* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download extreme age as functional immunosuppression?

Patient safety wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

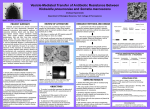

Multiple sclerosis research wikipedia , lookup

Age and Ageing 2013; 42: 266–268 © The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Geriatrics Society. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs198 All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: [email protected] Published electronically 11 January 2013 CASE REPORT A case of necrotising fasciitis caused by Serratia marsescens: extreme age as functional immunosuppression? THOMAS EDMUND COPE1, WEI COPE2, DAVID MARTIN BEAUMONT3 1 Auditory Group, Newcastle University, Institute of Neuroscience, Medical School, Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear NE1 4LP, UK 2 Histopathology, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear NE1 4LP, UK 3 Elderly Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead, Tyne and Wear NE9 6SX, UK Address correspondence to: T. E. Cope. Tel: (+44) 191 222 3445. Email: [email protected] Abstract We report the case of a 97-year-old woman who had a prolonged hospital admission for the treatment of right-sided heart failure. During her stay she experienced a rapid deterioration, characterised by shortness of breath, cardiovascular compromise and a hot, red, swollen calf. Post-mortem examination demonstrated that this was caused by necrotising fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens as a single pathogen. This is only the second reported case of this condition in the absence of diabetes or immunosuppression, and clinical deterioration was much more rapid. The case underlines the importance of circumspection and regular review in the diagnosis of the elderly patient. It reminds us that these patients should be viewed as functionally immunosuppressed, and that some or all of the haematological markers of infection can be absent even in severe disease. Keywords: gerontology, immunocompromised patient, fascitis, necrotising, Serratia, older people Case report A 97-year-old woman was admitted to our elderly care ward following a fall. Her background included vascular dementia, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease stage 3 (estimated glomerular filtration rate of 35 ml/min) and right-sided heart failure, with preserved left ventricular function. On examination, significant peripheral oedema, bibasal pleural effusions and an elevated jugular venous pressure were noted. Her records revealed that she had gained 24 kg since her admission to residential care 5 months previously. Diuretic therapy was introduced but, despite escalating treatment to combination furosemide and metalozone, only 2 kg of weight loss was achieved over 3 weeks. At 02:00 on the 21st day of her inpatient stay, the patient was reviewed by the medical team as she was complaining of leg pain. No abnormality was detected on examination, 266 but early abnormalities are likely to have been obscured by marked peripheral oedema. At 10:00 the patient was newly tachypnoeic (respiratory rate 25), hypotensive (BP 81/56) and had oxygen saturations of 81% on air (98% with 3l/min oxygen delivered through nasal cannulae). Her right leg was noted to be mildly erythematous, and more swollen than her left. A clinical diagnosis was made of deep vein thrombosis with pulmonary embolus and therapeutic-dose low molecular weight heparin was administered. Her D-Dimer was measured to be 1,192 ng/ml, and CT pulmonary angiography was requested. Her C-reactive protein (CRP) was noted to have increased to 157 mg/l, from 31 mg/L the previous day, but her neutrophil count was only 2.7 × 109/l. At the time, this was thought to be in keeping with the clinical diagnosis as CRP is commonly elevated in pulmonary embolism, and some have suggested its use as a biomarker; however, this rise is rarely to levels >85 mg/l [1]. Similarly, elderly individuals are known to have an impaired neutrophil response [2], and infection should still be suspected in this A case of necrotising fasciitis caused by Serratia marsescens Figure 1. (A) (haematoxylin and eosin stained, ×2 magnification): there is an extensive neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis, with extensive tissue necrosis. (B) (Haematoxylin and eosin stained, ×10 magnification): inflammatory infiltrate can be seen among adipocytes within the subcutis. (C and D) (Gram stained, ×40 magnification): there are numerous, monomorphic, Gram-negative bacilli throughout dermis and involving subcutis. context. At 16:00 her right calf appeared engorged and dusky, but the extent of discolouration had not changed and the foot was spared. At 20:30 her calf was erythematous, warm, sloughy and blackened. The patient was now unresponsive. Her CRP at this time was 207 mg/l, neutrophils 3.6 × 109/l, prothrombin time 22 s, venous pH 7.14 and lactate 9.8 mmol/l. The diagnosis was revisited, and intravenous flucloxacillin and amoxicillin were administered. Unfortunately the patient suffered a cardiac arrest and passed away