* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Ethnicity in the United States - American College Health Association

Fetal origins hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Birth control wikipedia , lookup

Women's health in India wikipedia , lookup

Medical ethics wikipedia , lookup

Women's medicine in antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Rhetoric of health and medicine wikipedia , lookup

Patient safety wikipedia , lookup

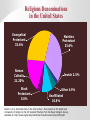

Cultural and Spiritual Views on Birth Control and Pap Smears Mary Lopes, ARNP Cathy Locke, CMA Presenters Reference Paul D. Blumenthal, MD, MPH Ethnicity in the United States US Census Bureau. Population Projections. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/popproj.html. Religious Denominations in the United States Evangelical Protestant 33.6% Mainline Protestant 33.6% Roman Catholic 21.20% Black Protestant 5.0% Jewish 2.5% Other 4.9% Unaffiliated 10.8% Bader C, et al. American Piety in the 21st Century: New Insights to the Depth and Complexity of Religion in the US: Selected Findings from the Baylor Religion Survey. Available at: http://www.baylor.edu/content/services/document.php/33304.pdf. Religious Beliefs About Contraception: Roman Catholicism • The purpose of marriage is procreation • Artificial contraception is wrong because it: Breaks the natural connection between the procreative and the punitive purposes of sex Damages the institution of marriage • The only permitted form of birth control is natural family planning (e.g., periodic abstinence) British Broadcasting Corporation. Religion & Ethics: History of Christian Attitudes to Birth Control. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/christianethics/contraception_2.shtml. Religious Beliefs About Contraception: Protestantism Beliefs about birth control are based on different Christian interpretations of the meaning of marriage, sex, and family In general, Protestant denominations let believers use birth control as their consciences dictate Evangelical churches consider birth control to be controversial – from opposition to all methods to opposition to any methods that prevent implantation of fertilized eggs British Broadcasting Corporation. Religion & Ethics: History of Christian Attitudes to Birth Control. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/christianethics/contraception_2.shtml. Religious Beliefs About Contraception: Judaism Jewish tradition values childbearing; “be fruitful and multiply” ◦ The obligation is fulfilled with birth of a son and a daughter ◦ The obligation is directed to men; women are the conduit Many rabbinic authorities permit contraception when pregnancy would seriously harm the woman Methods that prevent the “spilling of seed” – condoms, some female barrier methods, coitus interrupts, male and most female sterilization methods - are not permitted Methods that cause bleeding or spotting affect intimacy and quality of marital life. The woman must verify that there has been no recurrence for the 7 days following the end of bleeding Laws and adherence differ for Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Judaism Purnell LD, Paulanka BJ. Transcultural Health Care: A Culturally Competent Approach. 1998. Religious Beliefs About Contraception: Islam Marriage is not equated with conception The Qur’an does not mention contraception ◦ The sayings of the Prophet Mohammed tolerate coitus interruptus (azl), with the permission of the wife, who is also entitled to full sexual pleasure ◦ Contraceptive methods that temporarily prevent pregnancy are analogous to azl and are permissible In Islam there is a prioritization on the quality of life ◦ Planned birth spacing allows the mother the opportunity to care for each child Contraception is supported for economic reasons; to protect the life of the wife; to preserve the attractiveness of the wife for the enjoyment of the marriage; and to provide for the needs of the children Lawrence P, Rozmus C. J Transcult Nurs. 2001;12:228-233. Basic Values of Major Cultures in the United States Values American Hispanic African-American Control of Environment Look out for your own interests first Events happen by luck, fate, or powers beyond one’s control Determined and competitive in situations that threaten survival Change Change equals progress and growth Preservation of traditions Change equals progress and growth; education is an instrument of change Time Time is of the essence Being late is socially acceptable Self-help Achieving goals on your own Do what is best for Solutions/advice sought others of others Clutter AW, Nieto RD. Ohio State University Fact Sheet: Understanding the Hispanic Culture. Available at: http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/5000/5237.html; Pew Hispanic Center: Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. 2002 National Survey of Latinos: Survey Brief: Assimilation and Language. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/Assimilation-and-Language-2002-National-Survey-of-LatinosSurvey-Brief.pdf; Scott HJ. The African American Culture. Available at: http://appserv.pace.edu/emplibrary/VP-THEAFRICANAMERICANCULTURE_Hugh_J_Scott.pdf. Basic Values of Major Cultures in the United States (Continued) Values American Hispanic African-American Gender “All men are Father is head of created family; mother is equal” responsible for home Commitment to social justice and equality Relationships The individual is unique and precious The extended family – la familia – is the most important social unit “Family” is more than genetic kinship: parents depend on “family” to teach/discipline children Interactions Informality, directness, honesty Formality, manners, honor, respect for authority and elders Respect for elders; maintenance of harmony; reliance on oral traditions Tradition important; church influences family life Community and tradition important; religion woven into fabric of life Rituals and Religion Clutter AW, Nieto RD. Ohio State University Fact Sheet: Understanding the Hispanic Culture. Available at: http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/5000/5237.html;Pew Hispanic Center: Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. 2002 National Survey of Latinos: Survey Brief: Assimilation and Language. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/Assimilation-and-Language-2002-National-Survey-of-LatinosSurvey-Brief.pdf; Scott HJ. The African American Culture. Available at: http://appserv.pace.edu/emplibrary/VP-THEAFRICANAMERICANCULTURE_Hugh_J_Scott.pdf. Power Imbalances Affect the Use of Contraceptives in Different Cultures Power imbalances account for much of the underuse of contraceptives among women from different cultures ◦ In one study, two-thirds of men surveyed in the United Arab Emirates objected to the use of contraception by their wives ◦ Some married Latino women report using birth control without their husbands’ knowledge, fearing disapproval or accusations of infidelity ◦ Many Bolivian women avoid contraception because of disapproval by their husbands Ghazal-Aswad S. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;28:196-200; Arroyo L, Pinzon LA. Entre Parejas: An Exploration of Latinos’ Perspectives Regarding Family-Planning and Contraception. Available at: http://www.nclr.org/content/publications/detail/40994; Schuler SR, et al. Stud Fam Plann. 1994;25:211-221. Ethnic Differences in Beliefs About Condoms and Their Use* AfricanAmerican (n=589) Belief Hispanic (n=502) Mean SD Mean SD It is embarrassing to put on a condom 4.35 1.12 3.93 1.29 After sex, it is sometimes hard to find a good way to get rid of the condom 4.34 1.20 3.83 1.41 It is embarrassing to buy condoms 4.13 1.36 3.64 1.52 People only use condoms with people that they don’t want to be close to 4.04 1.40 3.67 1.50 Condoms are messy 3.58 1.50 3.00 1.50 Condoms often come off in the vagina or anus 2.84 1.47 3.10 1.43 Condoms often break 2.24 1.32 2.60 1.37 *Responses were scored on a 5-point scale: 1= strongly agree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = strongly disagree. Mean responses for African-Americans and Hispanics were significantly different at P<0.02. Norris AE, Ford K. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:39-53. Common Differences Between the United States and other Cultures Excessive deference to authority figures Male-female power imbalances A sense of fatalism Embarrassment regarding reproductive organs and/or contraceptive use Counseling African-American Women About Contraception • Holistic/spiritual Acknowledge the collective wisdom and experience • Communal Use social network – family, church, and community groups – to support goals • Awareness Build self-confidence; sense of self-control Create an awareness of symptoms Focus on long-term personal goals Eiser AR, Ellis G. Acad Med. 2007;82:176-183. Counseling Hispanics About Contraception 50 P=0.003 for Hispanics vs. Others 37.8 40 30 20 16.7 12.5 10 0 Whites Proctor A, et al. J Reprod Med. 2006;51:377-382. African Americans Hispanics Identifying Cultural Barriers Among African Americans The “conspiracy” theory that contraception is a way of controlling African-American reproduction Adolescent and unplanned pregnancies are more acceptable Thorburn S, Bogart LM. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:474-487; Horn B. Nurse Pract. 1983;8:35, 39, 74. Identifying Cultural Barriers Among Hispanics • Language barriers Varying levels of English proficiency Many dialects of Spanish spoken Literacy deficiencies • Deep-rooted religious beliefs and values Women should be sexually naïve Speaking about sexual practices should be avoided Fatalismo – events are meant to happen • Role of male as provider (machismo) Cooperation and/or approval of the head of the family is required before health care can be sought Fear of discussing safe sexual practices so as not to be perceived as unfaithful or untrusting – If economically dependent, fear of domestic violence • Distrust of health-care providers Sangi-Haghpeykar H, et al. Contraception. 2006;74:125-132; Scott CS, et al. Adolescence. 1988;23:667-688; Cuellar I, et al. J Commun Psychol. 1997; 25:535-549; Pew Hispanic Center, Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. 