* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

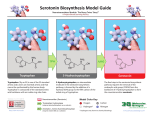

Download Serotonin synthesis, release and reuptake in terminals: a

Environmental enrichment wikipedia , lookup

Neurogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Activity-dependent plasticity wikipedia , lookup

Time perception wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychology wikipedia , lookup

Neurophilosophy wikipedia , lookup

Neuroplasticity wikipedia , lookup

Synaptic gating wikipedia , lookup

Brain Rules wikipedia , lookup

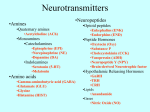

Neurotransmitter wikipedia , lookup

De novo protein synthesis theory of memory formation wikipedia , lookup

Agent-based model in biology wikipedia , lookup

Single-unit recording wikipedia , lookup

Mathematical model wikipedia , lookup

Neuroanatomy wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Holonomic brain theory wikipedia , lookup

Nervous system network models wikipedia , lookup

Biological neuron model wikipedia , lookup

Clinical neurochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Metastability in the brain wikipedia , lookup

Aging brain wikipedia , lookup

Biology of depression wikipedia , lookup