* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Approved

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Approved

on the conference of the Department

of Obstetrics and Gynecology with the Course

of Infant and Adolescent Gynecology

“____” _____________200 p.

protocol No

T.a.The Head of the department, Professor

O.A.Andriiets’___________

Methodological instruction

on the themes singled out for independent study

“General symptomatology of gynecologic diseases”

Subject-gynecology

For 5 year students of medical

faculty

2 academic hours

Developed by assistant, PhD

Oksana Bakun

Chernivtsi, 2008

I. Scientific and methodical grounds of the theme

Examination of gynecological patient consists of history taking, objective

(general and special) and additional methods of examination. The examination

begins with obtaining the history in accordance with a certain plan. First of all, the

passport data is required: surname, name, patronymic ,and also birth date

(woman’s age). This is done because each phenomenon in different age of women

lifecycle can have different meaning, for example, absence of menses in young

women and women in menopause.

II. Aim:

A student must know:

1. Abdominal examination.

2. Vaginal examination.

3. Rectal examination.

4. Cervical smears for exfoliative cytology.

5. Further gynecological investigations.

A student should be able:

1. To carry out an objective gynecologic examination of a patient.

1. To make up a plan of a patient’s examination.

III. Recommendations to the student

THE PHYSICIAN-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

Patient Motivation and Comfort

Because people seek medical care for several reasons, it is important for the

physician to understand why the patient is in his or her office A failure to do so

may lead to dissatisfaction on the part of the patient For example, a patient may

come to the gynecologist's office with a stated complaint of pelvic pain and an

unstated fear that the pain is being caused by a sexually transmitted disease If the

physician focuses on evaluating the pain and provides effective analgesia but does

not uncover the underlying problem, the patient may leave the office pain-free but

dissatisfied. Therefore, the physician should make several attempts during the

course of the history and examination to determine why the patient made the

appointment and what issues the patient needs to have addressed during the office

visit In addition to understanding and meeting the pa tient's needs, the physician

must be prepared to provide a medical evaluation in a physically and emotionally

comfortable setting. A woman's initial visit to the gynecologist's office can be

fraught with anxiety, concern, and even humiliation. Whatever her age, social

background, or previous experience (all of these influence her reaction), she often

expects the encounter with the gynecologist and the examination to be

uncomfortable both emotionally and physically. Unfortunately rumor and previous

experiences may have given this anxiety a very real foundation. It is the physician's

responsibility to allay undue apprehension, dispel false impressions, and make the

visit as comfortable and informative as possible so that the patient leaves the office

calm and in an improved frame of mind. This is best achieved by an understanding

attitude and a matter-of-fact approach. Condescension and domination have no

place in the physician-patient relationship.

Even under the best of circumstances the patient is likely to find the visit

disagreeable. Soon after entering the office or clinic she is asked to discuss her

most personal problems, which she has mentioned to few, if any, others. Then,

after verbally exposing herself, she must undress, put on the most unappealing of

garments, and be examined by a stranger. No wonder the visit to the gynecologist

for an annual check up or for help with a pressing problem is seldom anticipated

with enthusiasm. Indeed, subsequent visits are usually as trying as the first.

The patient is sensitive to subtle nuances in the physician's words or facial

expression, a fact seldom appreciated by the busy practitioner. The physician's

demeanor is extremely important in allaying the patient's anxiety and establishing

rapport; the physician who appears abrupt, preoccupied, hurried, hesitant,

embarrassed, or flippant can destroy the possibility of a satisfactory physicianpatient relationship. Frivolity and lightheartedness rarely have a place in the initial

evaluation. The seriousness of the moment for the patient should be foremost in the

physician's mind. Propriety of address and composure are qualities that all patients

appreciate and respect. The physician should express sincere concern in a friendly,

direct atmosphere.

There are other rules for the relationship of an obstetrician-gynecologist with

the patient. Unless the patient gives permission to call her by her first name, the

physician should address her by her last or surname. Use of surnames also has a

practical value, for a midnight call from "Janet" may be recognized less quickly

than a call from "Janet Henderson" or "Mrs. Henderson." While conducting the

examination the physician should not think out loud, articulating possible

diagnoses, for needless and disturbing explanations may be required later.

Finally, the physician should evaluate the patient's attitude and make every

effort to adjust to it. Although some patients may appreciate a casual and relaxed

style, others are more comfortable and confident when the physician is serious and

formal. Patients will not alter or adjust their personalities to conform to the wishes

of the physician; any adjusting that is needed must be done by the physician.

The physician can do several things to reduce the patient's anxiety. First, the

history should be obtained in as comfortable and private a setting as possible; the

patient should be clothed and seated at the same level as the physician, especially if

she is meeting the physician for the first time. A patient may choose to change into

an examination robe before seeing the physician if the visit is for a follow-up

examination. Under most circumstances she should be interviewed alone.

Exceptions may be made for children, adolescents, and mentally impaired women,

or if the patient specifically requests that an attendant or family member be

present. Even in these situations it is usually a good idea to give her an opportunity

to speak with the physician privately.

Second, the initial portion of the interview should be designed to put the

patient at ease. This can often be accomplished by discussing neutral and

nonmedical subjects such as recent recreational activities, employment, or family.

This should not, however, be viewed merely as a means of relaxing the patient, but

rather as an opportunity for the physician to relate to the patient's psychological

and social dimensions.

Finally, the physician should not make assumptions about the patient's

background. For example, physicians usually assume that all adult female patients

are both sexually active and heterosexual. Either or both may not be true.

Therefore, asking neutral and open-ended questions (e.g., "Are you sexually

active?" or "Are you having sex with men?") will let the patient know that you

have not made these assumptions.

In addition to these aspects of the patient-physician interaction, patient

satisfaction is also related to the time required to get an appointment, the patient

mix in the reception area, the length of waiting time in the reception or

examination room, the attitude of the office staff, and the billing procedures.

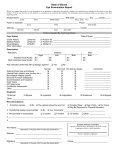

PATIENT HISTORY. When large numbers of patients are involved, as in a clinic

setting or in a very busy office, certain basic information (e.g., age, ethnic

background, marital status, obstetric history, and whatever the patient may want to

divulge about the problem for which she consults the physician) is often obtained

by interview with an office nurse or by a questionnaire the patient is asked to fill

out. Although these devices are sometimes considered essential, it is astonishing

how little time they really save; by obtaining these data personally the physician

provides a logical opening for the interview and establishes a preliminary rapport

with the patient. In addition, the manner in which she answers these mundane

questions may alert the physician to areas that should be probed more deeply.

The setting for the history taking is important. A quiet area in which

distractions (telephone calls, interruptions) can be kept to a minimum and in which

privacy is ensured promotes a comfortable dialogue between physician and patient.

The foundation for rapport in a continuing relation can be established during these

15 to 30 minutes of the initial history taking. This is perhaps the most critical time

the physician spends with most patients.

Overview

The history provides information about the total patient and is perhaps the

most important part of the gynecologic evaluation. It enables the woman to become

acquainted with the physician in a nonthreatening situation. In most cases it gives

the physician data to establish a tentative diagnosis before the physical

examination. In many respects the gynecologist who takes a history is like the

detective who keeps the various clues that are pertinent and discards those that are

deliberately or inadvertently misleading. If the gynecologic history is sufficiently

penetrating, it should in almost all cases permit the physician to narrow the likely

possibilities to one or at most two probable diagnoses. This preliminary opinion

may not always be correct, but the history-taking session should not be ended until

a tentative diagnosis has been made.

Like a hospital chart, the office history is a legal, as well as a medical, record.

As such, it is subject to subpoena, and whatever is recorded in it may at some

future date need to be defended in court. It should not contain extraneous or

casually written material, and the notes should be sufficiently complete that the

case can be readily reconstructed.

The gynecologic history should include the following information:

I. Presenting complaint

A. The primary problem

B. Duration

C. Severity

D. Precipitating factors

E. Occurrence in relation to other functions(menstrual cycle, coital activity,

gastrointestinal activity, voiding, or other pertinent functions)

F. Any previous similar symptom and itsdiagnosis and management

G. Change in normal life-style resulting fromthe complaint

H. Outcome of previous therapies

II. Menstrual history

A. Menarche

B. Frequency of menstrual periods

C. Regularity of menstrual flow

D. Date of onset of last menstrual period

E. Precipitating factors

F. Duration of flow

G. Degree of discomfort

H. Quantity of menstrual flow (number of pads used per day)

I. Premenstrual symptoms

J. Contraception (current and past methods)

K. Obstetric history

L. Number of pregnancies

M. Number of living children

N. Number of abortions, spontaneous or induced

O. History of previous pregnancies (duration of pregnancy, antepartum

complications, duration of labor, type of delivery, anesthesia used, intrapartum

complications, postpartum complications, hospital, physician) P. Perinatal status of

fetuses (birth weights, early growth and development of children, including

feeding habits, growth, overall well-being, current status)

III. Past medical history

A. Allergies

B. Medications currently used

C. Medical problems for which care has been required

D. Hospitalization

IV. Surgical history

A. Any operative procedures: outcome, complications

V. Review of systems

A. Pulmonary symptoms

B. Cardiac symptoms

C. Gastrointestinal symptoms

D. Urinary symptoms

E. Vascular symptoms

VI. Breast symptoms

A. Masses

B. Galactorrhea

C. Pain

D. Family history

VII. Social history

A. Exercise

B. Dietary habits

C. Drug use

D. Alcohol use

E. Smoking habits

F. Marital status

G. Number of years married

H. Coital activity (libido, dyspareunia, orgasm)

I. Occupational history (exposure to environmental toxins)

VIII. Family history

A. Significant medical and surgical disorders in family members

Presenting Complaint

It is best to begin the history with an open-ended question that will elicit any

symptoms the patient may have. Then ask the patient to describe the problem in

her own words. Less information will be obtained if the interviewer asks only

focused, closed-ended questions to which the patient can answer yes or no.

However, it is necessary for the interviewer to have an outline for questions about

the gynecologic history in order to obtain all the necessary information. The

following is a list of questions that are typical of a gynecologic history.

What were the circumstances at the time the problem began {time, place,

activity, cycles)? What has been the sequence of events? Often the use of a

calendar to refer to will aid the patient. Have you had this problem before? If the

patient answers yes, then ask for the description of the previous occurrence and

what led to its disappearance. To what extent is the problem interfering with your

daily life and the life of your family? Have you had previous evaluations or

treatments? Records from previous physicians may be helpful. Why did you seek

evaluation of the problem now? What questions do you want answered today?

What do you expect and want from today's visit?

Menstrual History

The cycle interval is counted from the first day of menstrual flow of one cycle

to the first day of menstrual flow of the next cycle. Many women count their cycle

from the end of one period to the beginning of the next.

The range of normal is wide, and a recent change in usual pattern may be a

more reliable sign of a problem than the absolute interval. Although 28-day cycles

are the median, only a small percentage of women have cycles of that length. The

normal range for ovulatory cycles is between 21 and 35 days. Cycle length remains

relatively constant over the reproductive years for each woman.

Estimation of the amount of menstrual flow by history is difficult. The

average blood loss is 30 ml, with a range between 10 ml and 80 ml. Birth control

method usually affects the amount of blood loss, for oral contraceptives cause a

decrease and intrauterine devices cause an increase. An increase in the number of

tampons or pads used (> one per hour for six or more hours) and the passage of

blood clots are signs of excessive blood flow.

Dysmenorrhea is common. It usually begins just before or soon after the onset

of bleeding and usually subsides by the second or third day of flow. The

discomfort is characteristically midline and is often associated with backache and,

in the case of primary dysmenorrhea, with systemic symptoms such as lightheadedness, diarrhea, nausea, and headache.

Sexual History

Although there are many models for sexual histories, most are not appropriate

for the nonpsychiatric physician or in the setting of a brief office visit. However, a

model for office practice has been developed and detailed by Munjack and Oziel,

who describe two types of sexual histories: a screening history and a problemoriented history. The screening history is brief, and suited for inclusion in the

comprehensive medical history that is often part of a patient's first visit to her

gynecologist. The problem-oriented history is more detailed, and designed to

investigate those problems identified by the screening history.

The screening history is designed to determine whether there are any major

sexual difficulties that need in-depth evaluation and therapy, and whether the

physician can deal with the problem or whether it should be referred elsewhere for

more intensive evaluation. In an attempt to put the patient at ease the physician can

begin the sexual history by prefacing his questions with statements such as, "Most

people experience ..." or "Because sexual problems can develop as part of other

gynecologic problems ..." In addition, if the physician can convey a willingness to

help, the patient is more likely to discuss any problems she may have. Finally, the

screening history should begin with a discussion of topics that are unlikely to

provoke anxiety. For example, questions about the occurrence of pain during

intercourse are less likely to cause anxiety than questions about orgasmic function

or noncoital sexual practices.

The problem-oriented sexual history should include the following topics:

Onset of the problem

Course of the problem

Conditions that decrease or increase the severity of the problem

Previous evaluation of the problem and the results of such evaluation

Previous treatment of the problem and the results of such treatment

Severity of the problem

Patient's reaction to the problem

Impact of the problem on the patient's sexual relationships

Patient's sexual attitudes and upbringing

Patient's sexual practices

Quality of patient's sexual and/or marital relationship

A rational treatment or referral plan can be formulated on the basis of

discussion of these and related questions.

In addition to obtaining a history of sexual dysfunction, it is also important to

obtain a history of any sexually transmitted diseases. The physician should

question the patient about past episodes of sexually transmitted diseases, sexual

practices, number of sexual partners, sociosexual background of sexual partners,

use of barrier forms of contraception, use of intravenous drugs, previous blood

transfusions, genital lesions, persistent vaginal discharge or pelvic pain.

General Medical History

Because many gynecologic patients want to conceive sometime in the future,

a general medical history and social history should also be obtained. Women

contemplating pregnancy benefit from prepregnancy counseling, and effective

counseling can be performed only when there is knowledge and identification of

medical and social conditions that place mother and fetus at risk. The following

medical and social conditions should be evaluated during the gynecologic history.

I. Genetic disorders

A. History of birth defects

B. History of habitual abortion

C. History of stillbirth or neonatal death

D. History of infertility

E. History of environmental exposure

Infections

X-rays

Drugs (e.g., lithium, alcohol, warfarin, retin A, anesthetic gases

F. History of consanguinity

G. Genetic disease in the mother

Sickle cell anemia

Porphyria

Phenylketonuria

Von Willebrand's disease

Myotonic dystrophy

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Monfaris disease

Chondrodystrophies

H. History of advanced maternal age

II. Endocrine and metabolic diseases

A. Diabetes mellitus

B. Thyroid disease

C. Obesity

D. Anorexia nervosa—bulimia

E. Galactorrhea

F. Hirsutism—acne

III. Cardiovascular disorders

A. Rheumatic heart disease

B. Congenital heart disease

C. Mitral valve prolapse syndrome

D. Ischemic heart disease

E. Venous thromboses and embolism

F. Hypertension

IV. Hematologic disorders

A. Inherited coagulopathies

Hemophilia carrier

Platelet defects

B. Red blood cell defects

V. Renal disorders

A. Polycystic disease

B. Chronic pyelonephritis

C. Congenital anomalies

D. Systemic lupus erythematosus

E. Renal transplantation

VI. Neurologic disorders

A. Multiple sclerosis

B. Neural tube defects

C. Spinal cord injuries

D. Myasthenia gravis

VII. Genitourinary disorders

A. Congenital mullerian anomalies

Diethylstilbestrol exposure

Fusion defects

B. Dysuria

C. Incontinence

D. Prolapse

VIII. Gastrointestinal disorders

A. Liver disease

B. Functional bowel syndrome

IX. Social factors

A. Alcohol use

B. Tobacco use

C. Recreational drug user

D. Occupational hazards

E. Dietary practices

Finally, the perimenopausal and postmenopausal woman has gynecologic and

medical problems that are unique to her age and require special attention. In

addition to the questions discussed above, the menopausal woman should be

evaluated for the effects of estrogen deficiency, including vasomotor symptoms,

vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, ischemic heart disease, and osteoporosis.

Questions about the patient's emotional status, social support system, financial

status, diet, and exercise level may also provide information that will aid in the

management of these unique menopausal problems.

THE GYNECOLOGIC EXAMINATION. It is important for the obstetriciangynecologist to know the physical condition of the patient. A complete physical

examination and appropriate laboratory tests should be performed at the first visit.

A complete physical examination may or may not be part of the subsequent office

visit of the gynecologic patient. For the woman in good health who has consulted

an internist recently or is under the care of an internist for some ongoing disorder

such as hypertension or diabetes, a complete physical examination may not be

needed. For the woman with an endocrine disorder, a complete physical

examination clearly should be part of the gynecologist's evaluation. The

designation of the obstetrician-gynecologist as a "primary physician for women" is

variously interpreted by the practitioners of this discipline. An important part of

this responsibility is referral to other physicians for such special examinations as

may be needed. Except for the breasts, which should be examined at every

gynecologic visit, the detail of the physical evaluation of gynecologic patients

varies according to the circumstances.

On entering the examining room the physician should make some brief

comment to put the patient at ease, but to expect the patient to "relax" is probably

out of the question. During the physical examination another woman participant,

usually a nurse or aide, must be present. Not only can this woman assist the

physician, but she also lends an element of psychological support to the patient.

Her presence is also of legal importance to the physician as a guard against

accusations that may be initiated by an unscrupulous or disturbed patient. The

dialogue between physician and patient should continue during the examination.

Distracting conversation with the nurse or aide tends to influence the patient

adversely and detracts from the physician-patient rapport.

Evaluation of General Appearance

Examination of the Head and Neck

Examination of the Cardiopulmonary System

Examination of the Breast

Examination of the Chest

Examination of the Abdomen

Examination of the Extremities

The Pelvic Examination

The first pelvic examination should probably take place in the neonatal

period. Certainly an examination is indicated at any time there is abnormal

bleeding, pelvic symptoms, or questions about primary or secondary sexual

development, or with the initiation of sexual activity. For the teenager the first

pelvic examination should probably occur between ages 18 and 21. Examinations

should then be repeated at yearly intervals at which time a Papanicolaou test (Pap

smear) should be performed in addition to a pelvic examination and a screening for

breast cancer and hypertension.

The pelvic examination provides the physician with an opportunity to dispel

myths and misunderstandings and to educate with respect to pelvic anatomy,

physical development, and sexual function. Often the patient is reassured if the

physician carries on a running dialogue with her describing the findings, asking

and answering questions, and, on occasion, demonstrating physical findings with

the aid of a hand-held mirror. There are several things a physician can do to

maximize the educational aspects of an examination. First, explain all procedures

in advance. Second, when possible, keep eye contact with the patient during the

examination. Third, give the patient choices when possible (e.g., whether or not to

use a drape, or the option to delay parts of the examination if discomfort is

encountered). Fourth, explain all findings clearly.

Patient Preparation

The pelvic examination is performed with the patient lying on her back with

both knees flexed. The buttocks are positioned at the edge of the examining table,

and the feet are supported by stirrups. This position allows the necessary exposure

to the pelvic organs.

Traditionally, the patient has been placed with the head and body in a

horizontal position. This position does not allow the physician to maintain eye

contact with the patient and increases the patient's sense of vulnerability. The

alternative, assuming the availability of an adjustable examination table, is to

elevate the head of the table between 30 and 90 degrees. There are no apparent

technical disadvantages to this alternate position, and many patients find it easier to

relax, actually making the bimanual part of the examination more accurate. The

patient should also empty her bladder just before the examination.

Equipment

The minimal equipment needed to perform a pelvic examination includes a

good light source, a speculum of the correct size, a nonsterile glove, and a watersoluble lubricant. Additional supplies that should be available in the examination

room include a variety of speculum sizes; materials to obtain cytologic samples,

including fixative; various culture media; large cotton-tipped swabs; pH indicator

paper; and a screening test for fecal occult blood (e.g., Hemoccult). Specialized

examinations require other specific equipment.

External Genitalia

The pelvic examination begins with inspection of the vulva. The physician

should note and record any evidence of developmental abnormalities as well as the

general state of cleanliness, discharge, hair growth and distribution, and any

abnormalities of the skin, including tumors, ulcerations, scratch marks, rashes, and

minor lacerations or bruises Any vulvar varicosities or hemorrhoids should also be

noted A careful inspection of the skin folds and the pelvic hair may also reveal

occult disease or infection The vulva should also be palpated for subcutaneous

lesions

The labia are then spread, and the condition of the hymen, size of the clitoris,

and condition of the vulvovaginal skin noted. The area of the Bartholin's, the

periurethral, and Skene's glands should be palpated, and the urethra should be

palpated along its length for a caruncle, diverticulum, or infection. After asking the

patient to contract the muscles of the vaginal opening to assess the tone of the

levator muscles and the degree of perineal support, the patient is asked to strain,

and the presence of a urethrocele, cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, or prolapse of

the vagina or cervix is noted.

Vaginal Examination. The vagina should first be inspected with the use of a

speculum Specula come in a variety of sizes, and an appropriate size should be

selected for the individual patient. Usually the largest size that is comfortable

provides the best visualization.

Painless insertion of the speculum may be aided by a number of techniques.

First, the muscles at the opening of the vagina may be relaxed by gentle downward

pressure with one or two fingers. The speculum may be moistened with warm

water before insertion, but other kinds of lubrication should be avoided if either

cultures or cytology is to be obtained. The speculum blades should be inserted

obliquely (but not vertically) through the introitus, immediately rotated to the

horizontal plane, and then slowly opened after reaching the vaginal apex The

vaginal walls and cervix should be inspected for lesions The vaginal discharge

should be assessed for volume, color, consistency, and odor. The endocervical

discharge should also be examined Samples for cervical or vaginal cytology,

cultures, and direct microscopic examination of the vaginal or cervical discharge

should be obtained as indicated. Before removal of the speculum the cervix should

be evaluated for ectropion, erosion, infection, discharge, laceration, polyps,

ulcerations, and tumors. As the speculum is removed and with the patient bearing

down, the degree of vaginal wall relaxation and uterine prolapse can be assessed.

With the speculum removed but with the patient still bearing down, one can

observe if the patient exhibits stress incontinence.

Generally, the physician should acquire proficiency with the index and middle

fingers of one hand and then always use that hand for the vaginal examination.

After the speculum has been withdrawn the physician should gently insert the

index and middle fingers along the posterior wall of the vagina. It is helpful to

place a stool at the base of the examining table and support the examining arm and

elbow during the examination. This support of the elbow allows greater sensitivity

m the examining fingers At the same time a second dimension is added by pressing

on the patient's abdomen with the other hand The first palpable structure is the

cervix. Next is the anteriorly placed uterine fundus The bimanual technique can

outline its position, size, shape, consistency, and degree of mobility. Uterine or

cervical mobility can be further assessed by placing the fingers on one side of the

structure and moving it to the contralateral side. This can be done on both right and

left sides to detect chronic or acute inflammatory changes and fixation. The

abdominal hand is then placed on one lower quadrant and slowly worked menorly

and medially to meet the examining fingers of the vaginal hand In this way adnexal

structures on that side can be appreciated The degree of adherence of an adnexal

structure to the uterus can be ascertained. Enlargement, consistency, and position

of ovaries and tubes can be noted. The ovary is a sensitive structure, and patients

differ in tolerance to palpation. The contralateral side should be similarly

examined. The glove of the examining hand is then replaced with a clean glove for

the rectovaginal examination.

Rectovaginal Examination. A pelvic examination is not complete without a

rectovaginal examination. Although the rectal examination is generally

uncomfortable, it can be less so if the physician places a finger gently into the anal

opening and waits for the anal sphincter to relax before proceeding. The middle

finger is inserted into the rectum and the index finger into the vagina. The

parametrial tissue is palpated between the index finger in the vagina and middle

finger in the rectum. Then the posterior uterine surface, the adnexal areas, the

uterosacral ligaments, and the pouch of Douglas, along with the anorectal area, are

palpated. The rectovaginal examination enhances the evaluation of the cul-de-sac

or ovarian pathology. Particles of hard fecal material may interfere with an

accurate examination.

Rectal Examination. Rectal examination is also useful when a vaginal

examination is impossible, such as in infants and children. The rectal wall is

palpated throughout its circumference and as far as the finger permits. Almost half

' of all rectosigmoid cancers can be detected by this palpation. The finger can also

explore the surface of each pelvic wall, feeling for enlarged nodes or other

abnormalities. The patient should be instructed to slide up on the table while the

lower third of the table is replaced. The examiner then carefully washes his hands

and advises the patient to get dressed. The physician should then step out of the

room to allow the patient to get dressed.

Postexamination Discussion. When the patient rejoins the physician in the

consultation room, diagnosis and findings should be explained in terms she can

understand. The implications of the findings should be carefully detailed. It is

occasionally helpful to have the patient paraphrase what the physician has said to

make certain she understands. This is especially relevant when surgery is

contemplated, for the nuances of an operation and its results may be unclear to the

patient. At this rime the use of medications and the duration of their use must be

explained. The physician should also carefully explain the symptoms that may be

expected after any treatment given during the office visit (e.g., heavy leukorrhea

after cryosurgery or bleeding after cervical biopsy). Advice against coitus should

be given when appropriate, and the duration of abstinence should be made clear.

The importance of a follow-up examination should be stressed. Prescriptions for

hormones should be adequately detailed and restrictions on refills explicitly stated.

DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES Pap Smear

The early diagnosis of cervical carcinoma is based on periodic cytologic

examination of the cervix. Despite extensive debates regarding the optimum

frequency and accuracy of the Pap smear, it has become the standard method of

screening for cervical carcinoma. In addition to detecting early cervical cancer, the

Pap smear can also assess hormonal status and identify sexually transmitted

pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Pap smears should be obtained at periodic intervals in all sexually active

women. Thereafter, they should probably be obtained yearly, especially in women

who have had coitus with more than one sexual partner, who began to have coitus

as an adolescent, or who has a history of a sexually transmitted disease. They

should be performed annually in women who have had a hysterectomy for pelvic

cancer or in situ disease, but are not necessary in women who have had a

hysterectomy for benign disease.

Colposcopy. Colposcopy aids the physician in the examination of the visible

portion of the female reproductive tract (i.e., vulva, vagina, and cervix). This

technique complements cytologic evaluation and can often localize the source of

abnormal cells seen on cytology. Vulvar diseases amenable to colposcopic

evaluation include human papillomavirus infections (HPV), herpes genitalis, and

preinvasive malignancies. The magnification afforded by the colposcope may aid

the surgeon in selecting areas to biopsy. The application of 3% acetic acid for three

to five minutes may also help to define abnormal areas that often turn white and

display sharp borders (so-called acetowhite epithelium).

The colposcope may also aid in the recognition of clinically inapparent

vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia or HPV infection. These lesions are also

characterized by acetowhite epithelium.

Endometrial Sampling. The recent introduction of new devices for endometrial

sampling has simplified the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. As a result,

the use of dilatation and curettage under general or regional anesthesia has been

replaced in many situations by outpatient endometrial biopsies. The result has been

a savings of money, time, and morbidity.

Before obtaining an endometrial biopsy the physician should obtain an

informed verbal or written consent from the patient. He should then rule out an

intrauterine pregnancy, cervical or endometrial infection, and cervical stenosis.

Patients with valvular heart disease should probably be given antibiotic

prophylaxis.

The size and position of the uterus are determined by a pelvic or ultrasound

examination, and a speculum is placed into the vagina. If the patient is sensitive to

cervical manipulation, a paracervical block can be administered. When endometrial

cancer is suspected an endocervical biopsy should be obtained before the

endometrial sampling. The cervix and upper vagina is then cleansed with an

antiseptic such as povidone-iodine (Betadine).

