* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Interspecific Competition and Species Co

Biodiversity action plan wikipedia , lookup

Introduced species wikipedia , lookup

Unified neutral theory of biodiversity wikipedia , lookup

Molecular ecology wikipedia , lookup

Storage effect wikipedia , lookup

Island restoration wikipedia , lookup

Biogeography wikipedia , lookup

Occupancy–abundance relationship wikipedia , lookup

Theoretical ecology wikipedia , lookup

Latitudinal gradients in species diversity wikipedia , lookup

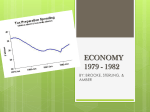

Nordic Society Oikos Interspecific Competition and Species Co-Occurrence Patterns on Islands: Null Models and the Evaluation of Evidence Author(s): Edward F. Connor and Daniel Simberloff Reviewed work(s): Source: Oikos, Vol. 41, No. 3, Island Ecology (Dec., 1983), pp. 455-465 Published by: Wiley on behalf of Nordic Society Oikos Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3544105 . Accessed: 21/02/2013 12:18 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. . Wiley and Nordic Society Oikos are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Oikos. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1983 OIKOS 41: 455-465. Copenhagen and speciesco-occurrence patterns competition Interspecific on islands:nullmodelsand theevaluationof evidence Edward F. Connor and Daniel Simberloff andspeciesco-ocD. 1983.Interspecific competition Connor,E. F. andSimberloff, - Oikos41: ofevidence. on islands:nullmodelsandtheevaluation patterns currence 455-465. rangesas evidence geographic Severalrecentstudieshaveadducednon-overlapping excludeoneanother. We havepreviously pointedout thattwospeciescompetitively exclusive is unusually ofspecies'co-occurrence thattoshowthata particular pattern withthatexpected theobservedpattern reason),one mustcontrast (forwhatever ofoneanother, allspecies, andonemustconsider werespeciesplacedindependently exclusive ranges.Furthermore, notonlythosethatappeara priorito haveunusually ofspecies'distribulargenumber evenwhenone is able to showthatan unusually non-distributional in the absenceof independent exclusive, tionsare improbably fortheseodd disotherreasonableexplanations evidencecapableof eliminating causeisresponsible oranyotherspecific onecannotinfer thatcompetition tributions, fortheobservedpattern. and alternative procedures, Otherworkershave critizedour methods, suggested andillusdamnedtheuse ofnullmodelsinecology.We respondto thesecriticisms Wealsoreaffirm ourviewthat procedures. trateproblems thatbesetthesealternative nullhypotheses in ecologyareuseful. CharlottesE. F. Connor,DeptofEnvironmental Sci.,ClarkHall,Univ.of Virginia, Deptof BiologicalSci.,FloridaStateUniv., ville,VA22903, USA. D. Simberloff, FL 32306,USA. Tallahassee, B HeKOIopbmOOBpeMeHHbDCHCcJeipBaHw HCfQTIb3Yi1TC5 HenepeepiaeBK4iOro- f Beta HcxJarpa4qeclce apeanL KacKgpKa3aTe~jicTBo, xTO xa KowypuyaIe iT apyr ypyra. Mu npeOrapmemao ycTaHoBHTm,rIO xSs Toro, qrio( noica3aaa, BFOB CoBaoerT scL pieqaeMvCm cmcXTaeTcs (no uotIMo B KOHKPeTH~bI cYqao &mibnpHwnnaM),cnenyT oonocTaBm Ha6naemwo cyTyawo C TaKog, me npanonaraeTCsl He3aBHCxHe pacrpmemHHe BO=B xyI OT xwyra; rlB 3TcmCnIewrT 0pacllipmnaTm BCe BHil, a He TobKO Te, KoTop aIpHOpHO HmiOTH&NHME nloKa~aTh,'ITO HeOO.HO 6oco6neHH apeam. Bonee Toro, xwak ecu Bo3mmmO o6ooo6leHo, rIpo oT01TTBmH 6owre acmu B~upmQx apeaJnoB HenpaBpQm6Ho cYIOoO6HOrO HCHe CB5[3aHHOIO c pacrpeeneHHem, He3asBHCHNrO rpKa3aTemcTBa, Kxhom xpyrue pe3oHIwe o61IcHeHSI BTHXIQgI03HEixapeaToB, HeJYbS3f3leJnaTb 3aY H m i HH5a cneWImecKaq npwwHa mme-T OTHm HIe K xmeme, 'mr KOHam ScHInnbHa6.IQna~y cnyqawo.B e HcanefopaTeni4 xpHTm oBam Hail! MeT, 3ynamTTpHaTMHbile meTow H OTptIaR ripHHPMocTh 0-rHrlOTObIB 31CKOJIC. MU 3mTHBThTePHZHTHBHL1em sTy KPHTHK H BOanPOH3BQPWM BOawmw~aem nu. mai Tam YTBeKgaeM HalWlyTOWY 3PeH}Iq 0 1pKaeHWMVCThB 3KQTK3H O-noroi. Accepted3 March1983 ? OIKOS 29* 45 5 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions We disagreewiththeseconclusions. First, byisolating thesethreeexamplesfroma largegroupof possible 141speciesofbirds evidenceexiststhatin- examples(Diamond(1975) reports Althoughsoundexperimental occursin nature(Wilbur1972, or9870 pairsofspeciesintheBismarck Islands)he has terspecific competion wideerrorrate"and Neill1975,Coen et al. 1981,CrowellandPimm1976, failedto controlthe"experiment theprobability ofmaking inflated hasgrossly Mungerand Brown1981, and others),the inference therefore thatthese thenullhypothesis in structuringa TypeI error,rejecting thatit is of overwhelming importance arenotunusualwheninfactitis true.This on ambigu- distributions is based primarily ecologicalcommunities thattheprobability of obous indirect evidence(e.g.,Diamond1975,1978). For is analogousto concluding fiveheadsina rowfromthetossofa faircoinis example,Terborgh(1971) and Terborghand Weske taining (1975) estimate thatbetween37% and71% oftheele- (0.5)5 = 0.0313,wheniftheeventis embeddedin a of vationallimitsof birdsalongtheVilcabambaof Peru longerseriesof cointosses,say 10, theprobability are determined by interspecific competition. Theyar- obtainingat least one run of fiveheads is actually rive at thisestimatesolelyby inspectionof known 0.1875 (6 X (0.5)5). The pointis that,yes,thesearexcluvegetation discontinuities and eachspecies'elevational rangements isolatedpostfactoare improbably thatare sive,butonewouldexpectbychancealonetofinda few distributions frequency distribution. Abutting to improbablepairwisearrangements when inspecting notcoincident withvegetation changesare inferred Widerspecies 9870 pairsofspecies.Second,to statethata particular exclusion. be maintained bycompetitive exclusive andtherefore is unusually rangeson another nearbymountain rangearealsoattri- geographic pattern theobserved onemustcontrast release.Evidenceof aggressive competitively produced, butedto competitive withthatexpectedwerespeciesindepenencounters betweenspeciesor rangeexpansionsafter distribution that Nor dently removalofa putative is notpresented. competitor placedon islandssubjectonlyto constraints is it shownthatindividual otherrelevantbiologically and environspecies'habitatpreferencesincorporate do notaccountfortheobserveddegreeof elevational mentally structure. determined Lastly,even werewe ofspecies' exclusivity (cf.DueserandHallett1980).Is thiskindof ableto showthatan unusually largenumber basisto inferthatspecies' geographic indirect evidencea sufficient patternsare improbably exclusive,in the distributions are determined Have we absence of independentnon-geographical evidence bycompetition? inanyinstance eliminated otherbiologically reasonable capable of eliminating otherreasonableexplanations in- fortheseodd distributions, hypotheses? Couldnotabutting distributions reflect one cannotinferthatcomevolvedhabitatpreferences, interaction petition causeis responsible forthe dependently oranyotherspecific witha predator or parasite,or purechance?In earlier observedpattern(Pielouand Pielou 1968,Simberloff papers(ConnorandSimberloff 