* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Building Materials by Packing Spheres

Industrial applications of nanotechnology wikipedia , lookup

X-ray crystallography wikipedia , lookup

Ultrahydrophobicity wikipedia , lookup

Density of states wikipedia , lookup

Quasicrystal wikipedia , lookup

Low-energy electron diffraction wikipedia , lookup

Acoustic metamaterial wikipedia , lookup

History of metamaterials wikipedia , lookup

Geometrical frustration wikipedia , lookup

Nanochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Mineral processing wikipedia , lookup

Freeze-casting wikipedia , lookup

Crystal structure wikipedia , lookup

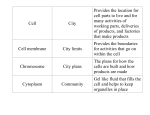

www.mrs.org/publications/bulletin Building Materials by Packing Spheres Vinothan N. Manoharan and David J. Pine Abstract An effective way to build ordered materials with micrometer- or submicrometer-sized features is to pack together monodisperse (equal-sized) colloidal particles. But most monodisperse particles in this size range are spheres, and thus one problem in building new micrometer-scale ordered materials is controlling how spheres pack. In this article, we discuss how this problem can be approached by constructing and studying packings in the few-sphere limit. Confinement of particles within containers such as micropatterned holes or spherical droplets can lead to some unexpected and diverse types of polyhedra that may become building blocks for more complex materials. The packing processes that form these polyhedra may also be a source of disorder in dense bulk suspensions. Keywords: colloids, microspheres, optical materials, packing, structure. Introduction Monodisperse colloidal particles are natural building blocks for composite materials with micrometer-scale features, but these particles have one inherent limitation: they are nearly always spheres. Because a colloidal particle is much larger than its constituent atoms, its shape is determined by surface tension, not by its interior covalent bonds. The equilibrium and nonequilibrium behavior of colloidal suspensions is controlled primarily by the hard repulsive interaction between particles, and dense suspensions of identical hard spheres are known to form only fcc colloidal crystals1,2 or disordered, glassy packings. Despite this limitation, several new kinds of materials based on colloids have emerged in the past decade. Materials such as photonic crystals and macroporous media are made by drying or flocculating a dense suspension so that the particles touch and form a rigid, colloidal sphere packing. Since the colloidal length scale is commensurate with optical wavelengths, fcc colloidal crystallization is an inexpensive and simple way to prepare ordered materials that diffract light. Dried colloidal crystals can be used as templates3–5 to make photonic crystals that can function as optical semiconductors in a number of devices. The same templating procedures can be applied to either ordered or disordered particle packings to make macroporous materials, which can serve as flow-through catalyst supports, filters, and lightweight structural materials.6 MRS BULLETIN/FEBRUARY 2004 The properties of these materials depend sensitively on the microstructure of the colloidal sphere packing. In photonic crystals, grain boundaries formed during crystal growth and cracks formed during drying can incoherently scatter light, reducing the diffraction efficiency, whereas other types of defects such as vacancies can act as resonant cavities for specific frequencies, allowing us to create localized states in the optical spectrum. Unfortunately, there is no simple way to control the number and type of defects when making photonic crystals by packing spheres, nor is there a way to control the most important characteristic of the microstructure, the crystal structure itself. The fcc structure diffracts light much less efficiently than structures with a lower degree of symmetry, such as the diamond lattice.7 However, the spherical symmetry of colloidal particles leaves us with few possibilities for achieving the uniformly low coordination of diamond, in which each particle touches only four others. It is a challenge to control even the average coordination, which determines the connectivity of the pore network and hence the permeability in macroporous materials. Thus, there is great incentive to control the packing in colloidal materials. Several recent approaches have shown that we may at least be able to control the bulk crystal structure. We briefly mention a few methods here (and some are discussed in other articles in this issue). One approach is to change how the particles interact, either through synthesis or external fields. For example, spheres with a soft repulsive potential can form crystal structures such as bcc8 or A15 lattices.9 Other equilibrium phases can form if the spherical symmetry of the interactions is broken by inducing a dipole moment in the particles.10 Another approach is to perturb the natural crystal spacing of the particles, either by the addition of smaller spheres11 or by the use of a patterned substrate that defines a different lattice spacing.12 At sufficiently large perturbations, alternative crystal structures nucleate. Here, we discuss a more general approach to controlling not just the crystal structure, but also the defect structure and connectivity of colloidal materials. Instead of building materials by packing individual spheres together, we propose building them in two steps: first, packing the spheres into small clusters, or “finite packings,” then packing the packings. The advantage of this approach is that finite packings, unlike bulk sphere packings, are infinitely malleable: their structures vary with the definition of the boundaries that confine and the forces that consolidate the particles. As we show in the next section, finite packings can form a wider variety of structures than are found inside the fcc arrangement or its stacking variants. In fact, recent experiments on finite packing in colloidal systems have shown that it is possible to create large numbers of colloidal clusters with specific shapes and symmetries. These clusters, which we describe in the third section of this article, could become the building blocks of more complex materials. Finite Sphere Packings To illustrate the variability of finite packings, we consider a finite packing problem related to the “kissing problem”13 in mathematics: how many identical spheres can touch a central sphere of the same size, and what configurations do they form? A simple calculation shows that each particle touching the central sphere subtends a solid angle of 2 3 steradians. Even though the surface of the central sphere can accommodate nearly 15 [i.e., 42 3 objects of this size, only 12 spheres can fit.14 Much of the available coordination area is therefore unused. The most symmetrical arrangement of the 12 outer spheres is the icosahedral packing shown in Figure 1a. This structure has 12 axes of fivefold rotational symmetry. Figure 1b shows a very different arrangement, the asymmetrical “weary icosahedron,”15 made by rolling the spheres of the icosahedron toward one of its vertices. The empty region on the surface shows just how 91 Building Materials by Packing Spheres this packing is about 8% lower than that of a close-packed cluster when the spheres interact through a Lennard–Jones 6–12 potential, a mathematically simple potential used to model pairwise-additive attractions in atomic systems.16 If the particles are hard spheres, all packings have the same potential energy, so optimal packing must be defined by a geometrical criterion. As we discuss in the next section, a restriction on the mass distribution of spheres leads to the weary icosahedron.15 On the other hand, minimizing the volume of the packing, as defined by its convex hull, leads to an arrangement in which the particles form linear chains called sausages (see Figure 1g).17 If we change the number n of spheres for a given set of constraints, the optimal structures may differ even more dramatically. For hard spheres, it is not always obvious what physical constraints correspond to the geometrical conditions. Colloidal Clusters Figure 1. (a) An icosahedral arrangement of 13 spheres. (b) The “weary icosahedron.” (c) A 13-sphere subelement of the fcc lattice. (d) The close-packed cluster of (c) shown as a stacking of dense layers. (e) A 13-sphere subelement of the hcp arrangement, generated by rotating the upper layer of (c) by 180 . (f) The close-packed structure of (e), shown as a stacking of dense layers. (g) A 13-sphere “sausage,” the finite packing that occupies the least amount of volume. much coordination area is unused in any three-dimensional (3D) sphere packing. Because of the excess area, the 12 kissing spheres can be rearranged into infinitely many configurations. Two of the possible configurations correspond to local packings found in closepacked bulk structures. Figure 1c shows the local packing in the fcc lattice. Here, the centers of the outer spheres are located at the vertices of a cuboctahedron, which can also be viewed as a stacking of dense layers (see Figure 1d). The alternate stacking, in which the top layer of Figure 1d is 92 rotated by 180 degrees, is a local packing of the hcp arrangement (see Figures 1e and 1f), which has the same density as the fcc lattice. Any finite packing that corresponds to a local packing of an fcc or hcp crystal is called a close-packed cluster. If the only constraint on our 13-sphere finite packings is that they be kissing arrangements, then each of the configurations is equally valid. But other conditions or constraints can favor a single optimal structure. For example, if the spheres attract one another, the icosahedron is the most stable configuration: the energy of Creating clusters of hard spherical colloids requires first confining or isolating particles from a bulk suspension, consolidating them, and then “freezing” the structure by bonding the particles together. In two dimensions, the particles can be confined by functionalized patches18,19 or holes20,21 on a patterned substrate. As a suspension of spheres flows over the substrate, the confining wells isolate small groups of particles. Drying the suspension then consolidates each n-sphere group. The structures that result from this twodimensional (2D) finite packing process are optimal circle packings22 whose configurations depend on the shape and size of the confining well. If the well is circular, the particles form sphere doublets, triangles, squares, pentagons, and hexagons. All of these structures except the pentagon are elements of bulk 2D and 3D close packings. It is also possible to change the depth and cross section of micropatterned holes to allow the 2D structures to stack. In the resulting polyhedra, known as antiprisms, the upper layer is rotated with respect to the lower by one-half the vertex angle, yielding the tetrahedron (n 4), octahedron (n 6), and square antiprism (n 8), which is also a non-close-packed cluster. More complex arrangements are possible in either larger wells or in wells with different shapes. An even simpler way to confine the particles is to adsorb them onto a fluid interface. Solid particles attach to an oil–water interface to minimize the total surface energy of the three-phase system.23 The binding potential U per particle is given by U r 21 cos 2, (1) MRS BULLETIN/FEBRUARY 2004 Building Materials by Packing Spheres where r is the particle radius, is the oil– water surface tension, and is the bulk solid/oil/water contact angle. For particles 1 m in diameter, the binding potential is thousands of times the thermal energy. This effect can be exploited to convert the surface of an emulsion droplet into a 3D particle trap.24–26 Such droplets can consolidate as well as confine the particles.27 Removing the liquid from a droplet containing bound particles generates compressive forces that draw the particles together. Once the spheres touch on the surface of the droplet, the receding interface forms menisci between them, and the resulting capillary forces collapse the particles into a cluster. After all the oil has evaporated, van der Waals attractions freeze the structure. Surprisingly, this type of compression leads to structures that are unique and consistent for each value of n, as shown in Figure 2. The preferred structures range from familiar polyhedra such as tetrahedra, triangular dipyramids, and octahedra to more unusual polyhedra that have not been observed in either Lennard– Jones clusters or other systems with attractive potentials. The symmetry varies erratically with n, with two-, three-, four-, and fivefold rotational symmetry all occurring as a result of packing constraints alone. Two general properties of the packing sequence stand out. First, configurations of up to n 11 can be reproduced by a simple mathematical criterion: minimization of the second moment, M r r , enough. Thus, all eight deltahedra occur under certain packing conditions. Assembling Materials from Finite Packings n i 0 2 (2) i1 of a set of hard spheres, where ri is the center coordinate of the ith sphere and r0 is the center of mass of the cluster.15 This type of packing has not been observed before. For n 12, the observed clusters are not minimal-moment structures, but they lower their second moment during the packing process. Although we do not yet understand why the second moment defines the density in these systems, the correlation may provide some clues about the physics of the packing constraints. The second general property of the sequence is the occurrence of deltahedra, or polyhedra constructed from equilateral triangles. There are eight possible regular convex deltahedra,28 the first seven of which correspond to the observed colloidal clusters and the theoretical minimalmoment packings for n 4 through n 10. The eighth deltahedron is the icosahedron, but neither 12- nor 13-sphere minimal-moment clusters are icosahedra. In fact, the 13-sphere structure is the weary icosahedron of Figure 1b, and the MRS BULLETIN/FEBRUARY 2004 Figure 2. Scanning electron micrographs of clusters formed by particles on the surface of an evaporating droplet. Schematic illustrations show the sphere packings and polyhedra that minimize the second moment of the mass distribution. 13-sphere colloidal cluster we observe has one sphere displaced from this arrangement. The 12-sphere icosahedron appears to be a metastable arrangement; it rearranges to the minimal-moment structure when the drying forces are large Any of the colloidal clusters can be frozen in their optimal configurations and redispersed. In the surface templating method, this is done by sintering the particles and dissolving the substrate, a process that yields about 105 clusters of any type, of which 5% contain defects. In the emulsion trapping method, minimal-moment clusters of different n can be separated by centrifugation to yield 108–1010 identical, colloidally stable clusters. These clusters could let us tune the microstructure of colloidal sphere packings. In the simplest scenario, we may dope a bulk colloidal crystal with clusters made from the same type of spheres. The surface templating method is most appropriate for such experiments, since it yields a small amount of highly configurable clusters. When a colloidal crystal dries, the particles touch and form a close-packed fcc arrangement, but the addition of non-close-packed clusters would introduce specific defects. For example, hexagonal clusters of six particles can be made by packing spheres into circular micropatterned holes with posts at the centers. Such packings are essentially close-packed clusters that are missing a central sphere; they would be an excellent tool for introducing vacancies in photonic crystals. Other types of defects are also possible. The interstices in an fcc crystal are coordinated by either tetrahedral or octahedral arrangements of particles, while minimal-moment clusters can contain interior voids that are coordinated in many other ways. Doping a dried crystal with such clusters must therefore reduce both the density and the average coordination number. When the cluster has fivefold symmetry, as does the seven-sphere minimal-moment cluster or the 12-sphere icosahedron, it may introduce a significant amount of disorder into the bulk packing. We could use these methods to control the permeability in a macroporous material. As shown in the 13-sphere finite packing problem, 12-fold local coordination alone does not guarantee maximum density; thus it should be possible to control the two variables independently by adding the appropriate type and quantity of clusters. We may even be able to create disorder by design— using spheres and clusters to make bulk aggregates with specific structure factors.29,30 The clusters may also allow us to control nucleation in colloidal crystals, and thereby to improve the crystal quality for optical materials. Yin and Xia showed that adding a small amount of square (n 4) 93 Building Materials by Packing Spheres clusters to a dense suspension influences the epitaxial growth direction of colloidal crystals on flat substrates;20 however, little is known about how doping affects bulk crystal formation. There may be specific structures that enhance nucleation of metastable phases, for example, or that can lead to controlled stacking sequences in crystalline phases. The separation process for minimalmoment clusters yields enough material to pursue some more ambitious goals, including studying the phase behavior of some fundamental nonspherical shapes. The clusters themselves might then become building blocks for new ordered materials. Most of the minimal-moment structures are incompatible with an fcc arrangement of spheres, and there are few theoretical predictions of the types of phases that might be observed, although we can speculate based on the symmetry. It would be interesting to see, for example, if suspensions of tetrahedra could under some conditions form a colloidal crystal with diamond symmetry, the basis of an advanced