* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Outline, First Exam

Separation of powers under the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Separation of powers in Singapore wikipedia , lookup

Head of state wikipedia , lookup

Politics of Argentina wikipedia , lookup

Congress of Colombia wikipedia , lookup

Separation of powers wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of Venezuela wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of democracy wikipedia , lookup

History of democracy wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of Hungary wikipedia , lookup

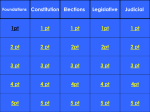

Dale Story POLS 2311 CLASS OUTLINE--FIRST EXAM I. INTRODUCTION a. Approach of the course i. Comparative: will examine the U.S. system along with other systems ii. Critical analysis: will expose students to diverse perspectives, including those that are quite critical iii. Political economy: recognizes the juxtaposition of the economic sphere and the political sphere iv. Focus on policies & current events: we will look at outcomes and significant events that are happening currently b. Politics and political culture i. Politics includes power, influence, legitimacy, authority, rewards (who gets what, when, how). Political power = monopoly of violence? ii. Political culture is the basic orientation of the citizens toward their political system. In the U.S., this is a general consensus on the abstract principles of democracy (this country is a democracy and the citizens prefer that). But reservations are found on specific and concrete issues. The elites have a broader commitment to concrete manifestations of democracy than do the masses. c. Three perspectives on division of power i. Democracy 1. Definition: popular sovereignty, political equality, popular consultation, and majority rule (with minority rights) 2. Prerequisites for democracy: education and income (individual and aggregate levels) 3. Examples of repression and/or lack of democracy a. 3/5th Compromise b. Slavery c. Electoral College? d. Lack of universal suffrage e. Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 f. Lincoln’s suspension of due process and use of military law g. “Red scare” roundup (1919-20) of suspected Bolsheviks h. Japanese-American internment in World War II i. McCarthyism in the 1950s ii. Elitism 1. Defining aspects a. Society is divided between elites and masses b. Elites are few and dominate power c. Policies reflect elite values d. Elites share a broad consensus on major issues and values. Disagreement occurs only on minor issues. e. Mobility is slow at best f. Big business is most important interest group g. Public pressure is seldom successful 2. Michel’s iron law of oligarchy. All political organizations result in a self-perpetuating elite. Even the most allegedly democratic and/or those representing the underprivileged are prone to elite dominance 3. Mill’s power elite a. Three levels of power: power elite, middle levels, and masses. b. Critical decisions are made by power elite composed of top political officials, top corporate executives, and the military leaders. c. These three spheres are interlocked in four ways: shared objectives, overlapping career patterns, similar economic and educational origins, and social interactions. 4. Evolution of U.S. elites 1 II. a. Hamilton and the Federalists--Secretary of Treasury under Washington—statute at Dept. of Treasury—favored central government and aided business— stimulated commerce and industrial growth—through 1810. b. Jefferson and the Anti-federalists (Democratic-Republican)—Southern planters, landowners, and local elites opposed Hamilton’s strong, central government— Titular head was Thomas Jefferson (elected President in 1809). God forbid we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion. Through 1820s. c. Rise of Western elites—Personified by President Andrew Jackson. Social mobility. New elites. Emphasis on self-determination and individual initiative. Harbinger of manifest destiny and the westward expansion. Favored abolition of the Electoral College. Through 1860s. d. Elite cleavage—Civil War. Greatest division between elites in U.S. history. Much more than slavery. Northern elites were merchants and industrialists who wanted free labor (mobile and contractual) and protective tariffs (to protect the new domestic industries). Southern landowners and plantation owners were dependent on slave labor (tied to the plantation) and free trade (exports of cotton, etc.) Future of the West. Secession and “states’ rights.” Through late 1800s. e. New industrial elites—Social Darwinism, entrepreneurs, and the masses. Survival of the fittest. Period of greatest dominance of big business. Industrial revolution. High tariffs and less government regulation. f. Liberal establishment 5. Positions of power a. Governing elites i. Yale, Harvard, Columbia ii. Prestigious law firms iii. Prior administrations iv. Executives of GM, Ford, Merrill-Lynch, Goldman-Sachs, etc. b. Corporate elites i. WalMart has annual revenues greater than 90% of the countries in the world. 100 corporations control over 50% of industrial assets—top 5 control 10%. 50 banks control almost 50% of banking assets (most in New York). Petroleum companies well-represented in top 50. iii. Pluralism 1. Defining aspects: policies result from bargaining and compromise; elite competition (countervailing centers of power); citizens exert influence by choosing among competing elites in elections; multiplicity of groups; no single elite dominates 2. Differs from Democracy: decisions made by elite interaction (not individual participation); tendency toward oligarchy; key political actors are leaders or organizations (not individuals). 3. Differs from Elitism: competition among elites; bargaining and compromise; choices in elections, multiplicity of groups. POLITICAL ECONOMY a. Interrelations between politics and economics—politics affects economics (most political decisions and policies are focused on economic outcomes), and economics affects politics (success or failure in elections) b. Capitalism i. Five characteristics: industrial; market economy; wage labor; profit orientation; periodic crises ii. Capitalism as an ideology—accepted as a given; anti-capitalism, socialism, communism, and the like are rejected automatically. c. U.S. political economy i. MNCs and large banks—few in number, but each entity accounts for a disproportionate slice of assets, profits, etc.; larger than some nation-states; global; lack of competition (lack of risk); concentrated in key sectors; very cooperative 1. Fortune 500, by revenues—for comparison, the average Gross National Income (World Bank data) for over 170 of the most significant countries in the world is $343,103 mn. 2 III. Thus, both Exxon and Walmart have higher annual revenues than half the countries in the world. 2. World top 100 ii. Competitive sector—much larger in number, but smaller in size of each establishment; fragmented and relatively powerless; government regulations can be oppressive; real competition and real risk iii. State as economic actor—not through nationalizations (state ownership of productive enterprises), but through enormous government spending and regulatory policies. CONSTITUTION AND FEDERALISM a. Purpose of a constitution—basic groundwork, rules of the game, basic structure, not easily altered, not policy-making—U.S. Constitution vis-à-vis Texas Constitution(http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/ and http://www.tlc.state.tx.us/pubsconamend/constamend1876.pdf) b. Articles of Confederation i. Drafted in 1776—tied together the charters of the original colonies—ratified by all states in 1781—each state assured its sovereignty and independence—each state had the powers to regulate commerce and levy taxes ii. Three basic philosophies 1. The Articles of Confederation were a reflection of a Confederate separation of powers among local and national governments—very little power to the national government and most power decentralized in each of the states 2. A Unitary system is the exact opposite. Essentially a single national government with little power granted to the states. 3. A Federal system is one with shared and roughly equal between the levels of government. Equity, cooperation, and overlap exist. iii. Failure—began to fail around 1783. 1. Inability of the National Congress to levy taxes—could not raise the revenue pay the public securities that had financed the Revolution. 2. Could not regulate interstate commerce—interstate tariffs created havoc among commercial interests. 3. State governments were a threat to creditors and investors due to the power of states to issue cheap paper money 4. The national government could not raise a sufficiently strong military to deal with such events as Shay’s Rebellion, ousting the British from the northwest, protecting settlers from indigenous populations, piracy, and smuggling. 5. National government could not provide the protectionist policies necessary to shield U.S. infant industries from British imports. c. Constitutional Convention i. Economic conference in 1786—general economic conference of all states in Annapolis to discuss the economic problems with the Articles. The delegates called for a new convention in 1787 to revise the Articles. The call was confirmed by Congress, and 55 delegates met in the spring and summer of 1787 in Philadelphia. However, the Convention discarded its mandate simply to revise the Articles—they proceeded to write a complete new constitution. ii. Constitutional compromise (Great Compromise or Connecticut Compromise). The Convention was divided between the Virginia Plan (“Large States” Plan) and the New Jersey Plan (“Small States” Plan). The former advocated representation in Congress apportioned by population, i.e., the large states (most populous states) would