* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download convergence report 1998

Foreign-exchange reserves wikipedia , lookup

Modern Monetary Theory wikipedia , lookup

Inflation targeting wikipedia , lookup

Balance of payments wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Exchange rate wikipedia , lookup

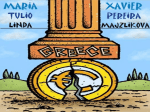

Pensions crisis wikipedia , lookup

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup