* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Preview the material

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

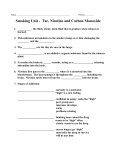

TOBACCO USE DISORDER AND SMOKING CESSATION ABSTRACT A tobacco use disorder is diagnosed according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and current research identifies tobacco patterns and severity of use that clinicians can reference when diagnosing and planning treatment. Medication and behavioral-based interventions such as direct provider to patient interaction, group therapy, specialized clinics, self-help interventions using educational resources and telephone resources or counseling are the mainstay of smoking cessation. Risk factors related to tobacco use, smoking cessation options and relapse prevention are discussed. Introduction Tobacco use and its attendant health consequences are enormous public health problems. Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States. The number of Americans who smoke has decreased by more than one-half in the past 50 years, but tobacco and cigarette smoking are still the primary causes of, or contributors to certain cancers, heart disease, common respiratory diseases, and many other acute and chronic pathology. Hundreds of thousand adults die prematurely each year as a direct result of smoking, and a 2014 report from the Surgeon General noted that tobacco and smoking have “ . . . killed ten times the number of Americans who died in all of our nation’s wars combined.”1 It has also ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 1 been proven that second-hand smoke is a significant cause of serious acute and chronic heath problems in children and adults. There are interventions that can prevent people from smoking and there are behavioral counseling techniques and medications that have been shown to be effective at helping smokers quit. But nicotine, the primary active component of cigarette smoke, is strongly addictive and since tobacco is legal the prevention of smoking and smoking cessation are considerable challenges. Smoking And Tobacco Use In The United States Smoking and tobacco use are still common in the United States. The statistics in Table 1 are from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association (SAMHSA).2-4 It should be noted that a current smoker is defined as a person who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes during his or her lifetime and, at the time the person participated in a survey about the topic, smoking every day or some days. Table 1: Smoking and Tobacco Use in the United States In 2014, almost 17 of every 100 U.S. adults aged 18 years or older (16.8%) currently smoked cigarettes. This means an estimated 40 million adults in the United States currently smoke cigarettes. There are also of millions of people who use smokeless tobacco and ecigarettes. Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States, accounting for more than 480,000 deaths every year, or 1 of every 5 deaths. More than 16 million Americans live with a smoking-related disease. Current smoking has declined from nearly 21 of every 100 adults (20.9%) in 2005 to nearly 17 of every 100 adults (16.8%) in 2014. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 2 In 2014, an estimated 66.9 million Americans aged 12 or older were current users of a tobacco product (25.2%). Young adults aged 18 to 25 had the highest rate of current use of a tobacco product (35%), followed by adults aged 26 or older (25.8%), and by youths aged 12 to 17 (7%). In 2014, the prevalence of current use of a tobacco product was 37.8% for American Indians or Alaska Natives, 27.6% for whites, 26.6% for blacks, 30.6% for Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders, 18.8% for Hispanics, and 10.2% for Asians. The incidence of tobacco use disorder (defined and explained in a subsequent section of this learning module) cannot be accurately determined, but given the common occurrence of nicotine craving and addiction it is clear that tobacco use disorder is widespread.5 As mentioned in the introduction, second-hand smoke (also called side stream smoke) is very dangerous. Second-hand smoke is smoke that is produced from burning tobacco or smoke that has been exhaled by someone using a cigarette and there is no safe level of second-hand smoke. The health effects of second-hand smoke that are listed in Table 2 are from the CDC and several other sources.6,7 Table 2: Health Effects of Second-Hand Smoke Asthma attacks Bronchitis COPD Ear infections Heart disease Lung cancer Pneumonia ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 3 Stroke Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) Second-hand smoke has been estimated to increase the relative risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke, and ischemic heart disease by 1.66, 1.35, and 1.22, respectively.8 Children are especially vulnerable to the harmful effects of second-hand-smoke7 and pre-natal exposure to second-hand smoke has been identified as a risk factor for developing asthma.9 Also, close proximity is not necessary for exposure to second-hand smoke; many studies have shown that living in a multi-residential building can expose nonsmokers to second-hand smoke.10 Smoking bans have reduced exposure to second-hand smoke in public areas but private homes are still an important source of second-hand smoke exposure. Nicotine Tobacco and tobacco smoke contain many harmful compounds but nicotine has been identified as the one that is primarily responsible for addiction to tobacco. Nicotine in cigarette smoke and in products such as chewing tobacco and snuff is rapidly absorbed across the alveoli and through mucous membranes. Nicotine can also be absorbed through certain sections of the gastrointestinal tract. Once nicotine has passed through the lungs, mucous membranes, or gastrointestinal tract it quickly enters the blood stream and then binds to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which are located in the central nervous ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 4 system, the autonomic nervous system, neuromuscular junctions, and other areas of the nervous system. The acute effects of nicotine depend on the dose and how habituated someone is to its effects. The amount of nicotine in an average cigarette is approximately 13-20 mg, but this “dose” is delivered somewhat slowly and the total absorbed and that reaches the central nervous system is much less. People smoke, in part, because the effects of nicotine are pleasurable and the smoker is given reinforcement each time he or she has a cigarette. Nicotine is a stimulant and it has powerful actions on the brain’s mesolimbic dopamine center, otherwise known as the rewards or pleasure center, and inhaled nicotine produces a mild level of euphoria, it decreases fatigue, increases alertness, and it also can be very relaxing. An excess of nicotine and/or small amounts delivered to a child or a nicotine-naïve adult can be very toxic. A dose of 2-5 