1979,1983,SimberloffandConnor1981). andConnor1979,1981),we haveattempted to answer Previously (Connorand Simberloff 1979), we outthesequestionsbyexamining one classofindirect evi- lined a procedureto assess the null probability of dencethatis oftenadducedas evidenceofinterspecificobserving a particular amountof exclusivity in species data on geographical Our goals co-occurrence competition: patterns. patterns. Based upontheanalysesperif a formed were first,to developa procedureto determine withthisprocedure, weconcluded thatadducing particular geographical pattern wasindeedodd;second, a roleforcompetition inshaping species'co-occurrence if theseunusualpatterns to determine could bestbe patterns, over and above whateverrole competition ofinterspecific explainedbyan hypothesis competition,mayplayindetermining howmanyspeciesanislandhas or whether otherreasonableexplanations wereequally or howmanyislandsa speciesoccupies,is verydifficult plausible;andthird, to illustrate whatwe believeto be sincemanynon-overlapping distributions are expected the pitfallsof makingcausal inferences fromindirect fornon-competitive reasons.Recently, Diamondand evidence. pattern Gilpin(1982, 1983), Gilpinand Diamond(1982) and Commonwisdomholdsthatifinterspecific competi- Wrightand Biehl (1982), have criticized our procetion is an important forceshapinggeographical dis- dures.We wouldlike to reiterate our pointsand our thencompetitive tribution, exclusionshouldtendto analytical in an attempt procedure to relievewhatwe produce non-overlappingspecies' distributions.perceiveto be theconsiderable confusion thathas ariDiamond(1975) suggests thatthisis in facttrue,and sen overour interpretation of theseissues,and to rewellexemplified particularly bywhathe terms"chec- spondto ourcritics. kerboard"distributions of birdspeciesamongislands. He presents threeexamples(Figs20, 21, 22) involving two species in each of three genera of birds 2. The Connorand Simberloff procedure (Pachycephala,Ptilinopus,and Macropygia)in the Bis1. Introduction marckIslands.He contendsthatthegeographical patternwithineach genusis improbably exclusiveand therefore primafacieevidencethatcompetition is responsiblefortheexclusivity. Connorand Simberloff (1979) represented the distributon ofspeciesamongislandsas binary 0-1 matrices in whicheach columnrepresented an islandand each row a species.A species'presenceon an islandwas 456 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions nor and Simberloff (1979) suggested severalpossible causes forthe excessiveexclusivity observed,among themcompetitive exclusion,predation,geographical and unsettled speciation, We concludedby taxonomy. thatadducinga roleforcompetition stating in shaping quartets,etc. thatshare 0, 1, 2, 3, . . . N islandsis then species'co-occurrence overand above whatpatterns simplya counting problem(albeitnota smallone for ever role competition mayplay in determining how largespeciosearchipelagos). Fromthesecountstheac- manyspeciesan islandhas or how manyislandsa tualfrequency distribution oflevelsofexclusivity canbe speciesoccupies,is verydifficult sincemanyexclusive generated forpairsor largergroupsof speciesforany patterns are expectedfornon-competitive reasons. archipelago. At issue,however,is to whatexpectedamountof shouldtheobservedamountbe compared? 3. Criticismsof the Connor and Simberloffapproach exclusivity One could generatean expected distribution of 3.1. Owlsandhummingbirds exclusivity simplyassuming independent placement of species(a totallyunconstrained matrix).Such a dis- BothDiamondandGilpin(1982,1983) andWright and tribution wouldbe "trulynull"withrespectto species Biehl (1982) claimthatthe Connorand Simberloff butwouldlack realism.The factthat (1979) procedure co-occurrences, tendsto dilutetheeffect ofcompetismallislandshavefewerspeciesthando largeislandsis tive exclusion by ".... submerginginstancesof comwellestablished (ConnorandMcCoy1979).Thatsome petitorswithexclusivedistributions in an irrelevant speciesarerestricted tojusta fewislandsandsomeare massof data fromecologically remotepairsof species ." (Diamondand Gilpin1983). Wright widelydistributed is alsowellknown(Darlington and Biehl 1957, Cain 1944). To generatean expecteddistribution of (1982) feel thatone should ".... restrictthe analysisto exclusivity thatignoressuchubiquitous patterns leads specieswhicharepotential competitors". Whiletheasonlyto a further ofthecausesof anyap- semblyrulesproposedbyDiamond(1975) towhichwe confounding parentodd geographic pattern, anda markedtendency wereresponding werenotrestricted to guildsor "poto findthatrangesof speciespairsoverlapmorethan tentialcompetitors", we agreethatitwillbe difficult to expected. discernthe effectsof competition on biogeographic one cangenerate Alternatively, an expecteddistribu- patterns froma community-wide analysis.In fact,we tion of exclusivity thataccountsforspecies-areare- said exactlythat". . . statisticaltestsof properlyposed lationships and/orspeciesoccurrence distributions, To nullhypotheses willnoteasilydetectsuchcompetition, generatean expecteddistribution of exclusivity thatis sinceit mustbe embeddedin a massof non-competinullwithrespectto speciesco-occurrences, yetposses- tivelyproduceddistributional data" (Connorand Simses otherrelevant biologically andenvironmentally de- berloff 1979). termined structure (such as species/area relationships However,restricting theanalysistoguildsor "potenandspeciesoccurrence distributions), ConnorandSim- tialcompetitors" is nota simplematter, sinceto do so berloff (1979) generated a seriesofbinary with requiresassigning matrices speciesto guildsor a determination rowand columnsumsidenticalto thoseof theactual of whichspeciesare in fact"potentialcompetitors". matrix. However,to assurethattheexpectedmatrices Partitioning all thespeciesina community intoguildsis were nullwithrespectto speciesco-occurrence pat- no easytaskandrequiresdataon resource use foreach terns,presencesof species(l's) wereplacedindepen- species(Root 1967). Krebs(1978) contendsthat"no dentlyand uniform randomly subjectonlyto rowand one has yetbeen able to analyseall the guildsin a columnsumconstraints. Thisprocedure wasperformed community". Thosestudiesthathavedelineated guilds repeatedlyto generatethe expectedfrequencyof have reliedon massiveamountsof fielddata (Root speciespairsor triosand itsvarianceforeach levelof 1967,Feinsinger 1976,AlataloandAlatalo1979).For exclusivity, i.e.,howmanypairsortriosareexpectedto no singleguild,muchlesstheentireaviancommunity, share 0, 1, 2, . . . islands.The actual and expecteddis- have Diamond and Gilpin(1982, 1983) eitherdetributions ofexclusivity werethencomparedusinga x2 lineatedtheguildor presented theevidencenecessary statistic. tojustify theguildboundaries. Furthermore, evenwere Employing sucha procedure, ConnorandSimberloffone able to delineatea singleguildsatisfactorily, its (1979) examinedthreefaunas.Theyobservedforthe geographic of speciesco-occurrence pattern couldtell New Hebrides birds a close agreementbetween us littleaboutcompetition in general.Not onlycould observedand expecteddistributions of exclusivity and different guildsbe structured by different forces,but fortheWestIndiesbirdsandbatsan excessivenumber also one wouldneedto knowthenullprobability that, of exclusivearrangements. However,in thelattertwo of the N guildsexamined,one or moreguildswould examplesa verylargenumberof allopatricarrange- producea pattern thatwouldhavebeenstatistically odd mentswasexpected, eventhoughtheexpectedwassig- hadonlythatsingleguildbeenexamined. Ifa fewguilds nificantly lowerthantheactuallevelofallopatry. Con- are chosenrandomly, and notselectedbecauseof the indicatedby a 1 and an absenceby a 0. Exclusiveor exclusivedistributions could thenbe recogpartially nizedas pairsorgroupsofspecies(rows)inwhichno,or just a few,matchesof l's occuracrossthe columns. Determining theactualnumberof speciespairs,trios, 457 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions of a competitive likelihoodof detecting effect, stronger absencescan be explainedby thejointdistribution themarginal totals.However,justas incontingency inferences canbe made. tathenumberof the analysisto only "potentialcom- ble analysis,forcertainfixedmargins Restricting can be so smallthatstatistical petitors" is equallyproblematic, sinceone mustdeter- possiblerearrangements minea prioriwhichof thetotalpossiblesetof species significance cannotbe achieved.We have already of speciesco-occurWhilean accu- shownthatthe possiblepatterns pairsinvolve"potentialcompetitors". rateassessment toof thisis aptto be as laboriousas de- rencesachievablesubjectto a fixedsetofmarginal thatare statistically odd.The lineating guilds,one couldexaminegroupsarbitrarilytalscan includeinstances forthe West Indies defined orany observedpatternsof exclusivity bytaxonomy, bodysize,billmorphology, In factwedidso for birdsandbats(ConnorandSimberloff othereasilyobserved characteristic. 1979) arestatisunusualarrangements in all threeexampleswe examined, tically are surprising. taxonomic families Statistically and Vuilleumier and Simberloff a also achievablefortherowandcolumnsumsobserved (1980) performed similar fortaxonomic, andrandomly forthe New Hebridesbirds(Connorand Simberloff analysis ecological, partitioned paramobirdfaunas.In anyevent,one can- 1983), but the observedpatternof speciesco-occurnotfocussolelyonthegroupof"potential competitors" rencesintheNewHebridesbirdsisnotoneoftheseodd sinceto concludethata particular levelof exclusivitypatterns. among"potential is odd,one mustshow Wereone able to demonstrate competitors" thatcompetition had thatsuch a patternis odd relativeto the level of affected themarginal thenfixing distributions, themarexclusivity observedforspeciesnot consideredto be ginalsto equal the observedtotalswouldbe at least "potential competitors". somewhatcircular.As we mentioned above,without We agreethatan analysisbasedon guildsor "poten- fixing someofthemarginal totals(rowsums,forexamtial competitors" wouldbe interesting. In eitherin- ple), it is impossible to generatea reasonablenullexstance,to determine the correctnullprobability of a pectation ofexclusivity foranyparticular If archipelago. particular patternof speciesco-occurrences requires we mustconcludethatthemarginal totalsare affected one to examinethe entirefauna,not merelythose bycompetition, andtherefore cannotfixthetotals,then speciesthought mostlikelyto be competitors. itbecomesimpossible to testthenullhypothesis thata ofspeciesco-occurrence particular pattern isnotstatisticallyodd. If thisis whatGrantand Abbott(1980) 3.2. Hidden structurein the marginalconstraints thentheyarearguing intend, thatitis impossible totest Diamondand Gilpin(1982, 1983) claimthatbycon- an hypothesis the causes of geographical concerning the expectedrearrangements straining of speciesdis- arrangements solelyfromdata on geographical artributions to satisfy theobservedmarginal totals(row rangements. Butthisis ourverypoint!One cannotfrom and columnsums),one builds"hiddenstructure" into geographical dataaloneeasilydetermine thecausesofa thenullexpectation ofexclusivity. In otherwords,they geographical pattern. feelthatcompetition hasalreadyaffected thenumber of Wrightand Biehl (1982) feel thatfixingthe row speciesfoundon an islandandthenumber ofislandsa sums,the numberof islandson whicheach species speciesoccupies.Although DiamondandGilpin(1982, occurs,is a reasonableapproachto generating a null 1983)present noevidencethatcompetition hasaffected expectation ofspeciesco-occurrence patterns (see disthemarginal totalsor thepattern ofspeciesco-occurr- cussionof alternative proceduresbelow). However, ences,it is surelypossiblethatcompetition does affect theypointoutthatbyalso fixing thenumber ofspecies thespeciesrichness ofan islandorthegeographic range on an island,as we did,our procedure failsto detect of a species,as we clearlystated(Connorand Simber- significant in speciesco-occurrence aggregation patloff1979: 1136). This need not necessarily translate terns.Once again,but for a different reason,it is intoalteredco-occurrence patterns, however. Themar- suggested thatour procedureis not"trulynull".But, ginaldistributions of the row and columnsums,not theintent ofouranalysiswasnotto determine ifthere singlemarginal totals,settheconstraints forrearrangingwas any evidencefornon-randomness in speciesdisthepatterns ofspeciesco-occurrences. One mustshow tributions amongislands.We firmly believethereis! A thattheshapeorlocationsofthemarginal distributionsvisual inspectionof a presence-absence matrixof are affected bycompetition to concludethatfixing the speciesinalmostanyarchipelago willrevealthatspecies to equal theobservedvaluesbuildsin "hidden areaggregated. margins Thisis largely becausethephysical constructure". ditionsand habitatsnecessary fortheestablishment of GrantandAbbott(1980) raisethespecterthatfixing speciesinparticular taxaarealso aggregated. Thisvery themarginal totalsfortheexpectedrearrangements to aggregationis at least partiallyresponsiblefor equal theobservedis alwayscircular. Eitherthisis not species-area relationships. Ourprocedure wasdesigned true,ortheentirepremise ofcontingency tableanalysis to examinethepattern of speciesco-occurrences after is wrong,since,in a manneranalogousto contingencysuchaggregation had been factored outbyaccounting tableanalysis,we are askingif the co-occurrence as- forspecies-area relationships, notto ask merelyifany pectsoftheobservedpattern ofspecies'presences and non-randomness is evidentin speciesco-occurrence 458 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions each It is interesting to notethatthe procedures all pairsof speciesequallyratherthanweighting patterns. thata randomarrangement of advocatedbyDiamondandGilpin(1982, 1983) andby pairby theprobability as excluoutthisaggrega- thatpairwouldhaveproduceda distribution Wright andBiehl(1982) failto factor theycontendthata tion,and thattheytherefore concludethatspeciesare sive as thatobserved.Essentially distributed non-randomly allopatric speciesis lesslikely among islands. But, the pairofwidelydistributed thanis a pair observednon-randomness is a tendency towardsag- to havearisenbyindependent placement distributed gregation, notexclusion.Wherein thisresultis there of narrowly allopatricspecies.Again,we wereresponding to Diamond's(1975) assembly evidenceofcompetition? rules, certainspecies whichstatenothingabout weighting groups,onlythatexclusivedistributions occur,and do 3.3. Checkerboards as Diamond so forcompetitive reasons.One canweight Diamondand Gilpin(1982, 1983) questionthepower and Gilpin(1982, 1983) suggestusingourprocedure, thebookkeeping choresassociatedwith ofourtestbyclaiming thatitfailsto recognize as non- butperforming random". . . the simplest,clearest,and most non-ran- counting thenumberofexclusive pairsor triosslightly dom pattern causedby interspecific . . .", differently. For each rearrangement of speciesprecompetition checkerboard. namelya perfect On thecontrary, per- sencesandabsencesgenerated subjecttothefixedmarfectcheckerboards are notnecessarily causedbycom- ginal totals,one can countnot only the expected petition,nor are the samplesof checkerboards pre- numberof pairs,trios,etc. with0, 1, 2, 3, . . . N co-ocsentedby Diamondand Gilpin(1982, 1983) unusual. currences, butalsorecordsimilar information as a funcTheycomputetheprobability ofobserving a particular tion of the combineddistributional breadthof the checkerboard distribution subjectonlyto fixedrow speciesin a group.For example,one can generatethe sums.This,however, allowsdegenerate rearrangementsexpectednumberof species pairs whose combined ofspeciespresences andabsencesthatinvolvesiteswith occurrencetotals (row sums) are 2, 3, 4, .. . 2N that no species(Connorand Simberloff 1983). Whyshould displayeachlevelofco-occurrence. As an examplewe thenullexpectation of speciesco-occurrence suchan analysisfortheWestIndies patterns have performed fora specific groupofislandscountrearrangements that bats (Fig. 1). While once again by x2 analysisthe includeonlya subsetoftheactualsites?Whenexpecta- observedand expecteddistributions are significantly tionsof exclusivity are computedsubjectto fixedrow different (x2 = 105.16, df = 57, p < 0.0005, cells and columnsums,no degenerate rearrangements are lumpedso thatno expectedvaluesare lessthan1 and allowed,andtheexamplesofcheckerboards presented less than20% are less than5) one can also see that byDiamondandGilpin(1982, 1983) areshownnotto certain categories ofcombined occurrence breadth have differ fromexpectation (ConnorandSimberloff 1983). an excessivenumberof exclusivepairs.Determining whichofthesedemandsomecausalexplanation andthe of the nature cause requires evidence other than thaton 3.4. Technical flaws geographical distribution. Theremaining criticisms lodgedbyDiamondandGilpin (1982, 1983) againstourprocedure concern thetechnical detailsof our analysisratherthantheapproachto the null expectationof exclusivity. generating procedures They 4. Alternative chastizeus forusingMonteCarlo procedures rather 4.1. The Diamondand Gilpinprocedure thanemploying an explicit solutionto generate thenull distribution of exclusivity. Whilewe agree thatthis To overcomewhattheybelieveto be theshortcomings wouldbe desirable,it is certainly notnecessary. Fur- of our procedureGilpinand Diamond (1982) and no explicitsolutionexistsevento countthe Diamondand Gilpin(1983) havesuggested thermore, theirown number ofpossiblematrix rearrangements forfixedrow 4-stepprocedure: andcolumnsums,muchlessforthenulldistribution of fromthispopulation exclusivity ofrearrangements. 1) Computethe probability that the i'th species Theycontendthatourtestcannotdetectthedirection occurson thej'thislandas pij= Ri Cj/TwhereRi is ofanyobservednon-randomness. Butthiscancertainly thei'thcolumnsum,Cj is thej'throwsum,andT is be accomplished byan inspection ofthedeviations bethegrandsum(numberof l's in thematrix). tweenobservedand expected,and byan inspection of 2) Computetheexpectedoverlapbetweeneachpair theindividual cell contributions to thex2statistic. ofspeciesand itsstandard In deviation fromtheabove thoseinstances wherewe concludedthattheobserved probabilities. The expectedoverlapbetweenspeciesi and expecteddistributions and k isEik = Ij pijPki and itsstandard differed, we indicatedthe deviation is directionof the difference (Connorand Simberloff SDik = V PHPkj(1-pj Pkj)1979). Theirtestcan do no better. 3) Standardize theobservedvaluesby substracting The lastpointraisedbyDiamondand Gilpin(1982, theexpectedand dividing bythestandard deviation 1983) in criticism of ourprocedure is thatit considers oftheexpected(dik = (Pik- Eik/SDik)), wheredik is 459 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 4~~~~~~~4 16~~~~ Fig.1. Deviationofobserved fromexpectednumber ofislandssharedforpairsofbatspeciesintheWestIndiesas a function of thecombined occurrence frequency ofeachspeciespair.The plottedvaluesaretheindividual cellcontributions ([0 - E]2/E)to theoverallx2statistic reported inthetext.Data arefromBakerandGenoways (1978). theobservedoverlapexpressedas standard deviates oftheexpected, and Oik is theobservedoverlap. 4) Comparethe frequency distribution of standardized observations to a (0,1) standardnormaldistribution via x2,and a graphical representation. degenerate. Thispracticelowersthenullprobability of observing anyspecified levelof exclusivity and biases theirtestin favorof rejecting the nullhypothesis of independent speciesplacement (ConnorandSimberloff 1983). Furthermore, thosearrangements thatare not degeneratemay possessmarginaldistributions quite Ifthenullhypothesis ofindependent speciesplacement different fromtheobservedmarginal so distributions, is true,thehistogram ofstandard deviatesshouldfollow thattheexpectedpatternof speciesco-occurrences is a (0,1) normaldistribution. An excessivenumberof confounded withthisvariation inthemarginal distribuspeciespairsin theuppertailofthedistribution would tions. indicatesignificant aggregation, and an excessin the GilpinandDiamond's(1982) motivation forthisaslowertailsignificant exclusivity. pectoftheirprocedure is to removethe"hiddenstrucwe applaudthespiritofthismethod, Although inas- ture"theyfeelisbuiltinbyfixedmarginal distributions. much as it representsan attemptto test the null However,thisapproachfailsto removesuch"hidden ofindependent hypothesis speciesplacement amongis- structure"; ratherit merelyobscuresanyrelationship lands,severaltechnical problems besetthistechnique. betweenthe marginaldistributions and the observed patternof species'co-occurrences sinceit obliterates themarginal distributions. Our procedure admitsthat "hiddenstructure" could affect the marginal distribu4.2. Expectedor fixedmarginal distribution tions,so we proceedbytesting thenullhypothesis that The computational procedureused by Gilpin and above andbeyondwhatever "hiddenstructure" is imDiamond(1982) and Diamondand Gilpin(1983) to partedby the marginaltotals,the patternof species generatetheexpectedoverlapbetweenspecieseffec- co-occurrences can be explainedto resultfromindetivelysetstherowand columnsumsfortheexpected pendentplacement.Were the Gilpinand Diamond speciesco-occurrence to be on averageequalto (1982) procedurecapable of removing pattern the so-called theobserved rowandcolumnsums,rather thanequalto "hiddenstructure", thenwe suggesttheterm"hidden theobservedsums,as we did. In doingso, theGilpin structure" to be a misnomer. Rather,"hiddenstrucand Diamond (1982) procedurecountsdegenerate ture",ifit exists,willremainhidden.Whatever strucrearrangements withspeciesoccurring nowhereand/or tureis impartedto the patternof speciesco-occurrsiteswithno speciesas possiblenullrearrangements.ences,hiddenor otherwise, by themarginal distribuThis,in essence,allowsmoredegreesof freedomin tionsshouldbe clearlyattributable to themarginal disrearranging the matrixof speciespresenceand ab- tributions. This can onlybe achievedif the marginal sences,butmanyoftheseadditional rearrangements are distributions are fixedand therefore known. 