* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Trees of the CSRA Eco-Meet 2016 Study Packet

Survey

Document related concepts

Plant physiology wikipedia , lookup

Evolutionary history of plants wikipedia , lookup

Plant morphology wikipedia , lookup

Ornamental bulbous plant wikipedia , lookup

Plant ecology wikipedia , lookup

Plant evolutionary developmental biology wikipedia , lookup

Plant reproduction wikipedia , lookup

Flowering plant wikipedia , lookup

Pinus strobus wikipedia , lookup

Glossary of plant morphology wikipedia , lookup

Tree shaping wikipedia , lookup

Perovskia atriplicifolia wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

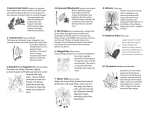

Trees of the CSRA Eco-Meet 2016 Study Packet Georgia State Standards Met S7CS10. Students will enhance reading in all curriculum areas by Building vocabulary knowledge. S7L1. Students will investigate the diversity of living organisms and how they can be compared scientifically. South Carolina State Standards Met 6-1.3 Classify organisms, objects, and materials according to their physical characteristics by using a dichotomous key 6-2.2 Recognize the hierarchical structure of the classification (taxonomy) of organisms (including the seven major levels or categories of living things—namely, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species). 6-2.3 Compare the characteristic structures of various groups of plants (including vascular or nonvascular, seed or spore-producing, flowering or cone-bearing, and monocot or dicot). 6-2.7 Summarize the processes required for plant survival (including photosynthesis, respiration, and transpiration). 7-2.4 Explain how cellular processes (including respiration, photosynthesis in plants, mitosis, and waste elimination) are essential to the survival of the organism. Trees are living organisms that are a part of the plant kingdom. There are many different types of trees in the CSRA, and this packet is designed to help you learn about the native trees of the area and provide you with the knowledge necessary to identify trees in the wild, or in your neighborhood, on your own. As a part of your Eco-Meet test, you will be provided with a copy of the 1998 edition of A Field Guide to Eastern Trees: Eastern United States and Canada, Including the Midwest by George A. Petrides, which is a part of the Peterson Field Guide Series. You will be asked to use the field guide to identify a number of trees based on images and examples of various features of the trees. The rest of the test will consist of questions drawn from the study packet. The Life of a Tree There are seven stages in a tree’s life: Seed – Sprout – Seedling – Sapling – Mature – Decline – Snag 1 Seeds The outer layer of the seed is called the seed coat. Inside the seed coat one can find the embryo and food that will support its growth. The embryo is made up of one or more cotelydons, which will become the first leaves of the plant; the radicle, which will form roots; and the plumule, which will form the shoot once the seed germinates and the embryo begins to grow and breaks free of the seed coat. While all seeds are made up of an embryo, food source, and seed coat, seeds come in a variety of shapes, colors, and sizes. Some seeds are found in fruit. Trees that house their seeds within fruit are known as angiosperms. Most people are familiar with fruits like apples and oranges that have seeds inside, but many do not realize that acorns and the outer shell of sunflower seeds are also fruits. 2 So what is the deal with fruit? Flowering trees produce fruit, and fruit actually comes from the flower. Flowers and fruit are a part of the flowering plant’s reproductive cycle. Flowers vary from plant to plant, and some plants have both male and female structures within a single flower, while other plants have separate male and female flowers growing on the same plant, and yet other varieties produce entirely separate male and female plants. The male structures of flowers are called the stamen and produce pollen. The female structures form the pistil (or carpel) and include the stigma, style, ovary, and ovules. 3 A flower is pollinated when pollen from the stamen finds its way to the stigma, is carried to the ovary through the style by a pollen tube, and successfully fertilizes the ovules. Pollen can be transferred to the stigma in a number of ways: by bees, other insects and animals, the wind, and even humans. Flowers vary from tree to tree and plant to plant. The diagram above shows a basic flower form, but some trees have flowers that look much different and may not contain each of the structures included in the diagram. These flowers are considered incomplete. 4 Catkins – Flowers of Oaks and Willows 5 Male catkins and female flowers of Black Oak After pollination the flower goes through a transformation. The recognizable parts of the flower, like the petals, wither. The ovary grows and becomes fruit, while the ovules inside of it develop into seeds. Angiosperms and Fruits Angiosperms house their seeds in fruits. When most people think of fruit they think about the fruits that humans eat, but there are many different types of fruit and not all of them are edible. There are two major categories of fruit: fleshy fruits and dry fruits. Most of the fruits that people easily recognize as fruits are fleshy fruits, but not all fleshy fruits are created equal. There are several different types of fleshy fruits, including berries, drupes, pomes, and hesperidiums. Apples, oranges, bananas, and cherries are all fleshy fruits. Dry fruits also come in a variety of shapes and sizes, including samaras and nuts. Acorns, samaras or “helicopter seeds”, and “sweetgum balls” are all dry fruits. The chart below describes some common types of fruits you may encounter in attempts identify trees. The definitions and examples below are from The Seed Site. Dry Fruits Type of Fruit Samara Definition an independent dry fruit which has part of the fruit wall extended to form a wing Examples Images Maple, Ash, Elm Maple Nut a large single hardened achene Acorns, Chestnuts A – White Oak Acorn B- Red Oak Acorn Fleshy Fruits Pomes a fleshy fruit Apples, with a thin Pears skin, not formed from the ovary but from another part of the plant 6 Crabapples Fleshy Fruits Drupe a single fleshy fruit with a hard stone which contains the single seed Cherries, Peaches, Plums, Olives Cherries Berry a single fleshy fruit without a stone, usually containing a number of seeds Kiwi, Banana, Coffee, Tomato Hesperidium a berry with a tough, aromatic rind Oranges, Grapefruit, Lemons, Limes Kiwi Oranges Gymnosperms Gymnosperms are plants that produce seeds, but do not produce flowers or fruit. Because the seeds are not enclosed in fruit, they are considered naked. Common gymnosperms include pines, firs, junipers, other conifers, and gingkos. The reproductive structures of many gymnosperms are known as cones, or strobili. The rather large brown cones found on many pine trees, for example, are actually the female strobili. Attached to the top of each of the cone scales are two ovules. The ovules, once pollinated, will develop into seeds. The smaller more tightly packed cones are male and release pollen. 7 Male Loblolly Pine Cones 8 Female Loblolly Pine Cone Seed Dispersal and Suitable Environments Soil Water Air In order to grow and mature into trees, seeds must find their way to an environment where all of their needs are met. Initially, most seeds need soil, air, and the appropriate amount of water to begin the germination process and sprout. Some seeds also need Sunlight Space Temperature to be exposed to the right temperatures or amount of light before they will germinate. Seeds will lay dormant until all of their needs are met, and many are eaten, crushed, or rot before they have a chance to grow. After seeds germinate, they also require the proper amount of space to grow into a tree. Imagine if every acorn from a white oak tree germinated and sprouted directly below the tree from which they fell. Eventually, the seedlings would become too crowded and would be unable to grow to their proper height. They would compete for space above and below ground as their roots and branches grew, as well as resources like light, water, and oxygen. How do seeds, which are immobile on their own, get away from their parent tree to grow? Exploding Fruit – Some seed capsules burst open, and the force of this “explosion” tosses the seeds far enough from their parent plant to grow. Animals – There are many ways that animals can assist in the dispersal of seeds. The first is by eating the fruit. Many animals cannot properly digest seeds, and after eating fruit and moving on throughout their ecosystem, they may excrete the seeds in a more appropriate environment. Other fruits are hooked or barbed, and as an animal passes under or by a plant, the fruit, with its seeds inside, get caught in the animal’s fur or feathers and may travel with the animal for days before falling or being scratched or brushed off. Other animals, like squirrels and humans, actively take seeds and deposit them in new locations. Wind – Some fruits enable seeds to be transported by the wind. Samaras provide seeds with wings and instead of dropping straight to the ground, the seeds to stay airborne longer, fluttering and twirling farther away from their parent plant. Other fruits, known as cypsela, have feathery tufts that act like parachutes and float in the breeze, carrying seeds away. One example of a plant with cypselae is the dandelion. 