Vulvar Biopsy. In the past the toluidine blue test was used to direct vulvar

biopsies. The vulva was first washed with 1% acetic acid, dried and treated with

toluidine blue dye. After two to three minutes the dye was washed away with 1%

acetic acid. Areas of possible vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia retained the dye, and

thus guided the physician to suspicious areas for biopsy. Because of the high rate

of false positives and false negatives, the toluidine blue test has been largely

replaced by colposcopy.

The only definitive way to exclude invasion is to biopsy and microscopically

examine any suspicious area of the vulva. Fortunately vulvar biopsies are usually

simple to obtain in the office. The area under suspicion is first cleansed with an

antiseptic solution and infiltrated with 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) and a 25-gauge

needle. Then a 3- to 4-mm Keyes punch is used to obtain a biopsy specimen. Any

bleeding that occurs can be controlled with silver nitrate sticks or Monsel's solution

and gentle pressure. For larger biopsy areas a single interrupted suture obtains hemostasis.

Ovulation Detection. The confirmation of ovulation is often an important part of

the evaluation of patients with infertility or abnormal uterine bleeding. It is also

useful in timing donor and homologous artificial insemination.

Until recently the methods used to detect ovulation reflected progesterone

secretion by the ovary. Most popular among these was the determination of a

biphasic temperature pattern by recording the basal body temperature (BBT). The

BBT is the patient's temperature taken immediately on awakening and before any

activity. A shift and persistent elevation in the BBT of 0.5°F to 1.0°F in response

to the secretion of progesterone reflects ovulation. However, it reflects ovulation

after it has occurred and does not allow the patient to predict in advance when

ovulation is going to occur.

Others have used measures of serum progesterone or the presence of secretory

endometrium to confirm the occurrence of ovulation. These methods also provide

confirmation of ovulation but do not make it possible for the infertile patient to

predict the day of ovulation for the timing of coitus or insemination.

Serial ultrasound studies of follicular growth and disappearance and

subsequent formation of a corpus luteum is another method of detecting and timing

ovulation. The sonographic changes associated with ovulation include a

preovulatory follicle of 20 mm or more, a change in the shape of the follicle,

thickening of the follicular wall, disappearance of the follicle, and the appearance

of fluid in the cul-de-sac. However, these changes can occur without actual

ovulation, and ovulation can occur without these characteristic changes.

Unfortunately only direct observation of ovulation at laparoscopy, or pregnancy

provides definite evidence of actual ovulation.

Office Hysteroscopy. The development of small hysteroscopes that use carbon

dioxide as a distention medicine has made it possible to determine the cause of

abnormal uterine bleeding, the size and shape of the uterine cavity, the presence of

urogenital anomalies of the uterus, the location of a misplaced intrauterine device,

and the presence of intrauterine adhesions in the office setting, often without

anesthesia. As a result, dilatation and curettage and hysterosalpingography are no

longer always the primary procedure for the evaluation of abnormal bleeding or

intrauterine abnormalities associated with infertility.

The procedure is safe, simple, and quick. The procedure is performed early in

the menstrual cycle to avoid any intrauterine pregnancy or a thick endometrium.

After the patient signs an informed consent, the cervix is cleansed with an

antiseptic solution and a 4-mm hysteroscope sheath and a C02 hysteroscope is

inserted through the cervix, which is secured with a single-toothed tenaculum. The

insertion of the hysteroscope is facilitated by judging the size, shape, and flexion of

the uterus by performing a bimanual examination before the hysteroscopy.

IV. Control questions and tasks

1. What methods are used for special (gynecological) examination?

2. What woman’s position used for gynecological examination?

3. What tests are considered functional diagnostic tests?

4. What are endoscopic methods?

5. What are cytologic methods?

V. List of recommended literature

1. Danforth’s Obstetric and gynaecology.-Seventh edition.-1994.-P.691-708

2. Gynecology.-Stephan Khmil, Zina Kuchma, Lesya Romanchuk.-2003.P.13-25

3. Gynaecology illustrated. David McKay Hart, Jane Norman.-Fifth Edition.2000.-P.72-85

Approved on Session of Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with course

of Infant and Adolescent Gynecology_________________ protocol No________

T.a.The Head of Department:_______________ O.A.Andriiets’