* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Succession to the caliphate in early Islam - PDXScholar

Muslim world wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Twelver Shia Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam and war wikipedia , lookup

Usul Fiqh in Ja'fari school wikipedia , lookup

Imamah (Shia) wikipedia , lookup

Satanic Verses wikipedia , lookup

Islam and modernity wikipedia , lookup

Islamic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Islamic culture wikipedia , lookup

Islam and secularism wikipedia , lookup

Husayn ibn Ali wikipedia , lookup

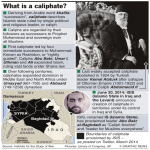

Succession to Muhammad wikipedia , lookup

Zanj Rebellion wikipedia , lookup

Reception of Islam in Early Modern Europe wikipedia , lookup

Egypt in the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Islamic ethics wikipedia , lookup

Islam and other religions wikipedia , lookup

Islamic schools and branches wikipedia , lookup

Schools of Islamic theology wikipedia , lookup

Islamic Golden Age wikipedia , lookup

History of Islam wikipedia , lookup