9 The Sprout and Photosynthesis Once the seed has germinated and sprouted, the sprout sends roots into the ground to absorb the water, nutrients, and oxygen the tree will need to continue to grow once the food from the seed is gone. At the same time the shoot will grow and break through the surface of the soil. Once this occurs, the sprout will develop its first “true” leaves and begin to make food through a process called photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is a process that allows plants to turn water, light, and carbon dioxide into oxygen and glucose. The glucose, a simple sugar, is then converted to fuel by the plant. Photosynthesis happens in the chloroplasts of plant cells. Chloroplasts contain the pigment chlorophyll which makes leaves green. Chlorophyll also enables the process of photosynthesis. Chlorophyll absorbs energy from sunlight, and that energy enables the transfer of electrons between molecules resulting in the following chemical reaction: 6H2O + 6CO2 C6H12O6 + 6O2 six molecules of water and six molecules of carbon dioxide, using energy from sunlight, changes into one molecule of glucose and six molecules of oxygen. The hydrogen found in water transfers to carbon dioxide to form glucose and oxygen is created as a byproduct. Glucose is a simple sugar that plants are able to convert to the energy they need to continue to grow and eventually reproduce. Growth and Maturity As the sprout continues to grow it becomes taller and thicker around and starts to take on more tree like characteristics. Now a seedling, the little tree adds more leaves and its roots continue to develop and spread just below the surface of the ground. Seedlings are considered saplings once they have attained a height of approximately 4.5 feet and a diameter of 1-4 inches. Saplings cannot reproduce, but will eventually grow into mature trees that reproduce. As a tree ages, it can experience different stresses, just like humans. Not having enough access to sunlight, being planted too close to other trees and plants, disease, insects, fires, and droughts are just a few of the things that can stunt the growth of a tree or cause it to go into decline. In the final stage of its lifecycle, the standing dead tree is known as a snag. Parts of the Tree 1. Roots The roots support trees and their health in three different ways. Roots help hold the tree up and in place, Roots absorb water and nutrients from the soil that keep the tree healthy, and Roots store extra food. Roots are covered in tiny root hairs that help them absorb more water. These hairs do not last for very long and are replaced every few days. The ends of the roots are protected by a small growth called a calyptra or root cap. Some trees have roots that grow deep into the ground. The roots of other trees spread out just below the surface of the soil. The roots of some trees that grow in swamps will actually grow above the water and soil! The Bald Cypress is just one example of this phenomenon. Cypress trees have “knees:” sections of their roots that poke out above the water. Bald Cypress with knees A few trees even have aerial roots that grow out of their branches and down into the ground. These roots help to prop the tree up and provide extra nutrients. 10 2. Trunk Just like the roots, the trunk is an integral part of the structure of the tree and supports the trees growth and health in a number of ways The trunk is the backbone of the tree and bears the weight of the tree’s leaves, branches, and fruit. The bark on the trunk protects the tree from pests, weather, and fires. The trunk carries water and nutrients from the roots to the leaves and vice versa. At the center of the trunk lies the heartwood. This is the strongest part of the trunk and really is the backbone of the tree. Surrounding the heartwood is the xylem. The xylem moves the nutrients and water absorbed from the ground by the roots to the rest of the tree. On the outside of the xylem is a very small layer called the cambium. This small layer of cells actually produces the new growth for the tree in the form of new cambium, xylem, and phloem. Just below the bark next to the cambium is the phloem. The phloem takes the food (glucose) produced by the leaves to the rest of the tree. 11 3. Branches and Leaves (Crown) The branches and the leaves form the crown of the tree. Leaves produce energy (food) for the tree through photosynthesis and the branches transport the food to the rest of the tree. Different types of trees branch out in different types of ways, giving each type of tree a unique silhouette (or overall shape). Identifying Mature Trees Different types of trees have many features which are helpful in identification. These include: leaf type and arrangement, twig and bud types, bark, flower, fruit, size, and silhouette. Many people use field guides to look up the various features of trees in order to identify them. In order to use these guides successfully, however, one needs to know about some common features of trees and how they are described by botanists. You will be using A Field Guide to Eastern Trees to identify trees on your Eco-Meet test. The following discussion of leaves is based on the categorization of trees established by George A. Petrides in the field guide and will help you become more familiar with different types of leaves and the structure of the guide. Leaves Trees can be broken down into two major groups based on their leaves: Trees with needle or scalelike leaves and those with broad leaves. A. Trees with needlelike or scalelike leaves (also known as hardwoods) Scalelike Red Cedar or Juniperus virginiana Needle Virginia Pine or Pinus virginiana B. Broad-leaved trees (also known as softwoods) The Broad Leaf trees can be broken into five categories based on leaf arrangement on the tree’s twigs. The following definitions will help you distinguish between the different categories of broad leaf trees: Simple leaf – a single blade attached to a twig. Compound leaf – generally an odd number of leaflets are attached to the midrib of the leaf. This midrib is joined to the twig at the stalk. Twig – the end portion of the branch with new growth, distinguished from leaf stalks and midribs by the presence of buds and in winter months, bundle scars and leaf scars, left after leaves have fallen or been removed. 12 Black Walnut or Juglans nigra L. Leaf scars indicate the location where leaf stalks were once attached to the twig, and bundle scars mark the entry points of veins into the twig. When a single leaf scar contains more than three bundle scars, this can indicate that the leaf was compound, although this is not always the case. B. Broad-leaved trees (also known as softwoods) Contd. 1. Trees with opposite compound leaves- compound leaves directly across from another on the twig 13 White Ash or Fraxinus americana 2. Trees with opposite simple leaves- leaves directly across from another on the twig 14 Red Maple or Acer Rubrum 3. Trees with alternate compound leaves – compound leaves arranged at varying points, but not directly across from each other on the twig Shagbark Hickory or Carya alba 4. Trees with alternate simple leaves – simple leaves arranged at varying points, but not directly across from each other on the twig 15 Sweetgum or Liquidambar styraciflua 5. Trees with parallel-veined leaves 16 Dwarf Palmetto or Sabal minor Trees can also be identified by looking at leaf shapes, margins, and veins. The following charts provide a glimpse of the variety of leaves found in nature. Students do not need to memorize each of these forms for the test, but should be able to identify the terms leaf shape, leaf margin, venation, dentate, serrate, and entire. They should understand how these differences can aide in identification. 17 The edge of the leaf is called the margin. This chart provides the scientific terms for various types of margins. 18 The veins on a leaf can also distinguish it from leaves of other similar trees. Venation is a term to used to describe the different patterns in the veins of different types of leaves. Below is a chart that provides visual comparison of the different types of veins. 19 Buds, Bundle Scars, and Leaf Scars During winter months when leaves are generally absent from broadleaf trees, buds, bundle scars, and leaf scars can be used to aide in tree identification. Careful inspection of the location of leaf scars can indicate whether the leaves are opposite or alternate, and the number of bundle scars may indicate whether or not the leaves in question are compound or simple. Leaf scars indicate the location where leaf stalks were once attached to the twig, and bundle scars mark the entry points of veins into the twig. When a single leaf scar contains more than three bundle scars, this can indicate that the leaf was compound, although this is not always the case. Buds also vary from tree to tree, and the number of scales, color, and size can aide in identification. Bark During winter months, bark can be very helpful when it comes to identifying trees. Below are some examples of bark features that can be found in trees common to the CSRA. Type Color Name Type Color Name Smooth Light Grey American Holly Fibrous Red Cedar Deeply Grooved/Furrowed Dark Grey Black Walnut Warty Medium Grey Hackberry Shaggy/Peeling Red-brown/Orange/Black New River Birch Scaly Blackish/Dark Orange Loblolly Pine Geographical Regions and the Types of Trees found in the CSRA Based on physical geography, the CSRA is located on the border of two different regions, the Piedmont and the Upper Coastal Plain. The Fall Line separates these two regions, and while some trees can grow in both regions, there are many that do not. According to The University of Georgia Museum of Natural History, the Piedmont region, located north of the Fall Line, includes “oaks, hickories, Short-leaf Pine, and Loblolly Pine. Pines occur in the less favorable or disturbed areas of the Piedmont. In river valleys, mixed deciduous forests of hardwood trees such as Sweet Gum, Beech, Red Maple, elms, and birches are found.” In contrast, the diversity of the Coastal Plain, located south of the Fall Line, lends itself as a home to a number of different trees: “On well-drained soils of the Coastal Plain, the dominant plant species are Long-leaf Pine, Loblolly Pine, and several species of oak. On poorly drained soils, the dominant species are Long-leaf Pine and Slash Pine with a dense ground cover of Saw Palmetto, Gallberry, and Wiregrass. These plants are adapted to a humid subtropical climate of mild winters, hot summers, high rainfall, and frequent ground fires. Where the soil is poorly drained, Pond Pines are dominate. The Southern Mixed Hardwood community includes oaks, Sweet Gum, magnolias, Red Bay, and Pignut Hickory. Such hardwood communities are found bordering freshwater streams and floodplain swamps and in low, fertile areas near the coast. Wooded swamps composed of Cypress, Tupelo, and Red Maple trees are found adjacent to swamps, ponds, and lakes as well as along sluggish, meandering streams.” Different types of trees have different needs with regards to the amount of water, sunlight, and type of soil in which they can grow. These factors determine the suitability of different regions for their growth and well being and can aide you in determining whether or not to plant a certain species in your back yard or garden. Many types of trees can grow in Georgia and South Carolina, but not all of the trees you see as you drive down the highway or walk through the woods grow in our area naturally. Many of these trees were brought into the area from oversees or other parts of the country. Trees that have always grown in this part of the country and were not introduced by people from other regions or countries are called native trees. Below is a list of native trees, their common names, and scientific names. Students do not need to memorize this list, but being familiar with these trees will help the students with identification on the test using their field guide. Students should understand the difference between common names and scientific names, but do not need to memorize each tree and its names. Native Trees Common Name American Beech American Holly American Hornbeam American Yellowwood Bald Cypress Big-Leaf Magnolia Black Gum or Tupelo Black Walnut Carolina Buckthorn Carolina Silverbell Chestnut Oak Downy Serviceberry Eastern Hemlock Eastern Redbud Eastern Red Cedar Florida or Southern Sugar Maple Flowering Dogwood Fringetree of Grancy-Greybeard Green Ash Laurel Oak Live Oak Loblolly Bay Loblolly Pine Longleaf Pine Mayhaw Mockernut Hickory Northern Red Oak Palmetto Palm or Cabbage Palm Parsley Hawthorn Pignut Hickory Possumhaw Post Oak Red Maple River Birch Scarlet Oak Shagbark Hickory Shortleaf Pine Shumard Oak Slash Pine Southern Magnolia Southern Red Oak Genus Species Fagus grandifolia Ilex opaca Carpinus caroliniana Cladrastis kentukea Taxodium distichum Magnolia macrophylia Nyssa sylvatica Juglans nigra Frangula caroliniana Halesia tetraptera Quercus prinus Amelanchier arborea Tsuga canadensis Cercis canadensis Juniperus virginiana Acer barbatum Cornus florida Chionanthus viginicus Fraxinus pennsylvanica Quercus hemisphaerica Quercus virginiana Gordonia Iasianthus Pinus taeda Pinus palustris Crataegus aestivalis Carya tomentosa Quercus rubra Sabal palmetto Crataegus marshallii Carya glabra Ilex dcidua Quercus stellata Acer rebrum Betula nigra Quercus coccinea Carya ovata Pinus echinata Quercus shumardii