460 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions the patternof erfulregarding questionsconcerning species'co-occurrences (Connorand Simberloff 1978, The procedure forcomputing theprobability thatthe Simberloff 1978),theywerenotintended to primarily i'thspeciesoccurson thej'th island(step1) does not testsuchhypotheses. Theseprocedures weredesigned computeprobabilities. It computesexpectedfrequen- to testhypotheses thesimilarity of sitesin concerning cies. As mentionedby Gilpinand Diamond(1982) theirspeciescomposition, notthesimilarity of species thesevaluescan exceed1, and oftendo (Connorand distributions havebeen amongsites.Similarprocedures Simberloff 1983). Gilpinand Diamond(1982) adopt developedforand appliedto paleobiogeographic and severalad hocmethods to dealwiththisproblem. applications(Raup and Crick 1979, They biostratigraphic further claimthattheirprocedure confollows thetraditional Harper1978). Once againthetestedhypotheses log-linearmodelof contingency tableanalysis.How- cernsimilarity betweensitesor within sitesovertime. ever,suchan analysis is appropriate forfrequency Theprocedure andBiehl(1982) suggested byWright data, notbinary presence-absence data.Itisnotpossibletofit to supplantours (Connorand Simberloff 1979) for a log-linear or a logistic modelto these"probabilities" examining how manysitesa groupof speciesshares, (Bishopet al. 1975). Of theseveralwayssuggested theprobability a patofobtaining by startsbycomputing Gilpinand Diamond (1982) to estimatecell prob- ternof speciesco-occurrence as exclusiveas or more abilitiesonlytheMonteCarloprocedure is correct. We exclusivethanthatobserved.The computation is perhavealreadypointedoutDiamondandGilpin's(1982) formed for each species pair and follows the aversionto MonteCarlomethods. hypergeometric distribution suggested by Connorand Simberloff ofthenumber (1979: 1133).An expectation of sites shared between can also be computed species 4.4. Asymptotic normality andBiehl1982). (Wright The laststepin theprocedure outlinedby Gilpinand Using this procedure,Wrightand Biehl (1982) Diamond(1982) is to comparetheobservedfrequency examined fourpairsofspecies,thethreeavianexamples ofstandard deviates(step4) to a (0,1) normaldistribu- adducedbyDiamond(1975) as evidenceofcompetitive tion.Thiscomparison is predicated on theassumption exclusion, andLacerta lizardsintheAdriatic. Theyalso that,givenno speciesassociation,the observedfre- examinedtheNewHebridesbirdsandtheWestIndies of standarddeviateswould be bats. quencydistribution asymptotically (0,1) normal.We ask,asymptotic with The Wright and Biehl (1982) procedure essentially respectto what?We haveno analogofsamplesize in fixesthe row totalsof the expectedspecies' presthisproblem, so onecannotobservethebehavior ofthe ence-absence matrix to equaltheobserved, butletsthe of standarddeviatesforlargersamplesto columntotalsvaryfreely. distribution As we statedabove,thisfails ifit is, in fact,asymptotically determine normal.Why to constrain theexpectedpatternof speciesco-occurassume normality? Could the null distribution be rencesto accountfortheomnipresent species-area reskewedor leptokurtic? theoutcomeof the lationship Obviously, andtherefore tendsto bias theirtesttoward X2testis verysensitiveto theshapeassumedforthe rejecting thenullhypothesis. Again,thequestionofinexpecteddistribution of standarddeviates.If thetrue terestis whether or nottheobservedpattern ofspecies expecteddistribution is skewed,thenthe conclusions co-occurrence is consistent witha hypothesis of indereachedby Gilpinand Diamond(1982) fortheNew pendentplacement, giventhe observedspecies-area Hebridesand Bismarcksavifaunasmay be wrong. relationship andspeciesoccurrence distribution. Thisis However,without a meansofassessingtheasymptotic thehypothesis ourprocedure wasdesigned to test.Had behaviorof theexpecteddistribution of standardde- we been interested in askingsimplywhether thereis viatesit is impossibleto tell. This rendersrigorous evidenceofnon-randomness inspecies'distributions, as hypothesis testingbased on the Gilpinand Diamond Wright andBiehl(1982) appearto be, we wouldhave (1982) procedure rathertenuous. fixedneither therownorthecolumnsums.However, sucha testwouldnotbe particularly interesting sincewe know to species be non-randomly distributed withre4.5. TheWright andBiehlprocedure spect to the physicalenvironment, particularly at a andBiehl(1982) feelthatourprocedure Wright (Con- geographic scale. norand Simberloff 1979) and otherswe haveoutlined In fact,we used the veryproceduresuggestedby (Connorand Simberloff 1978, Simberloff 1978) are Wright andBiehl(1982) tocompute theprobabilities of "notappropriate to determine whether islandcoloniza- obtainingby independentplacementthe levels of tionis random".Theysuggestan alternative approach exclusivityobservedforMacropygiaand Pachycephala thattheyfeelis "betterabletodetecttheeffect ofcom- as presented by Diamond(1975), (Connorand Simpetitiveexclusionon insulardistributions". Whilewe berloff1979: 1133). For Macropygiawe calculated agreethattheprocedures we havedevelopedto com- identical probabilities, butWright andBiehl(1982) apputean expectation of the numberof speciesshared pearforPachycephala to haveerredintwoways.First, betweensitesarenotparticularly informative norpow- usingtheirspeciesfrequencies, we findtheirpublished 4.3. Cellprobabilities 461 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Tab. 1. Hypergeometric tailprobabilities thatindependent speciesplacement wouldhaveresulted inexclusivity as extreme as that observedforfourselectedspeciespairs. Numberofislandswith Neither Species Species Both species 1 only 2 only species Ptilinopus Pachycephala Macropygia Lacerta 3 21 17 21 17 13 30 11 18 18 14 18 15 14 14 28 9 9 12 18 11 6 6 18 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 Data source Hypergeometric probability 0.0003 Diamond(1975), Fig.22 0.0903 Diamond(1975),Figs22,8,15 andtext,p.357 0.0034 andBiehl(1982),Tab. 1 Wright 0.0035 Diamond(1975),p. 390 0.0037 Diamond(1975),Fig.21 0.0245 Diamond(1975), Fig.20 0.1226 Diamond(1975),Figs20,6,25 andtext,p. 357 0.0000001 Nevoet al. (1972) value(theirTab. 