* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download MacroPolicy - Purdue Agriculture

Foreign-exchange reserves wikipedia , lookup

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Nominal rigidity wikipedia , lookup

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup

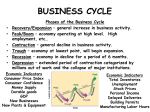

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Modern Monetary Theory wikipedia , lookup

Real bills doctrine wikipedia , lookup

Helicopter money wikipedia , lookup

Exchange rate wikipedia , lookup

Great Recession in Russia wikipedia , lookup

Fiscal multiplier wikipedia , lookup

Long Depression wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup