* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download THE SNAKE THAT ATE ITSELF L ONCE THE BREADBASKET OF AFRICA, ZIMBABWE IS

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Foreign-exchange reserves wikipedia , lookup

Helicopter money wikipedia , lookup

Great Recession in Russia wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Modern Monetary Theory wikipedia , lookup

Non-monetary economy wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup

Inflation targeting wikipedia , lookup

Exchange rate wikipedia , lookup

Real bills doctrine wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

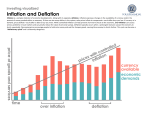

ZIMBABWE | ICAEW ■ THE SNAKE THAT ATE ITSELF ONCE THE BREADBASKET OF AFRICA, ZIMBABWE IS TENTATIVELY EMERGING FROM ECONOMIC CATASTROPHE L ast month’s announcement that UK inflation had risen to 4% prompted unease about the country’s fragile economy and criticism of the Bank of England’s interest policy. This acerbic reaction might have met with bemusement from observers elsewhere. In Zimbabwe, for example, normal trading was almost impossible by the end of 2008 due to the incredible rate of inflation, calculated by one report to be at an annualised percentage rate of 6.5 quindecillion novemdecillion – that is to say 6.5 followed by 107 zeros (way worse than the mere 409,000% we had feared – see Accountancy August 2007 p112) Even the authorities, which had clung to the belief that inflation could be controlled by pricing legislation, were starting to concede that the battle was lost. They began to ACCOUNTANCYMAGAZINE.COM | APRIL 2011 permit limited trading in foreign currency for those with special licences. Previously, trade in other currencies had been viewed by the government as ‘economic sabotage’ punishable by confinement in a disease-ridden jail without access to lawyers. In February 2009, the acting minister of finance legalised pricing and payment in foreign currencies. Such a high inflation rate hits different areas of the economy in different ways. Currency transactions split into two kinds: actual folding money was used for most transactions large and small, while money ‘in the bank’, which could only be moved by transfer (a letter of instruction taking the place of a cheque), was used for large transactions, tax settlement and investment activities. Eventually, the latter option became only possible in a narrow slice of the economy, including the stock exchange and tax payment. 105 ■ ICAEW | ZIMBABWE Money was being ‘printed’ for both methods, but at different speeds. For the cash market, banknotes eventually reached a denomination of 100 trillion ‘Zim’ dollars. It was an ironic blessing that printing more banknotes was ultimately limited by printing capacity, ink and paper supply, and time. Unfortunately, in the bank market, no such limitation existed. The central bank could ‘print’ money by simply writing a journal entry indicating that money had been transferred. This situation allowed Zimbabwe to achieve such a mind-boggling level of inflation. TWO INFLATION RATES The result was two co-existing inflation rates. Inflation in the ‘bank’ sector was higher than in the ‘cash’ sector, eventually approaching 100% a day. The Zim dollar had, in effect, become two currencies with, at one point, a ‘cash’ dollar worth 250bn ‘bank’ dollars. International Financial Reporting Standards presuppose some basic conditions including a logical relationship between inflation rates, exchange rates and interest rates. Clearly, when US$10 (£6.17) can buy either Z$10,000 or Z$2,500 trillion, and when exchange rates differ around the country, accounting presents an interesting challenge. The oft-touted ‘report in US$’ is meaningless with that translation range. One result was the collapse of the tax system. By the time payments in arrears were being collected, they were too small to have meaning. The central bank effectively became the taxing authority by printing money and giving it to the government, essentially taxing the money in the population’s pockets and in the banks, causing the destruction of savings. Another source of government funds was the official exchange rate. Exporters would sell produce for US dollars and be entitled to retain 70% of the proceeds as US dollars. However, they were required to ‘sell’ 30% to the government at the official exchange rate (a tiny fraction of the real rate). This was more of a tax system than a rate of exchange. Connected individuals profited hugely by buying US dollars at this rate, but few exporters could shoulder a tax burden of 30% of gross income - exports withered. Anything denominated in Zimbabwe dollars was halving in value each day. This kind of snake quickly eats itself. WHO WAS TO BLAME? With the economy in freefall, the official position was that the country’s woes were due to western sanctions. However, government economic policy was the major factor in the catastrophe. Policy makers were economically illiterate but believed themselves infallible. Important decisions were made by people with political clout but no idea of how an economy worked. Only a minority had the technical competence to see the problems ahead and advice from international organisations and locally-based experts alike was ignored. Any criticism was treated as political rather than factual. The governor of the Reserve Bank issued several public warnings as did a couple of ministers of finance. The former was cowed into silence while the latter were vilified as traitors. Examples of the Zimbabwean government’s economic incompetence abound. Printing money was publicly cited at the highest levels as brilliant, not because ‘quantitative 106 ‘It was an ironic blessing that printing more banknotes was ultimately limited by printing capacity, ink and paper supply, and time’ easing’ would provide market stimulation, but because printing notes somehow directly increased national wealth. When inflation resulted, price controls were introduced without any attempt to address the cause. The result was that the shops emptied and formal business ground to a halt. Staggeringly, when it was decreed that the price of beef in the shops should be reduced by 50%, it came as a complete surprise that farmers (ironically including most senior politicians and the authors of the decree) would be paid less for their cattle. In another bizarre episode, when a n’anga (a traditional healer/witchdoctor) claimed to have discovered purified diesel oil pouring from a plastic pipe on a hillside, the nation was told that it had the potential to save the economy. Ministers rushed to bestow her with gifts to curry favour. WHERE NEXT? So where are we now? Zimbabwe now has a government of national unity. This marriage of inconvenience does not work well politically, but the related infighting and bickering largely means that there is limited government interference in business and so recovery is taking hold. GDP growth last year was about 8.5% and may increase in 2011. Zimbabweans find the change miraculous in its speed and its extent. The introduction of foreign currencies has removed the government’s primary instrument with which it could abuse the economy: printing money can no longer be used to reallocate wealth from the productive to the parasitic. The shops are full of local and imported goods, there is fuel in the filing stations and prices are largely stable. The stock exchange has grown fourfold in US dollar value and brave early investors have made handsome real gains. Jobs are being created, but without much net gain as some businesses are failing. Danger lies in ZANU PF’s belief that it must maintain the illusion of infallibility and deny accountability to protect its position of power. Concern remains about what it might do to cling to power. However, it now suffers from a huge economic credibility gap. It absolved itself of any culpability and entirely blamed western sanctions for the economy’s collapse. Nevertheless, the truth is there for all to see: the economy is now recovering quickly despite the alleged sanctions, strongly suggesting that sanctions were not the primary cause. Although reverting to the failed policies of the recent past would undoubtedly be political suicide, these policies made some people very rich and a return cannot be ruled out. Generally, however, business believes that damage resulting from such short-term populist measures would be apparent early enough to allow a u-turn before too much harm was done. A temporary return would be a mere stumble on the upward slope of recovery. A warning: It should be noted that those of us still doing business in Zimbabwe are optimists. The author of this article is a member of the Global Accounting Alliance working in Zimbabwe. A previous article was published in August 2007 p112. ICAEW is working with local bodies around the world to help build capacity in the financial and accounting sectors. For details, call Mark Campbell on +44 (0)20 7920 8448 or visit www.icaew.com/capacitybuilding (see also ICAEW in Tanzania p88) APRIL 2011 | ACCOUNTANCYMAGAZINE.COM