* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Classification:

Urinary tract infection wikipedia , lookup

Sociality and disease transmission wikipedia , lookup

Common cold wikipedia , lookup

Childhood immunizations in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Sarcocystis wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Plasmodium falciparum wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Schistosoma mansoni wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

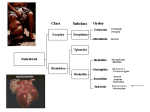

Wuchereria bancrofti A. Classification: Phylum: Nematoda Family: filaridae Genus and Species: Wuchereria bancrofti Common name: (bancroftian filariasis) Common Disease name – Filariasis or elephantiasis B. Morphology: Adult worms are long and slender with a smooth cuticle and bluntly rounded ends. The head is slightly swollen and bears two circles of well-defined papillae. The mouth is small and lacks a buccal cavity. The male is about 40 mm long and 100 um wide. Its tail is fingerlike. The female is much longer and measures around 6 to 10 cm long and 300 um wide. The vulva is near the level of the middle of the esophagus. After mating, the female viviparously (a method of reproduction in which the embryo develops inside the body of the female from which it gains nourishment) produces microfilaria (L1). The filariform juveniles or microfilaria are 1.4 to 2 mm long and in the L3 stage are infective to the definitive host. Figure 1: Male left, female right. Figure 2 and Figure 3: Infective stage of Wuchereria bancrofti, or microfilaria (L1) as seen in a blood smear. Note the sheath and characteristic V-spot near the head and tail. 1 C. Life Cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti: An individual first comes into contact with this parasite when a human is bitten by a mosquito infected with L3 larvae. The L3 larvae penetrate into the bite wound and go into the blood. They migrate to the nearest lymph gland and mature into adults. It takes anywhere from 3 months to 1 year for the larvae to develop into a dioecious adult. The adults can live 5-10 years in the host. The adult females then produce and birth sheathed microfilariae that migrate into lymph and blood channels of the human host. This parasitic infection is spread when an appropriate mosquito host ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal. Most microfilariae have nocturnal periodicity. After 2 to 6 hours in the mosquito, the microfilariae shed their sheaths and migrate through the cardiac portion of the misquitos midgut into the thoracic muscles of the mosquito. While within their muscles, the microfilariae develop into L1 without reproduction and eventually into third-stage infective larvae (L3) after approximately 2 weeks. The L3 moves into the mosquito's head and position themselves in the mouth parts or poboscis of the mosquito so that when the mosquito takes another blood meal, the infective larvae will be able to migrate into another human host. 2 Culcicine (left) or anopheline (center) mosquitoes are the main vectors of the nocturnally periodic forms of W. bancrofti, while day biting Aedes polynesiensis (right) transmit the subperiodic form in various pacific islands D. Geographic Distribution: W. bancrofti is widely distributed in tropical or subtropical regions (41N. latitude to 31S. latitude). Nocturnally periodic forms occur indigenously in almost every tropical and subtropical country and are very widespread. W.bancrofti and B.malayi infect some 128 milion people, and about 43 million have symptoms. Its distribution includes China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, SouthEast Asia, Sri Lanka, Tropical Africa, Central and South America, Pacific Islands. E. Pathology and Symptoms: There are 4 recognized stages of this disease: 1. The incubation period of 3 to 12 months in which there are no symptoms. 2. The acute symptomatic stage in which some swelling of the extremities may occur and this may be accompanied by pain, weakness of arms and legs, headache, insomnia. Fever is usually not present. 3. There is a period of recovery, which is permanent if re-infection does not occur. 3 4. If there is continued re-infection the cycle repeats and elephantiasis may result. Elephantiasis is characterized by the gross enlargement of a limb or areas of the trunk or head. There is an abnormal accumulation of watery fluid in the tissues causing severe swelling. The skin usually develops a thickened, pebbly appearance and may become ulcerated and darkened. Fever, chills and a general feeling of ill health may be present. Image 1 and 2: Elephantiasis of the leg due to Wuchereia bancrofti The worms in the lymphatic system cause tissue changes which restrict normal flow of lymph and result in swelling, fibrosis and eventually secondary infections in the affected tissues. The adult worms can live for several years. The lower extremities and groin are the parts most likely to be affected. Image 3 and 4: Elephantiasis of the groin due to Wuchereria bancrofti Following infection with third stage larvae there is usually a period of vigorous immune response to the invading larvae. Various pathologies associated with filarial infection arise from immune reactions to their presence. The most pronounced of these is the damage to the lymphatic vessels, which is mediated by the immune system's response to the adult worms living in them. These immune responses are characterized by inflammation of the affected area, which are usually extremities, and fever. The microfilariae in the blood and lungs can also cause an IgE-mediated allergic response which results in asthma-like symptoms. This condition is called "tropical eosinophilia". 