* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

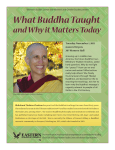

Download Bern Sat session 1 - The Foundation of Buddhist Thought

Buddhism and psychology wikipedia , lookup

Women in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Dhyāna in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Pre-sectarian Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Enlightenment in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddha-nature wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Western philosophy wikipedia , lookup

The Art of Happiness wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist philosophy wikipedia , lookup