photonic crystal. Suspensions of fivefold symmetrical clusters cannot crystallize, but they might form quasi-crystals. And mixtures of different clusters could form all kinds of packings, disordered and ordered, with a vast array of possibilities for controlling the microstructure of bulk packings. Conclusions An experimental study of the effect of colloidal clusters on bulk packing has yet to be completed, but there are numerous areas to explore, some of which we have listed here. Even more possibilities arise when we consider how other patterns of finite packing might arise. Some alternate strategies are suggested by the various methods of creating non-fcc packings. For example, we could break the spherical symmetry of the compressive forces on the colloidal particles stuck to a droplet surface by stretching the droplet or by inducing dipoles in the spheres. Also, mixing different sizes of spheres on the droplet surface may perturb the cluster polyhedra just as it perturbs the crystalline unit cell in a bulk system. More systematic variation of cluster configuration is possible with micropatterned templates. Some of these methods may unearth other mathematical sphere packing motifs, which may in turn allow us to develop some general empirical rules about local structure in a complicated configuration space. This is the inverse problem of assembling spheres into specific bulk packings: Can we “disassemble” or interpret the structure of disordered materials in 94 terms of finite packings? Frank16 first speculated that the local arrangements in disordered systems of attractive spheres correspond to finite packings that are more stable than close-packed clusters.31 Scattering experiments have now verified this hypothesis for metallic liquids.32,33 In these systems, the interatomic forces are well approximated by a Lennard–Jones potential, a type of interaction that favors the 13-sphere icosahedron, as we have seen. Icosahedra, whose fivefold symmetry is incompatible with long-range order, are indeed local packings in the liquid state. The stability of the icosahedron relative to a close-packed cluster entails an energetic barrier to rearrangement, thus hindering crystallization and allowing the liquid to persist at temperatures well below the freezing point. Relating finite packings to bulk phenomena in hard-sphere systems is more difficult. In a dense, disordered bulk packing, the forces on a local arrangement depend on the positions of all the other particles in the system—we cannot neglect the effect of particles far away. Near the glass transition of a hard-sphere colloidal system, for example, large groups of particles move simultaneously when the system is compressed.34,35 Researchers studying “jammed”36 systems in which particles cannot flow and glassy systems have only recently made progress in characterizing the forces and the local arrangements that can bear them. So while there is some evidence that local fivefold symmetry occurs in dense random packings37 and supercooled fluids38 of hard spheres, it is not yet clear if these local structures correspond to some kind of optimal finite packing. On the other hand, we have seen that specific kinds of compression lead to preferred finite packing structures. The isotropic compression of the evaporating emulsion droplet may be similar to the compression of a local arrangement in a disordered system. Though icosahedra have been the focus of most studies of local packing in hard-sphere systems, our clusters suggest that compressed hard spheres more generally prefer to form deltahedra— and as Bernal noted in 1960,39 none of the deltahedra with n 6 or combinations thereof can fill space. Perhaps nucleation in disordered packings is suppressed by deltahedral local packing rather than by short-range pentagonal or icosahedral order alone. Further experiments on colloidal systems should reveal whether minimal-moment structures are found in hard-sphere glasses, supercooled fluids, or jammed bulk packings. Given all of these possibilities, we believe that the microstructure of materials derived from spheres is more understandable and mutable than previously imagined. Viewing dense colloidal suspensions as collections of individual particles limits the way we approach organizing them. The physical reality is that the particles are correlated, and we might do better to think of dense suspensions as mixtures of stable and transient finite packings. Understanding the conditions that favor certain finite configurations will let us control defect placement, coordination, density, and crystal structure in the next generation of colloidal materials. Acknowledgments We thank the National Science Foundation (grants CTS-0221809 and DGE9987618) and Unilever Corporation for supporting our work on colloidal clusters. We also thank Mark Elsesser for contributions to the experiments. References 1. B.J. Alder and T.E. Wainwright, J. Chem. Phys. 27 (1957) p. 1208. 