* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Eurosurveillance Weekly, funded by Directorate General Health and

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Tuberculosis wikipedia , lookup

Poliomyelitis wikipedia , lookup

Sexually transmitted infection wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Poliomyelitis eradication wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Mass drug administration wikipedia , lookup

Whooping cough wikipedia , lookup

Plasmodium falciparum wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

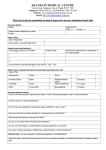

Eurosurveillance Weekly, funded by Directorate General Health and Consumer Protection of the European Commission, is also available on the world wide web at <http://www.eurosurv.org>. If you have any questions, please contact Birte Twisselmann <[email protected]>, +44 (0)20-8200 6868 extension 4417. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf is liable for any use made of the information published here. Eurosurveillance Weekly: Thursday 5 January 2001. Volume 5, Issue 1 Contents: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 infection in Spain Infections among injecting drug users in Norway, 1997-2000 Concern about polio vaccine distributed in the Republic of Ireland Risk of measles and pertussis associated with exemption from vaccination Malaria in Austria, 1990-9 Outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 infection in Spain One hundred and eighty-one cases have been reported in the largest outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection yet identified in Spain. The cases are 150 schoolchildren at four schools in Barcelona and 31 household contacts. Cases became ill between 19 September and 5 November 2000. Six children developed haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), but all recovered. The attack rates in the four affected schools ranged from 4% to 56%. Preliminary enquiries suggested that the vehicle of infection was sausage served by a catering company on 18 September 2000. The catering company supplied 10 schools, one factory, and a home for elderly people. Cases arose at schools where the sausages were not heated; at the remaining schools the sausages had been heated. Inspection of the catering company identified irregularities and the company was closed down. No food samples were investigated. E. coli O157:H7 was isolated from 27 cases, and eight isolates were shown to be phage type 2. This is the seventh outbreak of E. coli O157 infection to have been reported to the National Centre of Epidemiology in Spain since 1989. The next largest affected tourists from several countries who had visited the Canary Islands in 1997 (1): 14 cases were confirmed in tourists, and three developed HUS. In Spain, surveillance of E. coli O157 infection is undertaken by the Microbiological Information System (SIM), a voluntary laboratory based system, and by the National Reference Laboratory, which contributes to Enter-net. E. coli O157 infection is not a statutorily notifiable disease in Spain, but it is obligatory to notify all outbreaks. In the past 10 years, only 41 and 12 cases have been reported to both surveillance systems, respectively (2). References 1. Pebody RG, Furtado C, Rojas A, McCarthy N, Nylen G, Ruutu P, et al. An international outbreak of Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 infection amongst tourists; a challenge for the European infectious disease surveillance network. Epidemiol Infect 1999; 123: 217-23. 2. Soler P, Hernández G, Mateo S. Vigilancia de Escherichia coli O157 en España. Boletín Epidemiológico Semanal 1999; 7:105-6. Reported by Ana Martínez ([email protected]), Josep María Oliva, Departamento de Sanidad y Seguridad Social de la Generalidad de Cataluña; Elena Pañella, Instituto Municipal de Salud Pública. Ayuntamiento de Barcelona; Gloria Hernandez-Pezzi (ghrnandz.isciii.es), Pilar Soler ([email protected]), Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Madrid, Spain. Infections among injecting drug users in Norway, 1997-2000 The number of infections among injecting drug users (IDUs) reported to the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases (MSIS) has risen in the past five years. In 1999 infections among identified drug users constituted 9% of all cases notified to MSIS. This high proportion is due mainly to national outbreaks of hepatitis A and hepatitis B in drug using communities between 1995 and 2000. In addition, rarer conditions such as anthrax, wound botulism, and clostridial infections have been seen among IDUs. Most of these infections are thought to be associated with intramuscular and subcutanous injection by so-called ’skin poppers’. There is no registration of people using illegal drugs in Norway. Estimates of the number of drug users who inject substances are therefore made by indirect methods. Based on reports from police and social services, the National Institute of Alcohol and Drug Research has estimated that in the 1990s the number of active IDUs in Norway has increased from 4000-5000 in 1990 to 10 000-14 000 in 1999. In the same period, the price of illegal drugs fell considerably, and the number of drug seizures by the police increased for all kinds of narcotics. Both these factors indicate an increased supply of illegal drugs. Infections among identified drug users notified to MSIS: 1997-2000 Infection Hepatitis A Hepatitis B Hepatitis C (acute) Hepatitis D Hepatitis B (chronic carriers) HTLV II infection HIV infection AIDS Pneumococcal serious invasive disease Streptococcal serious invasive disease, group A Wound botulism Anthrax Clostridium novyi infection Total Figures for 2000 are preliminary. 