1) too lowbya factorof 10. Second, exclusivity appearsextraordinary. We cannotpresenta Diamond(1975) statesin histextthat11 islandssup- generaltreatment of the bias thatthisnon-indepenportP. pectoralis, 18 support P. melanura dahliaand21 dence will likelyproduce,but the following simple support neither. His figure 21 has,foranalogoustotals, exampleshoulddemonstrate theproblem.Wright and 11, 15, and 17, respectively. Wrightand Biehl have Biehl (1982) chooseto call a biogeographic arrangeused 12, 14, and 17, respectively. Tab. 1 depictsthe ment not predominantly interactiveif the null correcthypergeometric forall threecon- hypergeometric probabilities ofindependent probability is placement figurations, as wellas fortheotherexamplesgivenin lessthan0.05 foratleast5% ofthepairs.Supposethere Tab. 1 ofWright and Biehl(1982). A secondpointof were 12 speciesin a speciespool, arrangedover 10 interest arisesfortheothertwoexamples, Macropygia islands.Supposefurther thatspecies1,2, 3, and4 were andPtilinopus, in theirTab. 1 fromDiamond(1975). each foundon 5 islands,and thatstrictcompetitive FromDiamond'sFigs6, 8, 15,and25,andhistextonp. exclusion existedbetweenspecies1 and2, 2 and3, and 357,itis apparent thathisFigs20 and22 greatly under- 3 and4. Finallysupposethattherewereno interactions estimatethenumberof islandswithneither speciesof betweenanyotherspecies.Thatis,exclusive pairscomMacropygia andPtilinopus, respectively. Whenthedata prise3/(1') = 4.5% of all pairs.Now,let A, B, C, D, fromthefull50 surveyed islandsare included, thenull andE be theislandsoccupiedbyspecies1. ThenF, G, probabilities (ourTab. 1) are insignificant. H, I, andJmustbe theislandsoccupiedbyspecies2, so In anyevent,as we notedearlier,thesefourpairwise thatspecies3 mustoccupyA, B, C, D, and E. Then examplesofWright andBiehl'sTab. 1 areculledfroma species4 mustoccupyislandsF, G, H, I, andJ,and 1 massofbiogeographic data precisely becausetheyap- and4 arethusexclusively eventhough arranged thereis peared,a priori,to constitute unusualexclusivity. Un- no interaction betweenthem.The nullhypergeometric lessall availabledataare analyzedsimultaneously, one probability foreachofthe4 exclusive pairsis0.004,and cannotassessthe statistical significance of some par- therearethusatleast4/(12)= 6.1% ofthespeciespairs ticularsubset.For thethreeavianexamplesfromthe exclusiveat thislevel.Theremaybe others,produced BismarckArchipelagoneitherthe matrixsimulation by chancealonein theuniform randomplacement of methodnorthepairwisehypergeometric method(but theremaining 8 species,butjust these4 pairswould expanded to all pairs) can be applied since the causethesystem tobe classified as interactive byWright biogeographic data describedby Diamond(1975) as and Biehl (1982), even thoughtheactualnumberof "givenbyMayrand Diamond1975" haveneverbeen interactions is too lowbytheirstatedcriterion. published. one cannottellwhether Consequently three One can conceiveofothersimplesituations producsuchexclusively arrangedpairscould have arisenby ingspuriousassociations, eitherpositiveor negative. If independent placement. ForLacerta,Nevoetal. (1972) species1 and species2 wereobligatemutualists, for haveperformed introduction experiments thatbuttress example,and species 1 and species3 competitively theirconclusionof competitive exclusionbetweenL. excludedone another,species2 and 3 (givenan apsiculaandL. melisellensis. propriate number ofislandsandoccurrences) wouldbe Even whenthedata forall speciesin a pool are av- improbably exclusiveby the pairwisehypergeometric - assessing test,eventhoughtheydo notinteract. ailable,theWright andBiehl(1982) method One can sayin the null hypergeometric probabilities forall species generalthatlookingat all pairs,as Wright and Biehl pairsinthespeciespool- is defective. Thespeciespairs (1982) suggest, willlikelylead to overestimation ofthe arenotindependent ofone another andthismayeasily degreeofbiological structure. The GilpinandDiamond inflatethe observednumbersof speciespairswhose (1982) procedurewhichalso examinesall pairs,al462 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions to thoughnotusinghypergeometric suffers 6) All thisis to saythatnotonlywillit be difficult probabilities, simulation method concludethat a patternof speciesco-occurrence fromthissameproblem. Ourmatrix is An exactlyanalogous statistically odd,butalsothatdataon geographical does not producethisartifact. patbasisto determine the problemwas recently notedby Meagherand Burdick ternsalone are an insufficient (1980) withrespectto nearestneighboranalysis.To causesofthosepatterns. ifindividuals determine oftwospeciesor sexesare arinspace,sincepairsofindividuals Althoughwe feelthatGilpinand Diamond's(1982) rangedindependently andBiehl's(1982) procedures are notindependent ofone another(ifone knowsthat andWright areincorrect ofA's andinappropriate, A is B's nearestneighbor, theirintent is to testnullhypotheses one'spriorassessment nearestneighboris modified), thetraditional Thiswe applaud.It is certainly x2con- againstalternatives. a is invalid;theteststatistic is notdistri- refreshing changefromthecommonpracticeofinvoktingency analysis butedas x2.Meagherand Burdick(1980) use a re- ing,post hoc, competition as the cause of exclusive to generatethedistribution. peatedsimulation speciesranges(Diamond1975, 1978,Terborgh1971, Terborgh and Weske1975). However,in theviewof Diamondand Gilpin(1982, 1983) and Wrightand Biehl (1982), competitiveexclusionstill holds a 5. Discussion totheotherpossiblecauses paramount relative position Our messageis simpleand short,so we reiterate. ofexclusive Availableevidencedoesnot arrangements. seemto us to support thisview. ofspeciesco-ocIn thisrespect, 1) In orderto inferthatsomepattern we pointoutthatinspiteofthestrikcurrenceis odd, one mustknowwhatis expected. ingconcordance in resultsbetweenourprocedure and some hypothesis Therefore, observedand thoseof Gilpinand Diamond(1982) and Wright contrasting and expectedpatterns ofco-occurrence mustbe statedand Biehl(1982), theseauthorspersistin theirviewthata tested.Thishypothesis caninvolveeithera comparison case forcompetitive exclusioncan be builton biogeooftheobservedpattern ofco-occurrence withthatex- graphicdataalone.FortheNewHebridesbirdsGilpin pectedgivenindependent ofspeciessubject and Diamond(1982) found,as did we, no excessof placement to fixedmarginal or a comparison ofthe exclusivespeciesrangesoverthatexpectedfromindedistributions, co-occurrence forspecieswithin pattern de- pendentplacement.Wrightand Biehl (1982) found arbitrarily finedgroupsof"potential competitors" withthatco-oc- onlya slightexcessof aggregative over arrangements currencepatternexpectedof non-competitors. Other thatexpectedforboththeNewHebridesbirdsandthe are possible,buttheremustbe somenull West Indiesbats,whilewe foundsignificantly comparisons more hypothesis. exclusivepairsof speciesthanexpectedin the West of species'co-occurrence 2) The expectation should Indiesbats.For theBismarckIslandavifauna,Gilpin