2002 National Survey of Latinos: Survey Brief: Assimilation and Language. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/Assimilation-and-Language2002-National-Survey-of-Latinos-Survey-Brief.pdf. Counseling Strategies: Active Listening On average, clinicians interrupt approximately 18 seconds after patients begin speaking Once interrupted, patients rarely attempt to continue expressing their concerns If patients are allowed to speak without being interrupted, it takes no more than 150 seconds for them to complete their statement of concerns Other studies have shown that failure to ask for a patient's agenda significantly reduces the clinician’s understanding of the problem Beckman HB, Frankel RM. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:692-696; Marvel MK, et al. JAMA. 1999;282(10):942-943; Rhoades DR, et al. Fam Med. 2001;33:528-532; Dyche L, Swiderski D. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:267-270. Preferred Family Planning in Russia • Abortion still preferred choice • Attempting to slow abortion rate • Rapid decline • Modern contraception use • Market as a healthy alternative Cultural Sensitivity in Gynecology The ultimate patient-centered care Reference: M. Elson, M.D. Clin Assoc Prof Ob/Gyn University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine What is the difference between cultural sensitivity and cultural stereotyping? Cultural stereotyping presumes that individuals within any given community think and behave the same way. Cultural sensitivity respects and responds to the health beliefs, practices, cultural and linguistic needs of the individual. The Iceberg model Above the Water Line • Habitus • Visible impairment • Posture/coordination • Mannerisms • Hygiene • Dentition • Skin color/race • Gender • Dress/hairstyle • Fluency in language of interaction • Piercings Below the Water Line • Non-visible impairment/learning disability • Occupation • Education • Religion • Sexual orientation • Political persuasion • Citizenship/national origin • Income/economic status • Interests • Native language • Family situation Far more lies beneath the water line than above-- Medicine as culture? •Language? •Customs? •Beliefs? •YES! Medical School’s Hidden CurriculumCultural Insensitivity • What students come to “know” and “understand” Scientific rationality • Emphasis on objectivity • Value measurements and physiochemical data • Objectify the patient’s own desire or body part • Community member or whole person • Other Significant Cultural Barriers to Health Care • Modesty • Medical decision making authority Individual may not be empowered to make decisions regarding care In some cultures poor prognosis is never shared with patient • Lack of understanding of belief system • Cost, often other barriers to care Common Across All Cultures • Nervous in clinical or unfamiliar environments • Reluctant to question providers • Language barriers heighten sense of helplessness and loss of control “Help Me To Understand” When There Seems to be a Barrier- ASK Sometimes there is no way to know what is happening The patient and family are looking for respect and sensitivity—they do not expect miraculous intuition Help me to understand why you aren’t taking your ____?? High vs. Low Context Cultures High Context -Meaning of individual behavior and speech changes depend on situation -Non-verbal messages are full of important meaning -Interpretation of messages dependent on relationship of sender and receiver, time and site of communication • China • Korea • Japan • Iran • Saudi Arabia • Mexico • Latin America High vs. Low context cultures Low Context • Intentions are expressed verbally • Context conveys little or no information • Words are shortest route from here to there • Individualistic, explicit and direct • Independent individuals • Germany • USA • Scandinavia • Swiss Low Context Communication • Nothing filtered • Mirrored, or a shared experience Mistranslation • Introduced in the U.S. • “Creap” coffee creamer (Japan) • “Super Piss” car lock de-icer (Finland) • Introduced in Latin America • The Chevy “Nova” Avoid Cultural Stereotyping •Do not presume that individuals within any given community think and behave the same way. •There are more differences between individuals in a given group than there are between groups Not different from them, different like them CULTURAL BARRIERS TO HEALTH CARE; ARABS •Medical care and provider •Gender •Privacy Female Muslim Patients • Under normal circumstances, a female Muslim patient is examined by a female Muslim doctor or a female non-Muslim doctor • However, if the case of a serious medical problem, it is permissible for a male doctor to examine and treat the female Muslim patient, observing her privacy rights Dr. Hamed Ghazili, Imam and Supt, Iman Academy Schools Islamic American University Three Privacy Rights for Female Muslim Patients • Khalwa-a male doctor may not examine a female patient without a chaperone. • Awra- no part of the body is exposed unless there is a need to do so. • No physical contact by male medical staff except as required for medical treatment. Dr. Hamed Ghazili, Imam and Supt, Iman Academy Schools Islamic American University Exceptions to the Three Conditions • “Necessities and emergencies make the prohibited permissible” • Life is precious and valuable in the sight of God and should not be endangered Dr. Hamed Ghazili, Imam and Supt, Iman Academy Schools Islamic American University Muslims • Muslims are persons who practice the organized religion of Islam. They come from various countries, vary widely in ethnicity, and speak many different languages. As with most other groups, individuals vary in beliefs and amounts of assimilation. Muslim culture is paternalistic, so women might expect to have a male protector sign consent forms. If necessary, explain US legal requirements, and after meeting HIPAA and other confidentiality requirements, the male may countersign the consents and forms if the client desires it. Since the left hand is considered less clean, use your right hand for palpation as much as possible. Even if you are left handed, use your right hand to give papers or medications to the client. Muslims especially value modesty and privacy. To keep as much of the body covered as possible, suggest removing as few clothes as necessary, or provide a sheet to wrap about the lower body and legs, in addition to a gown. During the month of Ramadan, religious fasting (includes water, food, smoking, sex) from before dawn until sunset may prevent adults from taking medications during daylight hours (have exceptions for pregnancy, illness, etc.). Reversible contraceptives are permitted, but tubal ligation or vasectomy usually is not. Abortion may be permitted under some circumstance, and usually before 120 days after fertilization. Muslim women may be adversely affected by breakthrough bleeding, since it may prevent praying (similar to menses).[1] [1]Best, K; Menstrual Changes Influence Method Use, Network, 19:4–9, 1998. Buddhism In Buddhism, there is no established doctrine about contraception. Traditional Buddhist teaching favors fertility over birth control, so some are reluctant to tamper with the natural development of life. A Buddhist may accept all contraceptive methods but with different degrees of hesitation. The worst of all is abortion or ‘killing a human to be.’ Korea http://depts.washington.edu/pfes/CultureClues.htm What are the Korean culture's norms about touch? Understanding Norms About Eye Contact and Body Language. Do not expect sustained direct eye contact. When you first meet your patient he or she may frequently look at you when you are not looking to become more comfortable. Handshakes are appropriate between men; women do not shake hands. Respect is shown to authority figures by giving a gentle bow. Understanding Personal Space Your patient may highly value emotional self-control, appearing stoic. Be aware that your patient may not show pain or ask for pain medications. Instead of asking your patient about pain, ask, "May I get you something for pain?" Respect of your patient's desire to keep emotions in control when asked about upsetting matters. Understanding Norms About Modesty Consider the modesty of women and girls when giving a pelvic exam. Many young women are modest about having an exam and may prefer a female doctor to do it. In some cases, your patient may refuse a gynecologic exam from a provider of either gender. Before you begin a gynecological exam, it is important to ask your patient, "May I examine you?" Ask your patient if she prefers a female doctor, attendant, or interpreter to remain in the room during the exam. Vietnam http://depts.washington.edu/pfes/CultureClues.htm What are the Vietnamese culture's norms about touch? Understanding Personal Space Handshakes are appropriate between men; women do not shake hands. Respect is shown to authority figures by giving a gentle bow and avoiding eye contact. Your patient may highly value emotional self-control, appearing stoic. Be aware that your patient may not show pain or ask for pain medications. Instead of asking your patient about pain, ask, "May I get you something for pain?“ Be respectful of your patient's desire to keep emotions in control when asked about upsetting subject matters. Some elder or new immigrant patients may consider the head sacred. Avoid touching it unless necessary. If an exam or procedure requires head care, let your patient know in advance. Some patients may feel protected if the opposite side of the head or shoulder is also touched. When examining your patient, do a head-to-toe assessment to honor the highest, most important part of the body first. Understanding Norms About Modesty Consider the modesty of women and girls when giving a pelvic exam. Many young nulliparous women are modest about having an exam and may prefer a female doctor to do it. In some cases, your patient may refuse a gynecologic exam from a provider of either gender. Before you begin a gynecological exam, it is important to ask your patient, "May I examine you?