at 22:24. Post-mortem examination was performed to determine the cause of death. No significant thrombi were identified in the pulmonary arteries or leg veins. Histological examination of the right leg showed acute inflammation with extensive necrosis involving skin and subcutis, including superficial fascia, consistent with necrotising fasciitis (see Figure 1). Microbiological swabs taken from the affected area resulted in the growth of Serratia marcescens as a single pathogen. Owing to the infrequency of this organism as causative in this context, paraffin embedded samples were cut from the fascial layer for 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. This analysis confirmed the presence of a single ribosomal DNA sequence, which demonstrated >99% homology with S. marcescens. As can be seen in the figure, numerous, monomorphic, Gram-negative bacilli were present throughout the dermis and involving subcutis, but solely scanty, Gram-positive bacilli were seen on the skin surface (not shown). This pattern would contamination. be inconsistent with post-mortem Discussion S. marcescens is a Gram-negative bacterium from the enterobacteriaceae family. It is ubiquitous in the environment, especially in damp conditions, but can be an opportunistic pathogen, most frequently in the respiratory and urinary tracts of hospitalised patients [3]. Soft tissue infection by S. marcescens is rare, and typically occurs in immunocompromised individuals with diabetes, malignancy, steroid use or renal failure [4]. It can be responsible for necrotising fasciitis as a single pathogen [5], but only one other case has been reported in the absence of diabetes or immunosuppression [6]. In this case, the evolution from first symptoms to overt necrotisation was much slower, occurring over 4 days. When it does occur, S. marcescens soft tissue infection carries a high mortality, in part because of co-morbidity but also because the antibiotics frequently given to treat cellulitis are typically ineffective. The antimicrobial therapy administered in this case was in accordance with local policy, but would have provided poor coverage against those Gram-negative or methicillinresistant pathogens that can be acquired in hospital, and would certainly have been ineffective against S. marcescens. In unwell, elderly patients the risks of antibiotic-associated 267 T. E. Cope et al. diarrhoea must be balanced against the benefits of broader spectrum antimicrobial therapy on an individual basis. We propose that, despite the relatively benign pathogen, disease progression was rapid in this case because of the functional immunosuppression of extreme age. It is often clinically overlooked that there is a decline in the speed and efficacy of immune response with increasing age, which is independent of the level of co-morbidity [7]. These effects are even more pronounced if they are accompanied by a poor nutritional status [8]. This case underlines the importance of circumspection and regular review in the diagnosis of the elderly patient. It reminds us that these patients should be viewed as functionally immunosuppressed. The failure of this woman to mount a neutrophilic response to life-threatening bacterial infection further demonstrates that some or all of the haematological markers of infection can be absent even in severe disease. Key points • Extreme age is a form of immunosuppression. • Haematological markers of infection can be absent in severe disease. • ‘Benign’ pathogens can present aggressively and atypically in the elderly. Acknowledgements We are indebted to Prof. Kate Gould, consultant microbiologist at the Freeman Hospital in Newcastle upon Tyne, for her microbiological advice and confirmatory testing, and to Dr Tuomo Polvikoski, consultant histopathologist at 268 the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle upon Tyne, for his assistance with the interpretation of post-mortem findings. Conflicts of interest None declared. References 1. Ohigashi H, Haraguchi G, Yoshikawa S et al. Comparison of biomarkers for predicting disease severity and long-term respiratory prognosis in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Int Heart J 2010; 51: 416–20. 2. Schroder AK, Rink L. Neutrophil immunity of the elderly. Mech Ageing Dev 2003; 124: 419–25. 3. Hejazi A, Falkiner FR. Serratia marcescens. J Medi Microbiol 1997; 46: 903–12. 4. Crum NF, Wallace MR. Serratia marcescens Cellulitis: a case report and review of the literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2002; 11: 550–4. 5. Zipper RP, Bustamante MA, Khatib R. Serratia marcescens: a single pathogen in necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 23: 648–9. 6. Rimailho A, Riou B, Richard C, Auzepy P. Fulminant necrotizing fasciitis and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Infect Dis 1987; 155: 143–6. 7. Oyeyinka GO. Age and sex differences in immunocompetence. Gerontology 1984; 30: 188–95. 8. Roebothan BV, Chandra RK. Relationship between nutritional status and immune function of elderly people. Age Ageing 1994; 23: 49–53. Received 28 August 2012; accepted in revised form 21 November 2012