* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CLAS 201 (Hellenism and Philosophy)

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

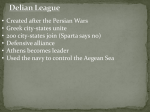

CLAS 201 (Hellenism) PELOPONNESIAN WAR (continued) When we last left off, the Athenians had suffered a terrible defeat in Sicily. This setback encouraged the Spartans to break the 30 Years Peace. The purpose of the Athenian expedition had been to conquer Sicily with a view to attacking Sparta down the road, so the Spartans had good reason to re-engage the Athenians. In 413, therefore, King Agis invaded Attica with an army of hoplites. Instead of retreating after a couple of weeks, however, he stationed a permanent garrison at the fortress of Decelea (just as Acibiades had proposed). This garrison kept the Athenians penned up in the city. In 412 Alcibiades switched sides again. He had been conducting an affair with King Agis‟ wife and, in a word, Sparta was not a good place to be. He joined the Athenian fleet operating in the Aegean (but did not dare to return to Athens itself, not yet at least). He was responsible for the naval victory at Cynossema. In 411, Thucydides‟ account ends and we have to rely on other sources, among them Xenophon‟s Hellenica. At the same time Aristophanes tells us something about the war, indirectly, through his comedies. His Lysistrata is based on the premise that the Athenian women will not sleep with their husbands until they stop this pointless war with the Spartans; similarly the Spartan wives do the same. In the Acharnians, Dikaiopolis („Just City‟) make shis own private peace with Sparta and, as a result, his own farm flourishes and he lives a life of leisure, even as the Athenians continue to war and do without. In 410 Alcibiades won another victory at Cyzicus. Sparta offered to end the war, but the Athenians (who had caught their breath by now after the Sicilian disaster) refused. Both the Athenians and the Spartans were vying for financial support from the Persians. Jumping forward several years, in 407 Lysander (a Spartan general) comes to the fore. At the same time Alcibiades returns to Athens and is appointed commander in chief of all forces. In 406 the sea battle of Arginusae is fought. Slaves were offered their freedom if they would loyally row for Athens. In the end, the Athenians scored an impressive victory. Unfortunately, the weather was bad and prevented the fleet from rescuing the ship wrecked and retrieving the dead. For this neglect, six generals were put on trial simultaneously, found guilty and executed. Another two fled and passed their lives in exile. While the Spartans had suffered a reverse because of this battle, they received money from the Persians to rebuild their fleet. Lysander took charge of it. In 405 the sea battle of Aegospotamoi was fought. The Athenians suffered a comprehensive defeat – 150 ships were either destroyed or captured. Furthermore, this defeat interrupted the steady supply of grain from the Hellespont region to Athens. The war was effectively over. Over the succeeding months, Lysander sailed the Aegean, peeling Athens‟ former allies away. Athens itself was blockaded by land and sea. At last it surrendered. Terms of Surrender Some of Sparta‟s allies argued for the city‟s destruction. Sparta decided to be merciful – it was aware that it would be fighting some of its allies down the road and knew that Athens could be an ally in such wars (such was the fickleness of greek alliances). The terms of surrender were harsh nonetheless. The long walls were pulled down, as well as the walls surrounding the city. The fleet was reduced to a mere 12 ships. All its former subjects/allies were now free and independent. Their overseas possession were stripped from the. The city was now subordinate to Sparta‟s will; indeed, 30 tyrants (oligarchs) were put in charge of the state on behalf of the Spartans. The population was depleted. The war had killed off half its male citizens. TERMS Delian League (477), Delos, Apollo, Pausanias, Themistocles, Cimon, Eurymedon (463), Aristides, Hellenotamiae, Carystus, Naxos, Thasos, Cleruchy (colony/garrison), Long Walls, 30 Years Peace (445), Peloponnesian War, Thucydides, realist/pragmatist, Epidamnus, Corcyra, Corinth, Potidaea, Megara, Megaran Decrees, Archidamus, Pericles, Plague, Cleon, Mytilene, Pylos, Sphacteria, Brasidas, Nicias, Peace of Nicias (421), Alcibiades, Melos, Melian Dialogue, Sicily, Lamarchus, Herms, Egesta, Syracuse, Gylippus, Demosthenes, Decelea, King Agis, Eclipse, Lysander, Cynossema, Cyzicus, Arginusae, Aegospotamoi, terms