“ Ask your patient if she prefers a female doctor, attendant or interpreter to remain in the room during the exam. China http://depts.washington.edu/pfes/CultureClues.htm What are the Chinese culture's norms about touch? Understanding Norms About Eye Contact and Body Language Respect is shown to authority figures by giving a gentle bow and avoiding eye contact. Nonverbal cues are an important part of communication. For example, smiles when appropriate may be one way to build rapport. Your patient may highly value emotional self-control, appearing stoic. Be aware that your patient may not show pain or ask for pain medications. Instead of asking your patient about pain, ask, "May I get you something for pain?“ Be respectful of your patient's desire to keep emotions in control when asked about upsetting subject matters. Understanding Norms About Modesty Consider the modesty of women and girls when giving a pelvic exam. Many young women are modest about having an exam and may prefer a female doctor to do it. In some cases, your patient may refuse a gynecological exam from a provider of either gender. Before you begin a gynecological exam, it is important to ask your patient, "May I examine you?" Ask your patient if she prefers a female doctor, attendant, or interpreter to remain in the room during the exam. Vivien Hanson, MD. Reproductive Health, Clinical Practice Guidelines, Protocols on CDROM, 2008 From: Vivien Hanson mailto:[email protected] or questions to [email protected] Be Sensitive, and Ask: What do you call this problem? What do you think causes this problem? What do your family or friends say about the problem? How have you managed it? Native Americans and East Asians tend to be stoic about pain, while many Arabs and Hispanics believe suppressing or hiding pain makes the problem worse. Many Hispanics and traditional Chinese believe the blood supply is finite and some Hispanics believe drawing blood steals the soul or brings ill health. Chinese women often believe that sex after delivery will damage the body and that they must wait 100 days to resume sex. •Be especially careful to explain what you are doing during the physical examination to avoid misunderstanding. Taking blood pressure or examining the breasts when the client complains of vaginal discharge may be confusing to the client. Ask permission, especially when examining the vagina. Muslims Since the left hand is considered less clean, use your right hand for palpation as much as possible. Value modesty and privacy Contraceptives are permitted, but tubal ligation or vasectomy usually is not. Muslim women may be adversely affected by breakthrough bleeding. Religions Catholic, Jewish and Muslim • Religion also may create cultural barriers or differences, especially around sexuality and reproductive issues. Members of religious groups have varied levels of devotion, orthodoxy, and beliefs. Despite pronouncements of the church, Catholics in the US use contraceptives at the same rate as other groups and many accept abortions. • An orthodox Jewish woman must avoid sex during and for seven days after menses. Her husband may not touch her during this time and she needs to have a ritual bath before they resume sex. For these women, contraceptive methods or conditions that cause spotting or irregular bleeding may be of great concern, yet hormonal contraceptives may be preferred to barrier methods. Contraception Outrage Amy is a 32 year old woman who is 14 days postpartum after an uncomplicated vaginal birth. On the day of her postpartum visit the nurse asked Amy about her plans for contraception. Amy replies that she doesn’t need any. When the provider says she’ll write a prescription for contraception “Just in case you want to start”, Amy becomes furious and leaves the appointment. Contraception Outrage Amy and her partner Katie have been in a committed monogamous relationship for ten years Their baby was conceived by donor insemination This information was in the prenatal record •As with all patient contacts, approach the interview showing empathy, openmindedness, and without rendering judgment. • Intake forms should use the term “relationship status” instead of “marital status” including options like “partnered”. When asking-on the form or verbally- about a patient’s significant other, use terms such as “partner”, in addition to “spouse” and/or “husband/wife” •Adding “transgender” option to the male/female check boxes on your intake form can help capture better information about transgender patients, and will be an immediate sign of acceptance to that person •Prepare now to treat a transgender patient someday. Health care providers’ ignorance, surprise, or discomfort as they treat transgender people may alienate patients and result in lower quality or inappropriate care, as well as deter them from seeking future medical care. • When talking with transgender people, ask questions necessary to asses the issue, but avoid unrelated probing. Explaining why you need information can help avoid the perception of intrusion, for example:” To help asses your health risks, can you tell me about any history you have had with hormone use?” • When talking about sexual or relationship partners, use gender-neutral language such as “partner(s)” or “significant other(s).” Ask openended questions, and avoid making assumptions about the gender of a patient’s partner(s) or about sexual behavior(s). Use the same language that a patient does to describe self, sexual partners, relationships, and identity. When assessing the sexual history of transgender people, there are several special considerations: 1. Do not make assumptions about their behavior or bodies based on their presentation; 2. Ask if they have had any gender confirmation surgeries to understand what risks behaviors might be possible; and 3. Understand that discussion of genitals or sexual acts may be complicated by a disassociation with their body, and this can make the conversation particularly sensitive or stressful to the patient. •Ask the patient to clarify any terms or behaviors with which you are unfamiliar, or repeat a patient’s term with your own understanding of its meaning, to make sure you have no miscommunication •It is important to discuss sexual health issues openly with your patients. Nonjudgmental questions about sexual practices and behaviors are more important than asking about sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. Be aware that sexual behavior of a bisexual person may not differ significantly from that of heterosexual or lesbian/gay people. They may be monogamous for long periods of time and still identify as bisexual; they may be in multiple relationships with the full knowledge and consent of their partners. However, they may have been treated as confused, promiscuous, or even dangerous. They may be on guard against health care providers who assume that they are “sick” simply because they have sexual relationships with more than one sex. Yet they may also, in fact, lack comprehensive safer-sex information that reflects their sexual practices and attitudes, and may benefit from thorough discussions about sexual safety. Screenings and Health Concerns • Provide the age-appropriate screenings to lesbians and bisexual women that you would offer to any woman in your practice. Remember to focus on actual behaviors and practices more than your patient’s lesbian or bisexual identity when discussing risk, especially regarding sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Fertility and Pregnancy •Do not assume that the lesbian in your office has no plans to bear children, or that she has never been pregnant. Papanicolau “pap” Screening Pap smears are no less important for lesbians and bisexual women that they are for heterosexual women. Human Papilloma virus (HPV) can be transmitted among women who exclusively have sex with women. Women who partner with women may also have (past or present) had sexual contact with men. Unfortunately, many lesbians and some health care practitioners mistakenly assume that lesbians are not at risk for HPV, cervical cancer, and that Pap smears are unnecessary. STD Screening Most sexually transmitted diseases and infections can be transmitted by lesbians’ sexual practices. In addition, women who identify as lesbian may have had male sexual partners (past or present), or have experienced sexual abuse. Additionally, do not assume that older lesbians are not sexually active or that they do not need STD screening or safer sex information. Women can “come out” or begin sexual relationships with women at any age. WSU Demographics in Females #1 White #2 Asian American #3 Hispanic #4 African American #5 Native American Specific Approaches and Subcultures • Attractive culture • Other subcultures • Contraception worries, weight gain, moods, acne and concerns about chemical interference etc. “Many women’s health related handouts for selected Asian populations are found here” http://spiral.tufts. edu/index.html http://ethnomed.org/ •Culture Specific Pages Amharic •Cambodian •Chinese •Eritrean •Ethiopian •Hispanic •Hmong •Karen •Oromo •Somali •Tigrean •Vietnamese •Other groups •Cross Cultural Health Clinical Topics •Community HouseCalls •Cultural Competency •Immigration •Patient Education •Pearls of Cross Cultural Care •Related Sites •About Ethnomed EthnoMed •Copyright •Contribute Here is a good website to find health information in any language: http://healthlibrary.stanford.edu/reso urces/foreign/ Suggested Reading • Special Issues in Women’s Health, ACOG (2005) Patient Communication Cultural Competency, Sensitivity, and Awareness in the Delivery of Health Care • Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Women’s Health ACOG Committee Opinion #317 (2005) • Health Literacy ACOG Committee Opinion #391 (2007) www.acog.org Summary • Although health care is increasingly guided by scientific, evidence-based models, people are often guided by their religious/cultural beliefs, which are anything but evidencebased • Concepts of family planning and contraceptive use can challenge deeply held cultural and religious beliefs about sex, parenting, and gender roles • Beliefs and attitudes may create barriers to contraceptive use • Counseling should focus on identifying beliefs that are barriers to contraception and offer information that will help patients overcome these barriers Thank you!