* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Discover Fall 2007

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

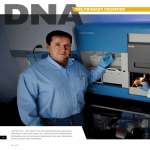

Explor i ng r esearc h at th e U n iversity of N ebraska M edical C enter discover UNMC an d beyon d... miniature surgical robots explore the inner human body Fa l l 20 07 discover UNMC Fa l l 2 0 0 7 exploring research at the construction, research growth continue University of Nebraska Medical Center and beyond... We value your opinion and welcome letters to the editor. Please send your letter to Discover Editor, UNMC, 985230 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 681985230. Letters will be verified before they are printed. UNMC Discover is published twice a year by the Vice Chancellor for Research and the Department of Public Affairs at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Issues of the magazine can be found at www.unmc. edu, News link. Permission is granted to reprint any written materials herein, provided proper credit is given. Direct requests to [email protected]. UNMC enjoys full accreditation (of all its colleges, programs and sites) by The Higher Learning Commission and is a member of The North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, 30 North LaSalle Street, Suite 2400, Chicago, IL, 60602-2504. Phone: 800-6217440 or www.ncahigherlearningcommission.org The University of Nebraska Medical Center does not discriminate in its academic, employment or admissions programs, and abides by all federal regulations pertaining to same. Director of Public Affairs Renee Fry, J.D. Senior Associate Director Tom O’Connor Communications Coordinator Karen Burbach contents As I write this in my laboratory on the eighth floor of the Durham Research Center, I have the opportunity to watch the growth of its twin, the latest research facility on campus. toxins slow molecular garbage sweepers The DRC and the new tower together are appropriate symbols of the UNMC research enterprise, growing steadily before our eyes. MERIT scientist unlocks secrets of cilia UNMC research continues to grow during a time of National Institutes of Health (NIH) famine, thanks to the diligence, hard work and world-class excellence of our scientists. This issue highlights some of them and their great work. gold standard care for what price? Study compares top treatments for rheumatoid arthritis Joe Sisson, M.D., is one of five UNMC faculty members to receive the prestigious NIH MERIT award, and the third member of this elite group who is a physician-scientist. This is a well-deserved honor, indeed. Dr. Sisson is an outstanding example of the successful physician-scientist in the 21st century: he is devoted to his patients, nurturing and knowledgeable; and at the same time, is a sophisticated, creative, basic biological scientist – as comfortable in the laboratory as he is in the clinic. Physician researches risks of posttransplant drugs Design Sam Vetter, Daake Design I’m sure you will enjoy this issue as much as I have. I’m proud to be a part of this research family, and look forward to another great year in 2008. University of Nebraska collaboration launches new surgical tools fall 2007 Thomas H. Rosenquist, Ph.D. UNMC Vice Chancellor for Research 14 proteins and tigers and hormones! oh my! Researcher’s quest to purify proteins may impact a $36 billion-a-year industry DNA analyst Mellissa Helligso uses ultraviolet light to reveal evidence of a crime. omaha’s “CSI” unlocks hidden clues DNA lab helps put criminals behind bars under the microscope Researcher collects data on tiniest patients Photography Jim Birrell, Birrell Signature Photography JoAnn Frederick Photography Elizabeth Kumru Bill O’Neill 11 space-age engineering transforms surgery During this century of remarkable advances in biomedical technology, UNMC’s scientists are pioneering work in surgical robotics. One example you’ll read about here is a brilliant collaboration between a surgeon and an engineer whose work will further refine the surgical experience, providing patients speedier recoveries and a reduced rate of infection. Editor Elizabeth Kumru 8 traversing a tightrope of treatment Dr. Sisson has competition at home for the household research award: his spouse is Jennifer Larsen, M.D., also a physician-scientist who is highlighted in this edition. She has an enviable record of accomplishment that includes winning NIH support during this difficult time of limited funding opportunities. Her work is an elegant complement to the overall UNMC organ transplant program, which is one of the biggest, and surely one of the most successful, in the world. As a health sciences center, one of our principal roles in society is basic discovery. But another, equally important role is to harness laboratory discovery and put it into use for the benefit of mankind. Elliott Bedows, Ph.D., and his new protein purification technique illustrates how that process works. 4 on the cover: UNMC and University of Nebraska-Lincoln make inroads in minimally invasive robotic surgery. 20 22 27 A boost to his research came earlier this year when Dr. Sisson, chief of UNMC’s Pulmonary, Critical Care, Sleep and Allergy Section in the Department of Internal Medicine, received the prestigious Method to Extend Research In Time (MERIT) Award from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) to further study the stimulation effects of alcohol on airway clearance. “Dr. Sisson has made considerable progress in unraveling the details by which ethanol impairs ciliary function.” Samir Zakhari, Ph.D. NIAAA Division of Basic Research The MERIT award – which extends Dr. Sisson’s National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grant from 5 years to 9 years – allows him to focus on the science without the need to prepare competitive renewal applications. This increases his total grant award from $2.5 million to nearly $5 million over the 9-year period. toxins slow molecular garbage sweepers “The magnitude and impact of alcohol-related respiratory illnesses has not been widely appreciated, nor extensively studied,” said Samir Zakhari, Ph.D., director, NIAAA Division of Basic Research. “Dr. Sisson has made considerable progress in unraveling the details by which ethanol impairs ciliary function. His research on the effects of cigarette smoking, alone or in combination with alcohol, has shown that acetaldehyde (an alcohol metabolite) is a mediator in the development of lung disease.” MERIT scientist unlocks secrets of cilia by Karen Burbach Each day, tiny garbage sweepers go to work to clear a path in your lungs. But, it also helped the cilia cinematographer catapult his research career. Without fanfare, the workers – hair-like structures inside the human airways – oscillate 5 to 25 cycles per second to sweep the path clean. “Like a speedometer, we could record how fast they moved, but, back then, we knew little about how they were regulated,” Dr. Sisson said. Their round-the-clock diligence keeps pneumonia and other respiratory diseases at bay by clearing the lung of mucus and inhaled particles. Today, the nationally recognized UNMC scientist and his team are unlocking secrets of how cilia function and are exploring the effects alcohol, smoke, dust and viruses have on the tiny hair-like structures. Joe Sisson, M.D., began videotaping this mobilized army of cilia 20 years ago. It was tedious work, pointing his camera at the miniscule, finger-like lining for a rare glimpse of the synchronized movements that thrust garbage out of the lung. fall 2007 “You have to keep your mind open to possible connections because when you connect the dots, that’s when the unexpected happens,” Dr. Sisson says. In studying the stimulation effects of alcohol on cilia, Dr. Sisson and his research team have discovered that chronic alcohol intake impairs the mucous clearance by interrupting enzymes that normally maintain the cilia. As a result, heavy drinkers are more likely to get pneumonia than non-drinkers. Dr. Sisson has always taken things apart. Early on, it was televisions and lawn mowers in his father’s garage. Today, it’s cilia inside his lab at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Dr. Sisson was headed for private practice when Guy Zimmerman, M.D., introduced him to research. The words of the clinician/researcher at the University of Utah, where Dr. Sisson did his fellowship in pulmonary and critical care, still echo in his head: “He looked me in the eye and said ‘you have a chance to discover something no one has ever seen before.’ ” “natura maxime miranda in minimis,” or “nature is greatest in little things” In 1987, after a research fellowship at the NIH, Dr. Sisson and his wife, clinician/researcher Jennifer Larsen, M.D., returned to the Midwest. The Iowa natives chose UNMC because “here we thought we might make a difference,” Dr. Sisson said. And he did after Stephen Rennard, M.D., then chief of pulmonary and critical care, casually said: “You should think of doing something with cilia.” In nature, cilia help earthworms expel nitrogen wastes and enable clams, oysters and mussels to breathe through curtain-like gills covered with cilia. In humans, each airway epithelial cell contains about 200 cilia, which, in a coordinated fashion, creates waves to propel mucus and particles out of the lung, much like an escalator carries people to different floors. There are millions of cilia – Latin for “eyelash” – within the trachea and bronchial tubes. They exist in the ear, eye, brain and spinal cord and also have a reproductive function – they help propel eggs down the fallopian tube. Humans lacking normal cilia function are plagued with respiratory tract infections, have impaired fertility, get recurrent ear infections and have other complications related to dysfunctional cilia motion. Cilia fascinated Dr. Sisson. “Their motion is gorgeous – almost like a ballet – and there was little known about them,” he said. That didn’t change until the early 1990s when Dr. Sisson replaced his video camera with an early version of the SissonAmmons Video Analysis (SAVA) system, which he designed with software engineer Bruce Ammons, Ph.D. “We had to find an automated way to measure the cilia beat frequency UNMC discover of alcohol stimulates the cilia, but long-term, high-dose use results in a loss of responsiveness among the cilia. Once desensitized, or resistant to stimulation, the cilia are unable to accelerate the removal of mucus and particles from the lung during stress, thus increasing the risk of pneumonia or other lung diseases caused by inhalation such as cigarette smoking or exposure to dusts. Dr. Sisson and UNMC’s Todd Wyatt, Ph.D., also are exploring whether cilia can be protected with medication and if the impact of alcohol in the cilia is reversible. “We have some intriguing clues that these defects may be reversible,” Dr. Sisson said. This image shows four intact ciliated tracheal cells stained with color-coded antibodies. The critical cilia regulation enzyme, nitric oxide synthase (green), is located in the basal The team has approached this problem by examining cilia at three different levels. At the highest level, where the most body of each cilium just below the cilia axoneme (red) where the motor enzymes are located that make cilia beat. so it didn’t take minutes to do an experiment and weeks to analyze the data,” Dr. Sisson said. “SAVA let us analyze a day’s worth of data while we had lunch.” The system, now used in more than a dozen labs around the world, enables scientists to record video directly into the computer to analyze cilia motion. Dr. Sisson’s research expanded to include the impact of alcohol on the lung after UNMC professor and internationally known liver expert Mike Sorrell, M.D, inquired about the effects of acetaldehyde – a breakdown product of alcohol – on cilia. As a pulmonologist, Dr. Sisson was intrigued: acetaldehyde also is a byproduct of smoking. “It seemed the lung was potentially slammed in more than one way,” he said. Dr. Sisson already knew that small quantities of smoke slow cilia beating, but now he would compare it to another molecule. “We knew alcoholics have a higher propensity for pneumonia,” he said. “We wanted to connect the dots and see if impaired cilia were part of the problem.” Dr. Sisson was the first to report, 15 years ago, that nitric oxide is a stimulatory regulator of cilia beating. He has applied his nitric oxide interest to the field of alcohol disease and has advanced the study of alcohol effects on airway clearance. When cilia are stimulated by alcohol, their coordinated movements increase – similar to tall grasses blowing in the wind or the human “wave” at an athletic event – and they produce more nitric oxide. Short-term, low-dose use fall 2007 Short-term, low-dose use of alcohol stimulates the cilia, but long-term, high-dose use results in a loss of responsiveness among the cilia. clinically relevant observations can be made, ciliary function is studied in whole animal. At an intermediate level, cilia function of individual airway cells is examined in a tissue culture system where more complex experiments can be conducted. At the most detailed level, ciliary function in isolated cilia, which have been removed from their cell moorings, are studied in a cell-free system. “We have discovered that nitric oxide is located in the cilia basal at all three levels, which means the ciliary control mechanism is intrinsic to the cilium itself,” Dr. Sisson said. His research with nitric oxide also has prompted studies in the pulmonary research group on how mechanical vests, used in the physical therapy treatment of cystic fibrosis, work and whether the vest stimulates nitric oxide production and promotes improved mucus clearance from the lung. Dr. Sisson, who has had continual NIH funding since 1991, credits Dr. Wyatt for lending a whole new dimension to his research. Only a small percentage of investigators annually are selected to receive the prestigious Method to Extend Research in Time (MERIT) Award from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sisson joins a handful of UNMC colleagues who hold the honor: Irving Zucker, Ph.D., (1992), Lynell Klassen, M.D., (2000), Howard Gendelman, M.D., (2001), and Michael Brattain, Ph.D., (2001). “Focusing on the combination of cigarette smoke and alcohol is novel,” said Dr. Wyatt, associate professor in UNMC’s Pulmonary, Critical Care, Sleep & Allergy Section, noting that UNMC, along with Louisiana State University and Emory University, are the only three major alcohol study groups focusing on the lung in the United States. The pair began studying the effects of the two social ills, Dr. Wyatt said, based on observations that more than 95 percent of alcoholics smoke cigarettes and between 30 and 50 percent of all cigarette smokers are problem alcohol users. “So many models of the impact of cigarette smoking on the lung for the past 50 years have focused entirely on the exposure of cigarette smoke and have really ignored alcohol,” Dr. Wyatt said. Researchers know that alcohol alters the critical proteins, or kinases, that regulate cell functions in cilia. But, Drs. Sisson and Wyatt want to know how that occurs, how long it persists if alcohol is removed and the combined impact of smoking and alcohol, on airway kinases. Based on the team’s animal model and tissue culture studies, there is a clear double whammy when alcohol and cigarette smoke are combined, Dr. Wyatt said. In the lung, chronic use of alcohol prevents the stimulation of increased cilia beating and enhanced clearance by blocking the activation of a specific enzyme, cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Cigarette smoking, in combination with alcohol consumption, activates another enzyme, protein kinase C, which directly slows cilia beating. “The combined inhibition of a stimulatory kinase and activation of an inhibitory kinase produces a unique ‘twohit’ disruption of normal cilia beat,” Dr.Wyatt said. As a result, Dr. Wyatt says smoking bans in bars and restaurants are advantageous to public health. “Our research suggests that no amount of the combination of smoke and alcohol can be good for the lung,” he said. Dr. Sisson’s video days may be behind him, but not his enthusiasm to better understand the actions and reactions of cilia. “When you get into interesting science you want to take the engine apart and find out what’s inside the transmission,” he said, setting aside the black marker he’s used to illustrate cilia, his cinematic stars. The promise of basic science, he said, is helping patients with disease prevention and developing better drug therapies. “As a clinician, I want to connect the dots between the basic science and clinical worlds and learn how to detect, prevent and treat cilia disorders in patients who have lung disease, especially those affected by smoking and alcohol.” UNMC discover The drugs by Elizabeth Kumru Gold Standard Care for what price? Study compares top treatments for rheumatoid arthritis The best treatment for the best price. But the answer could save millions of dollars every year for patients and the government. All patients want that, but when rheumatologists have a choice between two effective “gold standard” treatments, one costing 15 times more than the other, the options blur. Dr. O’Dell initially turned to the manufacturers for answers, but pharmaceutical companies have little incentive to compare one treatment to a less expensive therapy. Additionally, the Food and Drug Administration has never required these comparisons. UNMC’s James O’Dell, M.D., and rheumatologists from around the world want to know which medication can provide the best care at the most economical price. Dr. O’Dell, professor of internal medicine and chief of the rheumatology and immunology section, began pondering this question eight years ago. It’s a question the pharmaceutical companies didn’t necessarily want answered. fall 2007 Frustrated, he designed a first-of-its-kind comprehensive $13 million study that will enroll 600 patients from 35 clinics and medical centers in the United States and Canada. The study, funded by Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research, began in July and is expected to take nearly three years to complete. Most rheumatoid arthritis studies have an 80 percent concentration of women, but because many patients will be enrolled through the VA, the study will have equal numbers of men and women. The study, which took four years to develop, is called RACAT (pronounced rocket), an acronym for “Rheumatoid Arthritis: Comparison of Active Therapies.” The random, double-blind study compares two therapies: + A combination of methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine, which costs patients approximately $1,000 a year, to + A combination of methotrexate and etanercept which costs patients approximately $15,000 a year. Methotrexate, an immune suppression drug, has gained popularity among doctors as an initial disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) because of its effectiveness and relatively infrequent side effects. Hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial drug, is considered a DMARD because it can decrease the pain and swelling of arthritis as well as possibly prevent joint damage and reduce the risk of long-term disability. Patients in the study will take one combination of drugs for 24 weeks. If, after that time, there is no improvement, they will be switched to the other combination for 24 weeks. Taking the study a step further, Dr. O’Dell also will determine what role genetics play in the different treatments, or who responds better to which drug combination. “We’ll look for genetic factors and biomarkers that predict disease progression and success or toxicity of the different strategies,” Dr. O’Dell said. “Early treatment is the key to successfully managing this disease,” he said. “Our hope is that one day doctors will be able to prescribe the most effective treatment for their patients based on genetics. That will eliminate a lot of experimenting.” More than 660 million people in the world, including 2 million in the United States, suffer from rheumatoid arthritis. The autoimmune disease causes chronic inflammation of the joints and other areas of the body, and affects people of all ages. Researchers have not been able to determine a cause or a cure for the disease, but treatments are available, with a goal of remission or near remission. Sulfasalazine, an oral medication traditionally used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases, is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis in combination with anti-inflammatory medications. Etanercept is a biologic medication that binds a protein in the circulation and in the joints that causes inflammation before it can act on its natural receptor to “switch on” inflammation. This effectively blocks the tumor necrosis factor inflammation messenger from calling out to the cells of inflammation. Methotrexate alone is an excellent, economical first-line therapy for a significant percentage of rheumatoid arthritis patients, Dr. O’Dell said. However, combination therapy is recommended for those patients who continue to have disease flares, which can result in permanent joint destruction. The group established a serum, plasma, urine and blood bank for investigational purposes. Dr. O’Dell’s original observations of genetic predictors were the first of their kind and have altered the way patients are treated. The current study brings together an impressive coalition of public and private health centers across two In a 1996 study, Dr. O’Dell proved that triple therapy, a combination of three drugs – methotrexate, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine – was 50 percent more effective in treating rheumatoid arthritis than methotrexate alone or the combination of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine. That study was conducted through the Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigational Network (RAIN), a group of rheumatologists and nurse-study coordinators in several states across the country. Dr. O’Dell founded RAIN in 1989; its home base is at UNMC. UNMC discover “This is an exciting, groundbreaking study that will answer important questions about the effective and economical treatments for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.” David Daikh, M.D., Ph.D. University of California-San Francisco countries. In addition to the 10 sites in the RAIN network, Dr. O’Dell recruited 15 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers and 10 Canadian Rheumatology Research Consortium (CRRC) sites. One of those sites, the San Francisco VA Medical Center, is slated to enroll 20 patients, said David Daikh, M.D., Ph.D., chief of rheumatology at the VA center, and associate professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco. “This is an exciting, groundbreaking study that will answer important questions about the effective and economical treatments for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. As we gain more understanding about the disease and more therapies are developed, we can begin to turn our attention to the next big frontier of targeting therapeutics. That’s where the genetic data will be helpful,” he said. The VA and CRRC now spend more than $50 million every year on these expensive therapies and are very interested in the results of this study, Dr. O’Dell said. Traversing a tightrope of treatment by Lisa Spellman “I think clinicians around the world will use this information to make better judgments for their patients who have rheumatoid arthritis,” he said. Rheumatoid arthritis registry fills important niche by Chuck Brown A registry created by Nebraska researchers and containing information about military veterans with rheumatoid arthritis may offer important insights into male rheumatoid arthritis sufferers. “The veterans registry allows researchers to examine specific medical and biological information about hundreds of male rheumatoid arthritis suffers to see what genetic and environmental factors may have played a role in the patients’ disease,” said Ted Mikuls, M.D., an associate professor of rheumatology at UNMC who oversees the registry. Rheumatoid arthritis often affects women between 20 and 50 years of age. Men are usually affected later in life. “While fewer males may suffer from rheumatoid arthritis, they still compose a significant portion of the population with the disease,” said Dr. Mikuls, who also serves as a rheumatologist with the VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System. “Because the veteran population is so overwhelmingly male, we are in a special position to gather information about men suffering from the disease.” 