mg may produce signs and symptoms in a nicotine-naïve adult11 and a large amount of nicotine can cause death. Nicotine is a stimulant and most cases of nicotine poisoning reflect that but severe cases can cause depressant effects. Some of the common signs and symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning are listed in Table 3. Table 3: Signs And Symptoms Of Acute Nicotine Poisoning Agitation Bradycardia ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 5 Cholinergic syndrome Coma Diaphoresis Diarrhea Drowsiness Hyperpnea Hypertension Nausea Pallor Respiratory depression Seizures Tachycardia Vomiting Nicotine can also affect the metabolism of drugs. Some of the components of cigarette smoke have been proven to increase the activity of certain cytochrome p450 enzymes. This enzyme induction can significantly increase the metabolism of commonly used drugs such as β-adrenergic antagonists, benzodiazepines, and cyclic antidepressants, and some who smoke and are taking one of these medications may be receiving a sub-therapeutic dose.11,12 Pathophysiology Of Acute Nicotine Addiction Nicotine is addictive. After years of study the Surgeon General declared in 1988 that “ . . . cigarettes are addicting, similar to heroin and cocaine, and nicotine is the primary agent of addiction.”1,13 Nicotine addiction is very complex and a detailed discussion of the subject is beyond the scope of this module and this author’s ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 6 knowledge base. However, several basic points about the process are useful for an understanding of tobacco use disorder.1,14-16 Tobacco Use Disorder and Addiction Tobacco use disorder is a substance use disorder and a crucial aspect of substance use disorders is “ . . . an underlying change in brain circuits that may persist beyond detoxification, particularly in individuals with severe disorders. The behavioral effects of these brain changes may be exhibited in the repeated relapses and intense drug craving when the individuals are exposed to drug-related stimuli.”17 In basic terms, smoking produces structural changes in the brain that make it very difficult to quit the habit. Chronic nicotine use produces drug-taking behavior and tolerance and smoking cessation can cause a withdrawal syndrome. Notably, nicotine addiction is the result of neurological and biological adaptations to the chronic administration of nicotine and a change in the number of nicotinic receptors. The dopaminergic system is the main part of the central nervous system (CNS) that is involved in drug addiction and over time and as someone is continually exposed to nicotine, the CNS becomes adapted to and seeks out the high levels of dopamine that are produced by nicotine. The physical and psychoactive effects of nicotine are primarily mediated through dopamine release in the reward center of the brain, and the release of dopamine produces the immediate pleasurable sensations and it acts to reinforce the act of smoking. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 7 Nicotine binding to the nicotinic receptors also stimulates the release of GABA, glutamate, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters. The firstline smoking cessation medications work by their action on the nicotinic receptors, but because other neurotransmitters are influenced by nicotine, alternative medications may be needed for successful smoking cessation. The daily nicotine intake and the blood nicotine level of a smoker depends on: 1) how many cigarettes are smoked; 2) how the cigarette is smoked (inhalation depth and pattern, etc.); and, 3) the smoker’s rate of metabolizing nicotine. Some metabolize nicotine faster than others do and this is an inducement to smoke more cigarettes to obtain the pleasure of smoking and to avoid cravings. The Definition And Diagnosis Of Tobacco Use Disorder Tobacco use disorder is considered to be a substance use disorder (SUD). The DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders are listed in Table 4. Table 4: DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Use Disorders Continued use despite negative interpersonal consequences Craving or urge to use the substance Failure to fulfill obligations Persistent desire to cut down or quit Reduced social or recreational activities Significant time spent taking or obtaining substance Tolerance (excludes prescription medication) Use in physically hazardous situations ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 8 Use despite knowledge of harms Using larger amounts than intended Withdrawal (excludes prescription medication) 0–1 criteria 5 no SUD 2–3 criteria 5 mild SUD 4–5 criteria 5 moderate SUD >5 criteria 5 severe SUD These criteria provide a basic picture of a substance use disorder. The DSM-5 definition of tobacco use disorder and the diagnostic criteria for it are listed in Table 5. It should be noted that these have been changed slightly from the original version but nothing substantive has been omitted. Table 5: DSM-5 Definition of Tobacco Use Disorder A problematic pattern of tobacco use that causes clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period: 1. Tobacco is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than the user intended. 2. The user has a persistent desire to cut down or control his or her tobacco use or he or she makes persistent, unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control tobacco use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities that are needed to obtain or use tobacco. 4. The user has a craving, a strong desire, or a strong urge to use tobacco. 5. Recurrent tobacco use that is a direct cause of failure to fulfill ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 9 major role obligations at work, school, or home (i.e., interference with work). 6. Continued tobacco use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of tobacco (i.e., arguments with others about tobacco use). 7. The user gives up or reduces important social, occupational, or recreational activities because of tobacco use. 8. Recurrent tobacco use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (i.e., smoking in bed). 9. Tobacco use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by tobacco. 10. Tolerance, which is defines as either; a) A need for a markedly larger amount of tobacco to achieve the desired effect; or, b) A markedly diminished effect from the same amount of tobacco. 11. Withdrawal, which is evidenced by either: a) Characteristic criteria for tobacco withdrawal syndrome; or, b) the use of tobacco or a nicotine-containing product to alleviate signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. The clinician should also determine if the patient is in early remission or sustained remission and if the patient is on maintenance therapy, and in a controlled environment. Early Remission The patient had met the full criteria for tobacco use disorder; none of these have been present for at least three months but for less than 12 months; and, criteria number 4 may be present. Sustained Remission ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 10 The patient had met the full criteria for tobacco use disorder; none of these have been present for at least 12 months; and, criteria number 4 may be present. Maintenance Therapy The patient is taking a long-term maintenance medication. In a controlled environment the patient is in an environment where access to tobacco is restricted. A mild tobacco use disorder is diagnosed if the patient has two to three symptoms. Moderate tobacco use disorder is diagnosed if the patient has four to five symptoms, and a severe tobacco use disorder is diagnosed if the patient has six or more symptoms. People who have anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, psychosis, or another substance use disorder are at risk for developing tobacco use disorder.5,18,19 There is evidence of an inherited trait that can predispose someone to the development of tobacco use disorder and certain cultural and ethnic factors may put a person at risk, as well.5,20 Tobacco use disorder is common in people who use cigarettes or smokeless tobacco but not prescription nicotine products.5 Many tobacco users report a craving for tobacco if they have not used it for several hours, and cessation of tobacco can cause a well-described withdrawal syndrome.5 Electronic cigarettes, often known as ecigarettes are quite popular and also controversial. They do not deliver as much nicotine as a cigarette, but it is not clear if the use of ecigarettes discourages or encourages the use of other nicotinecontaining products.21,22 Tobacco Withdrawal ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 11 This learning module will not discuss tobacco withdrawal at length, but it is useful for the reader to know the diagnostic criteria for this substance use disorder. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for tobacco withdrawal are listed in Table 6.23 Table 6: DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Tobacco Withdrawal Daily use of tobacco for at least several weeks. Abrupt cessation of tobacco use a reduction in the amount of tobacco used, followed within 24 hours by four or more of these signs or symptoms Irritability, frustration, or anger Anxiety Difficulty concentrating Increased appetite Restlessness Depressed mood Insomnia In the DSM-5 criterion, the signs or symptoms identified cause clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning in individuals affected by a tobacco use disorder. Additionally, the signs or symptoms are not attributed to another medical condition and are not better explained by another mental disorder, including intoxication or withdrawal from another substance Smoking Cessation: Basic Principles Because smoking and the use of nicotine-containing products are still so common, asking patients if they smoke or use nicotine-containing ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 12 products should be standard protocol. The U.S. Preventive Service Task Force recommends that clinicians ask all patients who are ≥ 18 years of age about tobacco use, and tobacco cessation interventions should be provided for patients who use tobacco.24 The benefits of smoking cessation are clear and unequivocal.25 Someone who quits smoking will live longer and is much less likely to develop cancer, coronary heart disease, or lung disese,25 and these benefits extend even to people who have been smoking for decades and then quit. Of significance, a reduced risk of mortality has been reported for people who are > age 80 and have stopped smoking.26 Nicotine is a powerful psychoactive drug, however, and smoking cessation does have risks.25 It should be noted that these risks are directly related to smoking cessation, which is further highlighted in the section below. Risks of Smoking Cessation Risks associated with therapies that are used as aids to smoking cessation are discussed in this section. Cough and Mouth Ulcers Patients who stop smoking may notice that for several months they are coughing more frequently than they did prior to quitting and they may develop mouth ulcers, as well.25 Coughing and mouth ulcers should resolve within several weeks. Mental Illness ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 13 Depression A depressed mood is one of the diagnostic criteria of tobacco withdrawal, and people who have a history of psychiatric illness are more likely to develop depression during smoking cessation.25 But in this patient population the benefits of smoking cessation appear to outweigh the risks,25 and a recently published study found that most people who stop smoking are not at risk for developing depressive symptoms.27 Psychotrophic Medication The rates of tobacco use among people with mental illness have been reported to be high. Pharmacotherapy and counseling can help those with mental illness to quit smoking. However, when individuals in a smoking cessation program have relapsed, medical providers treating individuals continuing to use tobacco should follow them more consistently to evaluate the effect of smoking on medication efficacy to treat psychiatric symptoms. Patients should be educated on the impact of tobacco use on psychotropic medication efficacy and cost, as well as the importance of informing their medical provider of any amount of tobacco use while on psychotropic medication. Weight Gain Weight gain after smoking cessation is common, probably caused by increased food intake, decreased metabolic rate and other physiological changes.25 The average weight gain is 4-5 kg but much higher weight gains are possible and there is a wide variability in how much weight will be gained.28 The choice of medication that is used as ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 14 an aid to smoking cessation does not appear to influence weight gain.29 Cardiovascular Disease Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is common among smokers and the three drugs used as aids to smoking cessation, nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, have the potential to cause cardiovascular events such as arrhythmias and non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI). However, in 2015 Sharma, et al., examined the available evidence and concluded that pharmacotherapy as an aid to smoking cessation does not increase the risk for cardiovascular events in patients with or without pre-existing cardiovascular disease.30 The authors did caution that “ . . . there have been no large RCTs (randomized controlled trials) in patients in the first few weeks post acute coronary syndrome.24 Therefore, Clinical Practice Guidelines recommends using nicotine replacement therapy with caution in patients with CVD — especially within 2 weeks post MI, especially if they have serious arrhythmias or progressive angina.”12 Beginning The Process Of Smoking Cessation Using a process called the five A’s has been advocated as an effective way of helping people to stop smoking. The five A’s include the following steps: Ask, Advise, Asses, Assist, and Arrange.31,32 Ask The first step is to find out how much tobacco and nicotine-containing products the patient uses, i.e., what is used, how much, how often, and the duration of use. It’s important to be specific. It has been shown that people who are intermittent smokers may not consider ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 15 themselves to be smokers or not consider alternative types of nicotine delivery devices to be dangerous.31 In addition, some patients may not consider smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes and other nicotine delivery devices to be part of their nicotine habit so its important to be sure to ask about these. The interviewing clinician should also determine the patient’s level of substance use as the higher the level of use the more difficult it will be to quit. Does he/she begin the day with a cigarette? Has the patient been smoking since early adolescence? Do they smoke a lot? Has the patient tried to quit before? It should be noted that the term pack years is often used to describe someone’s smoking history rather than simply determining how many cigarettes are smoked each day. Pack years is calculated by: 1) Multiplying the number of packs smoked each day by years as a smoker; or, 2) dividing the number of cigarettes smoked each day by 20 (the amount in a pack) and multiplying this number by the number of years someone has been smoking. For example, 20 cigarettes a day for 25 years = 25 pack years. As the duration and intensity of tobacco use directly affects health, pack years is used to approximate the risk a smoker has of developing tobacco-related diseases. Advise After determining the patient’s pattern of use and level of use the patient should be advised to quit smoking. This may seem simplistic, especially given the difficulty of stopping smoking. But there is evidence that even simple advice from a caregiver can influence some patients to quit smoking and, although the reported effect may be ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 16 small (1%-2%), if advice to quit was given to every smoker the overall public heath benefit would be quite large.32 Advice should be clear and unequivocal and should be accompanied by offers of help. Assess Smokers will differ in their readiness to quit. Some will be eager to stop smoking and others may be ambivalent. Assist Provide the patient with practical assistance that he/she will need for smoking cessation, such as formulating a plan, prescribing medications, and/or a referral to counseling. Arrange Arrange for follow-ups to evaluate progress. Once the decision has been made to quit, it is advisable for the patient to set a quit date and several recent (2014, 2016) studies have shown that abrupt quitting produced a higher rate of abstinence than a gradual reduction of tobacco use.33,34 The harm from smoking is directly proportional to how many cigarettes are used. However, as with second-hand smoke there is no safe and harmless number of cigarettes, and simply reducing the number of cigarettes that are smoked each day will not provide lasting heath benefits.25,31,35 Quitting is the only answer. Aids To Smoking Cessation ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 17 Smoking cessation programs use behavioral interventions, medications, or both. A program that combines both has been shown to be the most effective.31,33,36 Behavioral Interventions There are many behavioral-based interventions that can be helpful as aids to smoking cessation. Direct provider to patient interaction, group therapy, specialized clinics, self-help intervention using educational resources like printed material or videos, web-based and text-based resources, and telephone applications and telephone contact counseling have all been successfully used.33,37 The specific intervention chosen will depend on availability, cost, and patient preference. Important aspects of behavioral interventions as aids to smoking cessation that can increase the chance of success include the following.37-40 Duration There appears to be a direct relationship between the duration of the intervention sessions and success at attaining abstinence. Longer intervention sessions results in greater success.37,38 Completeness The patient should be given as much information about quitting smoking as he/she can comprehend and use. Form ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 18 Many behavioral interventions for smoking cessation are based on a cognitive behavioral therapy model. With this approach patients learn practical skills such as identifying triggers for smoking, distraction techniques, and problem solving. For example, the smoker may identify large social gatherings as a trigger that stimulates the desire to smoke. In those situations the smoker can use distraction techniques such as chewing gum or mentally reviewing the benefits of smoking cessation. The Five Rs The U.S. Preventive Task Force identified five variables of behavioral interventions that may help patients to stop smoking. These variables are called the the Five R’s. Relevant to the patient. The patient should be educated about the Risks of smoking that apply to him or her. The Rewards of smoking cessation should be outlined. Roadblocks that may interfere with smoking cessation should be identified. Repetition is important – it takes time and repetition for smoking cessation information to be absorbed and used. Pharmacotherapy And Smoking Cessation Pharmacotherapy (with or without behavioral interventions) can significantly influence smoking cessation rates in adults.37,41 There are three drugs that are approved by the Food and Administration (FDA) for assisting patients with smoking cessation: bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and varenicline. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 19 Bupropion Bupropion is a commonly prescribed anti-depressant, and the sustained-release form has FDA approval as an aid to smoking cessation treatment. It inhibits the re-uptake of dopamine and norepinephrine and it also acts as a competitive inhibitor at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Bupropion also decreases cravings for nicotine and prevents withdrawal signs and symptoms, and it has been shown to be very effective at maintaining abstinence when it is used as a monotherapy.42,43 When used for smoking cessation bupropion SR (sustained release) is given 150 mg once a day for three days. The dose is then increased to 150 mg twice a day and the course of treatment is 7 to 12 weeks. If needed, a longer duration of therapy can be used and for some patients this may be necessary.42 Therapy with bupropion SR should begin at least one week prior to the day the patient stops smoking; this is needed because it takes five to seven days for a steady-state blood level to be attained. The most common adverse effects of bupropion SR are agitation, dry mouth, headache, insomnia, and nausea.42 Bupropion reduces the seizure threshold and during clinical trials of bupropion as an aid to smoking cessation seizures have occurred but the risk for this is very, very low.44,45 Using bupropion is contraindicated if a patient has a seizure disorder or a predisposition to seizures. A U.S. Boxed Warning has been issued on bupropion that alerts prescribers that antidepressants can increase the risk of suicidal ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 20 behavior and thoughts in children, adolescents, and young adults. A recent (2016) review did not find that bupropion increased the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse effects,46 but it does seem prudent to follow the advice of the U.S. Boxed Warning to “ . . . monitor patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy and closely observe them for clinical worsening, including the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the health care provider.”47 Nicotine Replacement Therapy Nicotine replacement therapy delivers nicotine without exposure to the harmful compounds of burning tobacco. Nicotine-containing gum, inhalers, lozenges, patches, or sprays have been proven to be effective at reducing craving, preventing withdrawal, and inducing sustained abstinence from tobacco.41,42, 44 Compared to placebo, NRT can double the success rate of smoking cessation efforts.48 NRT is typically used for two to three months after someone has stopped smoking.42 These products deliver a much lower dose of nicotine than a cigarette and a nicotine use disorder and addiction from their use very rarely occurs.42 The optimal mode of use of NRT is combination therapy; the patches are used for a long-acting effect and are supplemented by the gum, lozenges, inhaler, or spray.42 The gum, lozenges, and patches can be purchased over-the-counter; the inhaler and the sprays are available by prescription. There is little data comparing the effectiveness of these products. Patient preference and cost are the deciding factors as to which one is used. The dose of the replacement product will depend on the number of cigarettes the patient had been smoking each day. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 21 The duration of therapy is usually for two to three months after the patient has stopped smoking but this can be adjusted as needed. Details about nicotine gum, inhalers lozenges, patches, and sprays are provided below.49 Nicotine Gum Nicotine gum is provided as 2 mg or 4 mg, and the peak nicotine level is attained in 20 minutes. Patients should be instructed to chew one piece every 1 to 2 hours as needed for six weeks and then gradually decrease the intake for the next 12 weeks. The gum should be chewed until the nicotine flavor is noticed and then the gum should be placed next to the buccal mucosa until the taste disappears. The gum should be chewed and placed next to buccal mucosa again, and this cycle repeated for 30 minutes and before the gum is finally discarded. The gum should not be chewed very rapidly as this causes the nicotine to be released from the gum at a rate that is too fast for it to be absorbed. Coffee, tea, or carbonated beverages should not be consumed while chewing nicotine gum. Such products are acidic and concurrent use with nicotine gum decreases the absorption of nicotine. Nicotine gum can cause mild and temporary gastric distress. Nicotine Inhaler Nicotine inhalers consist of a mouthpiece and a cartridge that has 10 mg of nicotine. The inhalers deliver 4 mg of nicotine via an inhalation. The nicotine-containing vapor is absorbed through the mucosa of the oropharynx; only a very small percentage reaches the lungs and all of ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 22 the nicotine should be gone after 20 minutes of inhaling. The dose should be individualized for each patient but a typical starting dose is 6-12 cartridges each day for 6-12 weeks. After the initial 12 weeks the number of cartridges used each day can be decreased over the following 6-12 weeks and then therapy can be stopped. These products are considered particularly useful because their use mimics the behavioral and tactile sensations of smoking a cigarette. Irritation of the mouth and throat are common during the first few weeks of therapy. Nicotine Lozenge Nicotine lozenges have 2 mg or 4 mg of nicotine. The lozenge should be allowed to dissolve over 30 minutes, and the patient should use one lozenge every one to two hours. After six weeks of use, the number used should slowly be decreased and use stopped after 12 weeks. Local irritation is a common side effect. Nicotine Patches Nicotine patches deliver a continuous, low dose of nicotine over 24 hours. Because of the transdermal delivery of nicotine, nicotine levels in the plasma rise very slowly, which is helpful for preventing withdrawal but can leave patients vulnerable to cravings. The patches contain 7 mg, 14 mg, or 21 mg of nicotine, and the patch is applied and left on for 24 hours. An example of a standard approach is to use a 21 mg patch for six weeks and then a 14 mg patch for two weeks. Insomnia and vivid dreaming are often experienced if the patient leaves the patch on overnight. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 23 Nicotine Spray Nicotine sprays may contain 10 mg per mL of nicotine, and each spray delivers 0.5 mg of nicotine. These products deliver nicotine to the nasal mucosa so the nicotine plasma level increases much faster than it does with gum, lozenges, or inhalers. Patients should use one to two sprays an hour, one spray into each nostril, and the maximum number of sprays should not exceed 80 per day (40 for each nostril). Nasal irritation is very common and it may persist well into the therapy. Varenicline Varenicline acts as a partial agonist at the α4-β2 subunit of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Varenicline binds to these receptors and by doing so it: 1) Stimulates the release of dopamine, thus reducing the signs and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal caused by the absence of nicotine; and, 2) Prevents the binding of nicotine to the acetylcholine receptors, preventing some of the pleasurable effects of nicotine.41 Controlled studies have proven the effectiveness of varenicline for smoking cessation;42,44,50,51 and, there is evidence that suggests it is the most effective monotherapy for smoking cessation.50 The initial dose of varenicline is 0.5 mg/day for three days. This is followed by 0.5 mg twice/day for four days, then 1 mg twice/day for the rest of a 12 week course.52 Smokers should stop smoking seven days after beginning therapy with the drug. The most common adverse effect caused by varenicline is nausea.50 Approximately one-third of patients who take varenicline will become ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 24 nauseous50 but only a small number will discontinue therapy for this reason.50 In most cases the nausea is mild to moderate in severity and subsides over time.50 Varenicline has been associated with an increased risk for adverse neuropsychiatric events.50 The true risk for serious neuropsychiatric events is not known, and several recent (2013, 2015) analyses of data did not find evidence that the use of varenicline increased the risk of attempted suicide, death, depression, suicidal ideation, or other adverse neuropsychiatric events.53,54 However, the prescribing information for varenicline contains a U.S. Boxed Warning (commonly called a black box warning); “Serious neuropsychiatric events including but not limited to, depression, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide have been reported in patients taking varenicline. Some reported cases may have been complicated by the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal in patients who stopped smoking. Depressed mood may be a symptom of nicotine withdrawal. Depression, rarely including suicidal ideation, has been reported in smokers undergoing a smoking cessation attempt without medication. “52 There was also a concern for several years that the use of varenicline increased the risk of developing serious and non-serious cardiac events,30 but current evidence and data analysis have shown that any increase in cardiac events caused by varenicline are insignificant, and an FDA safety communication indicated that “ . . . the events were uncommon in both the treatment and placebo group and the increased risk observed was not statistically significant . . . (and) there is no evidence from the trials so far that varenicline is linked to increased heart and circulatory problems.”55 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 25 Alternative Therapies For Smoking Cessation Alternative approaches to support patients during their course of care in a smoking cessation program have been reported to provide value and good results of quitting smoking. This section reviews several alternative approaches and benefits of acupuncture, hypnosis and ecigarettes. Acupuncture Acupuncture may help smokers to quit56 but a 2014 analysis of its effectiveness as an aid to smoking cessation concluded that “ . . . lack of evidence and methodological problems mean that no firm conclusions can be drawn.”57 Hypnosis As with acupuncture, the evidence is equivocal for the effectiveness of hypnosis as an aid to smoking cessation and more research would be needed to determine how well and for whom it can work.31 E-cigarettes A popular alternative to traditional cigarettes is the e-cigarette, as the e-cigarettes do not deliver the same amount of tar and carcinogenic products of combustion as traditional cigarettes. However, there is no government control of e-cigarettes, and there exists a lack of data on their health effects.58 According to the American Heart Association: “ . ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 26 . . in general, the health effects of e-cigarettes have not been well studied, and the potential harm incurred by long-term use of these devices remains completely unknown.”59 There is currently conclusive evidence that e-cigarettes are an effective aid to smoking cessation.60 Smoking Cessation: Failure And Success Each year approximately two out of every three smokers will try and quit but the majority will be unsuccessful.61,62 Even when using what is considered to be optimal treatment, only 30% or so of smokers will still be abstinent after one year.31 There are many reasons why smokers find it difficult to quit and difficult to maintain abstinence, including but not limited to: side effects of cessation such as cravings and withdrawal, weight gain, mood changes, poor social support, access problems for smoking cessation programs, poor preparation for quitting, and incorrect use of medications.31 These issues, along with the addictive properties of nicotine, clearly present smokers with a considerable challenge when they try to quit and to cease the smoking habit long-term. If a patient is experiencing difficulty with his/her smoking cessation program, he or she can be helped to quit and relapse can be prevented. The use of the following techniques can prevent and treat relapses.31 Many patients who try and quit do so independently and have not used medications or sought professional help. If a patient states that he or she has tried to stop smoking be sure to find out what efforts were made. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 27 To prevent a relapse be sure to maintain close and consistent contact with the patient to provide encouragement, support, and ongoing education and to identify problems as they arise. To treat a relapse it must be identified how and why the relapse happened. When the problem(s) have been identified, the patient should be offered practical solutions and most certainly closely followed on his/her progress. If weight gain is a problem, exercise and a nutritionist consultation can be recommended. Ongoing education on the proper use of medications or the addition of a second medication may be needed. The provider should explore whether the patient clearly learned what situations and triggers might cause a relapse. It can be helpful during follow-up visits to review these with a patient. Continuous follow up is essential. Patients who are trying to quit smoking and those who have quit need support and follow-up. This is a key factor for success and, because a relapse can happen even years after quitting, some patients may need periodic “check-ups” to help them maintain abstinence. Patient Resources There are many free and easily accessible resources that can help someone who is contemplating smoking cessation or who wants to stop. The ones listed below represent only a small number of what is available. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 28 Freedom from Smoking® is a program offered by the American Lung Association. Use this link: http://www.lung.org/stopsmoking/i-wantto-quit/how-to-quit-smoking.htmlv and scroll down the page to the section title Get Help. The American Lung Association also has a help line, 1- 800 LUNG USA. Smokefree.gov is a website of the United States Department of Health and Human Services. It includes information on healthy habits, how smoking affects one's health, and tips on preparing to quit. It also includes resources specifically for women, teens, and Spanish-speaking patients. 1-800-QUIT Now (1-800-784-0669) is a toll free number that connects smokers to the Quit For Life® program, sponsored by the American Cancer Society. Summary Tobacco use poses enormous public health problems and is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States. Although the number of Americans who smoke has decreased, tobacco and cigarette smoking are still the primary causes of or contributors to certain cancers, heart disease, common respiratory diseases and other acute and chronic pathology. Tobacco use disorder is considered to be a substance use disorder (SUD) according to DSM-5 criteria that occur over a 12-month period. Risks associated with therapies that are used as aids to smoking cessation are multifarious and should be closely monitored. Clinicians ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 29 should follow patients closely during remission to determine early or sustained remission, as well as maintenance therapy and whether the patient is in a controlled environment. There are three drugs that are approved by the Food and Administration (FDA) for assisting patients with smoking cessation, which are bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and varenicline. Alternative approaches to support patients during their course of care in a smoking cessation program, such as acupuncture, hypnosis and e-cigarettes, have been reported to provide value and good results of quitting smoking. To treat relapse it is important for the patient’s provider to identify how and why the relapse occurred. When the problem(s) have been identified, the patient should be offered practical solutions and his or her progress closely followed. Patients’ experiencing difficulty with smoking cessation can be helped to quit, and relapse prevented, by treating patients in a smoking cessation program according to recommended techniques and free, easily accessible resources are available to those desiring to stop smoking. Importantly, there is evidence that even simple advice from a caregiver can influence some patients to quit smoking and, although the reported effect may be small, if advise to quit was given to every smoker the overall public heath benefit would be quite large. Smoking cessation advice should be clear and accompanied by offers of help by health care providers. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 30 References 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Printed with corrections, January 2014. 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(44):1233–1240. 3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association. Substance Use Disorders. October 27, 2015. Retrieved online at http://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/substance-use. Accessed June 19, 2016. 4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Retrieved online at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-ofprogress/exec-summary.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2016. 5. American Psychiatric Association. Tobacco use disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. Alexandria, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Second-Hand Smoke (SHS) Facts. August 20, 2015. Retrieved online at ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 31 http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/secondh and_smoke/general_facts/index.htm. Accessed June 19, 2016. 7. Hajizadeh M, Nandi A. The socioeconomic gradient of secondhand smoke exposure in children: evidence from 26 low-income and middle-income countries. Tob Control. 2016 Jun 16. pii: tobaccocontrol-2015-052828. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015052828. [Epub ahead of print] 8. Fischer F, Kraemer A. Meta-analysis of the association between second-hand smoke exposure and ischaemic heart diseases, COPD and stroke. BMC Public Health. 2015 Dec 1;15:1202. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2489-4. 9. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Forno E, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Celedón JC. Risk and protective factors for childhood asthma: What is the evidence? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016 Jun 8. pii: S22132198(16)30139-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.05.003. [Epub ahead of print] 10. Russo ET, Hulse TE, Adamkiewicz G, et al. Comparison of indoor air quality in smoke-permitted and smoke-free multiunit housing: findings from the Boston Housing Authority. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(3):316-322. 11. Benowitz NA. Nicotine. In: Poisoning & Drug Overdose. Fifth ed, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. 12. Li H, Shi Q. Drugs and diseases interacting with cigarette smoking in US prescription drug labeling. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54(5):493-501. 13. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 32 Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1988. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 88-8406. 14. Pérez-Rubio G, Sansores R, Ramírez-Venegas A, Camarena Á, Pérez-Rodríguez ME, Falfán-Valencia R. Nicotine addiction development: From epidemiology to genetic factors. Rev Invest Clin. 2015;67(6):333-343. 15. Falcone M, Lee B, Lerman C, Blendy JA. Translational research on nicotine dependence. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016 Feb 13. [Epub ahead of print] 16. D'Souza MS. Neuroscience of nicotine for addiction medicine: novel targets for smoking cessation medications. Prog Brain Res. 2016;223:191-214. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.07.008. Epub 2015 Nov 23. 17. American Psychiatric Association. Substance use disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. Alexandria, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 18. Young-Wolff KC, Kline-Simon AH, Das S, Mordecai DJ, MillerRosales C, Weisner C. Smoking trends among adults with behavioral health conditions in integrated health care: A retrospective cohort study. Psychiatr Serv. 2016 Apr 15:appips201500337. [Epub ahead of print] 19. Das S, Tonelli M, Ziedonis D. Update on smoking cessation: Ecigarettes, emerging tobacco products trends, and new technology-based interventions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016 May;18(5):51. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0681-6. 20. Ross KC, Gubner NR, Tyndale RF, et al. Racial differences in the relationship between rate of nicotine metabolism and nicotine intake from cigarette smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2016 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 33 May 11;148:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.05.002. [Epub ahead of print] 21. Schraufnagel DE, Blasi F, Drummond MB, et al. Electronic cigarettes. A position statement of the forum of international respiratory societies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(6):611-618. 22. Brandon TH, Goniewicz ML, Hanna NH, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: a policy statement from the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):952-963. 23. American Psychiatric Association. Tobacco withdrawal. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. Alexandria, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 24. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Tobacco use in adults. In: The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved online at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/. Accessed June 27, 2016. 25. Rigotti NA. Benefits and risks of smoking cessation. UpToDate. March 4, 2015. Retrieved online at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/benefits-and-risks-ofsmoking-cessation. Accessed June 21, 2016. 26. Gellert C, Schöttker B, Brenner H. Smoking and all cause mortality in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11): 837-844. 27. Cooper J, Borland R, Yong HH, Fotuhi O, et al. The impact of quitting smoking on depressive symptoms: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey. Addiction. 2016 Feb 25. doi: 10.1111/add.13367. [Epub ahead of print ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 34 28. Krukowski RA, Bursac Z, Little MA, Klesges RC. The relationship between body mass index and post-cessation weight gain in the year after quitting smoking: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 15;11(3):e0151290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151290. eCollection 2016. 29. Yang M, Chen H, Johnson ML, et al. Comparative effectiveness of smoking cessation medications to attenuate weight gain following cessation. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51(5):586-597. 30. Sharma A, Thakar S, Lavie CJ, et al. Cardiovascular adverse events associated with smoking-cessation pharmacotherapies. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015 Jan;17(1):554. doi: 10.1007/s11886014-0554-8. 31. Rigotti NA. Overview of smoking cessation in adults. UpToDate. April 27, 2016. Retrieved online at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-smokingcessation-management-in-adults. Accessed June 21, 2016. 32. Park, ER. Behavioral approaches to smoking cessation. UpToDate. April 25, 2016. Retrieved online at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/behavioral-approaches-tosmoking-cessation/contributors. Accessed June 27, 2016. 33. Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado G, et al. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 May 31;(5):CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4. 34. Baha M, Le Faou AL. Gradual versus abrupt quitting among French treatment-seeking smokers. Prev Med. 2014;63:96-102. 35. Lindson-Hawley N, Banting M, West R, Michie S, Shinkins B, Aveyard P. Gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation: A randomized, controlled non-inferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(9):585-592. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 35 36. Begh R, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Does reduced smoking if you can't stop make any difference? BMC Med. 2015 Oct 12;13:257. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0505-2. 37. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 24;3:CD008286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub3. 38. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622-634. 39. Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Prospective cohort study of the effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments used in the "real world". Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(10):1360-1367. 40. Park CB, Choi JS, Park SM, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of virtual cue exposure therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for nicotine dependence. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(4):262-267. 41. Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158-176. 42. Rigotti NA. Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in adults. UpToDate. May 31, 2016. Retrieved online at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-forsmoking-cessation-in-adults. Accessed June 23, 2016. ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 36 43. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jan 8;(1):CD000031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub4. Review. 44. Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 May 31;(5):CD009329. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. 45. Little MA, Ebbert JO. The safety of treatments for tobacco use disorder. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(3):333-341. 46. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL,West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016 Apr 22. pii: S0140-6736(16)30272-0. doi: 10.1016/S01406736(16)30272-0. [Epub ahead of print] 47. Lexicomp.® Bupropion (Lexi-Drugs). June 16, 2016. Retrieved online at http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/6485 #black-box-warn. Accessed June 25, 2016. 48. Klein JW. Pharmacotherapy for substance use disorders. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(4):891-910. 49. LexiComp.® Nicotine (Lexi-Drugs) June 3, 2016. Retrieved online at http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/7365. Accessed June 25, 2016. 50. Burke MV, Hays JT, Ebbert JO. Varenicline for smoking cessation: a narrative review of efficacy, adverse effects, use in at-risk ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 37 populations, and adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:435-441. 51. Cahill K, Lindson-Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 9;(5):CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub7. 52. LexiComp.® Varenicline (Lexi-Drugs). June 3, 2106. Retrieved online at http://online.lexi.com.online.uchc.edu/lco/action/doc/retrieve/doci d/patch_f/512661. Accessed June 25, 2016. 53. Gibbons RD, Mann JJ. Varenicline, smoking cessation, and neuropsychiatric adverse events. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1460-1467. 54. Thomas KH, Martin RM, Knipe DW, Higgins JP, Gunnell D. Risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with varenicline: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015 Mar 12;350:h1109. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1109. 55. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: safety review update of Chantix (Varenicline) and risk of cardiovascular adverse events. Retrieved online at http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm330367.htm. Accessed June 25, 2016. 56. Di YM, May BC, Zhang AL, Zhou IW, Worsnop C, Xue CC. A metaanalysis of ear-acupuncture, ear-acupressure and auriculotherapy for cigarette smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:14-23. 57. White AR, Rampes H, Liu JP, Stead LF, Campbell J. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 38 Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jan 23;(1):CD000009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000009.pub4. 58. Bhatnagar A, Whitsel LP, Ribisl KM, et al. Electronic cigarettes: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(16):1418-1436. 59. McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD010216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2. 60. Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 Apr 25. pii: ntw119. [Epub ahead of print] 61. Lavinghouze SR, Malarcher A, Jama A, Neff L, Debrot K, Whalen L. Trends in quit attempts among adult cigarette smokers - United States, 2001-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(40):1129-1135. 62. Falcone M, Lee B, Lerman C, Blendy JA. Translational research on nicotine dependence. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016 Feb 13. [Epub ahead of print] ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 39