* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download PPT - University of Kent

Mentally ill people in United States jails and prisons wikipedia , lookup

Health psychology wikipedia , lookup

Subfields of psychology wikipedia , lookup

Occupational health psychology wikipedia , lookup

Community mental health service wikipedia , lookup

Lifetrack Therapy wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Equine-assisted therapy wikipedia , lookup

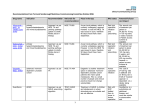

They’re NICE and neat but are they useful? A grounded theory of clinical psychologists’ beliefs about, and use of NICE guidelines. A DClinPsychol research project by Alex Court, 3rd year Trainee Clinical Psychologist. Supervised by Anne Cooke, Canterbury Christ Church University and Dr Amanda Scrivener, KMPT. • Why do we need to conduct research into the use of NICE guidelines in mental health services? NICE Aims • To improve clinical effectiveness and reduce variations in practice across NHS Trusts (DH, 1998). Not so NICE Implementation • Consistent reports that uptake of NICE guidelines in UK mental health services is low. (e.g. Lewis et al., 2012; Mankiewicz & Turner, 2012; Mears et al., 2008; Prytys et al., 2011; Evaluation and Review of NICE Implementation Evidence (ERNIE) database – “Doubts about or mixed impact in practice” / “Practice appears not to be in line with guidance”) Conflicting Views •“The way in which they have been developed and presented should be such that few recipients would ever have cause to dispute the basis of the recommendations.” (Littlejohns, 2000). •“NICE guidelines are misleading, unscientific, and potentially impede good psychological care and help.” (Mollon, 2009) • Berry and Haddock (2008) highlighted the paucity of research into factors affecting the use of NICE guidelines in UK mental health services and stressed the need for such research. • In relation to NICE guidelines for mental health conditions, research has investigated adherence to guidelines by: – GPs, (Gyani et al., 2011; Gyani, et al., 2012; Toner et al., 2010), – care co-ordinators (Prytys et al., 2011; Sin & Scully, 2008), – CMHT staff (Michie, et al., 2007; Rhodes, et al., 2010), – psychiatrists and paediatricians (Kovshoff et al., 2012) and – counselling psychologists (Hemsley, 2013). My Study •Interviewed 11 clinical psychologists. •Grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) was utilised to guide the data collection and analysis. •Aimed to develop a theoretical model, conceptualising the clinical psychologists’ beliefs, decision making processes and clinical practices. Results Overall Emerging Theme: “Considering NICE guidelines to have benefits but to be fraught with dangers.” Considering NICE guidelines to have benefits but to be fraught with dangers Recognising the context of the current economic climate Valuing the benefits of NICE guidelines Plus Influences Worrying that NICE guidelines can create an unhelpful illusion of neatness Plus Influences Beliefs about the purpose of, and future of clinical psychology Perceived level of pressure to be NICE compliant Leads to Having a flexible relationship with guidelines Impacts upon Impacts upon Key Points • Guidelines were seen as a useful guide to the evidence base. • The power of NICE endorsement was valued. • The CPs worried that guidelines could easily be misunderstood and used in a rigid and limiting manner. • CPs managed the tension between the helpful and unhelpful aspects of guidelines by relating to them in a flexible manner. • There were concerns about the harm that misuse of guidelines could do to service users and also to the profession of clinical psychology. Beliefs About the Purpose of & Future of CP • A difficult fit between the actual practice of CPs and the language of NICE. – Diagnosis vs formulation. – Manualised therapy vs idiosyncratic, collaborative, integrative approaches. • As a result of pressure, and also the rewards that follow from being seen to comply with NICE guidelines, they tended to practice in ways that prevent these skills from being recognised. • “Well I, well I certainly wouldn't advertise what I do to the managers.” (Amy). • “I would probably say I’m doing CBT, even if I’m not doing, you know, even if it’s a bit fudgy around the edges.” (Jenny). • “You can integrate – I quite often make use of psychodynamic or systemic ideas which I might, you know, bring into my CBT work…which I think is perfectly fine within a CBT model. I mean you’re talking about thoughts and feelings and you’re talking about it in an interpersonal context.” (Sam). Threat to Professional Identity • Why train CPs in a variety of therapeutic models if the “illusion” is that CBT is all that is practiced? • Why do we need CPs at all if services only need CBT therapists? Conclusions • CPs need to improve the way that they advertise their specialist skills. • This is the first theoretical framework that attempts to explain why NICE guidelines are not consistently utilised in UK mental health services. • Attention is drawn to the proposed benefits and limitations of guidelines and how these are managed. Final Thoughts on Guidelines • A common conclusion from the participants was wanting NICE to be viewed as guidelines and not instructions. • The CPs wanted NICE guidelines to be seen as a work in progress with numerous limitations. “I think it deserves further research. So perhaps I would say that I’m not sure that it (NICE) should be there, I’m not sure it shouldn’t be there. I think it needs to be absolutely reviewed.” (Jan). [email protected]