10 fall 2007 Males account for more than 90 percent of the roughly 900 veterans with information in the Veterans Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis registry (VARA ) – making it perhaps the nation’s top source of information about male rheumatoid arthritis sufferers, Dr. Mikuls said. Dr. Mikuls and Amy Canella, M.D., an assistant professor of rheumatology at UNMC who also works at the Omaha VA, started VARA in 2002. VA medical centers in Omaha, Denver, Dallas, Washington, D.C., and Salt Lake City contribute information to the database. More centers are expected to join the registry. Leading rheumatoid arthritis scientists from around the nation, including Peter Gregersen, M.D., of The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y., and James O’Dell, M.D., chief of UNMC’s rheumatology and immunology section, have expressed interest in the data collected in VARA. “You don’t usually find such a well-defined cohort,” said Dr. Gregersen, who has led the world’s largest effort to identify the genes involved in rheumatoid arthritis. Ted Mikuls, M.D. Dr. Gregersen has mined hundreds of millions of genotypes from VARA that he plans to use in his research. Being able to look at such a specified group of rheumatoid arthritis sufferers may offer insight into how genetic and environmental factors play into the cause of rheumatoid arthritis, he said. VARA is a truly unique and powerful resource thanks to the combination of a well defined clinical cohort with radiographic data, serological studies, DNA information and banked biological material, Dr. O’Dell said. “VARA is certain to teach us much about rheumatoid arthritis for years to come,” he said. Kea Huq knew it would be a balancing act after her kidney transplant in 2004. On one hand she felt better than she had in years, on the other she would forever be forced to take powerful medications to keep her body from rejecting the donated organ. One risk she didn’t count on was developing diabetes because of those medications. With more than 97,000 people on the waiting list for an organ transplant, Huq (pronounced ‘Huk’) considered herself lucky to receive a new kidney. UNMC discover 11 “While genetics probably plays a role in the development of diabetes after transplant, immunosuppressant drugs may push individuals at risk over the edge if they can cause insulin resistance, too.” UNMC seeks national recognition as ‘bench to bedside’ leader Kea Huq Jennifer Larsen, M.D. “I was so glad to be alive,” Huq said. But, her happiness would turn into anxiety a year after her transplant when the Douglas County Hospital charge nurse was diagnosed with diabetes. Roughly 25 percent of transplant patients develop diabetes after their life-saving operation. Jennifer Larsen, M.D., associate dean for clinical research at UNMC, is working to prevent this treatment complication. In 2006, Dr. Larsen published a study in the journal “Transplantation” that provides evidence to support her theory that the immunosuppressant drugs tacrolimus and sirolimus, known by the trade names Prograf® and Rapamune®, cause insulin resistance. “It was widely believed that corticosteroids, such as prednisone, one of the most common anti-rejection drugs, was the main cause of insulin resistance and diabetes after a transplant. “Considerable effort was made to find immune suppressant regimens that didn’t require corticosteroids that would still be as effective. Often those regimens included tacrolimus or sirolimus, but post-transplant diabetes wasn’t reduced,” she said. Dr. Larsen began to wonder if these two immunosuppressants could be the culprit and in 2004 began testing her theory in male rats. “After just two weeks of daily injections of either drug, the normal rats began to have elevated blood sugars,” she said. More importantly, Dr. Larsen discovered that treatment with sirolimus resulted in higher blood insulin levels, even more than the tacrolimus. “This is similar to what occurs with insulin resistance that leads to type 2 diabetes,” she said. 12 fall 2007 Now, Dr. Larsen wants to understand how these two important anti-rejection medications cause insulin resistance. patients before and after they receive a kidney, pancreas or islet cell transplant. “If we can discover the mechanism, maybe we can tailor new immune suppressant drugs that are less likely to cause diabetes or develop therapies to prevent diabetes in transplant patients,” she said. Patients who receive a kidney, pancreas or islet cell transplant are screened for elevated glucose levels at every visit – at least four times the first year following their transplant and at least once a year thereafter. Huq, who received her transplant at the Mayo Clinic in Minneapolis, appreciates Dr. Larsen’s commitment to finding a way to prevent diabetes in people who already have gone through so much. Dr. Larsen credits James Lane, M.D., an endocrinologist at UNMC who works closely with the transplant team, with discovering that if transplant patients are going to develop diabetes, they are most likely to develop it in the first year after their transplant. “These anti-rejection medications are so powerful, I wish more doctors would be careful,” Huq said. And so it was for Huq, who began to notice her blood sugar numbers rise within the first few months after her kidney transplant. But without the medication Huq’s body would reject the new organ. While post-transplant diabetes can occur after any transplant, the current numbers are generally lower after a liver or heart transplant than after a kidney transplant, Dr. Larsen said. Many factors contribute to these differences, such as the age at which the individual has the transplant, their individual risk factors for developing diabetes, such as weight and family history, as well as which medications are used, she said. “While genetics probably plays a role in the development of diabetes after transplant, immunosuppressant drugs may push individuals at risk over the edge if they can cause insulin resistance, too,” Dr. Larsen said. “When I first noticed it my blood sugar was 120,” she said. “My doctors suggested I change my diet to try to control it, but it continued to rise.” Normal fasting blood sugar is less than 100. Fasting blood sugars between 100 and 125 are now recognized to represent pre-diabetes, which suggests diabetes could be developing and fasting blood sugars of 126 or greater is the level at which diabetes is diagnosed. When her blood sugar hit 160, Huq sought out a doctor closer to home to help control her blood sugar. Huq is now followed by Dr. Lane. She has her lab work done at UNMC and sent to her doctors at the Mayo Clinic. So far, Huq only has had to take medications to help control her diabetes. And patients who develop insulin resistance and diabetes after transplant seem to require insulin for treatment sooner than individuals who develop diabetes who’ve never had a transplant. While she has not had the easiest time since her transplant, Huq said she would do it all over again if she had to, with one exception. That’s why Dr. Larsen and other diabetes physicians work closely with the transplant team at UNMC to evaluate “I would want to know more about the medications and talk to the doctors about trying to find the best combination so that, hopefully, I wouldn’t develop diabetes,” she said. UNMC is striving to become a national leader in clinical and translational research in the areas of cancer, transplantation, biopreparedness and neurosciences. The academic medical center hopes to secure one of the 60 Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) from the National Institutes of Health. In November, the NU Board of Regents approved the establishment of the Center for Clinical and Translational Research in an attempt to strengthen the pending application. UNMC plans to apply for the CTSA award in October 2008. The comprehensive center will provide an administrative structure, improved training, space and core facilities to support clinical and translational research across all four UNMC campuses. Collaborations with underserved communities also will be developed. The advent of this new award is part of a national movement to create a stronger health care system by transforming clinical and translational research at academic health centers across the country. NIH officials created the awards to increase collaboration between researchers from differing disciplines, making the translation of research from bench to bedside more efficient. Improved interactions between scientists, clinical practitioners, behavioral specialists, biostatisticians, epidemiologists, bioengineers, pharmacologists, medical economists, community members and patients may be key to solving medical mysteries, said Jennifer Larsen, M.D., associate dean for clinical research, UNMC College of Medicine. Dr. Larsen said UNMC hopes to receive a CTSA by the time the award process is finalized in 2012. In preparing to apply for a CTSA, Dr. Larsen’s team has been re-evaluating UNMC’s clinical and translational research enterprise. Some of the new developments out of this process include the initiation of a new research-training track that allows different health care professionals to learn the latest clinical and translational research technology side-byside. Other developments include a universitywide clinical and translational research seminar for both clinicians and basic scientists and exploring new ways that investigators with common research interests can meet and collaborate. “UNMC has many resources in place that make securing a CTSA possible,” Dr. Larsen said, “including new research facilities, multiple areas of established translational research expertise, an electronic medical record and considerable expertise in the areas of health informatics and bioinformatics.” Even so, she said, there is much left to do to improve collaborations across disciplines, as well as with neighboring institutions. UNMC discover 13 Space-age engineering transforms surgery by Chuck Brown Technology that enables robots to explore the rocky and formidable terrain of Mars is being adapted to explore another new frontier – the inner human body. Dr. Farritor – a native of Ravenna, Neb., and a 1992 UNL graduate – had helped make waves around the, well, galaxy for his contributions to the Mars Rovers. UNMC’s Dmitry Oleynikov, M.D., and UNL’s Shane Farritor, Ph.D., met during a spring 2002 research retreat and proposal contest designed by the vice chancellors of the two schools to encourage cross-disciplinary cooperation among scientists from each campus. Before returning to his alma mater in 1998, he worked in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Field and Space Robotics Laboratory and the Unmanned Vehicle Lab at the C.S. Draper Laboratories in Cambridge, Mass. He also studied at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “Number three on the list was miniature surgical robots inside the body,” Dr. Farritor said. “I like to joke with Dmitry 14 fall 2007 Dr. Oleynikov had just been recruited from the University of Washington by UNMC Surgery Department Chairman Byers “Bud” Shaw, M.D., to raise the medical center’s profile in the world of advanced surgical technology. So it seems fate clearly intervened five years ago when a UNMC surgeon introduced himself to a University of Nebraska-Lincoln engineer with ties to NASA, launching a collaboration that is revolutionizing surgery. After their initial meeting, Dr. Oleynikov gave Dr. Farritor a list of five ideas they could explore for their research proposal. Dmitry Oleynikov, M.D. that his other four ideas were horrible – but he was onto something with the robots.” Together, their mini robot project captured the imaginations of the vice chancellors for research and received an award that came with $60,000 in project funding. Shane Farritor, Ph.D. UNMC discover 15 Dr. Farritor displays two of the surgical robots he and Dr. Oleynikov have developed. On the left is a mobile camera robot that can move around inside of a body cavity and provide images to surgeons. The robot on the right is the ceiling pan/tilt robotic camera which provides a bird’s-eye view of the surgical site. Even before coming to UNMC, Dr. Oleynikov was interested in surgical robots. “We realized we had a special opportunity and we were determined to make something happen,” Morien said. At the time, the world’s most advanced robotic surgical solution was Intuitive Surgical’s da Vinci® Surgical System – a large robot that mimics a surgeon’s hand movements during an operation and is able to negate potential hand tremors that can hinder surgery. She recalls one other aspect of the lunch as well. UNMC was the eighth medical center in the country to acquire the da Vinci system – putting UNMC on the map in the area of computer-assisted surgery. While the da Vinci enables more complex procedures to be performed on a minimally invasive approach, it doesn’t remedy some of the major obstacles of laparoscopic surgery, in particular limited range and motion of the scope cameras and lights that enter a patient’s body through a small incision. “The scopes can only move so much because we don’t want to make the incision larger, so it makes it hard to see everything around the area we are operating on,” Dr. Oleynikov said. “I remember picking up the bill,” she joked. Dr. Farritor was as intrigued by the idea of making robots that could navigate the body’s inner organs as he was in designing robots that traveled the surface of Mars. “In reality, the robotic concepts used to get robots to move on Mars or in the body are the same,” Dr. Farritor said. “Both are ‘remote environments’ where the robot is operating in a strange place. “This brings with it a lot of engineering challenges, such as how the robot is controlled, what sensor information is needed and how decisions are made. “We were trying to make a robot that would drive around on the organs while not causing damage,” Dr. Farritor said. “The environment is delicate, soft and slick and you don’t want to get stuck.” As they moved into development, Dr. Farritor observed Dr. Oleynikov performing surgery to get a better understanding of what he was looking for in the robots and what issues surgeons face in their work. The team experienced some challenges in getting the robots to where they could move across certain organs, Morien said. ”Surfaces are different depending on the organ,” Morien said. “The gall bladder is different from the liver, which is different from the bowel. Our robots had to be able to roll on all of them.” Within a year of their Cajun meal, the team had a prototype developed. Drs. Oleynikov and Farritor have since designed a suite of robots, all about the size of a lipstick case. Some robots carry lights, others carry cameras and one is even capable of performing a biopsy. They are all controlled through a computer, meaning surgeons can operate the robots from hundreds of miles away. This aspect made the robots attractive to the U.S. To remedy this, Dr. Oleynikov began thinking small – really small. He envisioned tiny robots the size of a lipstick case that could be placed in a patient’s abdominal cavity and move around in a patient’s body. Armed with cameras, lights and other tools, robots could provide surgeons with a much greater range of operation, he thought. One of hundreds of sketches the team drafted in the development of miniature surgical robots. Traditional scopes, and even those associated with the da Vinci system, require their own incisions. Dr. Oleynikov envisioned robots that would be able to enter and exit the body through incisions made for other instruments – thus reducing the number of cuts and shortening healing time. He envisioned tiny robots the size of a lipstick case that could be placed in a patient’s abdominal cavity and move around in a patient’s body. 16 fall 2007 Drs. Oleynikov and Farritor decided to pursue miniature robots as their research proposal during an idea-filled lunch two months later at a Cajun restaurant in Lincoln, complete with napkin drawings of potential robot models. Marsha Morien, executive director of the University of Nebraska Center for Advanced Surgical Technology, remembers the lunch as an energetic encounter with ideas flowing quickly between the two scientists. UNMC discover 17 The ceiling pan/ tilt robot sits inside a simulated thorax. This camera robot magnetically affixes to the surface of the abdomen to provide the surgeon with a view of the surgical site. The partnership between Drs. Oleynikov and Farritor is an example of a common theme being emphasized at research institutions around the world – collaboration across disciplines. With an increased push toward clinical and translational research, scientists around the world are being asked to look beyond their own fields for collaborative partners. “It really is an equal partnership with each one of us adding vital components to the mix,” Dr. Oleynikov said. “Without one, the other would not succeed.” Dr. Farritor agreed, noting that the timing seemed right. “It works well because he’s a medical guy who knows a little about robots, and I’m a robot guy who now knows a bit about medicine,” Dr. Farritor said. The collaboration between Drs. Oleynikov and Farritor is a perfect example of such cooperation, said Tom Rosenquist, Ph.D., vice chancellor for research at UNMC. “Drs. Oleynikov and Farritor have combined their considerable expertise and produced robots that could “Robots are the future of surgery, I truly believe that. I envision a time when a surgeon’s hands no longer need enter a patient’s body.” Dmitry Oleynikov, M.D. Department of Defense – which has authorized the team to receive grants of about $6 million to advance development of the robots. If a soldier is wounded on the battlefield, theoretically a medic at the site could insert a robot into a patient, allowing a remote surgeon to quickly diagnose a wound – potentially speeding treatment and reducing casualties. NASA also has expressed interest in the robots under the premise that they could be used should a medical emergency occur in space. The robots have proven successful in animal trials – assisting surgeons in the removal of a pig’s gall bladder with no harm to the animal. 18 fall 2007 “The robots performed very well and provided the kind of support we had envisioned they would,” Dr. Oleynikov said. The team is now awaiting approval from UNMC’s Institutional Review Board to begin human trials. If human trials prove successful, Dr. Oleynikov said it’s possible the surgical robots could be on the market as early as next year. To market the robots and other technology developed along the way, Drs. Oleynikov and Farritor have founded Nebraska Surgical Solutions – a start-up company that will let them capitalize on what could be a revolutionary development in the world of surgery. “Robots are the future of surgery, I truly believe that,” Dr. Oleynikov said. “I envision a time when a surgeon’s hands no longer need enter a patient’s body.” lead to a surgical revolution,” Dr. Rosenquist said. “They demonstrate how such collaboration can lead to scenarios where everyone wins.” Their cross disciplinary approach and venture into surgical robots also drew praise from one of the world’s leading surgeons, Richard Satava, M.D., professor in the University of Washington Department of Surgery and founder of the international conference, Medicine Meets Virtual Reality. “Such a revolutionary concept requires just the type of multidisciplinary team with tremendous experience in innovation that has been assembled,” Dr. Satava said. “This not only brings credibility to the project, but also greatly increases the chance of success.” To both men, their work represents a perfect and simple amalgamation of the expertise they bring to the table. Nebraska is NOTEworthy The vision of Dmitry Oleynikov, M.D., of a world where robots replace surgeons’ hands within a patient’s body may already be catching up with reality. A new push in the world of surgery is the development of what is called Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery or NOTES. The idea behind NOTES is for surgeons to enter the body through natural orifices such as the mouth, eliminating external incisions and visible scars for patients. Dr. Oleynikov and Shane Farritor, Ph.D., have developed a special robot that enters a person’s mouth, moves down the esophagus and into the stomach, where it makes a small incision to gain access to the inner body and assist with surgery. The robot then exits the body the same way it entered and the surgeon laproscopically stitches the robot’s incision, leaving no visible scars. The team has begun testing their NOTES robot on animals. “Time will show that using our robots is the best way to do NOTES,” Dr. Farritor said. This is so, Dr. Oleynikov said, because the current method of performing NOTES involves using tools not suited for the job, particularly a camera scope that is actually designed to remove polyps on the colon, not perform surgery. “Surgeons who use our NOTES robots will have the right tool for the job,” Dr. Oleynikov said. UNMC discover 19 Although some of the findings were published in the journal “Biochemistry” between 2004 and 2007, there is more to the story. Proteins and tigers and hormones! Oh, my! The technology ultimately caught the attention of UNeMed, the technology transfer organization for UNMC. The technology was so compelling that it was identified as having commercial potential. It is now being further developed, with several patents pending. The possibilities for Dr. Bedows’ new technique are vast in the recombinant protein purification world, a $36 billiona-year industry. It lowers the cost and cuts the time for purification from days to hours. Part of the cost savings come from eliminating the need for disposal since no toxic chemicals are used. by Vicky Cerino While studying early pregnancy loss, a UNMC scientist discovers a better way to purify proteins To researchers, scientific discoveries are like dangling fresh meat in front of tigers. They are impossible to ignore. Such was the case for Elliott Bedows, Ph.D., and Jason Wilken, Ph.D., whose discovery significantly changed the course of a research project and may ultimately benefit humans and endangered tigers. It also may impact a $36 billion-a-year industry. The project: Advance reproductive biology in humans. The problem: Discover the cause of pregnancy loss within the first three weeks of conception. The approach: Compare the structure-function relationships of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone made in response to human pregnancy, to mCG, the parallel hormone of the Macaque monkey. Conventional wisdom said the two hormones had identical physiological functions. But, Drs. Bedows and Wilken, a graduate student at the time and now a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University School of Medicine, found a difference that challenged scientific literature. To prove their findings, they ran their arduous experiments again and again. 20 fall 2007 In November 2006, Allied Minds, a Boston-area company that invests in successful early stage technology, purchased the license, formed Purtein, LLC, and invested $500,000. James Linder, M.D., president of UNeMed, said the “We wanted to find the difference, so we built new, but related proteins to study,” said Dr. Bedows, associate professor, UNMC School of Allied Health Professions. “It’s a unique concept because most purification schemes work on charge or on an amino acid sequence, or some other basic chemical aspect. Our technique targets the shape of a molecule, which is why it’s such a novel approach,” Dr. Bedows said. “When you introduce a foreign matter, it might work the first time, but after that, the immune system may destroy it. Sterilization is one concern,” Dr. Armstrong said. The team is testing small amounts of tiger hormones on cell cultures in the laboratory and preliminary results show the technology works. By safer, Dr. Bedows was referring to the toxic chemicals that are often used in basic cell biology research. Using these chemicals drives up the cost of the research and ultimately the cost of drug development. The technique did more than purify the targeted protein; it purified every protein they tested with the same general shape. In 2005, Dr. Bedows used the technology to engineer and purify new tiger hormones to stimulate ovulation for in vitro fertilization in order to reproduce endangered tigers. The purified hormones appear to be far superior to hormones currently used from humans, cattle or pigs. Hormones from humans, cattle and pigs can produce an unwanted immune system response in tigers. “We are building new tiger hormones and purifying them in high enough quantities so the zoo can start using tiger hormones for in vitro fertilization and assisted reproduction,” Dr. Bedows said. “What they get is a tiger hormone that is so genetically similar that the tiger recognizes the hormone as its own, thereby avoiding potential side effects.” “We had to figure out how to purify all of these proteins – called recombinant proteins. We developed a technique that’s much faster, cheaper and safer than anything that existed.” Recombinant proteins are natural proteins engineered in a different cell system to replicate large quantities of proteins for use in commercial industry, drug development, research, and in diagnostic applications. But before recombinant proteins are useful, they must be purified. Even before licensing the technology, Dr. Bedows was using it to help the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha. He, Doug Armstrong, D.V.M., associate director for medicine research, and Naida Loskutoff, Ph.D., reproductive physiologist, at the Henry Doorly Zoo, have been collaborating since 1994 on the zoo’s assisted reproduction program to manage the genetic diversity in zoo animals. Dr. Bedows draws blood from a female tiger at the zoo with the help of keeper Hannah Savorelli. venture with Allied Minds is an exciting one. “We see the partnership as a fast, effective way to commercialize this novel technology.” “That’s the beauty of the invention,” said Chris Silva, CEO of Allied Minds and Purtein. “They created a way of purifying proteins in a novel and economical manner that brings down the cost.” “The next step is to produce enough hormones to try it in a tiger,” Dr. Armstrong said. “If it works, we’ll gear up a whole system to produce enough hormones for our zoo, and also share them with others. There are only a couple of places in Europe that have attempted assisted reproduction with tigers. We’ve heard of no one else who has invested effort and resources to produce big cat hormones.” After 30 years in the laboratory, Dr. Bedows was reminded that surprises in basic research are impossible to ignore. “It turns out, much to my chagrin, that the technology to advance our research was more valuable than the research itself – we got more funding for the technique than for the scientific data we produced,” Dr. Bedows said. Dr. Bedows explains his research in a video at www.unmc.edu/discover UNMC discover 21 Omaha’s “CSI” unlocks hidden clues by Tom O’Connor Within the darkened lab, Mellissa Helligso waves the crime scene scope over size 6 floral panties that have been laid flat on the table. She’s looking for semen on yet another sexual assault case. More than 700 similar cases were reported in Omaha last year. Helligso, an analyst with UNMC’s Human DNA Identification Laboratory, knows body fluids glow under the UV light. All except blood. “The evidence doesn’t lie,” Helligso says, turning to look at the mug shots of 24 murderers and rapists who are now behind bars, thanks to evidence found in that very lab. “DNA is foolproof,” she said. Hours earlier, Helligso logged the evidence, wondering if this case will be one of the few that actually goes to trial. Nonetheless, she assigns a three-digit number to track the clothing as it makes its way through the laboratory, which is part of UNMC’s Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory. Omaha’s version of the popular TV show, “CSI,” plays out daily here as police detectives bring manila envelopes, sealed with red evidence tape, into the laboratory. Helligso empties the contents onto a freshly bleached laboratory bench. Then, wearing a white lab coat and sterile gloves, she grabs the crime scene scope. Nearby, colleagues do tissue typing for transplant patients, as well as clinical tests on HIV, tumors, viruses and for paternity. 22 fall 2007 UNMC discover 23 Focused on the clothing, Helligso swabs the area to extract the DNA and runs it through a battery of tests that result in a unique profile, which may, or may not, connect the suspect to the crime. Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is the genetic code of all humans. Found in every cell throughout the body, it determines such human traits as eye and hair color, stature and bone density. No two people – with the exception of identical twins – have the same DNA blueprint. Left at a crime scene, that distinct signature has sent suspects to prison; it also has provided those wrongly accused with a “get out of jail free” card. Within a week, Helligso will complete testing on all the evidence, as well as prepare a report of the forensic findings for police. The UNMC laboratory – one of two academic health science centers in the country to house a forensics lab – also is one of two DNA labs in Nebraska. The other is at the Nebraska State Patrol offices in Lincoln. DNA found at crime scene is matched to a sample from a suspect. No two people – with the exception of identical twins – have the same DNA blueprint. DNA profiles are so unique that odds are greater than 1 in 1 quadrillion that a DNA sample from one person would match another’s. 1in 1,000,000,000,000,000 UNMC established the DNA laboratory with its hospital partner, The Nebraska Medical Center, in 1996 in response to the needs of the Douglas County Attorney’s Office. At the time, DNA forensic analysis was done at a limited number of places around the country. When necessary to make its case, the Douglas County DNA analyst Kaye Shepard, left, logs in evidence brought by Omaha Police Detective Robert Butler and Sergeant Staci Witkowski. Joe Choquette reviews raw DNA data on the genetic analyzer. The analyzer measures the peaks, which are compared against other DNA samples. Attorney’s Office would send DNA evidence to a lab in California, go there to take depositions, then fly the DNA experts to Omaha to testify at the trial. the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors. Dr. Wisecarver estimates that probably 70 percent of the lab’s work today is now involved in forensic testing. “This was very expensive,” said Jim Wisecarver, M.D., Ph.D., professor of pathology and microbiology and director of the Human DNA Identification Laboratory. “We were approached by Jim Jansen (then Douglas County Attorney) and Don Kleine (then chief deputy) about creating our own DNA forensic testing lab at UNMC. It would save Douglas County lots of money, and it would provide attorneys with much easier access to DNA experts.” While it’s an impressive workload, the lab also performs hundreds of tests for patients at The Nebraska Medical Center. Kleine, who is now the Douglas County Attorney, said his office relies on UNMC for help in most of its high-profile murder cases. “The DNA laboratory at UNMC gives us a facility that is recognized by people in the community as the gold standard,” he said. “People view UNMC as a leader in the medical arena. They use the same DNA testing process for people undergoing bone marrow transplants. It lends complete credibility to our DNA evidence. It’s tremendous to have this kind of expertise at the local level.” In addition to its credible reputation, Kleine said UNMC’s DNA lab brings neutrality – just as important in a court of law. “The fact that UNMC is a non-law enforcement agency is critical. They will test DNA for anybody,” he said. “We’re just there to report the facts,” Dr. Wisecarver said. The DNA lab has processed evidence for nearly 800 cases in the past 11 years. In 2000, the lab received forensic accreditation from 24 fall 2007 “Our main focus is still patient care – that’s the mission of the university,” he said. “Our goal with the DNA testing is simply to help out the various law enforcement agencies that come to us.” As its workload has increased, the DNA lab has grown to include two full-time analysts – Joe Choquette and Lloyd Halsell – and two parttimers, Helligso and Kaye Shepard. The lab more than pays for itself, Dr. Wisecarver said, noting the $500 charge for each DNA specimen that is tested. “Unlike health care, where you are working on discounts, forensics pays dollar for dollar. This helps our patients and the citizens of Nebraska.” The Nebraska State Patrol in Lincoln, meanwhile, offers free testing, which has resulted in a nine-month backlog of cases, Helligso said, noting, “police appreciate that we can give them results quickly.” Although “CSI” has given forensic medicine a glamorous image, the majority of cases are more routine and involve requests from the public. “We do receive some odd requests,” Dr. Wisecarver said. “Once we were contacted by an individual who suspected that someone had urinated in his coffee cup, and he wanted us to test for it.” UNMC discover 25 Unmistakable evidence Proving a murder case without a dead body is no small feat. That was the task the Douglas County Attorney’s Office faced earlier this year when a 19-year-old Omaha woman, Jessica O’Grady, went missing May 10, 2006. Police investigators on the case focused their attention on O’Grady’s boyfriend, Christopher Edwards, as the leading suspect. In the course of the investigation, the police searched Edwards’ bedroom and car and found excessive amounts of DNA evidence. O’Grady’s