accountfor species-arearelationships and species' and Diamond(1982) also foundan excessofexclusive occurrence distributions. distributions overexpected, buttheexcessisvanishingly 3) An excessivenumberof exclusivelydistributedsmall(Gilpinand Diamond1982: Fig. 4). Since the speciesis consistent withan hypothesis ofcompetition,Bismarck dataareunpublished, we cannotapplyeither butcanalsobe explainedas resulting from severalother ourmatrix simulation approachor thehypergeometric causes,i.a., geographical speciation, multiple coloniza- calculations. The patternstrikingly evidentfromboth tionroutes,predation, and independentlyGilpinand Diamond's(1982) and Wright parasitism, and Biehl's evolvedhabitatpreferences. is one ofa significant (1982) analysis tendency towards 4) Since a uniquecause cannotbe associatedwitha aggregation in speciesco-occurrences. Wherein this classofco-occurrence particular patterns, itis impossi- resultis thereevidenceof an overwhelming pattern ble basedsolelyon biogeographical evidenceto infer evenconsistent withcompetitive exclusion, muchless thatcompetition oranyotherspecific causeis responsi- causedbycompetition? ble fora particular geographic pattern. Evidenceofactivereplacement orcolonizations thatfailedbecauseof activeexclusionis necessary to inferthatcompetition 6. Postscript on nullhypotheses causesand maintains an exclusivegeographic pattern. Therefore, evidenceon geographical patterns, perse, is Diamondand Gilpin(1982, 1983), Schoener(1982), no basisforinferring a roleforcompetition. and Harveyet al. (1983), laborto discredit theuse of 5) Failureto rejectthenullhypothesis ofindependent nullhypotheses inecology.Theyclaimthatnotonlyare speciesplacementdoes not constitute its acceptance, thosewe havediscussedaboveillconceived, weak,cirnordoes it implythatcompetition or anyothercausal cular,difficult to test,and of courseunsuccessful, but processesdo notoccur.It does implythatthereis no thatothernullhypotheses posedandtestedbyvarious evidencein thepatternof speciesco-occurrences, per authors(Connorand Simberloff 1978, Connorand se, thatcompelsone to positsomeeffect ofone species McCoy 1979, Stronget al. 1979, Simberloff and on anotherspecies'geography. Boecklen1981) are equallyreprehensible. By implica463 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions thevalueofthisvariablefor tionone couldadd to thislista growing bodyofsimilar ranges.We can determine of by an inspection of thisdisdain(Williams theobservedspecies'geographies literature equallydeserving thevalueofthis 1964, Poole and Rathcke1979, Ricklefsand Travis thedata.But,howcan we determine 1980,Rabinowitz et al. 1981,Dillon1981,Colemanet variableforthe"control"instancewherecompetition al. 1982, Malanson1982, DeVita et al. 1982, and has playedno role?Whatrangeof valuescouldthis of no importance? others).We, of course,believethatthesenullhypo- variableassume,werecompetition theseshavebeenuseful,startlingly informative, and,in This questionmustbe answeredin orderto testan indetertheroleofcompetition concerning specific instances, vindicated byfurther analysis (Strong hypothesis biogeography. and Simberloff 1981,Connoret al. 1983,Connorand mining We suggestthata nullhypothesis and a nullmodel, Simberloff 1983,Simberloff 1983). to generatetheexpecteddistributions ofthe We believeitwouldbe informative heretosetoutthe contrived underthenullhypothesis, can userolewe envision fornullhypotheses andourmotivation variableofinterest theroleofthe"control"in orderto forusingthemin ecologyand biogeography. Strong fullyapproximate involving evidence. non-experimental discussesthe virtuesof usingnull testanhypothesis (1980) similarly However,fromsuchan analysisone canconcludeonly in thesetwodisciplines. hypotheses In a strictstatistical biologiessufficeto sense a null hypothesis is an eitherthatspecies' independent It is merelya conjecture hypothesis of no effect. that explainthedataat hand,orthatsomeadditional causal in thedataat handwouldlead one to positan explanation mustbe invoked. Without further nothing evidence, otherthanchancefortheobservedresult. probablyof an experimental explanation nature,one can neither While a null hypothesisis not the only kind of eliminateany particular causal mechanism, nor conmechanism has operated. hypothesis thatcan serveas the"testedhypothesis", it cludethata particular is certainly themostcommoninconventional out thatwe have consisstatistical We concludeby pointing tently usednullmodelsas a meansto challengeinferusage. In experimental research,the resultsderivedfrom encesdrawnfromnon-experimental evidence.We feel ormanipulations treatments specific appliedto subjects thatthisistheproperandusefulrolefornullmodels.As are comparedwithuntreated or controlsubjects.The longas thepractice ofinferring causefromnon-experitestedhypothesis is usuallythe nullhypothesis toflourish of no mentalevidencecontinues amongecologists, difference betweentreatments and controls.Unfortu- thenwe expectnullmodelsalso to flourish. natelymuchecologicalresearchis non-experimental. Largesetsofobservations themorphology, concerning - We would like to thankGeorge Hornand resourceuse of Acknowledgements distribution, abundance, behavior, forhiscomments on thismanuscript andBetsyBlizard plantsand animalsare collectedprimarily fordescrip- berger forpreparing the figure.This researchwas supported by a tivepurposes, butare also examinedin reference to a grantfromtheAcademicComputing Centerof theUniv.of widearrayof ecologicaland evolutionary theories.If Virginia. ofthesedataarefoundtobe consisparticular portions tentwitha particular theory, thentheyare adducedas support forthattheory. onedoesnotaskif Traditionally somealternative theory might explaintheavailableevidenceequallywellor evenifthedata are statisticallyReferences withthetheory consistent theyare saidto support. Alatalo,R. V. andAlatalo,R. H. 1979.Resourcepartitioning Whyis thisso? Unlike in experimental research amonga flycatcher guildin Finland.- Oikos33: 46-54. wherean explicit"testedhypothesis" is evaluatedby Baker,R. J. and Genoways,H. H. 1978. Zoogeography of bats.- In: Gill,F. B. (ed.),Zoogeography inthe use of a variablewithknowndistributional properties, Antillean Caribbean: The1975LeidyMedalSymposium. Acad.Nat. in non-experimental research, thedistributional propSci. Philadelphia, pp. 53-97. ertiesofthevariableofinterest areoftenunknown. For Bishop,Y. M. M., Feinberg, S. E. and Holland,P. W. 1975. an examplewereturn againto dataon thegeographical Discretemultivariate - MIT analysis: theory andpractice. Press,Cambridge, MA USA. distribution ofspecies.Froman analysis ofthedistribuS. A. 1944.Foundations - Harper ofPlantGeography. tionofbirdsin theBismarck Islands,Diamond(1975) Cain, & Brothers, NewYork. developedhis "assemblyrules".These rulesstate,in Coen,L. D., Heck,K. L. andAbele,L. G. 1981.Experiments sum,thatcompetition is a majorforcedetermining the on competition andpredation amongshrimps ofseagrass. - Ecology62: 1484-1493. of speciesamongislands.The evidence arrangement B. D., Mares,M. A., Willig, M. R. andHsieh,Y. H. adducedin support ofthisidea is theobservedpattern Coleman, - Ecology 1982.Randomness, area,andspeciesrichness. ofwhichbirdspeciesareon whichislands.However,if 63: 1121-1133. is the"experimental competition effect" forwhichwe Connor,E. F. and McCoy,E. D. 1979. The statistics and - Am.Nat. 113: biologyofthespecies-area relationship. must test,to what "control"do we comparethe 791-833. observedspecies'geographies? How do we assesswhat - and D. 1978. Speciesnumberand composiSimberloff, effects competition has? tionalsimilarity of the Galapagosfloraand avifauna.The variableof interest is theexclusivity of species' Ecol. Monogr.48: 219-248. 464 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions D. 1979. The assembly of speciescom- Nevo,E. G., Gorman, - and Simberloff, M., Soule',M.,Yang,S. Y., Clover,R. and Jovanovic, V. 1972. Competitive exclusionbetween munities:chance or competition?- Ecology 60: insularLacertaspecies(Sauria,Lacertidae):noteson ex1132-1140. - Oecologia (Berl.) 10: - andSimberloff, D. 1983.Neutralmodelsofspecies'co-ocperimentalintroductions. D. R., Simberloff, D. and - In: Strong, 123-190. currence patterns. conceptual Pielou,D. P. and Pielou,E. C. 1968. Associationamong Abele,L. G. (eds.), Ecologicalcommunities: Univ.Press:Princeton, speciesof infrequent occurrence: the insectand spider issuesandtheevidence.Princeton faunaofPolyporus betulinis NJ,USA. (in press). (Bouliard)Fries.- J.Theor. -, McCoy,E. D. andCosby,B. J.1983.ModeldiscriminaBiol. 21: 202-216. studies.tionand expectedslopevaluesin species-area Poole,R. W. and Rathcke,B. J. 1979. Regularity, random- Science Am.Nat. 122 (in press). inflowering ness,andaggregation phenologies. andniche 203: 470-471. Crowell,K. L. andPimm,S. L. 1976.Competition ontosmallislands.- Oikos27: Rabinowitz, D., Rapp, J. K., Sork,V. L., Rathcke,B. J., shifts ofmiceintroduced 251-258. Reese,G. A. andWeaver,J.C. 1981.Phenological propdisthegeographical P. S. 1957. Zoogeography: erties of wind-and-insect-pollinated Darlington, prairieplants.ofanimals.- Wiley,NewYork. Ecology62: 49-56. tribution encounter Raup,D. M. and Crick,R. E. 1979. Measurement DeVita,J.,Kelly,D. andPayne,S. 1982.Arthropod offaunal - J.Paleontol. inpaleontology. rate:a nullmodelbasedon randommotion.- Am.Nat. similarity 53: 1213-1227. 119: 499-510. Ricklefs, R. E. andTravis,J.1980.A morphological approach - In: ofspeciescommunities. - Auk 97: to thestudyofaviancommunity Diamond,J.M. 1975.Assembly organization. 321-338. Cody,M. L. and Diamond,J. M. (eds.), Ecologyand HarvardUniv. Press,Cam- Root,R. 1967.Thenicheexploitation evolutionof communities. oftheblue-gray pattern - Ecol. Monogr.37: 317-350. gnatcatcher. MA, USA, pp. 342-444. bridge, of interspecificSchoener,T. W. 1982. The controversy - 1978. Niche shiftsand the rediscovery over interspecific - Am.Sci. 66: 322-331. - Am.Sci. 70: 586-595. competiton. competition. M. E. 1982.Examination ofthe"Null"model Simberloff, - andGilpin, D. 1978.Usingislandbiogeographic distributions on forspeciesco-occurrences - Am.Nat.112: of Connorand Simberloff to determine ifcolonization is stochastic. islands.- Oecologia(Berl.)52: 64-74. 713-726. on - 1983. Properties - and Gilpin,M. E. 1983. Are speciesco-occurrences of coexisting birdspeciesin two arusefulin and are null hypotheses islandsnon-random, chipelagoes.- In: Strong,D. R., Simberloff, D., and D. community ecology.- In: Strong,D. R., Simberloff, Abele,L. G., (eds.),Ecologicalcommunities: conceptual concepandAbele,L. G. (eds.),Ecologicalcommunities: issuesandtheevidence.Princeton Univ.Press,Princeton, tual issues and the evidence.PrincetonUniv. Press, NJ,USA, (in press). - andBoecklen,W. 1981.SantaRosaliareconsidered: Princeton, NJ,USA (in press). size - Evolution in themorphology anddistribuDillon,R. T. 1981.Patterns ratiosandcompetition. 35: 1206-1228. in OneidaLake, New York,detected - andConnor, tionof gastropods E. F. 1979.Q-ModeandR-Modeanalyses of - Am. Nat. nullhypotheses. usingcomputer-generated biogeographic distributions: Null hypotheses based on - In: Patil,G. P. andRosenzweig, 118: 83-101. random colonization. M. and Dueser,R. D. and Hallett,J. G. 1980. Competition L. (eds.),Contemporary quantitative ecologyand related in a forestfloorsmallmammalfauna.habitatselection ecometrics. Int.Co-operative Publ.House,Burtonsville, Oikos35: 293-297. MD, USA, pp. 123-138. of a tropicalguildof nec- - andConnor,E. F. 1981. Missingspeciescombinations. P. 1976. Organization Feinsinger, tivorous birds.- Ecol. Monogr.46: 257-291. Am.Nat. 118: 215-239. - Synthese Gilpin,M. E. andDiamond,J.M. 1982.FactorscontributingStrong, D. R. 1980.Nullhypotheses inecology. 43: inspeciesco-occurrences on islands.to non-randomness 271-285. Oecologia(Berl.)52: 75-84. -, Szyska,L. A. and Simberloff, D. 1979. Testsof comcompetition, Grant,P. R. and Abbott,I. 1980. Interspecific munity-widecharacter displacementagainst null 34: islandbiogeography, andnullhypotheses.Evolution - Evolution33: 897-913. hypotheses. 332-341. - and Simberloff, D. S. 1981. Straining at gnatsand swal- Evolution35: Harper,C. W. 1978. Groupingsby localityin community lowingratios:Characterdisplacement. - Lethaia testsofsignificance. ecologyandpaleoecology: 810-812. 11: 251-257. J. 1971. Distribution Terborgh, on environmental gradients: J.G. andMay,R. Harvey,P. H., Colwell,R. W.,Silvertown, Theoryand a preliminary interpretation of distributional M. 1983.Nullmodelsinecology. Ann.Rev.Ecol. Syst. in the avifaunaof the Cordillera, patterns Vilcabamba, (in press). Peru.- Ecology52: 23-40. analysis ofdis- - and Weske,J. S. 1975. The role of competition Krebs,C. J.1978.Ecology:The experimental in the - HarperandRow,NewYork. tribution andabundance. distribution ofAndeanbirds.- Ecology56: 562-575. gardens:ef- Vuilleumier, ofhanging Malanson,G. P. 1982.The assembly F. andSimberloff, D. 1980.Ecologyversushis- Am.Nat.119:145-150. fectsofage,area,andlocation. toryas determinants ofpatchy andinsulardistributions in D. S. 1980.The use of nearest Meagher,T. T. and Burdick, highAndeanbirds. In: Hecht,M. K., Steere,W. C. and analysesin studiesof association. frequency neighbor Wallace,B. (eds.),Evolutionary vol. 12. Plenum biology, Ecology61: 1253-1255. Press,NewYork,pp. 235-379. in desert Williams, Munger, J.C. and Brown,J.H. 1981.Competition C. B. 1964. Patterns in the balanceof nature.rodents:an experiment exclosures. withsemipermeable AcademicPress,London. Science211: 510-512. H. M. 1972.Competition, Wilbur, predation, andthestructure - Ranasylvatica - Ecology studiesof microcrustacean oftheAmbystoma Neill,W. E. 1975. Experimental community. of and efficiency community composition competition, 53: 3-21. - Ecology56: 809-826. resourceutilization. S. J.andBiehl,C. C. 1982.Islandbiogeographic Wright, distributions: testingforrandomregular,and aggregated - Am.Nat.119: 345-357. ofspeciesoccurrence. patterns 465 OIKOS 41:3 (1983) This content downloaded on Thu, 21 Feb 2013 12:18:56 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions