* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

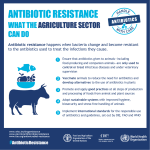

Download Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance

Reproductive health wikipedia , lookup

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Patient safety wikipedia , lookup

Medical ethics wikipedia , lookup

Race and health wikipedia , lookup

Health equity wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Antimicrobial resistance wikipedia , lookup