* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech

Preposition and postposition wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Compound (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Comparison (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian declension wikipedia , lookup

Literary Welsh morphology wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Contraction (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian nouns wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Vietnamese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

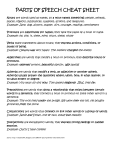

Confirming Pages 2 chapter outline Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 31 INTRODUCTION NOUNS PRONOUNS ADJECTIVES VERBS ADVERBS PREPOSITIONS CONJUNCTIONS INTERJECTIONS HOMOPHONES CHAPTER SUMMARY EXERCISES GLOSSARY TERMS 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 32 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech INTRODUCTION This chapter examines the parts of speech that compose the prose you will be using to write reports. This is often the scariest part of writing: writing with proper grammar and syntax. Sometimes when students hear terms such as noun, pronoun, verb, adjective, preposition, conjunction, interjection, adverb, and homophone, confusion sets in. But in truth, most of you probably already know more than you realize, and you are really skilled at using the parts of speech. However, reviewing the terms and seeing how they work in reports will make your writing more effective. For example, let’s consider the noun. In elementary school some teacher certainly introduced you to the noun. It is likely he or she told you “nouns represent people, places, or things,” and indeed this is an accurate way of thinking about nouns. Nouns also include actions, qualities, and beliefs. All of this will be better explained as this chapter unfolds. Let’s now consider the noun’s assistant—the pronoun. Correctly using nouns and pronouns in an incident is essential. The question may be, however, what point of view were you using when you wrote these nouns and pronouns? The point of view of a piece of writing is the perspective from which that writing is written: first person (I or we), second person (you), or third person (he/she/it/one or they or some other neutral noun or pronoun). Table 2-1 shows both common personal pronouns and their possessive forms. When one of the authors of this book first began policing back in the 1980s, most police reports were written in what can be described as third person, or thirdperson omnipotent. Technically, third person involves the writer of a narrative avoiding the use of the pronoun I or we. Rather, the writer used terms like the author, the writer, or in the case of these early police reports, the responding officer frequently written as R/O. Under these circumstances officers would write sentences such as this: R/O arrived at the scene and observed two male suspects running North, down Oak, away from the victim who was lying on the ground in front of the ATM located at the corner of Maple and Oak. table 2-1 Common Personal Pronouns and Their Possessive Forms Point of View Singular Plural Police Use First person I, me (my, mine) we, us (our, ours) Singular (Plural) Second person you (your, yours) you (your, yours) I, me (my, mine) Third person he, him (his) she, her (her, hers) it (its) them, they (their, theirs) you (your, yours) Officer (Officers) Suspect (Suspects) Victim (Victims) Witnesses (Witnesses) ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 32 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 33 Similarly, others in the narrative report were described in the third-person pronouns such as the suspect, the witness, the victim, and so forth. In some cases, departments preferred the use of the officer’s name: Officer Johnson arrived at the scene and observed two male suspects running North, down Oak, away from the victim. . . . But this always seemed a little stilted since Officer Johnson was the author of the report, and would be signing it at the bottom. Today, most police departments prefer the use of first-person singular when writing in the voice of the police officer. Thus, if Officer Johnson was writing today, she would write: I arrived at the scene and observed two male suspects running North, down Oak, away from the victim. . . . Similarly, suspects, witnesses, and victims have begun to be listed by their pronouns and proper nouns (their specific names) when that information is known. While suspects may not be known in all cases, frequently this information will be obtained when interviewing the victim and/or a witness. Thus, when the writing the narrative, an officer might write something such as: Victim Ronald Miller identified the suspects as Earl Martin and Franklyn Burton. Suspects Martin and Burton were described as. . . . The definitions for the various points of view a writer may use are discussed in the following sections. First Person When writing the narrative portion of a police or correctional report, you should use first-person narration. You are the I who describes what you observed, did, or said, and what was told to you by others. When referring to other people in the narrative, use their proper names (nouns). You should also note that incident reports must be consistently written in past tense, not present tense. Second Person The second-person point of view, which emphasizes the reader, works well for giving advice or explaining how to do something. Second-person point of view works well in certain literary devices and types of writing but is seldom used in police or correctional reports. It may be used in offering directions or in rule books, textbooks, and some other forms of correctional writing. Third Person At one time writing in third person was the standard practice in police and correctional reports. When using third-person narration, you use either proper names (nouns) or pronouns such as he, she, and they when referring to people in the narrative. Biographical narratives (writings about other people’s lives) and expository writings generally are written in the third person. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 33 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 34 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech NOUNS One of the questions many officers frequently have is whether or not to capitalize the first letter of a noun. The technical distinction here is usually referred to as proper nouns, which refer to particular people, places, things, or ideas, versus common nouns, which refer to everyday names of people, places, things, or ideas (Fawcett, 2004). Proper nouns are capitalized, as in the cases of Mr. Johnson, Dr. Deeds, England, October, and Chief Markson. Common nouns may be illustrated by the terms month, officer, art, anger, and age. Officers may commonly encounter other types of nouns, including concrete nouns, abstract nouns, and compound nouns. Concrete nouns refer to things that can be seen felt, smelled, or heard. Examples of concrete nouns are water, dirt, gas, pepper, books, guns, knives, and cuffs. Abstract nouns describe qualities, concepts, and beliefs; for instance, courage, hunger, liberty, detention, and custody. Compound nouns comprise more than a single word, yet represent only a single noun; for instance, Orange County, traffic stop sign, half moon, and detention cell. In some cases, compound nouns are a combination of two or more small words to form a single word, such as tooth and paste to form toothpaste. In addition to standard rules of grammar related to nouns, many police departments require that officers use all capital letters when writing names of individuals used in the narrative of incident reports (these names are proper nouns). Some departments use this device to make it easier to locate names when reviewing reports. So, what is the actual purpose of a noun? Basically, nouns serve as the subject of a sentence, or as some sort of complement (direct or indirect object of a verb or a preposition). These other structural terms related to the sentence will be more fully explained later in this book. For now, let’s consider pronouns. PRONOUNS Pronouns are words that can be used to replace a noun or another pronoun (Fawcett, 2004). Okay, again many of you may recall that fourth-grade (compound noun) teacher who told you that “pronouns take the place of a noun.” That probably makes a little more sense now that you understand what a noun actually is. But what exactly does it mean when a word takes the place of a noun? Let’s consider the following paragraph written with only nouns: I entered the premises at 1427 Hillsdale Street and found Officers Murphy and Constence speaking with the victim Ms. Hillary Ferguson. Ms. Ferguson stated that her daughter Jessica Ferguson and Jessica Ferguson’s friend from school Madelaine Katz were on their way to the home of Ms. Hillary Ferguson when confronted by the suspect Martin Podster. Officer Murphy questioned Jessica Ferguson and asked if Ms. Hillary Ferguson knew Jessica Ferguson would be walking home with Madelaine Katz. Many readers will read this passage and know there is some problem with the way it has been written. What might this problem be? It is using only proper nouns rather than proper nouns and pronouns. Let’s consider how this paragraph might be rewritten: ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 34 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 35 I entered the premises at 1427 Hillsdale Street and found Officers Murphy and Constence speaking with the victim Ms. Hillary Ferguson. Ms. Ferguson stated that her daughter Jessica Ferguson and her daughter’s friend from school Madelaine Katz were on their way to Jessica’s home when confronted by the suspect Martin Podster. Officer Murphy questioned Jessica Ferguson and asked if her mother knew she would be walking home with Madelaine Katz. As you reread the passage with the pronouns added it is likely that uneasy feeling you had when reading the first version is gone. As in the case of the nouns, there are several different types of pronouns, including personal pronouns, possessive pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, relative pronouns, reflexive pronouns, interrogative pronouns, and indefinite pronouns. Let’s consider these various pronouns. Personal Pronouns Personal pronouns represent people or things: I, me, you, he, him, she, her, it, we, us, they, them. Officer Thomson [proper noun] came to see him [personal pronoun] about a stolen car. Possessive Pronouns Possessive pronouns indicate possession or ownership: mine, yours, hers, his, theirs, ours, its. Sergeant Davidson [proper noun] uses