have more representatives than smaller states. The latter advocated representation in Congress apportioned equally by states, i.e, all states (whether large or small, in terms of population) would have the same number of representatives. The Great Compromise was to create a bicameral legislature (two chambers), with the Senate providing for equal representation for each state and the House of Representatives providing for representation according to population. iii. Other compromises 1. Slavery compromise. Slaveholders (in the South) wanted to count slaves for purposes of representation; while non-slaveholders (in the North) wanted to count slaves for purposes of taxation. The compromise was to count slaves as 3/5th of a person for purposes of both 3 representation and taxation. While the issue of slavery and the slave trade was hotly debated, no decision was taken to prohibit slavery immediately (at least not prior to 1808). 2. Export tax compromise. While the South did agree to an import tax on slaves, there was no agreement on an export tax (which would have benefited the North and harmed the South) 3. Suffrage. No property qualifications appear in the Constitution, though Convention delegates generally favored one. The decision was left to the states, who generally only granted the right to vote to white males who were landowners. iv. Constitutional framework. First three articles discuss the three branches of government separately. The next four articles discuss the powers of the states, amending the Constitution, “Supreme Law of the Land,” and ratification. The first ten Amendments (the “Bill of Rights”) essentially were a quid-pro-quo of the ratification. The Constitution has a total of 27 Amendments. v. Undemocratic elements of Constitution 1. Slavery and 3/5th Compromise (though in many ways the framers of the Constitution did intend to protect minority rights and individual liberties from any potential oppression of majority rule). 2. Of the 4 major decision-making bodies (House, Senate, President, and Supreme Court), only the House members were elected “democratically” (direct, popular election). Senators by state legislatures. President by electors selected by state legislatures. Supreme Court appointed by President (subject to Senate confirmation). 3. Charles Beard, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. 4. “Economic Interests and the American Constitution: A Quantitative Rehabilitation of Charles A. Beard,” by Robert A. McGuire and Robert L. Ohsfeldt. vi. Ratification. Ratified by all states in 1789. New York, Massachusetts, and Virginia were holdouts. The Anti-Federalists charged that the Constitution was aristocratic, monarchical, and undemocratic. The major criticism was the lack of a “Bill of Rights,” which confirmed suspicions that the Founding Fathers were more concerned with protecting property than preserving individual liberty. The three holdout states insisted that a Bill of Rights be added as amendments. This was done (first Ten Amendments) immediately after ratification. Essentially, the Bill of Rights was required for ratification. Another important contributor to the ratification of the Constitution was the Federalist Papers. These were addressed to the people of the state of New York and published in various New York city newspapers. They totaled 85 essays that defended the proposed constitution and explained its provisions in detail. d. Parliamentary alternatives to separation of powers—basically a fusion of executive and legislative powers i. British model. Parliamentary majority picks the Prime Minister and can remove him/her. The Prime Minister is usually the head of the majority party. The Cabinet is picked by the Prime Minister from Parliament. Party discipline insures voting support for the policies of the Prime Minister. The House of Commons has weekly access to questioning the Cabinet and even the Prime Minister. Possible advantages. Vote of confidence (or no confidence) provide an early and parliamentary means for removing a Prime Minister (actually calling for new elections). More accountability. The executive and legislative branches must work together as a team. e. Judicial interpretations of Constitutional powers (economic regulation) i. Broad powers—early-1800s—McCulloch v. Md. (1819), Chief Justice John Marshall led the majority who legitimated the creation of a national bank (under the implied powers clause— anything “necessary and proper” for carrying out expressed powers). Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), recognized the power to regulate coastal shipping as part of the power to regulate interstate commerce. ii. Constrained powers—late-1800s—Lochner v NY (1905), New York tried to regulate a 60 hour work week for bakers. But the Court said this interfered with the liberty of contract—the laissez faire principle of establishing criteria for employment according to the free market. The state could not interfere with liberty of contract. Oliver Wendell Holmes issues a famous dissent stating that the Constitution does not enforce laissez faire economics 4 IV. iii. Broad powers—1930s—Nebbia v NY (1934), upheld the right to regulate prices. Upheld the Holmes dissent in 1905 f. U.S. Federalism i. Belief in local government? Many profess a greater affinity for local government (or, at least, a greater disdain for national government). However, the reality is that we know more about national government and participate at much higher levels in national elections. ii. Size of state and local governments. The powers of state and local governments have been expanding at a more rapid rate than those of the national government—though the national government still often attaches “strings” to federal aid to the states. iii. Assessments of Federalism 1. Racism. States’ Rights. Slavery. Discrimination. Segregation. Separate “but equal.” Example: Who enforced the integration of Little Rock Central High School (among others)? George Wallace. Oxford, Mississippi. 2. State ineptness. Meets how often? Weak governors? Inappropriate Constitutions? Lessthan-quality representatives? Corruption? Competition and inequalities among states? Lack of equity among states? 3. Advantages. Greater voice. More remedies. Economies of scale. Government officials not overloaded. 4. Disadvantages. Conflict. Complexity. Stalemate. Duplication IDEOLOGY AND PUBLIC OPINION a. Role of the Media i. Concentrated ownership. Almost half of the 50 major U.S. cities do not have two competitive newspapers. Dominated by giant conglomerates: http://www.freepress.net/ownership/chart/main; http://www.freepress.net/ownership/chart/main; http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3677/is_199801/ai_n8772979/; http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_7644/is_200904/ai_n53077114/?tag=rel.res1; http://www.mcclatchydc.com/184; http://www.belo.com/companies/; ii. Media bias. TV: traditional networks, CNN, Fox, MSNBC. Editorials: talk radio, TV “pointcounterpoint,” taking sides, hyperbole. TV entertainment: culture shocks. Newspapers: overwhelmingly conservative. Movies? Music? iii. Selective perception. We see what we want to see. Scenes of conditions in low-income neighborhoods create more prejudice towards minorities than raising social consciousness. Archie Bunker was intended as a caricature of sexism, racism, homo-phobia, etc. But the public adopted him as an iconic figure—OK to have discriminatory attitudes. b. Public opinion i. Areas: political system; groups; leaders; and policies ii. Functions: psychic; social; economic iii. Measures: polls (scientific?); individuals, “panel” studies; ELECTIONS iv. Dimensions: direction and intensity v. Forming an opinion and potential departure points. Formed early in life—reflections of our parents. 1. Parental rebellion 2. Civic education 3. Peer groups 4. Social/economic mobility 5. Marriage 6. Maturation vi. Group influence 1. Reference groups (interest groups) 2. Primary groups—frequent and direct contact 3. Categoric groups—demographics c. Impact of public opinion i. Rarely shapes elite behavior 1. Absence of public opinion 2. Instability of public opinion 5 V. 3. No clear perception of public opinion—difficult to know ii. Little elite response. Policies change when elite opinion shifts, not when the opinions of the masses shifts. Civil rights and Vietnam War. Negative opinion most effective—voting against someone. iii. Manipulation of public opinion. Sound bites; Media Opportunities; October Surprise; “Wag the Dog.” PARTICIPATION AND ELECTIONS a. Political participation i. Forms: Legitimate, Non-traditional, Extra-legal ii. Actual levels: Presidential elections (60%), Off-year elections (40%), State elections (30%), and Local elections (anywhere from 10-30%). iii. Historical barriers to participation: Lack of universal suffrage for many decades, literacy requirements, poll tax. iv. Current barrier to participation? Registration v. Reforms to increase participation: Open registration, Elections on Sundays or holidays b. Elections i. Elections are not policy mandates: no clear policy alternatives, voters unconcerned with policy, elected officials not bound by campaign pledges. ii. Functions of elections: symbolic reassurance, select personnel (not policy), retrospective judgments, protection against official abuse iii. Three types of presidential elections: Sustaining (continues dominant coalition), Deviating (temporarily deviates), Critical (qualitative change). Today: “shared” government? iv. Three stages of presidential elections: pre-convention, convention, post-convention (general election 1. Party Conventions a. Larry Sabato on purpose b. Candy Crowley on general introduction v. Electoral reforms to combat corruption: Limits on campaign contributions; Disclosure requirements; public financing for presidential elections (opt out?). vi. Citizens United-- 6