2. P.N. Pusey and W. van Megen, Nature 320 (1986) p. 340. 3. J.E.G.J. Wijnhoven and W.L. Vos, Science 281 (1998) p. 802. 4. A. Blanco, E. Chomski, S. Grabtchak, M. Ibisate, S. John, S.W. Leonard, C. Lopez, F. Meseguer, H. Miguez, J.P. Mondia, G.A. Ozin, O. Toader, and H.M. van Driel, Nature 405 (2000) p. 437. 5. Y.A. Vlasov, X.Z. Bo, J.C. Sturm, and D.J. Norris, Nature 414 (2001) p. 289. 6. A. Stein, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 44 (2001) p. 227. 7. K.M. Ho, C.T. Chan, and C.M. Soukoulis, Phys. Rev. Lett. 65 (1990) p. 3152. 8. Y. Monovoukas and A.P. Gast, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 128 (1989) p. 533. 9. P. Ziherl and R.D. Kamien, J. Phys. Chem. B 105 (2001) p. 10147. 10. A. Yethiraj and A. van Blaaderen, Nature 421 (2003) p. 513. 11. P. Bartlett, R.H. Ottewill, and P.N. Pusey, J. Chem. Phys. 93 (1990) p. 1299. 12. J.P. Hoogenboom, A.K. van LangenSuurling, J. Romijn, and A. van Blaaderen, Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 138301 (2003). 13. J.H. Conway and N.J.A. Sloane, Sphere Packings, Lattices, and Groups (Springer, New York, 1999). 14. K. Schütte and B.L. van der Waerden, Math. Ann. 125 (1953) p. 325. 15. N.J.A. Sloane, R.H. Hardin, T.D.S. Duff, and J.H. Conway, Discrete Comput. Geom. 14 (1995) p. 237. 16. F.C. Frank, Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Sci. 215 (1952) p. 43. 17. U. Betke, M. Henk, and J.M. Wills, Discrete Comput. Geom. 13 (1995) p. 297. 18. J. Aizenberg, P.V. Braun, and P. Wiltzius, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (2000) p. 2997. 19. I. Lee, H.P. Zheng, M.F. Rubner, and P.T. Hammond, Adv. Mater. 14 (2002) p. 572. 20. Y.D. Yin and Y.N. Xia, Adv. Mater. 13 (2001) p. 267. MRS BULLETIN/FEBRUARY 2004 Building Materials by Packing Spheres 21. Y.D. Yin, Y. Lu, B. Gates, and Y.N. Xia, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 (2001) p. 8718. 22. S. Kravitz, Eng. Mater. Des. 12 (1969) p. 875. 23. S. Levine, B.D. Bowen, and S.J. Partridge, Colloids Surf. 38 (1989) p. 325. 24. O.D. Velev, K. Furusawa, and K. Nagayama, Langmuir 12 (1996) p. 2374. 25. O.D. Velev, K. Furusawa, and K. Nagayama, Langmuir 12 (1996) p. 2385. 26. O.D. Velev and K. Nagayama, Langmuir 13 (1997) p. 1856. 27. V.N. Manoharan, M.T. Elsesser, and D.J. Pine, Science 301 (2003) p. 483. 28. N.W. Johnson, Can. J. Math. 18 (1966) p. 169. 29. S. Torquato, T.M. Truskett, and P.G. Debenedetti, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (2000) p. 2064. 30. S. Torquato and F.H. Stillinger, J. Phys. Chem. B 106 (2002) p. 8354. 31. D.R. Nelson, Solid State Phys: Adv. Res. Appl. 42 (1989) p. 1. 32. T. Schenk, D. Holland-Moritz, V. Simonet, R. Bellissent, and D.M. Herlach, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 075507 (2002). 33. K.F. Kelton, G.W. Lee, A.K. Gangopadhyay, R.W. Hyers, T.J. Rathz, J.R. Rogers, M.B. Robinson, and D.S. Robinson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 195504 (2003). 34. W.K. Kegel and A. van Blaaderen, Science 287 (2000) p. 290. 35. E.R. Weeks, J.C. Crocker, A.C. Levitt, A. Schofield, and D.A. Weitz, Science 287 (2000) p. 627. 36. C.S. O’Hern, S.A. Langer, A.J. Liu, and S.R. Nagel, Phys. Rev. Lett. 86 (2001) p. 111. 37. A.S. Clarke and H. Jonsson, Phys. Rev. E 47 (1993) p. 3975. 38. U. Gasser, A. Schofield, and D.A. Weitz, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15 (2003) p. S375. 39. J.D. Bernal, Nature 185 (1960) p. 68. ■ Advertisers in This Issue Page No. American Scientific Publishers 107 Brukers AXS Inc. Inside back cover High Voltage Engineering Inside front cover Huntington Mechanical Labs, Inc. Outside back cover MMR Technologies, Inc. 77 Pacific Nanotechnology, Inc. 77 J.A. Woollam Co., Inc. 90 Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc. 95 For free information about the products and services offered in this issue, check http://advertisers.mrs.org The New 2004 MRS PUBLICATIONS CATALOG is in the mail Not an MRS member? Contact MRS and request a copy today! [email protected] or 724-779-3003 For more information, see http://advertisers.mrs.org MRS BULLETIN/FEBRUARY 2004 www.mrs.org/publications/bulletin 95