* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Humanist History as Moral Philosophy and the Secular Immortality of

Renaissance Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance architecture wikipedia , lookup

Art in early modern Scotland wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance music wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance in Scotland wikipedia , lookup

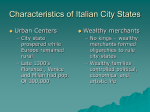

Italian Renaissance wikipedia , lookup

Spanish Renaissance literature wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance Humanism Part 2 Humanist History as Moral Philosophy and the Secular Immortality of Fame (also see my more general essay on Humanism) Robert Baldwin Associate Professor of Art History Connecticut College New London, CT 06320 [email protected] (This essay was written in 1990 and is revised annually.) Humanist History as Moral Philosophy From its start in the mid-fourteenth century, humanists placed new value on history as a worthy subject in modern education. In part, they were inspired by the rich historical writing of classical antiquity including Herodotus, Thucydides, Polybius, Sallust, Caesar, Curtius, Livy, Suetonius, Xenophon, Plutarch, and Tacitus, among many others. More importantly, they were inspired by the focus of classical historians on politics, morality, and broad social issues, the very focus of humanist culture. From the late fourteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, the most common rationale advanced for studying history was the examination of a "universal" human nature with respect to morality and politics. Humanist history was largely moral and political philosophy extending itself through time and geared toward the exercise of moral and political virtue in the present. Historical knowledge would allow urban elites, from republican citizens to lofty princes, to govern with greater wisdom and prudence. As the civic humanist and historian, Bruni, noted, in his essay on education, First amongst such studies I place History; a subject which must not on any account be neglected by one who aspires to true cultivation. For it is our duty to understand the origins of our own history and its development; and the achievements of Peoples and of Kings. For the careful study of the past enlarges our foresight in contemporary affairs and affords to citizens and to monarchs lessons of incitement or warning in the ordering of public policy. From History, also, we draw our store of examples of moral precepts. 1 With its focus on living figures from the past, humanist history claimed for itself a "natural" truth, that is, a wisdom grounded in the study of human nature. Since humanism defined human nature as universal and unchanging, the moral and political lessons from the classical past were directly applicable to modern problems and circumstances. In his Discourses on Livy (III.43), a commentary on Livy's history of Rome, the great Florentine civic humanist and republican statesman, Machiavelli, described this universal human nature and used it to justify the study of history in a chapter entitled, "That Men Born in One Province Display Almost the Same Nature in Every Age". Prudent men are in the habit of saying, neither by chance nor without reason, that anyone wishing to see what is to be must consider what has been: all the things of this world in every era have their counterparts in ancient times. This occurs since these actions are carried out by men who have and have always had the same passions, which, of necessity, must give rise to the same results. It is true that their actions are more effective at one time in this province than in that, and at another, in that rather than this one, according to the form of the education from which these peoples have derived their way of living. Understanding future affairs through past ones is also facilitated by observing how a nation over a lengthy period of time keeps the same customs, being either continuously avaricious or continuously deceitful, or having some other similar vice or virtue. ... 2 Repeated in discussions of history through the eighteenth century, 3 this view explains the common features shared by history and more imaginary forms of literature such as tragedy. For Renaissance humanists, and thus, for most educated elites in Italy after 1400, history offered a school of life, a moral guidebook, a grand series of "true" lessons, a rich compendia of "living" heroes and villains to be emulated and shunned like the figures in Plutarch’s Lives of the Illustrious Greeks and Romans. The pictorial equivalent of these histories of great men and women were Renaissance cycles of paintings of heroes and a few heroines such as those painted by Castagno (Villa Carducci), Perugino (Cambio), Joos de Ghent (for Fegerico da Montefeltro), Ghirlandaio (Palazzo Vecchio), and Mantegna, (Roman emperors in the Camera degli Sposi). 4 History also offered Renaissance civic and courtly patrons new ways to celebrate themselves, to define roots in a glorious antiquity, and to define political and ethnic geographies such as empires, kingdoms, and "nations" or "peoples". Imperial, monarchical, and aristocratic patrons commissioned histories imbedding themselves in a glorious imperial past of one kind or another with special reference to the Roman empire or the Hellenic empire of Alexander the Great. By 1475, most Italian Renaissance princes were celebrated in these humanist histories and epic poems (historical poetry). Republican patrons, magistrates, and historians, in turn, invented republican classical traditions, historical parallels, and ancestors for modern republics and republican heroes. One example was the Roman republican history developed for Florence in Bruni's Panegyric on Florence. Bruni's successor as chancellor of Florence, Poggio, wrote a long history of Florence in the 1440s. "National" histories began appearing in the sixteenth century. In his Oration in Praise of Germany (1501) given to the emperor, Maximilian I, the German humanist, Bebel, praised Maximilian as an historian writing a glorious history of Germany and compared him to Julius Caesar as a patron of arts and letters. 5 In 1561, the Florentine historian and political philosopher, Francesco Guicciardini, published a bestselling History of Italy. Its frequent reprintings between 1561-1600 with editions in every major European language shows how humanist historical culture spread rapidly across sixteenth-century Europe. Humanist World History: Cosmic Cycles and Linear Time Classical writers generally saw time in circular terms in conjunction with the cycles of the planets and stars, the seasons, and the alternation of night and day. At times, they described human history as a cycle of four progressive or declining ages which tended to revert back to the beginning. The four stages were wilderness, pastoral, agriculture, and city. In primitivist histories, mankind declined from a perfect, wilderness existence to a modern world of urban corruption and alienation from nature. The best example of this appears in the beginning of Ovid's Metamorphoses where the modern emperor Augustus brings back the lost Golden Age. In progressivist accounts, the stages advance from a savage wilderness to one of urban civilization, technological mastery, and high culture. Progessivist histories also followed cyclical patterns with their warnings of civilizations foundering and collapsing in corruption and returning to the first stage. See, for example, Polybius' Rise of the Roman Empire where he generalizes political history as a series of cycles imbedded in larger cosmic or natural time. 6 In sharp contrast, early Christian writers defined time as strictly linear, moving forward in an unbroken line from Creation until the end of human existence in Apocalypse, Last Judgment, and the eternities of heaven and hell. History and time were strictly subordinated to a Christian deity. Even when medieval writers divided human time into ages, they used a Christian scheme of three periods: life before Christ (the Jewish and pagan world), life during the time of Christ (New Testament), and life after Christ (the age of organized Christianity). While this medieval Christian "historical" thinking continued in Renaissance church culture, it was largely supplanted elsewhere by a new humanist history geared not toward Christ but towards a new terrestrial sense of time. For humanists, history divided into three very different periods unrelated to religion: a classical period of light and civilization which declined in later antiquity, a medieval period of supposed darkness and ignorance, and a modern humanist period of renewed civilization. Classical cyclical and progressive linear time both reappeared in Renaissance humanism. In part, cyclical ideas of history were necessary for Renaissance humanists to justify humanism as a whole. After all, humanism extolled classical civilization as an exemplary "Golden Age" useful for guiding the modern age. This was already clear in the critique of medieval linear time late advanced by the late fourteenth-century Florentine civic humanist, Salutati. … You would not, I am sure, deny that very many of the processes of Nature move in periodic cycles. The fourfold change of the twelve months follows the course of every year. We see first the beginnings of new birth renewed in the germinating earth; then with various changes we see these beginnings, warmed by the summer heat, shaping themselves into the abundance of the coming fruit; then, when they are ripe for the birth they give each its fruit in due season, and, by as much as they were warmed by the summer's heat, they are tempered by the autumn coolness; finally, in the depth of winter they are all drawn up into the bosom of the all-producing earth to return once more to their beginnings when the frost gives way to the warmth of spring. The same thing is plainly to be seen in the course of human affairs if one turns carefully the page of history; for, though nothing returns in precisely the same form, yet we see daily some image of the past renewed. ... 7 Cyclical history also appealed to humanists for other reasons. By imbedding the rise and fall of regimes and changes in social morality within the larger cycles of nature, humanists struggled to order the chaotic power struggles and reversals of fortune which plagued Europe in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. One of the most influential statements of this thinking came at the beginning of book five of Machiavelli's Florentine Histories. Usually provinces go most of the time, in the changes they make, from order to disorder and then pass again from disorder to order, for worldly things are not allowed by nature to stand still. As soon as they reach their ultimate perfection, having no further to rise, they must descend, and similarly, once they have descended and through their disorders arrived at the ultimate depth, since they cannot descend further, of necessity they must rise. Thus they are always descending from good to bad and rising from bad to good. For virtue gives birth to quiet, quiet to leisure, leisure to disorder, disorder to ruin; and similarly, from ruin, order is born, from order, virtue; and from virtue, glory and good fortune. Whence it has been observed by the prudent that letters come after arms and that, in provinces and cities, captains arise before philosophers. For as good and ordered armies give birth to victories and victories to quiet, the strength of well-armed spirits cannot be corrupted by a more honorable leisure than that of letters, nor can leisure enter into well-instituted cities with a greater and more dangerous deceit than this one. This was best understood by Cato when the philosophers Diogenes and Carneades, sent by Athens as spokesmen to the Senate, came to Rome. When he saw how the Roman youth was beginning to follow them about with admiration, and since he recognized the evil that could result to the fatherland from this honorable leisure, he saw to it that no philosopher could be accepted in Rome. Thus, provinces comes by these means to ruin; when they have arrived there and men have become wise from their afflictions, they return, as was said, to order unless they remain suffocated by an extraordinary force. These causes, first through the ancient Tuscans and then the Romans, have made Italy sometimes happy, sometimes wretched. 8 The appeal of circular time in no way diminished the appeal of linear time for Renaissance humanists. But here too, we see an important shift from medieval notions of linear time. Drawing on more optimistic classical notions of linear time as human progress and improvement, Renaissance humanists refashioned medieval linear time from an Augustinian sacred history moving from Creation to Last Judgment to a more terrestrial view of history where the past culminated triumphantly in modern knowledge and virtue and continued to move into a glowing future. 9 Humanism even managed to imbed linear time in nature by comparing the rise of civilizations to the linear stages of organic growth in trees, animals, and human life. Turning away from medieval sacred time and drawing on a variety of classical ideas, Renaissance humanism managed to combine circular and linear time. For example, the return to the beginning - classical antiquity - was also a historical step forward out of the "dark ages" toward a glorious, unfolding future. And when humanists hailed princes for restoring a lost golden age of civilization, peace, and prosperity, they usually praised a golden age which surpassed its predecessors. Painting as History: Image Cycles of Great Men From the early fifteenth century, humanist princes and magistrates in Italy began commissioning cycles of paintings and tapestries on the great historical figures of classical antiquity. Princely patrons favored rulers and world conquerors such as Alexander the Great, Caesar, Augustus, and Constantine. A Dutch artist painted a series of portraits of famous men for the study of the humanist duke of Urbino, Federigo da Montefeltro while Mantegna painted a cycle of busts of Roman emperors on the ceiling of the main reception room of the Duke of Mantua, Ludovico Gonzaga. Burgher patrons and the magistrates of republican city states like Florence commissioned cycles of republican heroes who stood up to princely tyranny. One such example was Ghirlandaio's cycle in the town hall of Florence, the Palazzo Vecchio. By the mid-sixteenth century, classical political history became an important new subject in European art at the highest levels of court and civic patronage. Other cycles of famous people from classical history focused on intellectuals like Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, and Homer. Among these was Raphael's famous School of Athens and Parnassus painted around 1508-1510 on the walls of the private library of Pope Julius II. Such cycles of great thinkers continued into the seventeenth century and included, among many examples, Rembrandt's Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer. Renaissance patrons also commissioned cycles of paintings and tapestries on figures who occupied a place in history and myth, in that exalted realm of early history where heroes interacted with the gods and realized glorious destinies guided by divine providence. Of these, none was more important than the story of the Trojan prince, Aeneas. According to Roman legend, Aeneas was the grandson of Venus. When the Greeks destroyed Troy at the end of the Trojan war, Aeneas fled the burning city carrying his old father, Anchises, on his back, and accompanied by his son. After a series of maritime adventures sailing the Trojan fleet around the Mediterranean, Aeneas started a new settlement at the mouth of the Tiber River in what is now Italy. Marrying into the local Latin tribe, the Trojans took on a new identity. His descendants included Romulus and Remus, fathered by Mars, who grew up to found Rome and led that town to early political power in central Italy. In this mythical history, Troy was more then just an ancestor kingdom for Rome in a universal court history of great kingdoms and empires linked by Divine Providence. In some sense, Troy was an early version of Rome before it became Rome, with bloodlines flowing directly from Trojan kings to later Roman kings and emperors, all descended from the Gods through Aeneas (and Romulus, the son of Mars). In the universal or world histories favored by rulers and Catholic church officials since the Renaissance, the decline of the kingdom of Troy was less a disaster than a divinely ordained prelude necessary for the rise of Rome as the greatest empire in history and the touchstone of all later Western kingdoms, empires, and nations aspiring to greatness. If this was already true to some extent in the Middle Ages, the story of Aeneas and the Troy-Rome narrative remained the most important foundation story for European monarchs, emperors, and popes from the Renaissance to the twentieth century. 10 Needless to say, it enjoyed special favor in the cultural patronage of high nobles and church officials in Renaissance and Baroque Rome. The Renaissance revival of classical historical values also gave new life to other classical heroes who founded great cities or empires such as Hercules and Alexander the Great. Every cycle of tapestries, paintings, or prints celebrating the great historical figures of classical antiquity had its own moral and political lessons, its own targeted audiences, and its own particular agenda grounded in local politics. Yet they all shared in the new humanist culture of history and fame. For all their backward looking imagery, they were geared toward defining the virtues of modern patrons, families, institutions, states, and cities and to "writing" them into a permanent and glorious place in a new historical culture. In so far as classical history entered European art at the highest social and political levels and appeared in works of the greatest scale and sumptuousness in the most prominent buildings and reception rooms, Renaissance art offered more than a passive reflection of the new humanist culture of history. By making history a permanent part of the material fabric of elite social, political, and cultural life, Renaissance art itself played a major role in defining and circulating the new historical values. The Secular Immortality of Fame In so far as history preserved for later audiences the best and worst of human nature, humanist history fueled a new sense of fame achieved through heroic worldly achievements and through supreme heights of virtue, generally externalized in some outer action. For many humanists, history offered a new kind of secular or terrestrial immortality, the immortality of fame. Here they drew on the rich historical culture of classical antiquity which frequently extolled the immortal fame won by the greatest public figures: athletes, rulers, warriors, explorers, founders of cities, and so on. Some women were occasionally included in these catalogues, usually for displaying extreme versions of traditional female virtues tied to the private sphere. Renaissance humanists also drew on classical ideas of the human mind as divine, as an eternal, celestial reality untouched by worldly disasters and death. To the extent that educated human beings lived the life of the mind and contributed to it, they could achieve a secular immortality through intellectual and cultural life. As the poet Horace wrote, "Art ensures, life is short" (Ars longa, vita brevis est). With its downgrading of worldly goals, achievements, and pleasures, medieval Christian culture ridiculed this classical culture of human fame, heroic accomplishment, and timeless intellect. In contrast to classical comments on the mind's triumph over death, medieval Christian writers loved to speak of the triumph of death over all worldly accomplishment and ambition, all wealth, power, beauty, and fame. This was particularly prominent in early Christian writing and in later monastic attacks on all "vainglory". Though medieval court culture continued elements of classical history and fame, it was largely overshadowed by this monastic hostility to worldly feats. All this took on greater urgency after the great Black Death of 1348 which killed one third of Europe and brought a heightened sense of penitence. In the wake of the Black Death, late medieval culture produced a rash of texts and images on the Triumph of Death and related themes. 11 Another late medieval image of death's power was the humorous "Dance of Death" where death mockingly carried away people from every station and occupation, high and low, triumphing over all. In sharp contrast to such late medieval values, Italian humanists began defending fame as a noble, worthwhile goal. For the early Florentine humanist and educator, Vergerio, the higher life of the mind found in the new humanist curriculum was inseparable from a new sense of heroic virtue and enduring fame. "We call those studies liberal which are worthy of a free man; those studies by which we attain and practice virtue and wisdom; that education which calls forth, trains and develops those highest gifts of body and of mind which ennoble men, and which are rightly judged to rank next in dignity to virtue only. For to a vulgar temper gain and pleasure are the one aim of existence, to a lofty nature, moral worth and fame. 12 The connection between fame and the new humanist ideals of civic political and moral engagement were particularly clear in the vigorous defense of fame advanced by one of the speakers in Alberti's On the Family (1430-34). Here we see how humanist fame was rooted in the Renaissance city and in the political, social, and economic ambitions produced by Renaissance city life. Lionardo: "So you see, Giannozzo, that the admirable resolve which would make private honor one's sole rule in life, though noble and generous in itself, may still be not the proper guide for spirits eager to seek glory. Fame is born not in the midst of private peace but in public action. Glory springs up in public squares; reputation is nourished by the voice and judgment of many persons of honor, and in the midst of people. Fame flees from every solitary and private spot to dwell gladly in the arena, where crowds are gathered and celebrity is found; there the name is bright and luminous of one who with hard sweat and assiduous toil for noble ends has projected himself out of silence and darkness, ignorance, and vice. For these reasons I have never felt that one should object to a man's seeking out by means of praiseworthy works and studies, but no less by a devout and careful adherence to good conduct, to gain the favor of some honorable and well-established citizen." ... "Also, Giannozzo, it is in the city one learns to be a citizen. There people acquire valuable knowledge, see many models to teach them the avoidance of evils. As they look around them they notice how handsome is honor, how lovely is fame, how divine a thing is glory. There they taste the sweets of praise, of being named and esteemed and admired. By these wondrous joys the young are awakened to the pursuit of excellence and come to devote themselves to attempting difficult things worthy of immortality. Such high advantages may not, perhaps, be found in the country amid logs and clods." 13 Given the new interest in "great" men and women from the classical past as examples and parallels for the modern age, it is not surprising to find an explosion of portraiture in Renaissance art. While the expansion of this aesthetic category was rooted in many developments including the new humanist sense of individual moral freedom, it was profoundly linked to the new culture of fame. In a certain sense, all Renaissance portraits were an attempt to secure fame through art. This was especially true for the mass-produced medallion portraits of princes which circulated throughout Italy and Europe after the 1430s and monumental portraits executed in fresco or sculpture for public spaces. Examples of the latter include the equestrian portraits of the fifteenth and sixteenth century: Uccello's Sir John Hawkwood painted on the wall of the Duomo in Florence (1430s), Donatello's Gattamelata (1445-50) placed by Venice in a conquered Padua, and Verrochio's Colleoni (1481-8) placed in a small square in Venice. It was also true for all Renaissance tomb portraits, painted and sculpted, starting with Masaccio's Holy Trinity and continuing all the way to Michelangelo's Medici Chapel. In later Renaissance tomb portraits, especially at the highest social levels where humanist fame was most securely entrenched, we see a remarkable change in the late medieval imagery of death after 1500. Instead of a triumphant death humbling pious donors praying for salvation to Christ, we begin to see tomb monuments extolling the heroic worldly deeds and virtues of the deceased and their secular triumph over death through eternal fame. One example was the relief depicting Terrestrial Fame from Andrea Riccio's Tomb of Giralomo and Mercantonio della Torre executed in the late teens. Here the sculptor carved an allegory of the triumph of human mind over death. Pegasus, the winged horse, appears as a traditional classical image of intellectual glory and eternal fame, along with a vase inscribed "Virtue," causing a nearby Death to drop his scythe in defeat. Fame's triumph over death appeared more explicitly in the tomb portraits of Michelangelo's Medici Chapel. There, the deceased rose triumphantly in eternal glory above their tombs like the resurrected Christ in the never-executed fresco toward which they gazed. Their ancient Roman armor and the "Four Times of Day" placed below them suggested an celestial triumph beyond time and space, an eternal, "Roman" fame. The Fame Bestowed by Art and the Elevation of the Writer and the Artist as Historical Agents One of the chief beneficiaries of the new humanist culture of history and fame were the writers and artists working to "write" the new history. Eternal fame required humanists, poets, painters, sculptors, and architects to write heroic virtues and accomplishments into the enduring record of history. As the Greek epic poet Pindar wrote in one of many self-conscious verses, "When men are dead and gone, it is only the loud acclaim of praise that surviveth mortals and revealeth their manner of life to chroniclers and to bards alike" 14 In his On Architecture, the ancient Roman architectural historian, and fame-seeker, Vitruvius, described three ways for artists to achieve fame: 1) by working for the greatest rulers, 2) by making art with conspicuous intellectual qualities, or 3) by teaching and writing about art. All three strategies were adopted by Renaissance artists. 15 From the beginning, Renaissance humanists and poets, and later artists, reminded their audience that they played a crucial role in writing and preserving history and creating fame. As early as the mid-fourteenth century, the Italian humanist poet, Boccaccio, insisted that great poetry lasted much longer than great empires or buildings and that poets "aspire to a glorious fame that shall endure to the end of time." 16 Poggio extended this to the visual arts in his dialogue, On Nobility, by having the character Lorenzo de' Medici defend the important role of art in securing fame. "I agree," Lorenzo replied, "that these qualities [reason, wisdom, virtue] contribute greatly towards gaining nobility and should be desired by all, for virtue is held to be a kind of divine thing. Nevertheless, we know that those who have paintings, varied and elegant sculptures, wealth, and abundance of possessions, or who hold public office and positions of power, have nobility bestowed on them, even though not noted for their virtue. We have read that highly intelligent people desired and respected such things. Even the most learned ancients spent much time and energy collecting sculptures and paintings. Cicero himself, Varro, Aristotle, and other Greeks and Romans, people extraordinarily learned in all fields, who displayed their virtues by taking refuge in their studies, adorned their libraries and gardens with such items in order to ennoble those places and display their own fame and praiseworthiness. They thought that visible examples of those who had a zeal for fame and wisdom would help ennoble and excite the mind. ... the external goods you rejected earlier, such as courtyards filled with statues, galleries, theaters, public entertainments, hunting, parties, and similar things that bring us public esteem, should be added to the person worthy of this title. These things make people famous and bestow nobility. Just as renown is a part of virtue and accompanies good deeds, so a distinctive name and fame beyond the ordinary arises from this renown - called nobility. The illustrious deeds and virtues which earned nobility for one generation are passed on to the next generation, like a light making them more distinguished and acclaimed. ... If we want future generations to remember and celebrate our deeds, then the recollection and glory of our parents, like their statues, must shine in those of us to whom we they wish to bequeath their fame. 17 Though Poggio used the austere civic humanist, Niccolo Niccoli, to rebut such material expressions of fame, Niccolo nonetheless endorsed the larger culture of fame as the reward of virtue. Around the same time as Poggio, the Florentine humanist, architect, art critic and moral writer, Alberti, offered a more aggressive defense of the lofty role of art in securing fame and in carving out a serene, inner world of mind safe from the "shipwreck" of worldly disaster. “There are other activities in which powers of body and mind function together to bring profit. Such are the occupations of painters, sculptors, musicians, and others like them. ... [The arts] remain with us and do not go down in shipwrecks but swim away with our naked selves. They keep us company all our lives and feed and maintain our name and fame.” 18 By the sixteenth century, some writers debated whether writers and artists were the primary agents of glory and wondered if any of the heroic acts described in the Iliad or Odyssey would have been famous if not for the poetic genius of Homer. In short, the new culture of history opened up new possibilities for Renaissance writers and artists to glorify their own work, increase a growing self-consciousness of literary and aesthetic effects, and enhance the literary and visual literacy of educated elites. Though one Pope Clement VII Medici ordered the death of Michelangelo after he built fortifications to defend republican Florence against a papal army, Clement quickly rescinded his decree, knowing Michelangelo was far more valuable alive than dead. Michelangelo himself suggested the enduring fame conferred by art when he defended his Medici tomb portraits against the criticism they were not lifelike. In two hundred years, he said, no one would know what the Medici looked like. The subtext was that his works were more important than any patrons and had their own higher, aesthetic worth which would outlive the historical reputation of his patrons. Here, it was the artist who reaped the rewards of fame, not the glorified patron. The Anxiety of Humanist History and the Continuation of Medieval Death The rise of a humanist historical culture did not mean the end of traditional medieval values. Instead, the two clashing cultures existed side by side, each reinforcing the "truth" of the other. The interplay of the two cultures was productive culturally, in creating new ambiguities, tensions, and contradictions in late medieval and humanist culture. For example, the rise of a courtly culture of eternal fame and glory strengthened monastic and burgher critiques of all vainglory. And the popularization in the sixteenth century of triumph of death and dance of death imagery helped fuel doubts within