Pinus elliottii Magnolia grandiflora Quercus falcata Family (Common/Scientific) Beech/Fagaceae Holly/Aquifoliaceae Birch/Betulaceae Pea/Fabaceae Redwood/Taxodiaceae Magnolia/Magnoliaceae Nyssa/Nyssaceae Walnut/Juglandaceae Buckthorn/Rhamnceae Storax/Styracaceae Beech/Fagaceae Rose/Rosaceae Pine/Pinaceae Legume/Fabaceae Juniper/Cupressaceae Maple/Aceraceae Dogwood/Cornaceae Olive/Oleaceae Olive/Oleaceae Beech/Fagaceae Beech/Fagaceae Tea/Theaceae Pine/Pinaceae Pine/Pinaceae Rose/Rosaceae Walnut/Juglandaceae Beech/Fagaceae Palm/Palmaceae Rose/Rosaceae Walnut/Juglandaceae Holly/Aquifoliaceae Beech/Fagaceae Maple/Aceraceae Birch/Betulaceae Beech/Fagaceae Walnut/Juglandaceae Pine/Pinaceae Beech/Fagaceae Pine/Pinaceae Magnolia/Magnoliaceae Beech/Fagaceae Spruce Pine Sugar Maple Sugarberry Swamp Chestnut Oak or Basket Oak Sweetgum Sycamore Tulip Poplar or Yellow Poplar Two-Winged Silverbell Virginia Pine Washington Hawthorn Water Oak Willow Oak White Ash White Oak White Pine Yaupon Holly Yellow Buckeye Pinus glabra Acer saccharum Celtis laevigata Quercus michauxil Liquidambar styraciflua Platanus occidentalis Liriodendron tulipifera Halesia diptera Pinus virginiana Crataegus phaenopyrum Quercus nigra Quercus phellos Fraxinus americana Quercus alba Pinus strobus Ilex vomitoria Aesculus flava Pine/Pinaceae Maple/Aceraceae Elm/Ulmaceae Beech/Fagaceae Witchhazel/Hamamelidaceae Sycamore/Platanaceae Magnolia/Magnoliaceae Storax/Styracaceae Pine/Pinaceae Rose/Rosaceae Beech/Fagaceae Beech/Fagaceae Olive/Oleaceae Beech/Fagaceae Pine/Pinaceae Holly/Aquifoliaceae Buckeye/Hippocastanaceae Invasive Trees The trees on the list above all grow naturally in our area and other parts of the United States. There are, however, trees and other plants that have been imported from other parts of the country and all over the world in our area. Some of these imports are harmless, but occasionally importing trees and plants can have a negative impact on both the environment and the human community. When this happens these plants become known as invasive species. According to the Georgia Forestry Commission, “An invasive species is any species (including its seeds, eggs, spores, or other biological material capable of propagation) that is not native to a given ecosystem; and whose presence causes economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.” The threats that these plants pose vary. Many displace native species and negatively impact the ecosystem. Mimosas, for example, once well established, create a dense canopy that can block out sunlight and inhibit the growth of other plants that animals and insects may rely on for food or shelter. The Tallow Tree displaces native plants and can also change the chemical composition of the soil where it grows because of the tannins it releases. The Tree of Heaven, or Chinese Sumac, and Chinaberry Trees also take over areas and push native species out of their natural habitats. Both trees release chemicals that act as herbicides and help them establish dominance over native plants. Chinaberry Trees are poisonous to humans and some other mammals, and the Tree of Heaven can also wreak havoc in populated areas by disturbing pavement, sidewalks, and other structures underground. Invasive Trees Common Name Tallow Tree Tree of Heaven China Berry Tree Princess Tree Mimosa Genus Species Triadica sebifera Ailanthus altissima Melia azedarach Paulownia tomentosa Albizia julibtissin Classification In the 1700s a scientist named Carl von Linne, professionally known as Carolus Linnaeus, developed a system for organizing living beings based on their common features. Linnaeus’ system placed specific types of living things into ever broadening categories with other organisms based on a number of shared characteristics or traits. The system is described as follows by professor Michael McDarby, “Each particular type of living thing would be designated a species (from the same root word as "specific"). Closely-related species could be collected within a larger grouping, a genus; related genera are grouped into a family, families into an order, orders into a class, classes into a phylum, and phyla into a Kingdom, the biggest and most general group.” During the 1700s, writing in Latin was the preferred method for scientists, and Latin classification terminology is still in use today. As an example, below is a chart outlining the classification of Live Oak trees from the United States Department of Agriculture. Please note that some use the term division instead of phylum. Kingdom Subkingdom Superdivision Division Class Subclass Order Family Genus Species