible. This will be a powerful tool for clinical and health industry because it will enable measurements of the effects of specific loads (such as different drug dosages) on hemodynamic properties in the heart. This will greatly improve drug development. Also, we hope to be able to extend this research to flows in other organs of the body. 22 Appendix A - Patient 1 0:06:57 li3 H -71b 10 m/s Figure 1: A and E Peak Echocardiograph Patient 1 Diastole Cycle Figure 2: Frame 1 23 Figure 3: Frame 2 Figure 4: Frame 3 24 Figure 5 : Frame 4 Figure 6 : Frame 5 25 Appendix B- Patient 2 ~ ~~ J7l4- ~ "" w , ... 1B'M1U: :tm:~ ' DM.i~ :~;t=. ~ . , ~-'l""3I~.. w ." ;~. &1 oiRl.-..:" .3 -~.......- - - - " n:ij'i~1 1= r ~. ......... 1·: .. ~ ;\~;':~ ..... ;, .. ~ .. " ~ --m Figure 1: Patient 2 A& E peak echocardiograph ;!!!~.~v~~ ~2: ~:s: ~~ ::!D'~ na!l'e;iiGb -m 26 INTENTIONAL SI;COND EXPOSURE Appendix B- Patient 2 ~~~',:':~: ~-~J.i it.:.',,' _~ti: 7=-,,11""",: .... ~j,~~.;::';':::. -;-s;;~ 'i:':S_:," ;:'=,?" ~=;~1 '-~S:.::""fIt ::~"':: ,_ W".::::. ,. . -~ ~ -r--. '::fl"~._ ..:.:~.Z; =""iI:;;'~;: ==_~ :::'-.=... JI.":: .~~, ~~'I= :::.:r ;:;".,.~ r'~'F';':~= -all; :?=;;- =~'~1 :f;:'~ -~~~ _ ;P:~':~-:':: 4~---".--- Figure 1: Patient 2 A& E peak echocardiograph . ~_-:~ "",,-::'.' ~~-2 ,JL_/::':!f-~~:.:I. -~~-~ -; ~:=~;.:: I .: ='~.~ L.::~ ~;-:"::-~-:-,>.?:,.e~ =~ ~e:~-~~ '~ .... '--.' ' .--~-,-;: -~----;- M§§§-- ~"'--''-","-, ..""",''--~~~~''--------='-~~"'~-'''':''-::....-.'-' .~ .'- .. =-F-~ 26 Figure 2: M-mode tracing at left ventricular papillary muscle level Figure 18 above is patient 2's m-mode tracing at the left ventricular papillary muscle level. It shows the change in length from the shortest length (cm) with time (sec) based on the echo data ofm-modes, mitral size and ventricle size. The change in width of the ventricle at the papillary muscle is 4.5 cm to 6.5cm. The septum moves quite a bit too. Diastole Cycle , --"lIi..'--Figure 3: Frame 1 27 Figure 4: Frame 2 Figure 5: Frame 3 28 Figure 6 : Frame 4 Figure 7 : Frame 5 29 Bibliography [1] Otto Catherine M. and Pearlman Alan S. Textbook of Clinical Echocardiography [2] Caro CG, Pedley TJ, Schroter RC and Seed WA The mechanics ofcirculation (Oxford University Press),pp.209 1978. [3] Macpherson AK and Neti S 2001 A rapid procedure for initial drug evaluation, Phys. In Med. And BioI. 46,pp 6-, 2001 [4] Peskin CS,1977 Numerical Analysis of Blood Flow in the Heart,J. Compo Phys 25,pp.220-252, 1977 [5] Peskin CS and Printz BF, Improved Volume Conservation in the Computation of Flows with Immersed Elastic Boundaries J.Comp. Phys 105, pp.33-46, 1993. [6] Hoppensteadt, Frank, C. and Peskin, Charles S. Modeling and Simulation in Medicine and the Life Sciences (2nd Edition). [7] Macpherson AK and Neti S 2001 Effect of Angiotensin II on heart blood flow and hypertension, 2002. [8] Milnor, William R. Cardiovascular Physiology 1990 30 Vita I am the first of five children of Joseph and Kwansima Bedu-Amissah born on the 30 th ofDecember, 1978 in Takoradi, Ghana (West Africa). Six years ago, I opted to attend college in the States over my native Ghana. I enrolled at Knox College (Galesburg - Illinois) for a 3 semesters before transferring to Iowa State University (Ames, Iowa) to finish my bachelor's degree. In May 2001, I received a B.Sc in Chemical Engineering. In the fall ofthe same year, I enrolled in Lehigh University's graduate program in Chemical Engineering. 31 ENDOF TITLE