his [possessive pronoun] pen to write the report about the fight. Demonstrative Pronouns Demonstrative pronouns demonstrate or indicate a particular person or thing: this, that, these, those. That [demonstrative pronoun] gun is his [possessive pronoun] service weapon. Relative Pronouns Relative pronouns are words that relate one part of the sentence to another, or refer to some other element of the sentence: who, whom, which, that, whose. The witness whose [relative pronoun] home the officers entered was sitting on the couch. [Notice how the word whose refers to the word witness.] The knife [common noun] was dripping with blood, but officers could not determine whose [relative pronoun] weapon it was. Reflexive Pronouns Reflexive pronouns, also referred to as intensive pronouns, reflect or refer to someone or something else in the sentence in a kind of possessive manner: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 35 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 36 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech An officer [common noun] must ask himself [reflexive pronoun] whether or not shooting a suspect [common noun] is the proper course of action. The correctional officer [compound noun] thought to himself [reflexive pronoun] how evasive the inmate [common noun] had been when questioned about the theft. Interrogative Pronouns Interrogative pronouns ask a question or interrogate in the course of the sentence: who, whom, which, whose, what. Officer Billiet [proper noun] could not determine what [interrogative pronoun] the suspect [common noun] was trying to tell him [personal pronoun]. Indefinite Pronouns Indefinite pronouns include all, another, any, anybody, anyone, both, each, either, everybody, everyone, everything, few, many, most, much, neither, no one, nobody, none, nothing, one, other, others, several, some somebody, someone, and something. Indefinite pronouns are sometimes confused with adjectives because the writer mistakenly thinks these words are modifying a noun or pronoun—which is, in fact, the job of the adjective. Let’s consider adjectives. ADJECTIVES As suggested earlier, adjectives are words that modify or describe a noun or pronoun (Fawcett, 2004). The witness [noun] identified the tall [adjective] suspect [common noun]. Certain words such as a, an, and the are a special category of adjective called articles. The words a and an are referred to as indefinite articles because they do not indicate anyone or anything in particular—no specific noun or pronoun: a gun, an amulet. The word the is called a definite article because it names someone or something specific: the gun, the amulet. Officer Billet [proper noun] found a [indefinite article] fingerprint [common noun] on the [definite article] beer bottle [common noun]. Officer Billet [proper noun] found a fingerprint on a [indefinite article] beer bottle. He noticed that the [definite article] fingerprint on the [definite article] bottle was bloody. Officer Billet [proper noun] found the [definite article] gun [proper noun]. Adjectives describe or indicate amounts, or limit size or quantity of a noun or pronoun. In some cases, adjectives show relative comparisons between elements in a sentence; for instance: big, bigger, biggest; good, better, best; fast, faster, fastest; tall, taller, tallest; slow, slower, slowest. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 36 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 37 The officers [common noun] captured two suspects [common noun] because their [possessive pronoun] cruiser [common noun] was faster [adjective] than the suspect’s car [compound noun]. VERBS Verbs are the most essential words in a sentence. Some verbs indicate elements of action and may actually be called action verbs. These are the most common verbs used in writing and speaking; they are usually pretty easy to identify in a sentence. There are four basic parts of verb forms: present, past, past participle, and present participle (Fawcett, 2004). The present form of a verb is considered the common form; for instance: run, jump, punch, kick, and hammer. The past and past participle actually look the same, as in the case of ran, jumped, punched, kicked, and hammered. The present participle usually is formed by addinging to the present tense (sometimes called the present infinitive), as in running, jumping, punching, kicking, and hammering. The [article] suspect [noun] ran [verb] down the alley. The [article] suspect [noun] was kicking [adjective] the arresting officer [compound noun]. In addition to action verbs, there are verbs of being. Verbs of being include words such as was, is, am, were, or similar forms of being. Officers [common noun] were [helping verb] looking [verb] for a [article] suspect [common noun]. The [article] district attorney [common noun] asked [past-tense verb] the [article] officer [common noun] where she [pronoun] was [verb of being] when she [pronoun] made the [article] arrest [noun]. There are two main types of verbs: action verbs and linking verbs. Action verbs are words such as ran, played, or kicked. Some verbs serve the function of linking in a sentence. These words include appear, feel, look, remain, smell, stay, become, grow, prove, seem, sound, taste. The biggest confusion is that these verbs sometimes act as action verbs, while at other times they serve as linking or helping verbs. The basic test is whether you can substitute a form of being (am, is, was, and so on) and allow the sentence to make sense. If it does, the verb is a linking verb. The coffee tasted too bitter for the officer to digest. TEST: The coffee is (was) too bitter for the officer to digest. [This sentence works and taste is a linking verb.] What about the following: The officer tasted the bitter coffee. TEST: The officer is (was) the bitter coffee. [Hey, that doesn’t work because taste is not a linking verb in this sentence.] ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 37 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 38 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech ADVERBS Certain words modify or change a verb or an adjective; these are known as adverbs (Fawcett, 2004). In fact, adverbs may also modify other adverbs. Adverbs typically describe the following sorts of things: • • • • • Where something is: there, here, outside, inside, nearby, far away, under, above. When something occurs: now, then, later, immediately, yesterday, tomorrow, the next day. How something occurs: quickly, slowly, stupidly, happily, effortlessly. How often something occurs, or its duration: often, seldom, frequently, once, twice, never, always. How much of something (the extent of something): hardly, extremely, minimally, greatly, more, less, too, excessively. Yesterday, [adverb] Officer Jones [proper noun] apprehended [action verb] two suspects [common noun]. In the preceding example, yesterday modifies the verb apprehended. In effect, the word yesterday describes when the action of apprehending the suspects occurred. Many adverbs also may be formed by simply adding an –ly to the adjective; so when you see a word ending in an –ly, usually it is an adverb. Table 2-2 shows a series of common adjectives and their adverb forms. Some adverbs do not work with the –ly convention. For example, the word fast cannot be changed to an adverb by adding –ly; there simply is no word fastly. So, an example of this might be as follows: The police cruiser moved fast, but was no match for how fast the suspect’s car was moving. [Notice that the suspect’s car does not move fastly; there is no such word as fastly.] table 2-2 Adjectives to Adverbs ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 38 Adjectives Adverbs bad badly quick quickly awful awfully kind kindly quite quietly happy happily shy shyly pensive pensively cold coldly neat neatly keen keenly coarse coarsely 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 39 The correctional officer chased the inmate down the gallery; the chase lasted a long time, but not as long as the chase last week. [Again, there is no such word as longly, so the adverb remains long.] Many students, police, and correctional officers love a special form of adverb known as a conjunctive adverb. Conjunctive adverbs join independent clauses together to form a single sentence; they are sometimes referred to as transitional words and phrases. These words should not be overused. Table 2-3 lists some common conjunctive adverbs. Because conjunctive adverbs are not true conjunctions, a semicolon and a comma are required when connecting two independent clauses or conjunctive adverbs. Conjunctive adverbs, other than so or otherwise, require a semicolon preceding them and a comma following them. Conjunctive adverbs are used to join short sentences (complete clauses) together to form more complex thoughts; however, you must punctuate correctly: (Hey, did you notice the use of the conjunctive adverb however in the last sentence?) 1 2 3 4 Each clause on either side of the conjunctive adverb must be a complete thought. A semicolon (;) must be placed in front of the conjunctive adverb and a comma (,) immediately following it. The two clauses are closely related thoughts or ideas. You have used the correct conjunctive adverb. As indicated, a conjunctive adverb connects two ideas (independent clauses). If the words listed in Table 2-3 interrupt a thought, they are not conjunctive adverbs and are not punctuated as such. Similarly, you cannot simply connect two independent thoughts to form a single compound sentence. For example: The correctional officer examined the inmate’s clothes; accordingly, he left for lunch. After reading the previous example, hopefully you are scratching your head and thinking, “Huh? I don’t follow what the first clause has to do with the second one.” Because the two clauses in the example are unrelated, the use of a conjunctive adverb (accordingly) is incorrect. Here is a good example: The correctional officer examined the inmate’s clothes; consequently, he discovered the illegal contraband. table 2-3 Common Conjunctive Adverbs accordingly for example in particular now afterward furthermore instead otherwise again generally likewise similarly also hence meanwhile so besides however moreover still beyond in addition nevertheless then consequently incidentally next therefore finally indeed nonetheless thus ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 39 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 40 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech Comparisons with Adjectives and Adverbs Sometimes you may want to make a comparison between things, or indicate how one thing might measure up to another. You may want to indicate that one suspect is taller