Plantae – Plants Tracheobionta – Vascular plants Spermatophyta – Seed plants Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons Hamamelididae Fagales Fagaceae – Beech family Quercus L. – oak Quercus virginiana Mill. – live oak 20 Trees and other living things will often be referred to in academic texts and field guides by both their common name and Latin genus and species. Because common names can vary in different regions and communities, using and being able to recognize scientific names can limit confusion. For our purposes, students should be able to recognize the differences between scientific and common names, explain the scientific classification system, and locate scientific and common names in field guides. They do not need to memorize the scientific names of any trees. Sample Questions: Which of the following are types of fruit: Fill in the blanks: a) b) c) d) Pomes Strobili Drupes Stigma Using the Peterson Field Guide provide the genus and species of the tree pictured: ____________ __________ 21 Bibliography Armstrong, W.P. “Identification of Major Types of Fruit.” Wayne’s Word: An Online Textbook of Natural History. http://waynesword.palomar.edu/fruitid1.htm (accessed December 21, 2012). “Bundle scar.” The Free Dictionary. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/bundle+scar (accessed January 7, 2013). Conrad, Jim. “Oak Flowers.” The Backyard Nature Website. http://www.backyardnature.net/fl_bloak.htm (accessed January 8, 2013). Enchanted Learning.“Flower Anatomy.” Enchantedlearning.com. http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/plants/printouts/floweranatomy.shtml (accessed December 28, 2012). Evans, C.W., C. T. Bargeron, D.J. Moorhead, and G. K. Douce, The Bugwood Network, The University of Georgia. Invasive Plants of Georgia’s Forests: Identification and Control… Georgia Forestry Commission, University of Georgia, and USDA Forest Service, 2006. http://www.gainvasives.org/pubs/gfcnew.pdf (accessed December 20, 2012). Farabee, M.J. “Flowering Plant Reproduction: Fertilization and Fruits.” Online Biology Book. http://www.emc.maricopa.edu/faculty/farabee/biobk/biobookflowersii.html#Fruit (accessed December 28, 2012). Farabee, M.J. “Photosynthesis: What is Photosynthesis?” Online Biology Book. http://www.emc.maricopa.edu/faculty/farabee/biobk/biobookps.html (accessed December 21, 2012). “Fruit.” The 1911 Classic Encyclopedia. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Fruit (accessed December 28, 2012). “Fruits.” The Seed Site. http://theseedsite.co.uk/fruits.html (accessed January 7, 2013); Julivert, Maria Angeles. Trees. Field Guide Series. New York: Enchanted Lion Books, 2006. Koning, Ross E. 1994. “Fruit Growth and Types.” Plant Physiology Information Website. http://plantphys.info/plants_human/fruittype.shtml. (accessed December 28, 2012). Landau, Fred. “Gymnosperms.” Gymnosperms. http://faculty.unlv.edu/landau/gymnosperms.htm (accessed January 5, 2013). MacDonald, Greg, Brent Sellers, Ken Langeland, Tina Duperron-Bond, and Eileen Ketterer-Guest. “Albizia julibrissin.” Florida Invasive Plant Education Initiative in the Parks. Excerpt from the University of Florida, IFAS Extension, Circular 1529, Invasive Species Management Plans for Florida, 2008. http://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/parks/mimosa.html (accessed January 2, 2013). McDarby, Michael. “Explaining Life: Classification.” An Online Introducation to Advanced Biology. http://faculty.fmcc.suny.edu/mcdarby/majors101book/Chapter_02-A_Bit_of_History/02-Explaining-Life-Classification.htm (accessed January 7, 2012). Michel, Carol. May Dreams Gardens. http://www.maydreamsgardens.com/2008/09/drupes-pods-and-pomes.html (accessed December 21, 2012). National Invasive Species Information Center. “Tree-of-Heaven.” United States Department of Agriculture National Agriculture Library. http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/plants/treeheaven.shtml#.UORRuuTBG8A (accessed January 2, 2013). Petrides, George A. A Field Guide to Eastern Trees: Eastern United States and Canada, Including the Midwest. The Peterson Field Guide Series. Ill. by Janet Wehr. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1988. Pevzner. “Photosynthesis and Respiration.” https://sites.google.com/site/gradeeightscience/september/photosynthesis-and-respiration (accessed 12/21/12). Reemts, Charlotte. “Chinaberry.” Plant Conservation Alliance’s Alien Plant Working Group Least Wanted. http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/fact/meaz1.htm (accessed January 2, 2013). Shakhashiri, Bassam Z. “Chlorophyll.” Chemical of the Week. http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/chemweek/chlrphyl/chlrphyl.html (aaccessed December 21, 2012). Stack, Greg, Ron Wolford, Jane Scherer, and Marsha Hawley. “Is it Dust, Dirt, Dandruff, or a Seed.” The Great Plant Escape. http://urbanext.illinois.edu/gpe/case3/c3facts3.html (accessed January 2, 2013). Swearingen, J., B. Slattery, K. Reshetiloff, and S. Zwicker. “Tree of Heaven.” Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas: Revised & Updated with More Species and Expanded Control Guidance. Excerpt from National Parks Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas, 4th ed. 2010. http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/pubs/midatlantic/aial.htm (accessed January 2, 2013). Texas A & M Forest Service. “How Trees Grow.” Trees of Texas. http://texastreeid.tamu.edu/content/howTreesGrow/#lifecycle (accessed December 18,2012). Trees Charlotte. “How a Tree Works!” http://treescharlotte.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/How-A-Tree-Works.pdf (accessed (December 21, 2015). Project Learning Tree. “Tree Factory.” https://www.plt.org/family-activities-tree-factory (accessed (December 21, 2015). United States Department of Agriculture National Resources Conservation Service. “Quercus virginiana Mill.” Plants Database. http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=QUVI&photoID=quvi_003_avp.jpg (accessed January 7, 2012). The University of Georgia Museum of Natural History. “Physiographical Regions of Georgia.” Georgia Wildlife Web. http://naturalhistory.uga.edu/~gmnh/gawildlife/index.php?page=information/regions (accessed January 7, 2012). Wade, Gary, Elaine Nash, Ed McDowell, Brenda Beckham, and Sharlys Crisafulli. “Native Plants of Georgia Part1: Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines.” The University of Georgia College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences. Excerpt from Wade, Gary, Elaine Nash, Ed McDowell, Brenda Beckham, and Sharlys Crisafulli, The University of Georgia Cooperative Extension, Colleges of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences & Family and Consumer Sciences, Native Plants of Georgia, Bulletin 987, 2011. http://www.caes.uga.edu/Publications/pubDetail.cfm?pk_id=7763#Ecology (accessed December 20, 2012). Photography Credits 1 Edited version of image Tree Life Cycle By jehsomwang - iStock - Getty Images via GPB. Edited version of image By KDS444 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 3 By Mariana Ruiz LadyofHats (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons 4 Evelyn Simak [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 5 Conrad, Jim. Last updated Sun Dec 11 2011 12:40:01 GMT-0500 (Eastern Standard Time) . Page title: Oak Flowers. Retrieved from The Backyard Nature Website at http://www.backyardnature.net/fl_bloak.htm. 6 By Carol Michel, “Drupes, Pods, and Pomes,” May Dreams Gardens, http://www.maydreamsgardens.com/2008/09/drupes-podsand-pomes.html (accessed December 21, 2012), used with permission. 7 Image taken by en:User:Pollinator, released under GFDL 19:45, Oct 20, 2004 (UTC) 8 By Alicia Pimental from Queenstown, Maryland, United States (DSC_6552) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 9 By Alex Valavanis (Flickr) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 10 By Randy Robertson from Newbury Park, California, USA (Branching Down) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 11 Modified from image by Project Learning Tree (https://www.plt.org/family-activities-tree-factory) 12 By Susan Sweeney [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 13 By Pedro Paramo (Pedro paramo) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 14 By Bmerva (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 15 By Bmerva (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons 16 By Carey Minteer, University of Georgia, United States [CC-BY-3.0-us (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons 17 By User Debivort (La bildo estas kopiita de wikipedia:en.) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons 18 By User Debivort (La bildo estas kopiita de wikipedia:en.) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons 19 By User Debivort (La bildo estas kopiita de wikipedia:en.) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons 20 National Resources Conservation Service, “Quercus virginiana Mill.,” United States Department of Agriculture, http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=QUVI&photoID=quvi_003_avp.jpg (accessed January 7, 2012). 21 By Thisisbossi (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons 2