* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The supernova of AD1181 – an update

Survey

Document related concepts

Corona Australis wikipedia , lookup

Dyson sphere wikipedia , lookup

H II region wikipedia , lookup

Observational astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Chinese astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Aquarius (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Cygnus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Perseus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Cassiopeia (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Timeline of astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Stellar evolution wikipedia , lookup

Astronomical spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Star of Bethlehem wikipedia , lookup

Star formation wikipedia , lookup

Corvus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

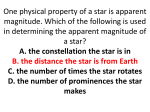

Supernovae The supernova of AD1181 – an update F Richard Stephenson and David A Green summarize observations of the supernova of AD 1181 in East Asia and recent observations of its remnant, 3C 58. O +80° +60° Kui Ziwe i 5h Chu gai ω e h +70° 3C 58 ψ tic eq uator ε 3C 10 δ h 3 rig ht ce as ion ns ν 1h following are translations of four key records, the first of which – noted by Li Jinyi – provides the most detailed information. Key records 1. South China. “In the 8th year, sixth month, day jisi [6 August AD 1181], a ‘guest star’ appeared in Kui lunar lodge. It was trespassing against Chuanshe. According to divination, the guest star was a star of ill omen ... (astrological commentary) ... The guest star appeared at the edge of Ziwei among the stars of Chuanshe ... (further astrological commentary) ... On the day jiaxu (11 August) the guest star guarded the 5th star of Chuanshe. In the 9th year, 1st month, day kuiyou [6 February AD 1182] the guest star disappeared. From the previous year, 6th month, day jisi until the present was a total of 185 days.” (Wenxian Toungkao – “Comprehensive History of Civilisation” by Ma Duanlin. Note: a summary of this account is to be found in the Songshu – “History of the Song Dynasty”.) 2. North China. “In the 21st year of the Ta-ting reign period, sixth month, day jiawu [11 August +60° β α Kui 1 Chart showing positions of stars, Chinese star groups, or “asterisms”, and the radio sources 3C 10 and 3C 58 in Cassiopeia. Asterisms marked with solid lines are following Shitong (1988), with the broken line indicating the less certain Chuanshe. The dotted green lines indicate the limits of the Chinese lunar lodge Kui. κ γ υ η θ 2h +80° Hua ι ansh galac 4 April 1999 Vol 40 6h E ast Asian observations of the star which appeared in AD 1181 were discussed by Stephenson (1971) and later by Clark and Stephenson (1977). These investigations led to the identification of the remnant of the star as 3C 58 (=G130.7+3.1). As pointed out by Li Jinyi (1983, paper in Chinese), a further Chinese record, not discussed in the above references, gives additional support to this identification. This record is also reported, briefly, in English, by Wang Zhenru (1987). In this paper we update the historical information and summarize recent observations of 3C 58. The new star which appeared in the late summer of AD 1181 attracted considerable attention in South and North China (which were then two independent empires) and in Japan. However, there are no known European or Arabic records. Occurring in the Cassiopeia region, the star was visible for about six months and then faded from sight. From the descriptions in Chinese and Japanese history, it is possible to obtain a good fix on the position of the star, but not to constrain its light curve in any detail. The declination +70° bservations of the supernova of 1181 were recorded independently at different locations in North and South China and Japan. These descriptions fix the position of the star, coincident with the radio source 3C 58, and indicate that it was visible for up to 186 days, although they do not give any detailed information useful for constructing its light curve. We discuss in detail a new historical record of the supernova, and recent observations of 3C 58 that reinforce its identification as the remnant of this supernova. ζ Wan gl iang 0h 1181] a guest star was seen at Huagai altogether for 156 days; then it was extinguished.” (Jinshu – “History of the Jin Dynasty”.) 3. Japan. “In the first year of the Yowa reign period, sixth month, 25th day [7 August 1181], a guest star appeared at the north near Wangliang and guarding Chuanshe.” (Meigetsuki – “Diary of the Full Moon” by Fujiwara Sadaie.) 4. Japan. “In the first year of the Yowa reign period, sixth month, 25th day [7 August 1181], at the hour xu [19 to 21 h] a guest star was seen at the north-east. (It was like) Saturn and its colour was purple [blue-red] it had rays. There had been no other example since that appearing in the third year of the Kanko reign period [i.e. AD 1006].” (Azuma Kagami – “History of the Kamakura Shogunate”.) Note that “asterism” has become a standard term to describe the numerous small Chinese constellations or star groups, to distinguish these from Western constellations. In points 3 and 4 above, Chinese terminology has been used for asterisms, and for the hour xu. In each instance the new star is described as 2.27 Supernovae a “guest star” (kexing); this is the usual oriental term for a star-like object. Neither of the Japanese records gives any indication of the period of visibility of the star. However, the two independent records from South and North China affirm a lengthy duration. As the supernova was circumpolar, it would never be close to the Sun, so that its duration of visibility would be determined by its faintness, and by the local weather conditions in South and North China. The Azuma Kagami seems to imply that the star was about as bright as the planet Saturn – i.e. among the brightest stars in the sky, but by no means a really brilliant object. The fact that the star “had rays” may merely indicate an optical effect caused by its brightness, being significantly brighter than the surroundings stars in Cassiopeia. Its lack of mention in Korea also suggests that it was not outstandingly bright. (Reference to the Koryosa shows that Korean astronomical records around this time are fairly detailed, but they all relate to meteors or lunar and planetary movements; there is nothing which could be understood to relate to a strange star of long duration). The supernova of AD 1006, with which the guest star was compared in Japan, was a brilliant object; however, this occurred nearly two centuries earlier so that no direct comparison could be made. Locating the observations The first of the records for which we have given translations indicates the approximate range of right-ascension (in Kui lunar lodge) within which the star appeared. This is a zone about 15° in width, extending north and south from Andromeda and Pisces. The asterism Ziwei (“Purple Palace”) was near the edge of the circle of perpetual visibility. Other asterisms near which the guest star appeared are Chuanshe, Wangliang and Huagai. These are neighbouring asterisms in Cassiopeia and lie near the galactic plane. Comparison between early oriental star maps and detailed modern charts shows that Wangliang, a group of five stars named after a famed charioteer, includes some of the brightest stars of Cassiopeia. Although much fainter, the seven stars of Huagai (“Gilded Canopy”) form a well-defined cluster shaped like a parasol and are fairly readily identified. Chuanshe (“Inns”, “Guest Houses”) is an extended asterism consisting of nine dim stars barely visible to the unaided eye and extending more or less along an east–west direction. It lies roughly midway between Wangliang and Huagai. Clearly the most detailed record is that from South China which asserts that the guest star “guarded the 5th star of Chuanshe”. It is interesting that the account in the Meigetsuki also notes that the guest star “guarded” this same asterism; the term implies a stationary 2.28 position. According to the extensive historical researches of the Beijing astronomer Yi Shitong (1988), the fifth constituent of Chuanshe is a faint star quite close to ε Cas. A long period of visibility and proximity to the galactic equator are both characteristic of supernovae. Of the known supernova remnants (SNRs) which have been identified, only two which are relatively young lie in this part of the sky. One of these remnants is 3C 10 (=G120.1+1.4), but this is well established as the remnant of the supernova which appeared in AD 1572. The careful measurements of Tycho Brahe and other European observers in 2: Radio emission from 3C 58 at 2.7 GHz observed with the Cambridge 5 km telescope. This is the remnant of the supernova of AD 1181, and is ~9 × 5 arcmin square. that year leave no doubt as to this identification (see the discussion in Clark and Stephenson 1977). The other remnant is 3C 58 (=G130.7+3.1). Allowing for precession, a star with this location would lie close to the eastern edge of the lunar lodge Kui and roughly between Wangliang and Huagai (see figure 1). Further, it would be very near to ε Cas – in accord with Yi Shitong’s identification. Hence there is remarkable accord between the recorded position of the star and that of the supernova remnant 3C 58. The identification of 3C 58 as the remnant of the supernova of AD 1181 has not always been accepted, mainly because of discrepancies between the distance estimates available for the source of ~3 and ~8 kpc. At the larger distance it would be difficult to reconcile the physical size of 3C 58 with an age of only around a thousand years. However, the smaller distance – which was first proposed by Green and Gull (1982) from neutral hydrogen (21 cm) line observations – has been confirmed by more recent 21 cm observations by Roberts et al. (1993). These authors also confirmed that confusion with structure in hydrogen emission was responsible for apparent absorption features that had led to the erroneous larger distance. Like the Crab nebula, 3C 58 shows a centrally brightened morphology at radio (see figure 2) and X-ray wavelengths, and this is generally taken to be an indication of the presence of a central, compact energy source in these objects. However, unlike the Crab nebula, 3C 58 does not have a pulsar definitely identified within it as its central power source, although there is evidence for a central compact source from X-ray observations (Helfand, Becker and White 1995). The Crab nebula and 3C 58 are both members of the “filled-centre” class of SNRs, which contains about 10 known objects in the Galaxy, all of which show such centrally brightened morphologies. (These SNRs are also called “Crab-like” remnants, although it is not clear whether or not the Crab is typical.) These “filled-centre” SNRs are also characterized by their flat radio spectra, with spectral indices α of ≈0.0 to 0.3 – where flux density S varies with frequency υ as S ∝ υ–α – in contrast to typical spectral indices of 0.4 to 0.6 seen on the majority of SNRs, which are of “shell” type. In the shell remnants the relativistic particle spectrum responsible for the observed radio is thought to be due to shock acceleration, whereas the particle spectrum from the central sources in “filled-centre” SNRs clearly must be much harder. Recently it has become clear that not only is 3C 58 much less luminous than the Crab nebula, despite being about the same age, but also that (see Green and Scheuer 1993 or Woltjer et al. 1997) the form of its synchrotron spectrum is quite different from that of the Crab. The flat radio spectra of the Crab nebula extends from the radio through to the optical, with a spectral break at ~104 GHz. On the other hand, the upper limits on the infrared emission from 3C 58 that are available from IRAS imply that 3C 58’s spectrum turns over sharply somewhere near 50 GHz. This implies that either the intrinsic spectrum produced by the central power source in 3C 58 is quite different from that produced by the pulsar in the Crab nebula, or that the break is produced by synchrotron losses, and the central source in 3C 58 has not been active for some considerable time. Crucial to this interpretation of 3C 58’s present-day synchrotron is the fact that the age of 3C 58 is known from the historical observations of its parent supernova. ● F R Stephenson, Department of Physics, University of Durham and D A Green, Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge. References Clark D H and Stephenson F R 1977 The Historical Supernovae Pergamon, New York. Green D A and Gull S F 1982 Nature 299 606. Green D A and Scheuer P A G 1992 MNRAS 258 833. Helfand D H, Becker R H and White R L 1995 ApJ 453 741. Li Jinyi 1981 Studies in the History of Natural Sciences 2 45 (in Chinese). Roberts D A et al. 1993 A&A 274 427. Stephenson F R 1971 QJRAS 12 10. Wang Zhenru 1987 in The Origin and Evolution of Neutron Stars (IAU Symposium No.125), eds Helfand D J and Huang Jiehao, p305 (Reidel, Dordrecht). Woltjer L et al. 1997 A&A 325 295. Yi Shitong 1988 Atlas comparing Chinese and Western Starmaps and Catalogues (Science Press, Beijing) (in Chinese). April 1999 Vol 40