than another, or heavier than your partner, or older than the witness. In writing this in a report, you would use one of three possible degrees of adjectives and adverbs: a positive degree, a comparative degree, and a superlative degree. • A positive degree makes a simple statement about a person, place, or thing. The correctional officer is very tall. [positive degree adjective] • A comparative degree compares two, and only two, people, places, or things. The correctional officer was taller [comparative adjective] than his sergeant by five inches. • A superlative degree compares more than two people, places, or things. The correctional officer is the tallest [superlative degree adjective] man in the facility. Table 2-4 shows a table of different degrees of adverbs and adjectives. A quick look at Table 2-4 reveals that you can change an adjective or adverb from its positive degree to its comparative degree by adding an –er or –ier. Similarly, you can move the adjective or adverb from comparative degree to superlative by adding an –est or –iest to the positive degree form. Occasionally, you will have an adjective or adverb that requires the addition of the word more or most to move the degrees from positive to comparative and then to superlative. Consider these examples: The captain of the guards is a capable [positive degree adjective] man. The warden is more capable [comparative degree adjective] than the captain of the guards. The superintendent is the most capable [superlative degree adjective] of all the personnel. The test here is largely one by ear and is similar to adding –ly to a verb to make it an adverb. In other words, if you were to restate one of the previous examples table 2-4 Adjective and Adverb Degrees ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 40 Positive Comparative Superlative dirty dirtier dirtiest old older oldest deep deeper deepest big bigger biggest smart smarter smartest 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 41 and substitute the positive degree changed with an –er or –ier, it would not sound correct. The warden is more capabler than the captain of the guards. To be sure, capabler is not a word, and it simply sounds incorrect in the sentence. Some adjectives will not follow these basic rules of degree and are considered irregular; the word itself actually changes as you move from the positive degree to the comparative and/or the superlative. Consider these irregular examples: The probationary officer writes reports well, but his training officer writes better; their sergeant, however, writes best. The correctional officer searches cells badly. His trainee actually does a worse job at searching, and the recruit demonstrates the worst skill at searches. Corporal Johnson is a good marksperson. Sergeant Morley is a better shot, but Lieutenant Brown is the best marksperson. I have too much paperwork to finish in one day. You have even more paperwork to finish. Officer Jackson has the most paperwork to finish. Looking back at the last few pages, it is clear that there are a lot of rules associated with comparisons. Certainly this can make things a bit confusing. One rule of thumb is to try to keep adjectives and adverbs of comparison as simple as possible, and to read them aloud to hear how the sentence sounds. For example, read each of the following sentences aloud and see if you can hear the difference between the correct and clear form, and the awkward and incorrect form. The box on the table was less big than the one on the floor. [awkward] The box on the table was smaller than the one on the floor. [clear] The officer lifting weights was more strong than the other officer. [awkward] The officer lifting weights was stronger than the other officer. [clear] The officer felt less powerless when he drew his gun. [awkward] The officer felt more powerful when he drew his gun. [clear] It is also important to be careful about where you place an adverb. Incorrect placement can make the sentence mean something completely different from what you intended. Consider these examples of proper and improperly placed adverbs. I had only been eating for ten minutes when the call came in to respond to a robbery in progress. [weak and improper placement] This sentence actually says this: I had only been eating [I hadn’t been sitting in a car, or running or dancing—only eating] for ten minutes when the call came in to respond to a robbery in progress. I had been eating for only ten minutes when the call came in to respond to a robbery in progress. [stronger and proper placement] ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 41 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 42 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech PREPOSITIONS Prepositions connect nouns or pronouns, which are called the objects of the preposition. The preposition and its object form a prepositional phrase. Grammar books usually define prepositions as words that connect or link nouns and pronouns to some other word in the sentence (Fawcett, 2004). The officer threw the gun in the air. The officer dropped the gun on the ground. The officer threw the gun under the car. The officer shot the gun at the firing range. The officer dropped the gun near the suspect. The underlined words link the two nouns, creating some sort of relationship between the words. These linking words are called prepositions. Table 2-5 provides a list of common prepositions. So, how do you remember what a preposition is? One suggestion is to think about the word position which conveniently appears in the word preposition. A preposition frequently indicates the position of something: in, outside, under, over, in front of, and so forth. It is also important to remember something else that your fourth-grade teacher probably told you: You should never end a sentence with a preposition. Unlike with certain forms of adverbs and adjectives, where written sentences when read aloud frequently do not sound right to our ears, prepositions at the end of a sentence sometimes do. This is because in colloquial spoken English table 2-5 Common Prepositions about below except near throughout above beneath excluding next to till according to beside following of to across besides for off toward after between from on under against beyond in on account of underneath along but in addition to onto until among by include out up around by way of including out of upon as concerning in front of outside with at considering in place of over within because of down in regard to past without before during inside since instead of through behind into like ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 42 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 43 (regular conversational English), people regularly end sentences with a preposition. Consider for the following sentences: With whom was the correctional officer speaking? [correct] Who was the correctional officer speaking with? [incorrect] If we read or speak these two sentences, many people will not notice that the second version is in error. In fact, many people reading that second example may find it hard to accept that this is not correct, because it is exactly how they speak (and likely write as well). These days, grammarians are saying that ending a sentence with a preposition is not always bad. Sir Winston Churchill was quoted as saying, “ending a sentence with a preposition is something with which I will not put up.” Churchill was mocking fussy grammarians who say you should never end a sentence with a preposition. Let your conscience be your guide and strive for well-written and easily understood sentences. CONJUNCTIONS In addition to prepositions, another word that links or conjoins words in a sentence is a conjunction. Thus the role of a conjunction is to connect words with other words, clauses, and ideas. There are three major categories of conjunctions: coordinating, correlative, and subordinating. Coordinating Conjunctions Coordinating conjunctions include words such as for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so. These words can be used to connect two independent clauses (Glenn & Gray, 2007). An independent clause is a complete thought. Typically, the conjunction is placed between the two clauses, preceded by a comma. Many grammar books recommend remembering coordinating conjunctions by thinking about the acronym FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so). The inmate was angry, but he did not hit the other man. The officer was hungry, so he decided to eat his lunch. Correlative Conjunctions Correlative conjunctions cannot work alone, but instead operate in pairs. These pairs appear in two places in a sentence and include both/and, either/or, neither/nor, not only/also, not only/but also, and whether/or. Did anyone see whether the suspect or his accomplice had a weapon? Neither the officer nor his partner could keep up the foot pursuit for more than four blocks. Subordinating Conjunctions Subordinating conjunctions are used to join a subordinating clause with a main clause. A subordinating clause depends on the rest of the sentence for its meaning. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 43 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 44 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech table 2-6 Common Subordinating Conjunctions after even though so long as although how so that as if than as if inasmuch as that as in in order that through as long as in that till as much as least unless as soon as now that until assuming that once when because provided that whenever before since whether even if while It does not express a complete thought, so it does not stand alone. It must always be attached to a main clause that completes the meaning. Table 2-6 provides a list of some of the most common subordinating conjunctions. You may have noticed that the word as is written in italics. That is to remember to mention a problem many people have when deciding whether to use the words as or like. (Hey, did you catch the use of the correlative conjunctions in that last sentence?) Traditionally, the word like is a preposition, and it should be followed by an object to create what is called a prepositional phrase. As is a conjunction, and it should be followed by a clause containing a subject and a verb. The inmate runs like a deer does. [incorrect—it is not necessary to repeat the verb does] The inmate runs like a deer. [correct] The inmate runs as a deer does. [correct—as is followed by a clause] In standard English, the word like is never used with clauses. INTERJECTIONS You may have noticed that periodically we pose questions about whether you caught some example of one of the grammatical rules described in this chapter. We frequently begin such questions with the term hey. Beginning a sentence with hey, gads, oops, well, whoa, wow, yikes, ouch, and similar words indicating some sort of emotion are called interjections. Interjections can either stand alone, or be included as part of a sentence. When an interjection is used as part of a sentence, it does not have any grammatical relation to the other words in that sentence. In other words, you can remove the interjection and the meaning of the sentence will remain unchanged (Glenn & Gray, 2007). Assuming the sentence had been grammatically correct with the interjection, it will remain grammatically correct if you remove it. In common writing, ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 44 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 45 when an interjection is used to express strong emotions or surprise and it stands alone, you should use an exclamation point (!) after the interjection: Wow! Is that really what you think? If you are employing milder terms in the middle of a sentence, you should use a comma after the interjections: Darn! that shoelace keeps coming undone. Interjections are not typically used in police or correctional reports, unless the officer is quoting a suspect, witness, or victim. In these reports, for example, an officer may write the exclamation of some profanity uttered by an inmate, suspect, victim, or witness verbatim, and in this case it may well be an interjection. HOMOPHONES Homophones are words that sound alike but have different meanings and spellings (Glenn & Gray, 2007). Words such as to, too, and two have very different spellings and meanings and are commonly misused. Some of these words will sound alike, such as sole/soul, break/brake, dear/deer, and ensure/insure. Others may sound similar but have different meanings, such as believe/belief, marry/merry, desert/ dessert, accept/except, council/counsel. Improper use of words may confuse the reader or can convey the wrong meaning of a sentence. It may also lead the reader to believe that the writer is incompetent or that the report was hastily written. Effective writers choose their words carefully and ensure that they are using the appropriate words and spelling. If you are uncertain about the correct meaning of a word, consult a dictionary before you use it in a sentence. Most word processing software programs with spell checkers will not always detect the improper use of these words. Remember that the quality of your written work reflects directly on you and that even small mistakes in grammar can tarnish an otherwise well-written report. The appendix provides a listing of the most frequently confused homophones. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 45 chapter summary 1. Nouns are the people, places, things, and ideas that make up a written narrative. Knowing when and how to properly integrate nouns in a sentence makes for a richer and more accurate written report. 2. Pronouns take the place of a noun in a sentence. They allow the writer to use words such as I, me, her, him, or them in place of a noun. In this way the narrative is easier to read and not so redundant. Several different types of pronouns are used to take the place of a noun. 3. Adjectives are words that modify or describe a noun or pronoun. They allow a writer to describe, indicate amounts, or limit the size or quantity of a noun or pronoun. 4. Verbs are the most essential words in a sentence. They indicate the elements of action or help link a sentence together. 5. Adverbs are words that describe a verb or an adjective. Adverbs typically describe how, when, where, how much, or how many in a sentence. 6. A preposition is a word that connects or links a noun and a pronoun to some other word in a sentence. They establish a relationship between these words. 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages 46 chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 7. Conjunctions are words used to link or conjoin words in a sentence. Their role is to connect words with other words, clauses, and ideas. 8. Interjections are words that can either stand alone, or be included as part of a sentence. When an interjection is used as part of a sentence, it does not have any grammatical relation to the other words in that sentence. They are most often used to show or indicate emotion. 9. Homophones are words that sound alike but have different meanings and spellings. If you are uncertain about the correct meaning of a word, consult a dictionary before you use it in a sentence. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 46 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech 47 Exercises—Using the Parts of Speech INSTRUCTIONS: In each sentence, cross out the noun used incorrectly and write the correct noun in the space provided. 1. The police chief had very strong opinions about the roles of men and woman in police work. 2. Younger officers often mimic the conduct of their peer in dealing with combative suspects. exercise 1 USING NOUNS CORRECTLY 3. The suspect gained entry in the residence and took a set of rare coin. 4. The narcotics agent detailed the activity of multiple suspect at the residence under suspicion for manufacturing methamphetamine. 5. Research on child abuse indicates that either parent might be capable of abusing their child. 6. When parents do not use the proper child safety seats when driving they risk the life of their children. 7. Talking during a public meeting is disrespectful of other who may be trying to listen to the speakers. 8. The witness indicated that one of the girl was seen leaving the scene of the robbery. 9. The attorney stated that he was acting on behalf of his clients, Mr. Smith, when he made the motion during the trial. 10. Police officers are one of the few persons in the criminal justice system who can detain suspects. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 47 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech exercise 2 48 USING PRONOUNS CORRECTLY INSTRUCTIONS: In each sentence, circle the correct pronoun. 1. Officer Manning placed the suspect in the backseat of (his / their) patrol car. 2. The suspects ran from the scene and left contraband in the backseat of (his / their) car. 3. Mary told the officer that her driver’s license was located in (their / her) purse. 4. Each police agency has (its / their) own distinct style. exercise 3 5. The sheriff’s office honored (its / the) senior officers with plaques signifying years of service to the agency. WRITING CLEARLY INSTRUCTIONS: Rewrite each sentence correctly in the space provided. (Answers may vary.) 1. On the radio they advised that the road was closed. 2. Officer Melton told the suspect that he should not have lied about his identity. 3. In the city of Fairfield they arrest litterers. 4. On the news, it said that the suspects were seen driving a blue-colored sedan. 5. Sergeant Smith is an excellent typist, yet he has never had a lesson in it. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 48 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech INSTRUCTIONS: In each sentence, circle the correct adverb or adjective. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Have you ever seen (real / really) marijuana? Try to approach the suspects (quietly / quiet). The smell from the decomposing body was (awful / awfully). The officer (gladly / glad) gave the citizen directions to the courthouse. Officer Brown, a (high / highly) skilled marksperson, was able to shoot a perfect score at the firing range. The officer (carefully / care) approached the door to the suspect’s residence. Detective Green smelled an (unusual / unusually) odor coming from the garage. Recruit Barnes performed (poor / poorly) on his timed run for the police academy. The weapon used by the robbery suspect (actual / actually) turned out to be a pellet gun. The witness (hastily / hasty) wrote a statement as to what she had seen. INSTRUCTIONS: In each sentence, circle the correct preposition. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. The suspect was found hiding (in / on) the bedroom. After the crash the suspect’s vehicle came to rest (in / on) Chesterfield Street. The child was struck by a vehicle after he ran (in / on) the street. (In / On) July, the state issued new restrictions for underaged drivers. (On / In) Sunday, the victim discovered that his house had been burglarized. That mess (in / on) your locker must be cleaned up. The town of Myrtle Beach is located between Charleston and Wilmington, North Carolina, (on / in) the coast of South Carolina. 8. Mr. Johnson also owns several businesses (in / on) Santa Barbara. 9. Mrs. Mason placed several items (on / in) the table in front of the witness. 10. Officer Patton stepped (in / on) the bridge before jumping into the water below. ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 49 exercise 5 USING PREPOSITIONS CORRECTLY exercise 4 USING ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS CORRECTLY 49 04/11/11 11:57 AM Confirming Pages chapter 2 Good Writing Means Writing Well: Understanding the Parts of Speech glossary terms exercise 6 50 ber11463_ch02_031-050.indd 50 USING HOMOPHONES CORRECTLY INSTRUCTIONS: In each sentence, circle the correct homophone. 1. The driver stated that he engaged the emergency (break / brake) before his vehicle struck the tree. 2. The state trooper’s patrol car was struck as he pulled through the (break / brake) in the highway median. 3. During the investigation blood stains were discovered on the (sole / soul) of the suspect’s shoe. 4. During the interview the suspect invoked his right to speak with his legal (council / counsel). 5. The city ordinance banning alcohol on the beach was voted in by the city (council / counsel). 6. The victim states that she told the suspect that she could not (accept / except) a ride in his car. 7. The crime scene technician collected everything in the bedroom (accept / except) the carpet on the floor. 8. Sergeant Grant told Officer Smith to thoroughly search the suspect before he was transported to the booking facility to (ensure / insure) that he had no weapons or contraband on his person. 9. Detective Barnes stated that the suspect would be arrested to (assure / ensure) the victim that justice would be served and she would have her day in court. 10. The condemned prisoner ordered chocolate cake for (desert / dessert). Adjective 36 Adverb 38 Conjunction 43 Conjunctive adverb 39 Coordinating conjunction 43 Correlative conjunction 43 Demonstrative pronoun 35 Homophone 45 Indefinite pronoun 36 Interjection 44 Interrogative pronoun 36 Noun 34 Personal pronoun 35 Possessive pronoun 35 Preposition 42 Pronoun 34 Reflexive pronoun 35 Relative pronoun 35 Subordinating conjunction 43 Verb 37 04/11/11 11:57 AM