blood was found on a sword recovered from Edwards’ residence as well as on a headboard, mattress and the ceiling of Edwards’ bedroom. The DNA evidence was taken to the UNMC Human DNA Identification Laboratory for processing. “Because they didn’t have a body, the county attorney’s office wanted all the DNA evidence it could possibly find,” said Jim Wisecarver, M.D., Ph.D., lab director. “They wanted to build an ironclad case.” It only takes a small quantity of DNA – between 15 and 20 cells – to establish a profile. “We can make a profile from saliva left on a cigarette butt, a licked envelope or postage stamp, or skin cells left on a firearms cartridge, beverage can or bottle,” he said. English scientist Alec Jeffreys first proposed DNA analysis in 1985. By the late 1980s, it was being performed by law enforcement agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation and by commercial “We can make a profile from saliva left on a cigarette butt, a licked envelope or postage stamp, or skin cells left on a firearms cartridge, beverage can or bottle,” Jim Wisecarver, M.D., Ph.D. “You can’t create DNA. You’re not going to get false results. That’s why it’s so powerful.” In his closing argument at the trial, Kleine held up a sign with a large number containing 18 zeroes. He wanted to make the point that there is no disputing DNA evidence. “There was no question (the blood belonged to O’Grady). The probability that it could have been someone else’s blood was like 1 in a quintillion – 10 to the 18th power. “The other side will always try to attack the credibility of DNA evidence, but UNMC’s lab stands with any in the country. It has the credentials, background and expertise,” Kleine said. “I’ve talked to juries afterwards. They always say they found the DNA evidence to be very credible…they have no issue with it. That speaks volumes.” 26 fall 2007 Each day, the world’s littlest human beings fight for their lives in Neonatal Intensive Care Units, their lungs unable to breathe on their own, their bodies unable to regulate their temperature, their blood pressure fluctuating to life-threatening levels. Sometimes born at less than 2 pounds, these babies require around-theclock attention to survive. A pediatrician with three decades of experience in neonatology and developmental medicine, Howard Needelman, M.D., knows firsthand the obstacles that premature infants may face, both during those initial months of hospitalization and throughout their lifetime. Through the follow-up program, Developmental TIPS (Tracking Infants Progress Statewide), approximately 5,000 children have been assessed for neurodevelopmental disability. The children are assessed through various tools, depending on factors including the extent of their prematurity, complexity of their medical history, and the results of preliminary hearing and vision screenings. The children are followed through age 3. Douglas County Attorney Don Kleine built his case on the DNA evidence, and during the two-week trial, both Dr. Wisecarver and analyst Mellissa Helligso were asked to testify. The DNA evidence was compelling, and Edwards was found guilty of the murder in March, 2007. It was the first time in Nebraska history that a jury had rendered a guilty verdict in a murder trial in which the body had not been found. “Trying someone for murder without a body is a unique situation,” Kleine said. “It doesn’t happen very often. I relied on the DNA evidence. Jim and Mellissa did a great job of explaining what DNA is and the scientific process involved in analyzing DNA. Tracking tiny patients For the past 13 years, a program led by Dr. Needelman and Barbara Jackson, Ph.D., director of Education and Child Development at UNMC’s Munroe-Meyer Institute, has served children who spend at least 48 hours in one of Nebraska’s seven major NICUs. The evidence was unmistakable – all the blood samples belonged to O’Grady, who was a student at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Edwards’ mattress had been turned over when investigators reached the scene. It was covered with a huge pool of dried blood. The bedroom walls had been freshly cleaned, but investigators were still able to retrieve blood samples from the walls. under the microscope “Developmental TIPS is the largest standardized follow-up program of its kind in the country,” Dr. Needelman said. “It ensures that each child by Bill O’Neill is assessed by a team with expertise in early childhood development, which in turn provides the children with the best opportunity for success, especially if early intervention is necessary.” That early intervention usually comes from a school district or educational service unit, and often involves physical, occupational or speech therapy. The intervention also highlights the collaborative nature of the TIPS program. “One key to the TIPS program’s success was the collaboration across entities to establish a standard system of follow-up and one centralized database,” said Dr. Needelman, an assistant professor of pediatrics at UNMC. “The university, the hospitals, the schools, the educational service units, the state of Nebraska – a lot of entities have worked together to ensure this program’s success.” The program’s findings, Dr. Needelman said, are mixed. Although the smallest babies have the highest risk of disabling conditions such as cerebral palsy, mental retardation, lung problems, blindness and others, many of those babies do quite well. The larger babies – traditionally thought to be low-risk because of the relatively few services required in the NICU – also do well, but they ultimately receive early intervention services at a rate five to 10 times greater than the average population. “As a neonatologist, it’s wonderful to know that most kids who come out of the NICU do pretty well, even the most vulnerable, smallest children,” Dr. Needelman said. “That said, I think our research results have shown that all children who are in the NICU – even the babies who are there for a short time – need to be followed closely so that they can be given appropriate attention medically and educationally, to ensure that they reach their full potential.” Funded primarily by the state Department of Education with assistance from the state’s hospitals and the Department of Health and Human Services, Developmental TIPS does not charge families for services. A pilot program, measuring how NICU graduates function through their kindergarten years, is being considered. Members of UNMC’s Human DNA Identification Laboratory team are, from left, Mellissa Helligso, Lloyd Halsell, Dr. Jim Wisecarver, Joe Choquette and Kaye Shepard. laboratories. It consists of comparing selected segments of DNA molecules from different individuals. Because a DNA molecule is made up of billions of segments, only a small portion of an individual’s entire genetic code is analyzed. “Over the years, DNA testing has become much more sophisticated,” Dr. Wisecarver said. “Today, it’s all done via computer. We look for the number of repeating units on the chromosome, and we test 16 different spots (or loci) on the DNA. When you get a match, it’s pretty much a lock.” With many patients, the goal is to get them to function as 19-month old Kylie Gilbert looks for Clifford the Big Red Dog during a Developmental TIPS assessment session that includes her mom, Vicki, Barbara Jackson, Ph.D., and Howard Needelman, M.D. Kylie is one of triplets. UNMC discover 27 Construction on the twin to the Durham Research Center is expected to be completed in early 2009. The 10-level facility will contain 252,179 gross square feet with 98 state-of-the-art laboratories, as well as office space for investigators and laboratory support space. Most of the laboratories will be dedicated to research in the College of Medicine, the Eppley Cancer Center, the College of Pharmacy, and to support operations of the Nebraska Public Health Laboratory and the University of Nebraska Center for Biosecurity. Funding for the $74 million facility comes largely through private support, with legendary Omaha businessman Chuck Durham, president and CEO of Durham Resources, providing the lead gift. discover UNMC University of Nebraska Medical Center 985230 Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska 68198-5230 Address Service Requested 28 fall 2007 Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage Paid Omaha, NE Permit No.454