4 F. Diagnosis: Until recently, diagnosing lymphatic filariasis had been extremely difficult, because it required detection of the microflariae in the blood. The “nocturnal periodicity” of the parasites in most parts of the world restricted their appearance in the blood to only the hours around midnight. However, the new development of a very sensitive and specific simple "card test" is used to detect circulating parasite antigens without the need for laboratory facilities and using only finger-prick blood droplets taken anytime of the day. There are a number of other methods used for diagnosis: ultrasonography has made it possible to visualize adult filarial worms within human lymphatic vessels. Lymphatic Imaging may also be performed. This reveals the patency in the main vessels of the lower limbs and may show that the para-aortic vessels are dilated. Also, the detection of filarial antigen can be done in order to indicate if there is a presence of circulating filarial antigen in the peripheral blood, with or without microfilariae. A urine examination and microscopy can be performed and urine should be examined macroscopically for the milky appearance of lymph and it can then concentrated for microfilariae. Image 5: Ultrasonography of the scrotum of a 20-year old male from Brazil with bancroftian filariasis. B-mode (left) and M-mode (right) show dilated lymphatics containing nematodes G. Treatment of individual Two main drugs that are used for treatment: diethylcarbamazepine (DEC) and ivermectin. Diethylcarbamazine and ivermectin are effective against microfilariae and adults. Ivermectin is a potent anthelmintic with a broad spectrum of activity against nematodes. After being taken orally, it is well absorbed in the blood. It causes muscle paralysis in parasites through affecting the ion-channels in cell membranes. Also, the drug albendazole is usually taken concurrently with one of the two drugs listed above. Usually, the primary goal of treating an entire affected community is to eliminate microfilariae from the blood of infected individuals so that transmission of the infection by the mosquito can be interrupted. Recent studies have shown that the use of single 5 doses of albendazole with DEC or ivermectin, administered concurrently, (is 99% effective in removing microfilariae from the blood for a full year after treatment. Besides the use of drugs, there are other means of treatment such as surgery. Large hydroceles and scrotal elephantiasis can be managed with surgical excisions. Surgical removal of infected tissues is done in order to improve lymph flow. However, the correction of gross limb elephantiasis with surgery is less successful. Also, pressure bandages are applied to reduce swelling H. Public Health Strategies There is no vaccine for filariasis. There are prevention centers on mass treatment with anti-filariasis drugs to prevent ingestion of larvae by mosquitoes, public health action to control mosquitoes, and individual action to avoid mosquito bites. Some tips on how to avoid being bitten by mosquitoes are: stay inside between dusk and dark when mosquitoes are most active in their search for food. When outside wear long pants and long-sleeved shirts, and spray exposed skin with an insect repellent. The strategy of the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis has two primary goals: first, to stop the spread of infection by interrupting transmission, and second to alleviate the suffering of affected individuals. To interrupt transmission of the infection, the entire at risk population needs to be treated for a period long enough to ensure that levels of microfilariae in the blood remain below those necessary to sustain transmission. For the yearly, single-dose, 2-drug regimens are being advocated. This is albendazole [400 mg] plus diethylcarbamazine [6 mg/kg]; or albendazole [400 mg] plus ivermectin [200 mcg/kg]). The recommended period is at least 5 years, corresponding to the reproductive lifespan of the parasite. For the treatment regimen based on the use of DEC-fortified salt, the period has been found to be 12 months of daily fortified salt intake. To alleviate suffering and decrease the disability caused by LF disease, the principal strategy focuses on decreasing secondary bacterial and fungal infection of limbs or genitals whose lymphatic function has already been compromised by filarial infection. It is this secondary infection that has recently been identified as the primary pathogenetic determinant of worsening lymphoedema and elephantiasis. Operationally, a regimen of hygiene to affected areas and the creation of hope and understanding among the patients and their communities are the principal strategic approaches. In 1998 the global healthcare company SmithKline Beecham collaborated with the World Health Organization in elimination efforts. This included the donation of numerous resources, especially albendazole, one of the mainstay drugs in the elimination strategy, free of charge, for as long as necessary to ensure success of the elimination programme. These donations, coupled with the recent decision by Merck and Co., Inc., to expand its ongoing Mectizan (ivermectin) Donation Programme to include treatment of lymphatic filariasis and the creation of additional partnerships with other private, public and international organizations, including the World Bank, have all further strengthened the potential for success of these elimination efforts. 6 Bibliography “Blood, Bone marrow, Spleen and Lymphnodes parasites” Carlo Denegri Foundation. Accessed 25 February 2005. <http://www.cdfound.to.it/html/bru1.htm> “Brugia malayi Wuchereria bancrofti.” University of Texas at Dallas. Feb. 28, 2005. <http://nsm1.utdallas.edu/bio/gonzalez/lecture/micro/brugia.htm> “Filariasis” Division of Parasitic Diseases. Accessed 25 February 2005. <http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Filariasis.asp?body=Frames/AF/Filariasis/body_Filariasis_w_bancrofti.htm> “Lymphatic filariasis.” World Health Organization. September 2000. 28 February 2005. <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs102/en/> “The strategy underlying the Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis.” The Global Alliance to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. 28 February 2005 <http://www.filariasis.org/index.pl?iid=1743> “Ultrasonography.” Tropical Medicine Central Resource. 28 February 2005 <http://tmcr.usuhs.mil/tmcr/chapter26/clinical4.htm> “Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi.” University of California at Davis: Department of Nematology.<http://ucdnema.ucdavis.edu/imagemap/ nemmap/Ent156html/nemas/wuchereriabrugia>. “Wuchereria bancrofti.” GPnotebook.28 February 2005 <http://www.gpnotebook.co.uk/cache/13303745.htm> “Wuchereria bancrofti: The causative agent of Bancroftian Filariasis.” Smith College. 1 January 1996. Accessed 25 February 2005. <http://maven.smith.edu/~sawlab/fgn/pnb/wuchban.html> Hillary Shields Adam Wimer Marjilla Seddiq (Spring 2005) 7