humanist culture, especially burgher culture, about the value of fame and glory. Even the earliest burgher proponents of humanist fame like Alberti displayed reservations tied to concerns rooted in late medieval culture (and classical critiques of fame). Thus, the other speaker in Alberti's On the Family expresses doubts about the superiority of urban life with its ambition and fame vs. the countryside which he associates with a wise and contented tranquility. Giannozzo: "I have some doubts, for all that, Lionardo, as to which is better, to bring up one's children in the country or the city. But let us assess it thus: every situation has its own natural advantages. In the city are the workshops of great dreams, for such are governments, constitutions, fame. In the country we find peace, contentment, a free way of pursuing life and health." 19 Doubts about fame even penetrated into a category of culture most readily associated with the new humanist fame, Renaissance epic poetry which served to immortalize the most glorious and heroic deeds of courtly heroes. In Tasso's Jerusalem Liberated (1575), a nymph warns the young men against the dangers of ambition. O young men, now while April and May are clothing you in green and blossoming array, ah let not the deceitful glitter of glory and virtue seduce your tender minds! ... Fools, why do you cast away the precious gift of your fresh youth, that is so short? Names and idols without substance are that which the world calls reputation and valor. Fame, that enchants you prideful mortals with a pleasing sound, and seems so beautiful, is an echo, a dream, the shadow of a dream, that with every wind is scattered and vanishes away. 20 Since the purpose of Tasso's epic was to immortalize the heroic liberation of Jerusalem from Turkish armies by Christian knights, the nymph's warning did not mean Tasso was a late medieval critic of the new humanist culture of heroic ambition and fame. On the contrary, Tasso was one of its most conspicuous proponents. But because he lived in a world which included an ongoing late medieval critique of ambition, especially unbridled, reckless ambition (which classical authors also attacked), Tasso felt it necessary to criticize fame in a poem which exemplified it. Whether he was protecting himself from external criticism or whether he harbored personal doubts about fame is difficult to tell. The important point to make here is that cultural innovations - for example humanist history and fame - invariably produce external criticism, internal doubts, and cultural ambiguities. As late as the seventeenth century, when humanist history was a well-established in education and elite culture, one sees a new interest in allegorical images of "Vanitas," that is, the emptiness and transience of all worldly pleasure, wealth, accomplishments, and fame. At a time when humanist history and fame reached a new level of extravagance in court culture, as at Versailles, vanitas imagery took on new prominence in Baroque religious art and in burgher secular imagery (as in the Netherlands). 1 2 Pp. 351-352 3 In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), the English Enlightenment philosopher and historian, David Hume repeated the view that history explored the unchanging, universal qualities of human nature. It is universally acknowledged that there is a great uniformity among the actions of men, in all nations and ages, and that human nature remains still the same, in its principles and operations. The same motives always produce the same actions. The same events follow from the same causes. Ambition, avarice, self-love, vanity, friendship, generosity, public spirit: these passions, mixed in various degrees, and distributed through society, have been, from the beginning of the world, and still are, the source of all the actions and enterprises, which have ever been observed among mankind. Would you know the sentiments, inclinations, and course of life of the Greeks and Romans? Study well the temper and actions of the French and English: You cannot be much mistaken in transferring to the former most of the observations which you have made with regard to the latter. Mankind are so much the same, in all times and places, that history informs us of nothing new or strange in this particular. Its chief use is only to discover the constant and universal principles of human nature, by showing men in all varieties of circumstances and situations, and furnishing us with materials from which we may form our observations and become acquainted with the regular springs of human action and behaviour. This is quoted in Beth Wright, Painting and History During the French Restoration, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 17, with other similar texts. 4 There was already a late medieval version of this in cycles on the Nine Worthies such as that painted by Jacquerio in the Castello di Manta. 5 6 7 8 Also see Francesco Guicciardini, Ricordi, Series B, no. 114, in Francesco Guicciardini, Maxims and Reflections of a Renaissance Statesman, trans. Mario Domandi, ed. Nicolai Rubenstein, Harper and Row, 1965, p. 123 9 10 See David Quint, Epic and Empire, Princeton Un Press, 1993; Richard Waswo, From Virgil to Vietnam, Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1997 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20