* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Classical

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

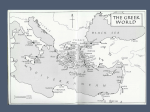

Ancient Greek Sculpture All rights reserved. Rights belong to their respective owners. Available free for non-commercial and personal use. First created 15 Mar 2012. Version 1.1 - 5 Apr 2012. Jerry Tse. London. Cycladic 2500-2000 BCE The story of Greek sculpture began around 4000 years ago in the Greek islands, where they made simple white marble models of gods and goddesses. Minoan 1700-1500 BCE There were few statues found in Minoan Crete. This is the ‘Snake Goddess’ found in a family shrine. Mycenean There was no sculpture found in Mycenae. This female painted plaster head is believed to be the head of a sphinx. Archaic 700-500 BCE This statue was amongst some of the earliest Greek statue. It depicted an archaic goddess. Statues at this time were stiff, unlike those of Ancient Egypt and often carried an Archaic smile. The Lady of Auxerre. 650-625 BC. 75 cm. Limestone. Archaic. Cretan. Musee du Louvre. Archaic Most of the sculptures were created primarily for the purpose of idol worships. Most were less than life-size. Demeter, goddess of fertility on a throne. 6C BC. Terracotta. Archaic. Cretan. Found in Grammichele, Sicily. Funeral markers begin to appear in Greece. The similarity with the Egyptian sculpture can be seen here. But the Greek sculpture carries a smile and the genital is clearly shown. The Greek statue is slightly larger than life-size. Archaic By the Middle Archaic period from 580 BC – 535 BC, attentions were shifted to kouros and kore sculptures of young men and women, with emphasis on bodily beauty but the poses were still stiff and conformed to stereotypes. Archaic Kore. 530-520 BC. Marble. Height 2.01 m. Archaic. Acropolis Museum Athens. Archaic Unlike her male counterpart, she is fully dressed, with elaborate drapery and hair style. She still carries the archaic smile. Kore (no 680). 530-520 BC. Marble. Archaic. Acropolis Museum Athens. Archaic This was an unusual subject matter, showing a man from Attic, who came to Athens to make a sacrificial offer of a calf to the goddess. It is a pleasing sculpture with the calf gently carried on the shoulder of the owner. The Calf-Bearer (The Moschophoros). 570 BC. Marble. Height 1.65m. Archaic. Acropolis Museum Athens. Archaic Wounded Warrior from Temple of Aegina. C490-480 BC. Marble. Length 1.78m (Life-size). Late Archaic. On the East Pediment of Aegina Temple. Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich. Archaic The arrival of the Severe Style marked the beginning of the end of the Archaic style. Greek society underwent a transformation to become a leading civilisation in the eastern Mediterranean. During this time, the Mediterranean markets were flooded with Greek pottery. Schools of philosophy were flourishing. The city of Athens was in the ascent. Greek art was changing. The Athena of Aegina, wearing a helmet. c460 BC. Aeginetan. Greek. Musee du Louvre. Archaic This is a well proportioned and beautifully sculpted Kore, in severe style. It is called ‘sulky’ because she does not carry the Archaic smile. Carved by the same artist who made the Kritios Boy (on a later slide). The Sulky Kore. 480 BC. Marble. Height 1.65m. Archaic. Acropolis Museum Athens. Classical 480-336 BCE The concept of beauty was an expression of the inner beauty. Artists used their power of observation, created even more naturalistic sculptures with increasing details. Blond Boy. 480 BC. Marble. Acropolis Museum Athens. Classical. Classical Kritios Boy or Critin Boy marked the emergence of a new sculptural style, the Classical style. The proportion of the boy’s torso was near perfection, with life-like accuracy. Sculptures began to shift away from the stiffness of the archaic style to a more life-like posture. The weight of the sculpture was supported by the left leg, while the right leg was bent at the knee. The spine acquired an “S” curve and the shoulder line dipped to the left to balance the action at the pelvis. Classical These ‘movements’ were achieved by dividing the body into four main sections. The arms and the legs were bent independently. The body above the waist was twisted to produce a more natural posture. Ares Borghese. 