* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Joint-Stock Colony

Colony of Virginia wikipedia , lookup

Colonial period of South Carolina wikipedia , lookup

Colonial American bastardy laws wikipedia , lookup

Province of Maryland wikipedia , lookup

Queen Anne's War wikipedia , lookup

Massachusetts Bay Colony wikipedia , lookup

Slavery in the colonial United States wikipedia , lookup

Province of New York wikipedia , lookup

Shipbuilding in the American colonies wikipedia , lookup

Dominion of New England wikipedia , lookup

Colonial American military history wikipedia , lookup

Province of Massachusetts Bay wikipedia , lookup

Cuisine of the Thirteen Colonies wikipedia , lookup

English overseas possessions in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms wikipedia , lookup

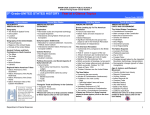

Summary and Conceptual Overview of Colonial Society Joint-Stock Colony: Jamestown, Massachusetts Bay: founded and governed by a corporation under a charter. Proprietary Colony: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, the Carolinas, Georgia: founded and governed by a single person or family, or by a group of proprietors, independent of the crown. Royal Colony: Virginia (1624), all colonies by 1770: governed by royal appointees. Because most of the population was comprised of newcomers, the social structure of the English colonies, at first glance, looked like that of the mother country. The hierarchy that symbolized the class system in England was transplanted, as “lesser” deferred to their “betters.” A free-holder deferred to a planter and a servant deferred to a free-holder. One fundamental difference did exist, however. The colonies had greater social mobility. Many of the first landowners of Virginia had died or returned to England. The next wave of settlers was comprised of men of lesser means, having only one or two servants or no servants at all. They succeeded or failed by their own labors. The turmoil seen in Bacon’s Rebellion or others of which we will speak resulted from the fact that those who had made their own success refused to be governed by cliques or entrenched elites. By the early 1700s, a somewhat more fixed social structure had developed, particularly in Virginia and South Carolina, at least at the upper end of society. Success brought more land and more slaves. Large planters formed a “gentry,” an aristocratic, well-educated, and refined elite who fancied themselves English country gentlemen. Wealthy merchants in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and eastern Maryland combined land-holding and business acumen to enter the upper class. But points north and east tended to be more middle class until later in the century when further urbanization had taken effect. Along the frontier, the Appalachian Backcountry, life remained rustic and brutish for most of the colonial period. It is essential to note in all this, however, that a person could quickly move up or down the social ladder as his fortunes rose or fell in the fluid American economy. New England was characterized by family farms on which all toiled. Slaves, composed mostly of Creoles from the West Indies, worked as household servants and field hands. The region’s rocky soil kept farms small, except along the Connecticut River. Slavery was not so important that it kept New Englanders from abolishing it after moral questions were raised during the Revolution. Looking at the colonial countryside, one would see a tremendous difference in how land was organized and distributed as he traveled from north to south. Part of this was because of geography, part to custom, and part to the local economies. The New England town looked like a town in feudal England—but without a manor lord! Land was distributed based on status--religious or political--and one’s ability to cultivate it. Only those who agreed to the town covenant, and were admitted by existing members could get land. Townsmen had power over whom they would admit and how many. Lands that were developed were parceled out to each man as tiny house-lots, with additional strips of arable meadow and woodland scattered around the village. All lands not parceled were held in common. The whole community used the “common lands” or “commons” for grazing livestock. As population grew, private property rights expanded. By the early 1700s, with town lands already distributed, the second or third generations often had to move away to find opportunity. Thus, migration within and between colonies was common. The economy and land distribution structure in the Chesapeake and points south differed greatly from New England. First, southern colonies were built around single staple crops: either tobacco, rice, or sugar. Growing tobacco was labor intensive as it was planted as seedlings and had to be staked; fields had to be hoed and fertilized; plants topped, etc. Rice cultivation was not only laborintensive, but was also outside of the English experience and so needed workers not only for the labor, but also for their expertise to grow it. Thus, Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas adopted slavery. The plantation’s other distinguishing mark was its social order. In theory, the planters’ rule was complete. From his Great House, he looked out upon trades-shops, barns, sheds, cabins, and other outbuildings that were known as “dependencies.” But his authority radiated beyond the estate to statehouses, courtrooms, counting houses, churches, colleges, taverns, and the like. A plantation economy has certain characteristics: •geography – numerous navigable rivers •manorial tradition of self-sufficient communities •few towns •social distance Political-Economy after the Restoration One of the first acts of King Charles II upon Restoration was to find ways the colonies could more significantly benefit the mother country. The last half of the 1600s saw significant expansion of the colonial economy. Not only did the Chesapeake find its staple cash crop—tobacco—but it also found a stable labor source in black slaves. New England developed as a merchant sea power. Finally, with the taking of New Netherland and creation of proprietary colonies in the mid-Atlantic and South, all colonies, save Georgia, were established by 1700 and about 250,000 people resided in the colonies. Moreover, the idea of controlling the colonial economy had developed into a full-fledged policy: mercantilism. England established its empire to produce the goods needed to make it “self-sufficient,” making the country richer and more powerful. It believed the colonies should provide it with raw resources and with a market for English manufactured goods. Mercantilism Flowchart Wealth = power Gain wealth through trade/commerce Improve “balance of trade” Increase exports and decrease imports Create colonies Control the colonial economy Navigation Acts Parliament passed laws implementing a regulatory system under the Navigation Acts of 1651. This law required that all goods imported into England or the colonies arrive on English ships and that at least half the crew be English. Charles II expanded the law creating a list of enumerated goods, such as tobacco, sugar, indigo, and ginger, that could not be shipped outside of an English-English colony trade system. It added more enumerated goods to the list through the early 1700s . Colonials frequently ignored the laws, smuggling goods from the West Indian holdings of Spain and France. Though many historians paint them negatively, the Navigation Acts helped bring stability to the economy. Unstable markets and a chronic money shortage caused cycles of boom and bust. Crops and ships were at the mercy of weather. In the West Indies, sugar crops could be destroyed by ocean storms; blights and droughts ruined crops on the mainland. Overproduction was a problem. Just as the laws created a market for British goods in America, they ensured a market for colonial products in the mother country. Boom and Bust Cycle: The South Sea Bubble The Glorious Revolution and its Effects on the Colonies Between 1675 and 1689, a power struggle developed between colonies and mother country, as well as between the powerful and powerless within colonies. Five rebellions occurred, involving each of the four colonial regions. Each of the rebellions had causes particular to their colony, but they all reflected a struggle to answer the question: “Who’s in charge.” We have looked at Bacon’s Rebellion already. Other challenges to the governing authority occurred in North Carolina, Maryland, New York, and New England. In North Carolina, John Culpeper led a gang of farmers in trying to stop government officials from collecting tariffs. In 1677, colonial leaders who had been losing money tried to end smuggling of tobacco and to force payment of tariffs. What Culpeper’s Rebellion lacks in altruism it makes up for in confusion. It was really a conflict between several factions all fighting each other. Culpeper and his men seized the government to stop collection of taxes, jailed the acting governor, and petitioned England for support. Culpeper governed for two years in relative calm. By 1680, the rebellion was over, the proprietors were back in control, and settlers went back to their business of defying authority. Even as New Englanders fought King Philip’s War against the Indians, Britain undertook to enforce the Navigation Acts which hitherto had not been enforced in New England. A study by the Lords of Trade suggested that Massachusetts was invading the king’s prerogatives. Conditions between crown and colony worsened until James, Duke of York, had the Lords of Trade revoke the Massachusetts Bay Company’s charter. When Charles II died soon thereafter and since he left no legitimate heir James II came to the throne. King James II moved quickly to re-establish the power of the monarchy in England and in the colonies. To stifle the independent thoughts of Massachusetts, James created the Dominion of New England, to unite and govern the entire region under his absolute authority. The move made sense administratively and it benefitted Britain’ mercantilist objectives. But important differences existed among the colonies. Each had developed distinct political and social cultures. New York had a diverse polity and a social and economic structure that borrowed heavily from the European manorial model. Rhode Island existed as a counterpoint to strict Puritan authority. Connecticut and New Hampshire were tiny. Massachusetts had been founded by two groups who had expressly rejected the kind of royal authority James was imposing on them. Most troubling for citizens of Massachusetts was the plan to establish the authority of the Church of England. When a prominent Puritan minister preached against the new regime, he was arrested and denied a writ of habeas corpus. When challenged on it, the Governor responded, “The scabbard of an English redcoat shall quickly signify as much as a justice of the peace!” Rock-a-bye Baby, on the treetop, When the wind blows the cradle will rock, When the bough breaks the cradle will fall, And down will come baby, cradle and all. James II took the throne in 1675. An avowed Catholic, he exploited his royal prerogatives to enhance Catholic influence in government. England’s political factions to develop into two political parties: Tories (supporters of the King) and Whigs (supporters of Parliament). When James remarried, a French Catholic woman who was “with child,” his opponents in Parliament saw a future of bloody religious conflict. The Whigs rebelled with the help of William of Orange, the husband of James II’s daughter, Mary. James II fled to France and the bloodless Glorious Revolution of 1688 ended. William became King William III and his wife Queen Mary II. The Glorious Revolution bred conflicts in Maryland (Protestant Association) and New York (Leisler’s Rebellion). Leisler’s, Bacon’s, and Culpeper’s Rebellions, and the Protestant Association exposed a deep rift between those in power and those out of power, between economic and/or social ruling elites and the populace. Each colony had to accommodate the rights and interests of the many as well as the few if it was going to survive and prosper. Wars for Empire and their Effects on the Colonies The regime of William and Mary precipitated a series of conflicts with France over control of global empires: King William’s War; Queen Anne’s War; and King George’s War. The wars left Britain deep in debt, causing Prime Minister Robert Walpole to look for ways to cut spending. In 1723, he created the policy of Salutary Neglect, relaxing enforcement of the Navigation Acts and letting the colonial economy run basically unregulated. The loosening of English oversight had broader effects on the colonies. The colonies grew closer together and developed a sense of identity different from Britain. During the brief time of unsupervised growth, the colonies witnessed the Great Awakening and the Enlightenment. When it was abruptly ended, it caused a groundswell of opposition that grew into an independence movement. The Great Awakening In 1734-1735, Jonathan Edwards, a Congregationalist minister from western Massachusetts, began rekindling the spirit of piety to remake America as a “City upon a Hill”. The movement occurred on the extremities of the colony first because, as a Baptist minister observed, frontiersmen were like “A Gang of frantic lunatics broke out of Bedlam.” Jonathan Edwards The Great Awakening affected colonial society in several ways. First, the sects established colleges, such as Presbyterian College of New Jersey (Princeton, 1746); and Baptist College of Rhode Island (Brown, 1764). Secondly, territorial boundaries between churches broke down. Itinerant preachers spread sects across borders, helping to create a national religious culture. Thirdly, religion became increasingly an individual choice. Finally, the rise of individual conscience fostered the breakdown of the “state church.” Religious libertarians began to push for freedom of conscience, which became a rallying cry after the revolution. The Enlightenment The Enlightenment, symbolized by Isaac Newton and John Locke, was limited to the upper and the educated middle classes. Because the upper class were powerful, it is still significant. It reached its peak in America in the 1740s with the creation of the American Philosophical Society, and the rise to prominence of its principal founder, Benjamin Franklin. Perhaps the smartest man in the colonies and certainly the most famous, Franklin embodied the Enlightenment in America as a man of science and letters, and as a deist. Franklin was born in Boston in 1706. Born in 1706, he led the colonies in the French and Indian War, American Revolution, Confederation Era, and in creating the U.S. Constitution. He died in 1790. The Last War for an American Empire In the 1750s, France and England disputed who controlled the land in the Ohio Valley. In 1753, Virginia’s Governor sent an expedition led by George Washington to demand a French withdrawal. The French refused. Washington’s troops fought French and Indian forces near Fort Duquesne. The skirmishes developed into the last French-English global war for empire, the Seven Years’ War. (French and Indian War) In 1754, Ben Franklin called for each of the colonies to send delegates to attend the Albany Congress. Its main purpose was to negotiate an alliance with the Iroquois against the French and their Huron allies in the rising conflict. The Iroquois were the strongest of the inland tribal groups, centered in upstate New York. The alliance held for most of war. The Six NationsIroquois Confederacy At Albany, Ben Franklin devised the Albany Plan of Union to enable the colonies to protect themselves. Franklin called for the creation of a governing council for all the colonies. Some historians have suggested that the Iroquois Confederacy was a model for the U.S. system under the Articles of Confederation—an alliance of sovereign states affiliated for their defense. An actual connection between Franklin’s Plan and the Confederacy is less clear. Franklin’s Plan was not an independence movement; it intended only to bring the colonies closer together. Some colonies thought it was a good idea, but it did not come to pass because most colonies did not want to give up any power to another layer of government. In September 1759 came the death blow for the French. Gen. James Wolfe led a British force against the Marquis de Montcalm at Quebec. Both commanders were killed in the British victory in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. The Treaty of Paris (1763) ended the war. France gave up all claims to North America, ceding land east of the Mississippi River to Britain and west of it to Spain. The Death of General James Wolfe, by Benjamin West (1769). The land between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River posed an opportunity and a problem for Britain. Each new incursion by colonials resulted in war with the Indians. So King George III banned colonists from entering the region. The Proclamation of 1763 banned all settlement west of the continental divide in the Appalachians. The Proclamation of 1763 brought a formal end to the era of Salutary Neglect.