of surrender, 30 tyrants TRIAL OF SOCRATES In 399, the philosopher Socrates was put on trial – the trial itself is reported in Plato‟s Apology. He was charged with corrupting the young and introducing foreign gods into Athens – capital subject to the death penalty. He was ultimately found guilty and put to death – by being forced to drink hemlock. The trial and death of Socrates has been seen (by later commentators) as a martyrdom of a man who believed in freedom of speech and the free exercise of his intellect. In another dialogue associated with the trial (the Crito), Plato has Socrates deliver a famous last speech while in prison. After being advised by his student Crito to quit the city and escape to a city where he won‟t be returned to Atherns, Socrates says he cannot do any such thing because such an action would be unconscionable for a true philosopher. As admirable as Socrates was, there are a couple of points we might want to consider. The charges brought against him were, all things considered, a bit trumped up. But his prosecutors did have a legitimate beef against him. First, as we saw, Athens was in state of political tension: the democratic faction had all but recently ousted the oligarchic one with violent results for both populations. Among Socrates‟ students could be counted Alcibiades and Critias, both hard-lined oligarchs at one time or another; indeed, Critias was a primary member of the Thirty. At the same time the democrats would remember that Socrates had refused to play ball with them back in 406/05. In the wake of the Battle of Arginusae, the dead and shipwrecked survivors hadn‟t been rescued due to inclement weather. Six of eight generals had been tried en masse and executed. Socrates (who had been on the prytanis at the time) had advised that it was illegal to try all general together. When the prytanis and Boule refused to consider his opinion, he had gone home. Because the prosecutors of the generals had been democrats, they hadn‟t taken well to Socrates‟ abstention. Most damning, perhaps, were Socrates‟ pro-Spartan views. His ideal city, as described in the Republic, bore many similarities with Sparta. In other words, he and his students seemed to be sympathizers of the Spartan way of life – in a time of war! He himself was not a great admirer of freedom of speech and was probably not in a position to complain that the city‟s government was putting him on trial for his outspoken views. Whether Socrates was guilty or not, he might have avoided death had he not insulted the jury. He was found guilty. The sentence was death, unless he proposed a reasonable alternative, exile or a hefty fine. He proposed instead a ridiculously paltry fine, after suggesting jokingly that the city should feast him at public expense for the great service he had rendered it (as an eternal questioner of its practices). The jury was not amused. He was condemned to death and forced to drink the hemlock. AFTERMATH OF PELOPONNESIAN WAR With its defeat of Athens, Sparta was clearly the winner of the Peloponnesian War. This victory placed it in a complex position, which in turn led it to intervene in Greek affairs, with cumulatively weakening effects for itself. To begin with, there was the question of the Asiatic Greeks (the ones living in Asia Minor). What would be there relationship to Persia? According to a treaty brokered back in 411, the Spartans were to allow the Persians to assume control of the Asiatic Greeks – this was in exchange for financial backing from Persia that would enable them to build and equip a fleet. Over the next 15 years, Sparta reneged on this plan. Generals were spent overseas to guarantee some sort of independence for the Asiatic Greeks. The Persians were pushed back, but this initiative was costly to Sparta. The Persians turned on the Spartans, as a way of paying them back for their treacherous behaviour, and started funding various mainland city states. These city-states (Athens, Corinth, Thebes and Argos) entered into a state of war with Sparta. This war, called the Corinthian War, started in 395 over a border dispute in central Greece. The dispute drew the above city-states in because they were resentful of Sparta‟s meddling in their local affairs. And with money given to them by the Persians, they were able to muster a fleet and combat Spartan influence in Asia Minor and on the mainland. Athens, in particular, proved very successful. Under Conon, a leader who had been active during the PW, they managed to regain elements of their empire in the Aegean. This development frightened the Persians and eventually they stopped funding the anti-Spartan coalition. In 387 peace was finally brokered between Sparta and Persia – this peace is called The Peace of Antalcidas (Antalcidas was the Spartan naval commander). It stipulated that the Asiatic Greeks would belong to Persian and that all other Greeks would be autonomous (with the exception of three island states that the Athenians had come to possess). Worried that Persia would throw its financial weight behind Sparta, Thebes, Argos, Corinth and Athens agreed to these terms. The consequences of the Corinthian War were telling. Persia regained possession of Ionia. Sparta was still in a position of dominance on the mainland because the idea of autonomous states would allow it to break apart coalitions (Thebes and its allies, Athens and its allies, Corinth and its allies etc) that had formed against its rule and influence; at the same time such dominance was artificial because its own military strength was being overdrawn. Battle of Leuctra (371) In the aftermath of the Corinthian War, there was more infighting among the poleis. Sparta fought against Athens but the two would team up to battle the Thebans… the forming and breaking of alliances were endless. The Thebans, however, managed to do well for themselves. With the appearance of Epaminondas and his political ally Pelopidas, the city of Thebes was able to throw the Spartans from their territory. They then subjugated the cities around them to form a Boeotian League. The Spartans did not want Boeotia united in a common front against Spartan influence. A Spartan army (consisting of 700 full Spartan soldiers as well as allies) marched into Boeotia to a place called Leuctra. There they were confronted by a numerically inferior Theban army. The two sides clashed and, through the use of innovative tactics, the Thebans prevailed! A Spartan army had been forced to abandon the battlefield! Capitalizing on this victory, Epaminondas encouraged various city state sin the Peloponnese to rebel against Sparta. Banding together under Epaminondas‟ leadership, these city-states liberated Messenia and the helots. This act weakened Sparta further. Battle of Mantinea (362) Having defeated the Spartans at Leuctra, the Thebans worked hard to win control of a large part of the Peloponnese. This stirred resentment among Sparta‟s remaining allies as well as Athenian fears. The two contingents joined battle in 362 at Mantinea (north of Sparta in the Peloponnese). King Agesilaus II of Sparta led the pro-Spartan forces (including an Athenian component) and Epaminondas led the Theban side. The Thebans again wound up defeating the Spartans, although the defeat wasn‟t overwhelming and Epaminondas himself was killed in this exchange. Before dying, he urged the Thebans to make peace with Sparta. Unfortunately for all parties concerned (including Persia who had been meddling in Greek affairs all this while) it was too late. Another player on the scene understood all too well that the major mainland city-states were exhausted. He understood, too, that it was time to move in for the kill. I‟m talking about Philip II, king of Macedon MACEDONIA Macedonia is a region to the north of mainland Greece. It is bounded by Thrace on the east and Illyria on the west, both very rough regions. Macedonia itself consisted of the valley with a capital (in which the king resided) and the upperland with its mountainous neighbourhoods and unruly tribes. Although the Macedonians spoke a dialect of Greece, and had some of the same cultural and religious practices of the Greeks, they were not considered Greek by their neighbours to the south nor did they think of themselves as Greek. Macedonia had very few cities (the hallmark of life among the Greeks) were ruled by a king and were comparatively rough. Drinking, hunting and war were favourite pastimes – as an initiation rite, adolescents had to spear a boar and kill an enemy soldier before being accepted among the ranks of men. While Macedonia had on occasion meddled in the affairs of various Greek city-states, generally speaking their own situation had been too precarious for them to consider any telling movement south. Any king had to deal with aristocratic rivals, there were the independent tribes to control, and both the Thracians and Illyrians were always causing them trouble. At the same time, the mainland Greeks had always been strong and capable of pushing their northen neighbours back. All of this changed with the exhaustion of the Greeks in the aftermath of the PW, and the rise of Philip of Macedon. Philip Philip was the youngest of three sons of Amyntas, king of Macedonia. He spent some time in Thebes (where he observed the tactics of Epaminondas). After the death of his two older brothers, he assumed the Macedonian throne. He reorganized the Macedonian army, deploying the phalanx in a new innovative fashion and arming it with the sarissa, a long spear/pike. He also demonstrated greater mastery of the art of besieging cities. Over the next few years, he fought successful campaign against the Illyrians and Thracians. He also won over territory in the north that the Athenians had captured (in their effort to resuscitate their old empire). He sent his army into Thessaly and central Greece and scored numerous victories against the region‟s poleis. Bit by bit he encroached on Theban and Athenian holdings. The Athenian orator Demosthenes spent most of his professional career warning his fellow Athenians against the expansionist policies of Philip (these speeches are known as Philippics). Through his efforts Athens eventually allied itself with Thebes. In 338, Philip marched south against Athens. At Chaeronea (in Boeotia) an allied force of Athenians and Thebans met Philip in battle and were comprehensively defeated. Most major Greek poleis (except Sparta which was a shadow of its former self) accepted Philip‟s rule. Indeed, they joined the League of Corinth, an alliance designed 1) to stop the perpetual infighting that had dogged mainland states in the aftermath of the PW and 2) to facilitate the creation of a punitive expedition against Persia. Philip was already embarking (in a minor way) on a retaliatory campaign against Persia. In 336 he sent an expeditionary force to Asia Minor. It met with a great deal of success in that numerous Asiatic Greek states rebelled against Persia (and the terms of the Treaty of Antalcidas) and swore loyalty to Philip‟s cause. An outright campaign was planned. Unfortunately, Philip was assassinated in 336 by a Macedonian named Pausanias (who was rumoured to be an old lover of the king). Chaos set in. This is when Alexander the Great enters onto the stage. ALEXANDER Alexander was 20 at the time of Philip‟s assassination. These were difficult times for him. He was the obvious heir to Philip‟s throne but did have rivals (Philip had several wives). There were Macedonian aristocrats, moreover, who weren‟t necessarily interested in backing his claim. At the same time the Illyrians and Thracians subdued by Philip were beginning to think this would be a good time to declare their independence and escape Macedonian rule. Finally, the Greek city-states to the south were contemplating rebellion. Alexander marched south first. By marching through Thessaly (northern Greece) and camping before Thebes, he was able to get the Greek city-states to abide by the terms of the League of Corinth. He then headed north and campaigned fiercely against the Thracians and Illyrians. He brought them to the point of defeat when rumours of his death led to further talk of rebellion down south. This time Alexander marched south (335) and took Thebes captive. Deciding to end the rebellion by a show of force, he destroyed the city and sold the population into slavery. This was a brutal act but one that caused the other city-states to fall in line. By this time, too, he had liquidated all potential heirs to the throne. With the affairs settled in Greece, Illyria, Thrace and Macedonia itself, he could turn his attention to his father‟s unfinished business in Persia. War with Persia Alexander thought of his invasion of Persia as a continuation of the Greek war against Asia starting back as early as the Trojan War. He also thought of this as a lifelong campaign. Putting Antipater (one of his father‟s most trusted generals) in charge of Macedonia, he made his will and marched into Asia (334) with some 30,000 troops. His first major battle with the Persians was at Granicus. Here he scored a decisive victory which gave him control over the Asiatic Greeks. A second major battle took place the following year (333) when Alexander fought a Persian army led personally by the king, Darius III. Alexander scored a telling victory here. This embarrassed Darius, who retreated in to the interior of his empire to amass new forces. He also tried to reach an agreement with Alexander, but to no avail. For his part Alexander traveled about the Mediterranean, going to Syria (and capturing the city of Tyre with his siege engines) and marching into Egypt. In Egypt, Alexander founded Alexandria. The third major battle with the Persians was at Gaugamela (in modern Iraq) in 331. Again Darius was overwhelmingly defeated. While Alexander helped himself to huge quantities of gold, Darius wanted to head east with some loyal soldiers. He was murdered first by one of his lieutenants. In principal, the empire now fell to Alexander. He continued to travel through the empire (mainly further east), subduing populations that didn‟t accept his rule. As time went on, he relied more on Persian soldiers and began to adopt Persian ways and fashions – much to the disgust of his Macedonian troops. In a fit of drunkenness he murdered one of his loyal captains, Clitus. He married Roxana (327), a foreign princess, and tried to get his troops to prostrate themselves before him (a Persian custom) but to give it up when they protested. He crossed the river Hydaspes (326)where he fought an expensive battle against the local king (Porus) and won. He wanted to march further into India, but his men refused. They had had enough war and conquest. Alexander started marching west. After further battles (and attempts to pacify certain regions in Persian empire), he arrived in Babylon in 323. Here he died of fever contracted from his generally weak condition and chronic drinking. His empire consisted of Greece, Macedonia, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, parts of Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan. His last words to his generals, in answer to the question who his heir was to be, were “to the strongest”. Certainly there was a struggle after he was gone – something that is called the Wars of the Diadochi (successors). The empire wound up passing into the hands of Perdiccas (Alexander‟s cavalry leader). He murdered several rivals and appointed numerous satraps – leaders who would have ruled different regions but who were subordinate to him. Perdiccas was eventually murdered and, in fact, no individual leader was able to hold the empire together. Two generals/satraps of interest, who wound up establishing long lasting dynasties for themselves, were Ptolemy and Seleucus. These generals quickly moved into various areas of his empire and established enclaves for themselves. Ptolemy (and his heirs) wound up controlling Egypt (until the last Ptolemaic heir, Cleopatra, lost this territory to Rome, in 31 BC). Seleucus established a dynasty that controlled a large swathe of territory to the east – the satrapy („province‟) of Babylon, Persia proper and Media. His successor, Antiochus, would fight the Maccabees in Judaea over the cultural/religious direction that this territory would move in. (This struggle is commemorated in the holiday of Hanukkah). Alexander‟s Legacy Alexander‟s conquests are significant because Greek culture takes root over a much larger area than was previously the case. Until Alexander, populations were following Greek ways and ideas in Greece itself, Ionia, the Aegean isles, Southern Italy and Sicily. Now the Greek perspective was cast further abroad, across the whole of modern Turkey, into the heart of Persia, in Egypt and as far afield (briefly) as Afghanistan. This spread of Greek culture is known as Hellenism. Archeologists have uncovered a number of cities that were designed according to the Greek model and contained Greek public buildings built in accordance with Greek architectural schemes. In Egypt (for example), Alexandria became the country‟s capital and the power base of the Ptolemies. Here the Museion was established – a precinct dedicated to everything sacred to the nine Muses. It contained a philosophical school, a school where music and poetry were composed and studied, a school for anatomy as well as a famous library that, at its height, contained some 700,000 papyri (it was burned to the ground in Julius Caesar‟s day). Hellenism meant the death of the city-state. The typical citizen was no more. The polis had been supplanted and people now belonged to the cosmopolis – a system of government that tied them altogether, but was too large to allow their inclusion. This change gets reflected in the philosophy and literature of the day. TERMS Socrates, trial (399), Apology, atheism, hemlock, Crito, Critias, Alcibiades, Arginusae, Corinthian Wars, Argos/Athens/Corinth/Thebes, Sparta, Treaty of Antalcidas, Persia, Epaminondas, Pelopidas, Battle of Leuctra, Messenia, Battle of Mantinea, Macedonia, Philip II, Illyria, Thrace, Demosthenes, Philippics, Chaeronea (338), League of Corinth, Alexander, Persia (334-323), Granicus (334), Issus (333), Gaugamela (331), Darius III, „to the strongest‟, Perdiccas, Ptolemy, Seleucus, Hellenism, Alexandria, museion, library, cosmopolis,