1997 150 135 13 1 38 1 11 8 2 6 1998 278 385 17 1 40 0 7 4 1 7 1999 532 374 15 4 29 2 11 3 3 5 2000 16 155 13 0 27 2 6 0 2 3 3 368 0 740 0 978 1 1 1 227 Hepatitis National outbreaks of hepatitis A and hepatitis B among drug addicts started in 1995. The hepatitis A outbreak declined at the end of 2000, but large numbers of cases of hepatitis B are still being reported among IDUs. In the five years from 1995 to 2000, 1353 cases of hepatitis A and 1136 cases of hepatitis B among drug users were notified. A number of drug users had serological indicators of both infections and hepatitis C. Not all infected drug users seek medical care, and reports of cases of hepatitis do not always indicate whether the patient takes drugs. The reported cases among drug users must therefore be regarded as a minimum estimate of the actual cases. In Norway, only symptomatic acute hepatitis C or known seroconversions are notifiable, and reported cases of hepatitis C do not reflect the true incidence. Several prevalence studies have shown that 50% to 80% of drug addicts have antibody to hepatitis C virus. HIV infection In spite of the extensive risk behaviour among drug addicts evident from the hepatitis A and hepatitis B outbreaks, the number of addicts diagnosed with HIV infection has remained low, with about 10 new cases each year. Most patients with hepatitis have also been tested for HIV. Tuberculosis In contrast to many other European countries, tuberculosis among drug users and homeless people is diagnosed rarely in Norway, and no outbreaks among drug users have ever been reported. For several years, health authorities in Oslo have been screening drug communities for tuberculosis by use of mobile radiological equipment. Twenty-two of 642 addicts examined in the autumn of 2000 needed follow up on the basis of radiological findings. To date, tuberculosis has been diagnosed in only one of these. Wound botulism Four sporadic cases of wound botulism among IDUs have been reported in Norway since 1997 (1). The last case was reported in 2000 (2). Other bacterial infections The first ever case ever of anthrax transmitted by injection was diagnosed in Oslo in the spring of 2000 (3). This was an isolated case and is thought to have been caused by contaminated heroin. Clostridium novyi was isolated from a drug addict in Oslo who was suffering serious systemic disease (4). This case was probably related to the outbreak of severe systemic sepsis associated with soft tissue inflammation in the British Isles (5). An investigation of the heroin used by the patient is under way. Skin infections and abscesses are not unusual in drug addicts and may develop into more serious, toxic conditions. Such cases are probably underreported to MSIS. Preventive measures Since 1997 vaccines against both hepatitis A and hepatitis B have been offered free of charge to all drug users (not only IDUs) in Norway. Local health authorities all over the country have been encouraged to promote such vaccination in drug communities whether local outbreaks have occurred or not. Information for and vaccination of newcomers in drug communities is particular important. In addition, many localities have taken steps to provide clean syringes and other user equipment. Drug addicts have been warned through news media and the local health and social services against injecting narcotics intramuscularly or subcutaneously and to seek medical care if skin abscesses develop. References: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Kuusi M, Hasseltvedt V, Aavitsland P. Botulism in Norway. Eurosurveillance 1999; 4: 11-2. (http://www.ceses.org/eurosurv) Jensenius M, Løvstad RZ, Dhaenens G, Rørvik LM. A heroin user with a wobbly head. Lancet 2000; 356: 1160. Ringertz SH, Høiby EA, Jensenius M, Mæhlen J, Caugant DA, et al. Injectional anthrax in a heroin skin-popper. Lancet 2000; 356: 1574-5. A Maagaard, N Hermansen, B Heger, M Bruheimand, N K Meidell, T Hoel, et al. Serious systemic illness among injecting drug users in Europe: new case in Oslo. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2000; 4: 000803. (http://www.eurosurv.org/2000/000803.htm) Andraghetti R, Goldberg D, Smith A, O’Flanagan D, Lieftucht A, Gill N. Severe systemic sepsis associated with soft tissue inflammation (previously reported as ‘serious unexplained illness’) in injecting drug users in Scotland, Ireland, England, and Wales. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2000; 4: 000803. (http://www.eurosurv.org/2000/000803.htm) Reported by Hans Blystad ([email protected]), Øivind Nilsen (mailto:[email protected]) and EA Høiby ([email protected]), National Institute of Public Health, Oslo; T Hoel ([email protected]), Chief Medical Officer, Oslo. Based on MSIS-rapport 2000; 28: 48. Concern about polio vaccine distributed in the Republic of Ireland The Republic of Ireland’s Department of Health and Children has been informed that one blood donor from the United Kingdom, plasma from whose donation was used in Britain to make a batch of the product human serum albumin, has recently been diagnosed with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) (1,2). This person's donation was one of 22 353 used to make a pool, which was combined with another pool to give a final dilution of 1/63 866. This human serum albumin was used by Evans/Medeva in the manufacture of oral polio vaccine, as an essential stabilising agent. Some 83 500 doses of this polio vaccine were distributed in Ireland between 15 January 1998 and 30 January 1999. More detailed checking is taking place with Ireland’s health boards to establish the precise usage of this vaccine. It is regarded as unwise in medicine to say that a risk is absolutely zero, but expert advice (both national and international) available to the Department of Health and Children indicates that in this situation this is almost certainly the case. Albumin has a good safety record. It is produced at the last stage of a series of purification procedures, which eliminate the potential for infectivity. Recent studies of the various plasma fractions have shown no infectivity associated with albumin. Polio vaccine is administered to children in the Republic of Ireland as part of the primary childhood immunisation programme at the ages of 2, 4, and 6 months, and a booster immunisation is given at primary school entry age. Some adults may also have received the vaccine as part of the recommended immunisations for travel to certain countries. Plasma material sourced from the United Kingdom is no longer contained in any vaccine used in Ireland (3). Parents are advised to continue with the normal childhood vaccination programme. References: 1. 2. 3. Department of Health and Children. Minister Martin issues statement about polio vaccine distributed in 1998/9. Press release, 19 December 2000. (http://www.doh.ie/pressroom/pr20001219.html) Oral polio vaccine statement. Epi-Insight 2001; 2: 4. (http://www.ndsc.ie/epi_insight/0101ei.pdf) Irish Medicines Board. Frequently asked questions about the oral polio vaccine and a vCJD donor. IMB news, 19 December 2000. (http://www.imb.ie/updates%2021.12.2K/faq.pdf) Risk of measles and pertussis associated with exemption from vaccination A study reported in JAMA last week quantified the risk of measles and pertussis in children whose parents had signed personal exemption statements (1). The study, carried out in Colorado, compared reports of the two diseases in children aged 3 to 18 years – vaccinated and exempted on religious or philosophical grounds - between 1987 and 1998. The frequency of religious exemptions fell slightly between 1987 and 1998 – from 0.23% to 0.19% - while philosophical exemptions nearly doubled (from 1.02% to 1.87%). Exemptors were 22 times more likely than vaccinated children to acquire measles (confirmed cases) and six times more likely to acquire pertussis (confirmed and probable cases). When the data were analysed by county, controlling for confounding variables (income, education, immigrant population, and population density) the incidence of measles and pertussis in vaccinated children was shown to be associated with the frequency of exemptors. Schools where pertussis outbreaks had arisen had higher proportions of exemptors than schools without such outbreaks (4.3% compared with 1.5%) and at least 11% of vaccinated children who developed measles in outbreaks acquired measles through contact with an exemptor. The authors discuss the limitations and strengths of their data, but warn of the risks that can arise when too many parents exempt their children from vaccination, relying on the herd immunity of other members of the community. An accompanying editorial considers the use in the United States of legal measures to ensure high levels of vaccine coverage (2). A large outbreak of measles associated with low vaccine coverage attributable to religious objections was reported in the Netherlands in 1999 and 2000 (3). In the United Kingdom outbreaks of measles have occurred in orthodox Jewish communities and in Rudolf Steiner communities (4). A large outbreak of measles in the Republic of Ireland appears to have been due to low vaccine coverage due to neglect rather than intent, and was controlled by a vaccination awareness campaign (5,6). References: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, Salmon DA, Chen RT, Hoffman RE. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. JAMA 2000; 284: 3145-50. (http://jama.ama-assn.org/issues/current/rpdf/joc01122.pdf) Edwards KM. State mandates and childhood immunization. JAMA 2000; 284: 3171-3. (http://jama.ama-assn.org/issues/current/fpdf/jed00093.pdf) van Steenbergen J. Measles in the Netherlands: update. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2000; 4: 000106 (http://www.eurosurv.org/2000/000106.html) McCann R, van den Bosch C, White J, Cohen B. Outbreak of measles in an Orthodox Jewish community. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2000; 4: 000119 (http://www.eurosurv.org/2000/000119.html) Cronin M, O’Connell T. Measles outbreak in the Republic of Ireland: update. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2000; 4: 000420 (http://www.eurosurv.org/2000/000420.htm) Cronin M, Fitzgerald M. Measles outbreak in the Republic of Ireland: update. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2000; 4: 000914 (http://www.eurosurv.org/2000/000914.htm) Reported by Stuart Handysides ([email protected]), Eurosurveillance editorial office Malaria in Austria, 1990-9 Between 1990 and 1999, 862 cases of malaria were imported into Austria (range 58 in 1992 to 113 in 1990), according to Mitteilungen der Sanitätsverwaltung (1). An average of 84 cases was reported each year, and no increasing or decreasing trend was observed (P>0.05). The total population of Austria is 8.1 million. No details about the incidence can be given as the numbers of people travelling into endemic regions each year are not made available by tour operators. Fifty-six per cent of cases (479) were infected with Plasmodium falciparum, 36% (308) with P. vivax/ovale, 4% (34) had a mixed infection (causative agent not documented), and 2% (16) were infected with P. malariae. The causative agent of 25 cases (3%) was not documented. Cases of P. falciparum in the total number of cases formed a significantly higher proportion over the years (P<0.001), although the increase variable was comparatively small (ß=0.13). Non-parametric models also showed a positive trend. The World Health Organization classifies areas endemic for malaria as A (a generally low and season linked risk), B (low to middle risk), and C (high risk). Most infections occurred in travel region C (635; 74%), followed by B (162; 19%) and A (37; 4%). In 28 cases the region travelled was not known. If every strain is analysed separately, most infections occurred in high risk areas (P. falciparum 87%, P. vivax/ovale 51%, 87% P. malariae 87%, mixed infection 70%, unknown strain 72%). The likelihood of contracting falciparum malaria was significantly higher in regions with a low to middle and high risk than in regions with a generally low and seasonal risk (region B: odds ratio 6.3, 95% confidence interval 4 to 9.1, P<0.001; region C: OR 13.64, 4.9 to 40.5, P<0.001). Stratification by age became possible in 1995, when the dates of birth of all cases of malaria began to be notified. Forty-six per cent (193/416) of cases from 1995 to 1999 were aged 31 to 45 years. Eight per cent (35) of all cases were children and young people aged up to 15 years, and half of those (18) were aged 5 years or younger. Eleven of the children aged under 5 years were infected with P. falciparum, and all except for one child had stayed in region C. An average of four children were notified each year; no increasing or decreasing trends were noticed. Five children were known to have taken chemoprophylaxis –three had taken mefloquine, one chloroquine, and one not known. Chemoprophylaxis Over half (358/691) of the malaria cases for whom data on chemoprophylaxis were available had taken drugs. Forty-three per cent (153) had taken mefloquine, and 35% (124) chloroquine, 4% (13) paludrine, 2% (6) Fansidar (pyrimethamine with sulfadoxine), and 17% (62) other, non-specified drugs. Almost half of those for whom data were available (333/691) had taken no chemoprophylaxis. Compliance No compliance data are available for 1990 and 1991. Between 1992 and 1999, 638 cases occurred, and compliance with a drug regimen was known for only 293 (46%) patients, 171 (60%) of whom had adhered to prophylaxis. Eighty-eight people (30%) had taken insufficient prophylaxis, and 29 patients (10%) had stopped their prophylactic regimen. Twelve patients died between 1990 and 1999. Between 1992 and 1996 no deaths occurred. Between 1995 and 1999 seven deaths were recorded, all were aged over 30 years. Three deaths were recorded in 1999. Nine (75%) had contracted falciparum malaria, one person each tertian malaria and one a mixed infection, and the causative agent in one person was unknown. Ten people who died had stayed in countries in region C (eight cases of falciparum malaria, one case with a mixed infection, one person with an unknown strain), one person in region B (tertian malaria) and in one person with falciparum malaria the country visited was not known. Compliance data were available for four people. Three had taken complete prophylaxis with an unknown antimalarial drug, and one person had stopped taking chloroquine. Among the reasons given for not taking chemoprophylaxis were unpleasant side effects, complicated regimens, and incorrect information provided by tour operators, pharmacists, or doctors. Motivation to take chemoprophylaxis needs to be encouraged by giving clear and comprehensive advice about transmission routes and dangers of malaria. As no chemoprophylaxis gives 100% protection, the need for preventing exposure by using insect repellents and mosquito nets and clothing impregnated with permethrin has to be stressed. In people who cannot take mefloquine, Malarone (proguanil hydrochloride with atovaquone) may be recommended. Malaria must be excluded in all people who present with fever within a year of returning from the tropics. Reference: 1. Strauss R, Pfeifer C, Siebinger G, Halbich-Zankl H. Malaria in Österreich 1990-1999. Mitteilungen der Sanitätsverwaltung 2000; 9: 9-16. Translated and adapted from reference 1 by Birte Twisselmann ([email protected]), Eurosurveillance editorial office.