5C BC (Roman copy). Marble. Classical. Height 2.1m. Musee du Louvre. The two horses’ heads summarised the advances made by the Classical Greek. The horse of Selene (above) had just pulled the chariot of Selene across the sky. It was absolutely exhausted, with bulging eyes. Its veins were clearly visible, with opened mouth and nostrils enlarged, grasping for air. Horse head. Archaic Style from the Acropolis Museum, Athens. Classical Horse head of Selene from the pediment of the Parthenon, Athens. 447-432 BC. British Museum, London. Classical On the tympanum of the Temple of Marasa. Late 5C BC, Marble. National Museum of Reggio di Calabria Classical The statue was offered by a tyrant of Gela (Sicily) to the Delphic sanctuary to commemorate his victory in the chariot race at the Games. The Charioteer of Delphi. 474 or 478 BC. Bronze. Height 180cm. Classical. Delphi Museum. Classical The original was made by Myron Classical Bronze head of Apollo (?), found in the Tamassos, Cyprus. 470-460 BC. Bronze. Classical. British Museum. Classical An exceptional bronze with arms fully extended, an achievement showing the advance made by only a generation of sculptors later, since the austere Archaic style. Artemision Bronze (Zeus or Poseidon). 460 BC. Bronze. Height 2.1m Classical. National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Classical Classical Two full size bronzes of exceptional quality were found in 1972 off the coast of Italy. They are known as the Riace Bronzes. Classical The Riace Bronzes Classical The Riace Bronzes had gone beyond the depiction of life-like proportions, as in the Kritios Boy. The grove in the back was exaggerated to show a ‘an ideal’ body form. Classical Philosopher of Porticello. 420-410 BC. Bronze. Classical. Museo Archaeologico Nazional di Reggio Calabria. Classical Pericles was a prominent Athenian statesman, who successful created the Athenian Empire. Bust of Pericles. c430 BC. Marble. Classical. Vatican Museum, Rome. Classical Classical Praxiteles was a well-known 4C BC sculptor. Hermes Farness. Roman copy of a c325 BC sculpture. Marble. Height 2.01m. Classical. Original by Praxiteles. Greek. British Museum. Classical Praxiteles was the first to sculpt the nude female in life -size statue. Classical Aphrodite or Venus Classical Dancing Satyr. Roman copy of a 4C BC statue. Marble. Attrib to Lysippus. Classical. Greek. Galleria Borghese, Rome. Hellenistic 336-146 BCE With the arrival of Alexander the Great, Greek sculptors had taken their art to another level of realism and exaggeration. Their sculptures became even more expressive. The head showed a new level of realistic individualized features, with a hint of an emotional expression. The Bronze Head of Delos. Mid-Late 2C BC. Bronze. Hellenistic. Greek. National Archaeological Museum Athens. Classical The bronze was found in Olympia, sculpted by Silanion. It is an exceptional piece, showing the battered bruised face of a boxer, marked by swellings and wrinkles. Head of a Boxer. 330-320 BC. Bronze. Hellenistic . Greek. National Archaeological Museum Athens. Hellenistic Sleeping Hermaphrodite, showing the female (top) as well as the male side (bottom). Roman copy of a 2C BC Greek sculpture. Marble. Hellenistic . Greek. Musee du Louvre. Hellenistic Hellenistic This is the story telling sculpture of Laocoon with its exaggerated feeling of pain. Laocoon & His sons. Roman copy of a 175-150 BC sculpture. Marble. By Agesander, Polydorus and Athenodorus of Rhodes. Hellenistic . Greek. Vatican Museum, Rome. Hellenistic Hellenistic Winged Victory of Samothrace. c190 BC. Marble. Span 3.3m. Hellenistic . Greek. Muses du Louvre, Paris. Hellenistic Hellenistic The Greek sculptors extended their expressive portrait of human to animals. Only five Roman copies of this Greek bronze are known to exist. Molossian Hound. Probably 2C BC. Marble. Hellenistic . Greek. British Museum, London. Hellenistic Venus de Milo. c120 BC. Marble. Height 2.02m. Alexandros of Antioch. Hellenistic . Greek. Musee du Louvre, Paris. Hellenistic Lely’s Venus (Aphrodite Crouching at her Bath). Roman copy of 1C BC Greek original. Marble. British Museum, London. Hellenistic Lely’s Venus (Aphrodite Crouching at her Bath). Roman copy of 1C BC Greek original. Marble. British Museum, London. Amongst the ancient civilisations of the world, only the Greek had produced such naturalistic and life-like sculptures. Some 1500 years later, with the arrival of Michelangelo, these sculptures were finally surpassed. The End All rights reserved. Rights belong to their respective owners. Available free for non-commercial and personal use. Music – Zobra, the Greek composed by Mikis Theodorakis.