* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Jason Moore, *Ecology, Capital, and the Nature of Our Times* (2011)

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

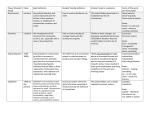

Jason W. Moore, ‘Ecology, Capital, and the Nature of Our Times: Accumulation and Crisis in the Capitalist World-Ecology’ (2011) Mike Davis, ‘Who Will Build the Ark?’ (2010) Dipesh Chakrabarty, ‘The Climate of History: Four Theses’. (2009) “For all its dogmatic and formulaic tone, Stalin’s passage captures an assumption perhaps common to historians of the mid-twentieth century: man’s environment did change but changed so slowly as to make the history of man’s relation to his environment almost timeless and thus not a subject of historiography at all.” Chakrabarty (204) “It is clear that the heat that burns the world in Arrighi’s narrative comes from the engine of capitalism and not from global warming.” (200) “Capitalism as world-ecology” – Background / theoretical context World-systems theory – Immanuel Wallerstein / Giovanni Arrighi David Harvey – “all social projects are ecological projects and vice-versa” The “Oregon School” – John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, Richard York; “metabolic rift” theory The Emergence of the World-System Concept “The originator of the current world-systems perspective is Immanuel Wallerstein, who argues in his book the Modern World-System, I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Econominy the Sixteenth Century (1974), that a world-system is a multicultural territorial division of labor in which the production and exchange of basic goods and raw materials is necessary for the everyday life of its inhabitants. It is thus by definition composed of culturally different societies that are vitally linked together through the exchange of food and raw materials.” (Chase-Dunn and Grimes, 1995: 389) Capitalism is a world-system that is also a world system Rise of the capitalist world-economy / world-ecology World-economy and world-ecology represent ‘distinct angles of vision onto a singular world-historical process’ “With the rise of capitalism, local societies were not integrated only into a world capitalist system; more to the point, varied and heretofore largely isolated local and regional socio-ecological relations were incorporated into – and at the same moment became constituting agents of – a capitalist world-ecology. Local socio-ecologies were at once transformed by human labour power (itself a force of nature) and brought into sustained dialogue with each other. [. . .] Hence, the hyphen becomes appropriate: We are talking not necessarily about the ecology of the world (although this is in fact the case today) but rather a world-ecology.” (Moore, “Capitalism as World-Ecology”, 2003: 447) Raymond Williams, “We have mixed our labour with the earth, our forces with its forces too deeply to be able to draw back and separate either out” “Labour is, first of all, a process between man and nature, a process by which man, through his own actions, mediates, regulates and controls the metabolism between himself and nature. He confronts the materials of nature as a force of nature. He sets in motion the natural forces which belong to his own body, his arms, legs, head and hands, in order to appropriate the materials of nature in a form adapted to his own needs. Through this movement he acts upon external nature and changes it, and in this way he simultaneously changes his own nature”. Marx, Capital, p. 283 “After a certain point, the Cartesian approach that identifies social causes and environmental consequences obscures more than it clarifies. Yes, capitalism has done many bad things to living creatures and the environments in which they live. Evidence can be collected and analyzed to document these depredations. [. . .] But so long as these studies operate within a Cartesian frame, the active relations of all nature in the making of the modern world remain not just unexplored, but invisible. The impressive documentation of environmental problems in the capitalist era is theoretically disarmed as a consequence, unable to locate the production of nature within the strategic relations of modernity.” Moore, p. 117 Moore “What would an alternative that transcends such Cartesian binaries look like? I propose that we move from the ‘environmental history of’ modernity, to capitalism ‘as environmental history.’” The oikeios (Theophrastus) – the “underlying relation” between human and extra-human relations that gives rise to ‘nature’ and ‘society’ “To take the Nature/Society binary as a point of departure confuses the origins of a process with its results. The plethora of ways that human and biophysical natures are intertwined at every scale – from the body to the world market – is obscured to the degree that we take nature and society as purified essences rather than tangled bundles of human- and extra-human nature.” p. 114 “capitalism does not develop upon global nature so much as it emerges through the messy and contingent relations of humans with the rest of nature.” p. 111 “Wall Street is a way of organizing nature” “an elusive logic of financial calculability rules the roost of global capitalism, and shapes, as never before, the structures of everyday life – including the ‘everyday lives’ of birds and bees and bugs” p. 136 “capitalism is constituted through a succession of ecological regimes that crystallize a qualitative transformation of capital accumulation – for instance the transition from manufacture to large-scale industry – within a provisionally stabilized structuring of nature-society relations.” Ecological revolutions and surpluses Ecological revolutions reorganize a particular configuration of nature-society relations so as to liberate accumulation after an ecological regime has stagnated Through a combination of productivity and plunder, they drive down the capitalized share of world nature and increase the share that can be freely appropriated They do this by expanding the relative ecological surplus, a surplus that finds its expression in the FOUR CHEAPS: 1. labour power; 2. food; 3. energy; 4. non-energy inputs such as metals, wood, and fibres. Chakrabarty: “In no discussion of freedom in the period since the Enlightenment was there ever any awareness of the geological agency that human beings were acquiring at the same time as and through processes closely linked to their acquisition of freedom.” (208) “Analytic frameworks engaging questions of freedom by way of critiques of capitalist globalization have not, in any way, become obsolete in the age of climate change. [. . .] Capitalist globalization exists; so should its critiques. But these critiques do not give us an adequate hold on human history once we accept that the crisis of climate change is here with us and may exist as part of this planet for much longer than capitalism or long after capitalism has undergone many more historic mutations. The problematic of globalization allows us to read climate change only as a crisis of capitalist management. While there is no denying that climate change has profoundly to do with the history of capital, a critique that is only a critique of capital is not sufficient for addressing questions relating to human history once the crisis of climate change has been acknowledged and the Anthropocene has begun to loom on the horizon of our present. The geologic now of the Anthropocene has become entangled with the now of human history.” (212)