Extremal properties of ray-nonsingular matrices

... values among its nonzero entries. Note that if x is strongly balanced, then so is each vector y obtained from x by appending on a new coordinate. The following gives another geometric condition, which is equivalent to x being balanced and is easily proved. Lemma 3.1. Let x be an m × 1 ray-pattern ve ...

... values among its nonzero entries. Note that if x is strongly balanced, then so is each vector y obtained from x by appending on a new coordinate. The following gives another geometric condition, which is equivalent to x being balanced and is easily proved. Lemma 3.1. Let x be an m × 1 ray-pattern ve ...

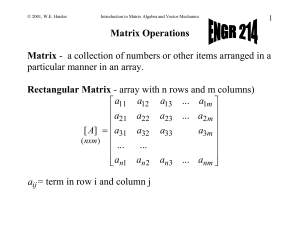

Matrices and Linear Algebra

... Theorem 2.2.3. Let A ∈ Mm,n (F ). Then the RREF is necessarily unique. We defer the proof of this result. Let A ∈ Mm,n (F ). Recall that the row space of A is the subspace of Rn (or Cn ) spanned by the rows of A. In symbols the row space is S(r1 (A), . . . , rm (A)). Proposition 2.2.1. For A ∈ Mm,n ...

... Theorem 2.2.3. Let A ∈ Mm,n (F ). Then the RREF is necessarily unique. We defer the proof of this result. Let A ∈ Mm,n (F ). Recall that the row space of A is the subspace of Rn (or Cn ) spanned by the rows of A. In symbols the row space is S(r1 (A), . . . , rm (A)). Proposition 2.2.1. For A ∈ Mm,n ...

Notes on Matrix Calculus

... of 0s and 1s, with a single 1 on each row and column. When premultiplying another matrix, it simply rearranges the ordering of rows of that matrix (postmultiplying by Tm,n rearranges columns). The transpose matrix is also related to the Kronecker product. With A and B defined as above, B ⊗ A = Tp,m ...

... of 0s and 1s, with a single 1 on each row and column. When premultiplying another matrix, it simply rearranges the ordering of rows of that matrix (postmultiplying by Tm,n rearranges columns). The transpose matrix is also related to the Kronecker product. With A and B defined as above, B ⊗ A = Tp,m ...

Review of Matrix Algebra

... diagonal (diagonal running from upper left to lower right) if aij a ji . For example, for a (3x3), we ...

... diagonal (diagonal running from upper left to lower right) if aij a ji . For example, for a (3x3), we ...

B Linear Algebra: Matrices

... in which x1 = x11 , x2 = x22 and x3 = x33 . Are x and X the same thing? If so we could treat column vectors as one-column matrices and dispense with the distinction. Indeed in many contexts a column vector of order n may be treated as a matrix with a single column, i.e., as a matrix of order n × 1. ...

... in which x1 = x11 , x2 = x22 and x3 = x33 . Are x and X the same thing? If so we could treat column vectors as one-column matrices and dispense with the distinction. Indeed in many contexts a column vector of order n may be treated as a matrix with a single column, i.e., as a matrix of order n × 1. ...

COMPUTING RAY CLASS GROUPS, CONDUCTORS AND

... 1.5 (2), we only need to compute pa /pb and the simplest way is probably as follows. Let p = pZK + πZK be a two-element representation of p, where we may assume π chosen so that vp (π) = 1 (if this is not the case, then vp (p) = 1, i.e. p is unramified, and hence we replace π by π + p). Then for all ...

... 1.5 (2), we only need to compute pa /pb and the simplest way is probably as follows. Let p = pZK + πZK be a two-element representation of p, where we may assume π chosen so that vp (π) = 1 (if this is not the case, then vp (p) = 1, i.e. p is unramified, and hence we replace π by π + p). Then for all ...

LECTURE 16: REPRESENTATIONS OF QUIVERS Introduction

... algebra A we mean a representation U that does not split into the direct sum of two nonzero representations of A. Clearly, any finite dimensional representation decomposes into the sum of indecomposable ones. The Krull-Schmidt theorem says that such a decomposition is unique. More precisely, we have ...

... algebra A we mean a representation U that does not split into the direct sum of two nonzero representations of A. Clearly, any finite dimensional representation decomposes into the sum of indecomposable ones. The Krull-Schmidt theorem says that such a decomposition is unique. More precisely, we have ...

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN THE DIFFERENT CONCEPTS We can

... the elements of Y with respect to x r s . When we turn to concept 1 we note that these partial derivatives all appear in a column of Y / X. Just as we did in locating a column of a Kronecker product we have to specify exactly where this column is located in the matrix Y / X. If s is 1 then the p ...

... the elements of Y with respect to x r s . When we turn to concept 1 we note that these partial derivatives all appear in a column of Y / X. Just as we did in locating a column of a Kronecker product we have to specify exactly where this column is located in the matrix Y / X. If s is 1 then the p ...

Jordan normal form

In linear algebra, a Jordan normal form (often called Jordan canonical form)of a linear operator on a finite-dimensional vector space is an upper triangular matrix of a particular form called a Jordan matrix, representing the operator with respect to some basis. Such matrix has each non-zero off-diagonal entry equal to 1, immediately above the main diagonal (on the superdiagonal), and with identical diagonal entries to the left and below them. If the vector space is over a field K, then a basis with respect to which the matrix has the required form exists if and only if all eigenvalues of the matrix lie in K, or equivalently if the characteristic polynomial of the operator splits into linear factors over K. This condition is always satisfied if K is the field of complex numbers. The diagonal entries of the normal form are the eigenvalues of the operator, with the number of times each one occurs being given by its algebraic multiplicity.If the operator is originally given by a square matrix M, then its Jordan normal form is also called the Jordan normal form of M. Any square matrix has a Jordan normal form if the field of coefficients is extended to one containing all the eigenvalues of the matrix. In spite of its name, the normal form for a given M is not entirely unique, as it is a block diagonal matrix formed of Jordan blocks, the order of which is not fixed; it is conventional to group blocks for the same eigenvalue together, but no ordering is imposed among the eigenvalues, nor among the blocks for a given eigenvalue, although the latter could for instance be ordered by weakly decreasing size.The Jordan–Chevalley decomposition is particularly simple with respect to a basis for which the operator takes its Jordan normal form. The diagonal form for diagonalizable matrices, for instance normal matrices, is a special case of the Jordan normal form.The Jordan normal form is named after Camille Jordan.