* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

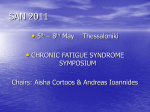

Download Fatigue, Quality of Life, Physical Function and Participation in Social,

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript