* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download VU1 Electricity 2009

Negative resistance wikipedia , lookup

Electric battery wikipedia , lookup

Operational amplifier wikipedia , lookup

Nanogenerator wikipedia , lookup

Nanofluidic circuitry wikipedia , lookup

Electric charge wikipedia , lookup

Power electronics wikipedia , lookup

Power MOSFET wikipedia , lookup

Resistive opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Rechargeable battery wikipedia , lookup

Current source wikipedia , lookup

Switched-mode power supply wikipedia , lookup

Opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Surge protector wikipedia , lookup

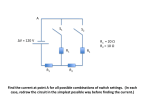

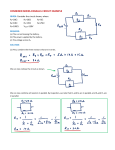

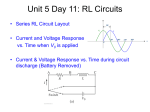

VCE Physics Unit 1 ELECTRICITY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Unit Outline Apply the concepts of Charge (Q), Electric Current (I), Potential Difference (V), Energy (E) and Power (P), in electric circuits. Analyse electrical circuits using the relationships I = Q/t, V = E/Q, P = EIt = VI, E = VIt. Model Resistance in Series and Parallel using:, Potential Difference versus Current (V-I) Graphs Resistance as the Potential Difference to Current ratio, including V/I = R = constant for ohmic devices. Equivalent effective resistance in arrangements in: series: RT = R1 + R2 + R3 + ….. parallel: 1/RT = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + ….. Model simple electrical circuits such as car and household AC electrical systems as simple direct current (DC) circuits. Model household electricity connections as a simple circuit comprising fuses, switches, circuit breakers, loads and earth. Identify causes, effects and treatment of electric shock in homes and relate these to approximate danger thresholds for current and time. Investigate practically the operation of simple circuits containing resistors, including variable resistors, diodes and other nonohmic devices. Convert energy values to kilowatt-hour (kWh) Identify and apply safe and responsible when conducting investigations involving electrical equipment and power supplies. Chapter 1 The Basics 1.0 Electric Charge Atoms consist of a nucleus, containing protons and neutrons, with electrons circulating around it. Electric Charge is a property of some atomic particles. Which ones ? Protons and Electrons. These two particles carry an The UNIT of equal and opposite electric Electric Charge charge. Protons carry a charge of is the This charge is the smallest +1.6 x 10-19 Coulombs COULOMB, known amount of charge that Electrons carry a charge of Symbol (C). exists independently. – 1.6 x 10-19 Coulombs This charge is called the If each electron (or proton) carries such a small “ELEMENTARY CHARGE” charge, a large number would be needed to The charge carried by the make up 1 Coulomb of charge. Proton is DEFINED to be POSITIVE. The charge carried by the Electron is DEFINED to be NEGATIVE. Charge 1. How many electrons in 1 coulomb of charge ? 1 electron carries 1.6 x 10-19 C So 1 Coulomb of charge will have 1/(1.6 x 10-19) electrons = 6.25 x 1018 electrons 2. How many electrons in 7.5 C of charge ? 1C has 6.25 x 1018 electrons so 7.5 C will have 7.5 x 6.25 x 1018 = 4.69 x 1019 electrons 1.2 Electric Current When electric charges are made to move or flow an ELECTRIC CURRENT (Symbol I) is said to exist. The SIZE of the Current depends on the number of Coulombs of Charge passing a given point in a given Time. The Unit of Current is the Ampere often shortened to Amp (Symbol A) Mathematically: I = Q/t Where: I = Current in Amps Q = Charge in Coulombs t = Time is Seconds Electric current has the property of starting immediately a circuit is complete and stopping immediately a circuit is broken. Once the current is flowing it stays the same all around the circuit. 1 Coulomb passing this point in 1 second = 1 amp of current Current flowing along wire So, in 1 second 6.25 x 1018 electrons pass this point Current 3. Calculate the current flowing if 3.57 Coulomb of charge passes a point in 1.25 sec. I = Q/t = 3.57/1.25 = 2.86 Amp 4. If 5.62 A of current flows through a wire in 0.68 sec. (a) How much charge has been moved ? I = Q/t Q = It = (5.62)(0.68) = 3.82 C (b) How many electrons were needed to transport the charge in (a) ? If 1 C of charge is carried by a total of 6.25 x 1018 electrons, then 3.82 C is carried by (3.82)( 6.25 x 1018) = 2.39 x 1019 electrons 5. If a current of 125 A resulted from the movement of 225 C of charge, for how long did the current flow ? I = Q/t t = Q/I = 225/125 = 1.8 sec 1.3 Conventional versus Electron Current In Direct Current (DC) electric circuits, the current always flows in one direction. On circuit diagrams, it is ALWAYS shown as flowing from the positive to negative terminal of the power source. BUT, we know that a current is a stream of electrons (negative particles), which must travel in the other direction. What’s going on ? It is a quirk of history that the current direction is shown this way. Electric currents were discovered before the electron. It was thought that the charge carriers were positive and the current must flow this way, Never shown on circuit diagrams This means the current carriers must be positively charged because they will be repelled (like charges repel) from the positive terminal, and attracted (unlike charges attract) to the negative terminal. Protons are the Positive particles. Wire connected to a Battery Electron Conventional Current Current Always shown on circuit diagrams Conventional vs Electron Current 6. Currents shown on circuit diagrams; A: are from the negative to the positive terminal of the power supply and are called electron currents B: are from the positive to the negative terminal of the power supply and are called conventional currents C: are from the positive to the negative terminal of the power supply and are called electron currents D: are from the negative to the positive terminal of the power supply and are called conventional currents 1.4 Potential Difference For a current to flow around a circuit a “driving force” is needed. This driving force is the difference in VOLTAGE between the start and the end of the circuit. The larger the current you want the greater the Small Drop = Potential Difference (Voltage Difference) you require. Low Pressure Potential Difference (P.D.) is best understood Low output using the water analogy: = low A short drop between storage and tap gives current low water pressure = a low P.D. Large Drop = High Low output from the tap = low current. Pressure SO A SMALL P.D. CAN ONLY DRIVE A SMALL CURRENT. A large drop between storage and tap gives high pressure = Large P.D. High output at the tap = high current High output SO A LARGE P.D. CAN DRIVE A LARGE = High CURRENT. current Strictly, Potential Difference is DEFINED as a measure of the energy given to the charge carriers (the electrons) for them to complete their job, that is, to travel once around the circuit. 1.5 Potential Difference (2) Where: Mathematically: V = E/Q V = P.D. measured in Volts (V) E = Electrical Potential Energy in Joules (J) Q = Electrical Charge in Coulombs (C) This means that by passing through a P.D. of 1 Volt, 1 Coulomb of charge picks up 1 J of energy, or more simply 1 V = 1 JC-1 In this case, each coulomb passing through the battery will pick up 12 J of energy. (The energy is used up in lighting the globe) Answer: 24 J The Battery P.D. is now increased to 24 V. How many Joules of energy will each coulomb now pick up ? There are many terms used in texts to describe Voltage, some of these include Potential, Potential Difference, Potential Drop, Voltage Drop, Voltage Difference At this stage of your studies you can take them all to mean the same thing. The preferred term for the VCAA examiners in Potential Difference One further voltage, EMF (Electro Motive Force), while still measured in volts, is slightly different and cannot be grouped with the other terms. Voltage 7. One coulomb of charge passing through a battery picks up 15 J of energy. What Potential Difference did the charge pass through ? V = E/Q = 15/1 = 15 V 8. An external circuit is connected to a 24 V battery. If 6.5 C of charge passes through the battery. (a) How much energy does each coulomb of charge pick up in passing through the battery ? Each Coulomb will pick up 24 J of energy in passing through the battery (b) How much energy (in total) has the battery supplied to the charge passing through it V = E/Q E = VQ = (24)(6.5) = 156 J 1.6 Electrical Energy The Charge Carriers in a circuit obtain their Mathematically energy from a power source or power supply. E = VQ The amount of energy (E) the charge carriers and since Q = It pick up depends upon the size of the voltage Substituting we get E = VIt difference through which they are forced to Where: travel. E = Electrical Energy (J) Since energy transferred = work done, another V = Voltage (V) way of defining electrical energy (E) is by the Q = Charge (C) work done on the charge (Q) in passing I = Current (A) through a Voltage (V) t = Time (s) An external wire connected to a battery will have electrons flowing through it as shown. In completing the circuit inside the battery, the electrons need to flow from the positive to the Electron negative terminal. Current They will not do this willingly and must be forced through the battery. The work done on the electrons increases their electrical energy and gives them enough energy to do another trip around the external circuit. Electrical Energy 9. A current of 4.2 A is being driven around a circuit by a Potential Difference of 87 V. If the circuit is allowed to operate for 36 s, how much energy has been transferred to the charge carriers ? E = VIt = (87)(4.2)(36) = 1.32 x 104 J 10. A total of 1.2 x 103 J of electrical energy has been transferred to the charge carriers in a circuit driven by a 48V battery. If the circuit is switched on for 12 minutes, how many mA (milliamp) of current will have flowed during this time ? E = VIt I = E/Vt = (1.2 x 103)/[(48)(12 x 60)] = 0.035 A = 35 mA 11. A circuit is switched on for 6.5 minutes in that time 3.5 x 104 J of energy has been transferred to the charge carriers. If the current flowing was 11.3 amps, calculate the Potential Difference of the power supply driving that current. E = VIt V = E/It = (3.5 x 104)/[(11.3)(6.5 x 60)] = 7.9 V 1.7 Electrical Energy (2) The energy picked up by the charge carriers is used up in “driving” whatever device is connected to the external circuit. Here we have an incandescent light globe as part of a circuit. U joules of electrical energy transferred to Heat and Light Q coulombs of electricity carrying U joules of energy enter here Q coulombs of electricity leave here Current flowing along wire Charges have High Energy here Voltage Drop = V volts Charges have low energy here 1.8 Electric Power Electric Power is DEFINED as the Time Rate Of Energy Transfer or the Time Rate Of Doing Work. Mathematically: P = E/t And since E = VIt Substituting we get P = VI Where P = Power (in Watts, W) E = Electrical Energy (J) V = Voltage (V) I = Current (A) t = Time (s) Using Ohm’s Law (See Chapter 2.) The Power formula can be rewritten as: P = VI = I2R = V2/R Electrical Power 12. Calculate the power consumed by an electric drill operating at 240 V and 7.5 A. P = VI = (240)(7.5) = 1800 W 13. An electric oven consumes 1.5 x 107 J of energy while cooking a roast. If the roast took 2 hours to cook, at what power is the oven operating (quote your answer in kW) ? P = E/t = (1.5 x 107)/ (2 x 60 x 60) = 2.1 x 103 W = 2.1 kW 14. An electric kettle is rated at 3000 W. It is fitted with a 15 Amp safety switch. If it is connected to a 240 V supply will the safety “trip” (switch off) ? Back up your answer with a calculation. No; P = VI I = P/V = 3000/240 = 12.5 A less than the 15 A safety switch rating 15. The kettle mentioned in Q 14 is taken on a world trip by its owner. In America (where the mains supply operates at 110V) he plugs it into a wall socket. Will the safety switch trip now ? Back up your answer with a calculation. Yes; P = VI I = P/V = 3000/110 = 27.3 A greater than safety switch rating 1.9 Common Electrical Symbols Single Cell Battery A.C. Power Supply Earth or Ground Switch Crossed Wires - Joined Crossed Wire not Joined Fixed Resistor Variable Resistor Diode Capacitor V A G Voltmeter Ammeter Galvanometer Globe LED Electrical Components 16. Identify the numbered components in the circuits below 1 (a) (b) A V 3 2 4 2 1 3 5 6 4 5 G (a) 1 = Variable Resistor, 2 = AC Supply, 3 = Ammeter, 4 = Lamp, 5 = Earth, 6 = Switch (b) 1 = Voltmeter, 2 = Battery, 3 = Capacitor, 4 = Galvanometer, 5 = Fixed Resistor 1.10 Series and Parallel Electrical components can only be connected together in one of two ways: Series – where components are connected end to end Series Parallel Parallel - where components are connected side by side. 1.11 A Typical Electric Circuit An electric circuit contains a number of components, typically: •A Power Supply •Connecting Wires •Resistive Elements •Meters This power supply is a D.C. Supply (a Battery), and it drives the current in one direction only. Connecting wires are drawn as straight lines with right angle bends. They are always regarded as pure conductors having no resistance. Circuit diagrams are usually drawn in an organized manner with connecting wires drawn as straight lines and the whole diagram generally square or rectangular in shape. The Voltmeter measures the This represents the part of the voltage drop across the circuit where electrical energy resistive element. It is connected in parallel is consumed. The resistive element could be It has a very high internal resistance which diverts very a light globe or heater or a little current from the main radio or a television. circuit. Resistive Element V Connecting Wires Power Supply A The Ammeter measures current flow in the main circuit. It is connected in series It has virtually no internal resistance so as not to interfere with the current in the main circuit Meters 17. A Galvanometer (which is a very sensitive ammeter) when included in a circuit should be connected: A: In parallel B: Across the power supply C: In series D: Any way around, it doesn’t matter 18. In ideal circuits the wires used to connect the circuit components together have: A: No resistance B: A small amount of resistance C: A large amount of resistance D: An infinite amount of resistance. 19. Voltmeters and Ammeters differ because: A: Voltmeters have low internal resistance and are connected in series while Ammeters have high internal resistance and are connected in parallel. B: Voltmeters have high internal resistance and are connected in parallel while Ammeters have low internal resistance and are connected in series. C: Voltmeters have low internal resistance and are connected in series while Ammeters have high internal resistance and are connected in parallel. D: Voltmeters have high internal resistance and are connected in series while Ammeters also have high internal resistance and are also connected in series Chapter 2 Resistance 2.0 Resistance All materials fall into one of three categories as far as their electrical conductivity is concerned. ALL materials exhibit some opposition to currents They are either : flowing through them. 1. Conductors 2. Semiconductors, or Conductors show just a small amount of opposition. Semiconductors show medium to high opposition. 3. Insulators Insulators show very high to extreme opposition. This opposition is called ELECTRICAL RESISTANCE. The amount of resistance depends on a number of factors: 1. The length of the material. 2. The cross sectional area of the material. 3. The nature of the material, measured by Resistivity Length = L A1 Wire 1 Mathematically: R = ρL/A Where R = Resistance in Ohms (Ω) ρ = Resistivity in Ohm.Metres (Ω.m) L = Length in Metres (m) A = Cross Sectional Area in (m2) A2 Wire 2 Wires 1 & 2 are made from the same material (ρ is the same for each), and are the same length (L is also the same). Wire 1 has twice the cross sectional area of Wire 2. Wire 1 has ½ the resistance of Wire 2 Resistance 20. Nichrome wire is sometimes used to make the heating elements in electric kettles. It has a resistivity of 6.8 x 103 Ω.m. Calculate the resistance of a piece of nichrome wire of length 1.2 m and cross sectional area 2 x 10-4 m2 R = ρL/A = (6.8 x 103)(1.2)/(2.0 x 10-4) = 4.1 x 107 Ω = 41 MΩ 21. Two pieces of wire are made of the same material and are of the same cross sectional area. Wire 1 is 3 times as long as wire 2. A: Wire 1 has 3 times the resistance of Wire 2 B: Wire 2 has 2/3 the resistance of Wire 1 C: Wire 1 has 1/3 the resistance of Wire 2 D: Wire 1 has 6 times the resistance of Wire 2 2.1 Resistors Resistors are conductors whose resistance to current flow has been increased. They are useful tools for demonstrating the properties of Electric Circuits. Understanding how these circuits work is an important life skill you all need to develop. Resistor is a generic term representing a whole family of conductors such as toaster elements, light bulb filaments, bar radiators and kettle elements. They are represented on circuit diagrams as either, 1kΩ or 1kΩ There are only two ways to join resistors together IN SERIES: The resistors are connected end to end with only one path for the current to flow. The more resistors the greater the overall resistance IN PARALLEL The resistors are connected side by side with more than one path for the current to flow. The more resistors the lower the overall resistance 2.2 Resistors in Series Connected end to end, this combination of resistors gives only 1 path for current flow. I1 I2 I3 R1 RRT2 R3 V1 V2 V3 I VS The TOTAL RESISTANCE (RT) of this combination equals the sum of resistances Thus, RT = R1 + R2 + R3 In other words, the 3 resistors can be replaced in the circuit with a single resistor of size RT Because there is only 1 path for the current to flow, the current must be the same everywhere. The current drawn from the power supply (I) is equal to the currents through the resistors. Thus I = I1 = I2 = I3 The sum of the Potential Differences across the resistors is equal to the Potential Difference of the supply Thus VS = V1 + V2 + V3 Resistors in Series 24 Ω 21.(a) Calculate the equivalent resistance that could replace the resistors in the circuit. 11 15 Ω 11 Ω 12 2.9 1.8 v3 I = 0.12 A 6.0 In series resistances add. RT = R1 + R2 + R3 = 24 + 15 + 11 = 50 Ω (b) Determine the value of V3 In a series circuit VS = V1 + V2 + V3 V3 = VS – (V1 + V2) = 6.0 – (2.9 + 1.8) = 1.3 V (c) Determine the values of I1 and I2 In a series circuit, current is the same everywhere so I1 = I2 = I = 0.12 A 2.3 Resistors in Parallel When connected side by side, this combination of resistors (called a parallel network) gives many paths for current flow. The TOTAL RESISTANCE (RT) is calculated from: R1 I1 1/RT = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3. V1 In other words the three resistors can be replaced by a single resistor of value RT. I2 RRT2 The physical effect of this formula is that the V2 value of RT is always less than the lowest value resistor in the parallel network. I3 R3 The current has many paths to travel and the V3 total current drawn from the supply (I) is the sum of the currents in each arm of the network. I Thus I = I1 + I2 + I3 VS Each arm of the parallel network gets the full supply Potential Difference. Thus VS = V1 = V2 = V3 Resistors in Parallel I = 12 mA 1 kΩ 22. (a) What single resistor could be used to replace the 3 resistors in the circuit ? I1 v3 3 kΩ 1/RE = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3 = 1/1000 + 1/3000 + 1/12000 RE = 706 Ω (b) Determine the values of V1, V2, and V3 In a parallel network VS = V1 = V2 = V3 = 12 V (c) Determine the value of I1 In a parallel network I = I1 + I2 + I3 I1 = 17 – (12 + 1) = 4 mA I = 1.0 mA v2 12 kΩ v1 I = 17 mA 12V Resistors Combined 23. (a) What single value resistor could be used to replace the network shown ? Simplify parallel networks first. For 10 and 15, RE = (1/10 +1/15)-1 = 6.0 Ω. For 50,50,100 RE = (1/50 + 1/50 + 1/100)-1 = 20 Ω. Now RE = 6 + 24 + 20 = 50 Ω 10 Ω 50 Ω v1 50 Ω 15 Ω 24 Ω 3V 100 Ω 10 V I = 0.5 A 25 V (b) What is the Potential Difference across and the current through the 24 Ω resistor ? V24Ω = 25 – (10 + 3) = 12 V, I24Ω = I = 0.5 A 2.4 Ohm’s Law Conductors which obey Ohm’s Law are called Ohmic Conductors. Georg Ohm 1789 - 1854 The relationship between, the potential difference across, the current through, and the resistance of, a conductor was discovered by Georg Ohm and is known as Ohm’s Law Ohm’s Law stated mathematically is: V = IR Where: When expressed graphically, by plotting V against I, Ohm’s Law produces a straight line graph with a slope equal to resistance (R) V Rise Run V = Potential Difference in Volts (V) I = Current in Amps (A) R = Resistance in Ohms (Ω) Note the graph passes through the origin (0,0) as it must, since if both V and I are zero, resistance is a meaningless term. Rise Run = Slope = Resistance I Ohm’s Law (1) 24. A current of 2.5 mA is flowing through a resistor of 47 kΩ. What is the Potential Drop drop across the resistor ? V = IR = (2.5 x 10-3)(4.7 x 104) = 117.5 V 25. A 12 V battery is driving a current through an 20 Ω resistor, what is the size of the current flowing ? V = IR I = V/R = 12/20 = 0.6 amp 26. A resistor has a 48 V potential difference across it and a 2.4 A current flowing through it. What is it’s resistance ? V = IR R = V/I = 48/2.4 = 20 Ω Ohm’s Law (2) R = 1.2 kΩ 27. What are the readings on meters V and A ? V = VR = VSUPPLY = 12 V I = VR/R = 12/(1.2 x 103) = 0.01 A 28. (a) Determine the value of the current measured by ammeter A1 (express your answer in mA) Need to find equivalent resistance by simplifying parallel networks. Simplify parallel networks first. For 1.0k and 1.5k, RE = (1/1000 +1/1500)-1 = 600 Ω. For 500, 500, 1k; RE = (1/500 + 1/500 + 1/1000)-1 = 200 Ω. Now RE = 600 + 2400 + 200 = 3200 Ω A1 = 3.2 k Ω Now I = V/R = 25/3200 = 0.0078 A = 7.8 mA V A VP = 12 V 500 Ω v2 1 kΩ A2 500 Ω 1.5 kΩ 2.4 kΩ V1 1 kΩ v3 25 V Ohm’s Law (3) 1 kΩ (b) Determine the value of the potential differences measured by voltmeters V1, V2 and V3. 500 Ω v2 A2 500 Ω 1.5 kΩ V1 2.4 kΩ 1 kΩ V1 = Voltage across 1k, 1.5k combination. v RE = 600 Ω, so V1 = IRE A1 = (7.8 x 10-3)(600) = 4.68 V; 25 V V2 = voltage across 2.4 kΩ = (7.8 x 10-3)(2.4 x 103) (c) Determine the current measured by = 18.72 V; ammeter A2 V3 = Voltage across the 500, 500, 1k combination A2 = current through 500 Ω resistor = IRE = V/R -3 = (7.8 x 10 )(200) = 1.56/500 = 1.56 V = 3.12 x 10-3 A 3 2.5 Short Circuits Short circuits occur when the Resistive parts of a circuit are bypassed, effectively connecting the positive terminal of the power supply directly to the negative terminal providing a resistance free path for the current. The current immediately increases to its maximum. R2 This can be disastrous for the circuit causing rapid heating and possibly a fire. This situation is taken care of by the use of fuses, circuit breakers, “safety switches”, or residual current devices. (See chapter 5). VS Chapter 3 Non Ohmic Devices 3.0 Non Ohmic Conductors Conductors which do not follow Ohm’s Law are called Non Ohmic Conductors Devices such as diodes and transistors can be classed as non ohmics, but the best known non ohmic is the incandescent light globe. When a plot of Potential Difference against Current is drawn, it is not a straight line. A Typical “Characteristic Curve” for an Incandescent Light Globe V At High Voltages, Slope is steep = High Resistance I At Low Voltages, slope is shallow = Low Resistance Non Ohmics - Series 29. Two non ohmic conductors with “Characteristic Curves” as shown opposite are connected in series in a circuit as shown. 8 The voltage across device 1 is 6.0 V. 6 (a) What is the current through Device 2, 4 (b) What is the voltage across Device 2, 2 (c) What is the voltage of the battery powering the circuit ? Device 1 Device 2 Voltage (V) Voltage (V) 8 6 4 Current (I) 1 2 2 Current (I) 1 2 6.0 V Device 1 Device 2 (a) Voltage across device 1 = 6.0 V so current through device 1 = 0.5 A (read from graph) because devices are in series current is same through both. So I DEVICE 2 = 0.5 (a) Voltage across device 2 = 4.0 V (read up from 0.5 A on graph for device 2). (b) VSUPPLY = Sum of voltage drops around the circuit = 6.0 + 4.0 = 10.0 V Non Ohmics Parallel 30. Two devices with Characteristic Curves” shown are connected in parallel. The current through Device 1 is 1.0 A. (a) What is the voltage across Device 2 ? (b) What is the current through Device 2 ? (c) What is the voltage of the battery ? (d) the total current drawn from the battery ? 1.5 A Device 1 Device 1 Voltage (V) Device 2 Voltage (V) 8 8 6 6 4 4 2 0 2 Current (I) 1 2 0 Current (I 1 2 Device2 (a) If current through device 1 = 1.5 A, then voltage across it = 8.0 V (read from graph). In parallel network voltage is same across each member so VDEVICE 2 = 8.0 V (b) If voltage across device 2 = 8.0 V, current = 2.0 A (read from graph). (c) VSUPPLY = VDEVICE 1 = VDEVICE 2 = 8.0 V (d) Total Current = Sum of currents through each component = 1.5 + 2.0 = 3.5 A Chapter 4 Cells & Batteries 4.0 Cells and Batteries Electrical Cells (as opposed to plant and animal cells) are devices which perform two functions: 1. Charge Separation. 2. Charge Energisation. Charge Separation is the process of separating positive and negative charges to produce a POTENTIAL DIFFERENCE capable of driving a current around an external circuit. Charge Energisation is the process of providing the separated charges with the ELECTRICAL ENERGY they need to complete their journey around the circuit connected to the cell. A Single Cell A group of Cells ie. a Battery Batteries have a limited ability to separate and energise charge, they eventually go “flat”. See Slide 4.5 4.1 Power Supplies Power Supplies, (as opposed to cells and batteries) obtain their separated and energized charges from the mains supply to which they are connected, via the standard 3 pin plug. They rely on the power generation company to separate and energize the charge carriers at the power station. The power station remains “on line” at all times, so the power supply can operate indefinitely, i.e., it does not go “flat” like a battery. In all other senses, power supplies behave in a similar fashion to cells and batteries. 4.2 Electromotive Force (EMF) Electromotive Force (EMF) is not a true force in the Newton’s Laws sense, but it is a term used to describe the OPEN CIRCUIT VOLTAGE of a cell, battery or power supply. EMF is represented by the symbol (ε). The Greek letter epsilon. R “Open Circuit” means that no complete external circuit is connected to the battery or power supply and thus no current is being drawn. Consider the circuit shown With the circuit complete, a current is flowing and the P.D. across the power supply equals the P.D. across the resistor. With the switch open the current stops flowing, the voltage across the resistor falls to zero and the voltage reading across the power supply rises. The Voltage reading now is the EMF of the supply Cells and Batteries 31. The primary task of a battery or power supply is to: A: Supply electrons and energise them B: Provide energy for charge carriers C: Provide charge separation and energization. D: Separate electrons from protons. 32. The EMF of a battery or power supply is A: The Potential Difference of the supply when a current is being drawn. B: The Potential Difference of the supply when no current is being drawn C: The Potential Difference difference between the positive and negative terminals when they are short circuited. D: The Potential Difference difference between earth and the positive terminal. 33. When a battery or power supply is switched into an external circuit the Potential Difference measured across the terminals of battery or power supply will: A: Fall because a current is now flowing B: Rise because a current is now flowing C: Remain unchanged even through a current is now flowing D: None of these answers 4.3 Internal Resistance The reason the Potential Difference of the power supply falls when a current is drawn from it is the “Internal Resistance” of the supply. The internal resistance is: •The “price which must be paid” for drawing a current from the supply. •A measurable quantity and, as with all resistance, is measured in Ohms (Ω). The larger the current drawn from the supply, the greater the “cost” (in terms of energy wasted inside the supply), because of the internal resistance. This means less energy is available for the charge carriers to flow around an external circuit. A cell, battery or power supply can be represented as a pure EMF in series with a resistor, r, (representing the internal resistance). Power Supply r ε V1 With no external circuit connected (i.e. a so called “no load” situation), no current is drawn from the supply, and the voltmeter reading V1 will equal ε, the EMF of the supply. 4.4 Internal Resistance V2 The power supply now has an external circuit connected. This draws a current from the supply. ε This current also flows through the internal resistance r. This causes a potential difference = Ir across R that resistor. The voltage measured by V2 will now be less (by an amount Ir) than the EMF (ε) of the power supply. r I Mathematically: V2 = ε - Ir By replacing the fixed resistor (R) in the external circuit with a variable resistor, and changing the value of the resistance, a set of values for V2 and the corresponding current, I, can be obtained. Plotting these values gives the following. Voltage (V2) Intercept = ε This method allows you to calculate the internal Slope = - r resistance of the power Current (I) supply, cell or battery. Cells and Internal Resistance 34. A battery or power supply can be regarded as A: A pure P.D. source in parallel with a resistance B: A pure P.D. alone C: A pure P.D. source in series with a resistor D: A pure resistance in parallel with an EMF 35. A battery has an EMF of 9.0 V. When connected into a circuit drawing 25 mA the potential difference across the battery terminals in measured at 8.6 V. What is the internal resistance of the battery ? V = ε – Ir r = (ε – V)/I = (9.0 – 8.6)/(2.5 x 10-2) = 16 Ω Internal Resistance 36. A group of students set out to study the properties of a D cell battery. Using the following circuit and varying the resistance of the rheostat they collected the data shown. V 2 I2 I R Voltage (v) Voltage (V) (volts) Current (I) (milliamps) 0.10 120 0.25 100 0.45 70.0 0.60 50.0 0.70 35.0 0.85 15.0 (b) EMF = y intercept = 0.95 V 1.0 (c) Internal resistance (r) = negative of slope = -(0.85 – 0.25)/(15 x 10-3 – 100 x 10-3) = - (0.6)/(-75 x 10-3) = 8Ω 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 10 20 3 0 40 5 0 60 7 0 8 9 100 110 120 0 0 Current (mA) 4.5 A Flat Battery In a cell or battery, the chemical processes used to provide charge separation and energisation become less efficient as current is drawn from it. This shows up in an increase in the Internal Resistance of the battery. The internal resistance will continue to increase until the battery is no longer able to provide sufficient energy to perform its primary task (separation and energisation) and the battery is said to be flat. In testing a battery with a multimeter, you measure the EMF, which may seem fine, because you are not drawing a current from it. To properly test a battery it needs to be placed in a resistive circuit of some kind so that a current is drawn. Measuring P.D. across the battery now will now give a more realistic picture of the battery’s condition. Flat Battery 37. Explain why is not sufficient to simply measure the EMF of a battery to check if it is “flat” ? EMF does not measure the internal resistance of the battery and hence its ability (or otherwise) to provide a current to external circuit. Chapter 5 Fuses and Stuff 5.0 Fuses Fuses are primarily Safety Devices placed in circuits to limit the current flow to a certain (predetermined) value. Limiting the current in this way reduces the chance of fire caused by overheating in a circuit carrying excessive current. A Fuse is basically a short piece of thin wire which, when too much current tries to flow through it, overheats and then melts, breaking the circuit. In the electricity supply network fuses are present throughout the system and at the domestic or household end fuses are located in the “Fuse Box ” sometimes also called the “Meter Box”. Modern Meter Boxes have resettable fuses called “Circuit Breakers” instead of the old style porcelain former with its separate thin wire fuse. 5.1 Residual Current Interrupt Increasingly, Meter Boxes contain To understand the operation of the Residual Current Interrupt Devices (RCI), RCI you need to know that a current commonly called “safety switches” and in a wire causes a magnetic field Surge Arrestors. around that wire. Both are safety devices. The strength of the magnetic field The RCI is designed to protect people depends upon the size of the current. while surge arrestors protect electrical equipment. THE RCI AND THE TOASTER Active Wire The RCI operates using two coils to monitor the magnetic fields produced by the currents in both the active and neutral wires. Under normal conditions the Active and Neutral currents will be equal. This means the induced currents in the coils will also be equal and will cancel one another out inside the RCI. Neutral Wire RCI G.P.O. or Power point Coils Earth If the two A and N currents are different, as shown with some passing down the earth wire, due to a short circuit in the toaster, the RCI reacts by opening a switch in the active wire, cutting off the current. The RCI will respond in approx 0.03sec (less than a heartbeat) Safety 38. Which one or more of the following act as safety devices in electric circuits ? A: Fuses B: Safety switches C: Surge arrestors D: Short Circuits 39. RCI’s monitor the currents in A: The Neutral and Earth Lines B: The Active and Earth Lines C: The Active Line only D: The Active and Neutral Lines 5.2 Switches Switches break circuits by moving Opening the switch (turning it “off”) contacts apart. isolates the power point from the In the domestic situation switches supply. are always placed in the Active If the switch was placed in the Neutral Line. line the power point would remain live This is especially important for even with the switch “off” General Purpose Outlets (GPO’s) There are large numbers and types of more often called wall sockets or switches in use. They can be power points. Mechanical, Electromechanical or Electronic. Sample Mechanical Switches are shown: SPST Single Pole, Single Throw DPST Double Pole, Single Throw SPDT Single Pole, Double Throw DPDT Double Pole, Double Throw Switches 40. Identify each type of switch Double Pole Double Throw Single Pole Double Throw Double Pole Single Throw Single Pole Single Throw 5.3 Earthing The Earth is a giant “sink” for electricity, it will soak up electric charge. The name given to the process of connecting a circuit to the Earth is called “earthing” and the physical connection is via the Earth Wire. To better understand earthing, an understanding of domestic wiring is needed. Below is a sample domestic wiring system showing one power point only. The Earth is also physically Active Line Neutral Line connected to the neutral bar, holding it at Earth potential (voltage) of 0 volts. Main Fuse The Earth Wire provides a “resistance free” path to Meter The earth earth for any current that stake is a leaks from the active Fuses Main Switch solid copper and/or neutral lines. piece driven Meter Box Leaking current will about 2 m into choose to use the no (or Neutral Bar the ground low) resistance path to earth rather than the high Power point Earth Stake resistance path through a human. Earthing, as used in domestic wiring, is just another safety feature. 5.4 Electric Shock Electricity is dangerous! We all know this, it was drummed into us throughout our childhood. We can all remember the reaction of adults the first time they found us playing with electrical sockets at home. But exactly how dangerous is electricity and what does it do to our bodies ? The lowest recorded voltage at which death occurred was 32 V AC Domestic electricity in Australia is supplied at 240 V AC, at 50 Hz. If you are exposed to this supply for 0.5 sec and depending on the size of the current, the following effects will be experienced. Remember that 1 mA = 1/1000th of an Amp ( 1 mA = 1 x 10-3 A) Current (mA) 1 3 10 20 50 90 150 200 500 Effect on Body Able to be felt – slight tingling Easily felt – distinct muscle contraction Instantly painful - Cramp type muscle reaction Instant muscle paralysis – can’t let go Severe shock – knocked from feet Breathing disturbed - burning noticeable Breathing extremely affected Death likely Breathing stops – death inevitable Chapter 6 Electricity Consumption 6.0 Power Consumption In general, POWER is defined as the time rate of doing WORK or the time rate of ENERGY conversion. Mathematically: Where P = W/t = E/t P = Power (Watts) W = Work (Joules) E = Energy (Joules) Rearranging the equation we wet: t = time (secs) E = P.t so 1 Joule = 1 Watt.sec The Joule is a very small unit, too small for the Energy companies to use when it comes to sending out the bills to customers, so electricity is sold in units called kilowatt hours. (kWh). Have a look at your own electricity bill at home ! 1 kW = 1000 W and 1 hour = 3600 s So 1 kWh = 1000 x 3600 J = 3.6 x 106 J = 3.6 MJ. Electric Power 41. An electricity bill indicates the household used 117.5 kWh of electricity in a week. How many megajoules were used ? 1 kWh = 3.6 MJ so 117.5 kWh = (117.5)(3.6) = 423 MJ 42. What was the power consumption of the home (in Watts) ? P = E/t, U = 423 MJ = 4.23 x 108 J t = 1 week = 7 x 24 x 60 x 60 sec = 604800 s P = E/t = (4.23 x 108)/(6.048 x 105) = 699 W 6.1 The Kilowatt Hour A 100 W (0.1 kW) incandescent light globe which runs for 1 hour consumes 0.1 x 1 = 0.1 kWh of electricity. Cost to run @ 12c/kWh = 1.2 cents A 1500 W (1.5 kW) electric kettle which boils water in 5 minutes consumes 1.5 x 5/60 = 0.125 kWh of electricity. Cost to run @ 12c/kWh = 1.5 cents A 2000 W (2 kW) oven operating for 3 hours consumes 2 x 3 = 6 kWh of electricity. Cost to run at 12c/kWh = 72 cents Domestic electricity costs between 12 cents and 20 cents a kWh Running Costs 43. If domestic electricity costs 13.5 c per kWh. Calculate the cost of running (a) a 100 W light globe run for 1 hr, (b) a 1500 W kettle run for 5 mins and (c) a 2 kW oven run for 3 hrs. Light Globe = (0.1)(13.5) = 1.35 cents: Kettle = (0.125)(13.5) = 1.69 cents: Stove (6.0)(13.5) = 81 cents 6.2 Load Curves The demand on the electricity supply is not constant: •It varies from time to time during the day. •It varies from day to day during the week. •It varies from season to season during the year. This variation is best displayed on a “Load Curve” Blackouts or “Brownouts” are likely at these times 12 Midnight 6 am 12 noon 12 Midnight 6 pm 100 % Hot Day Summer Cold Day Winter 75 % Mild Day Spring 50 % Load Curves Questions 44. Why does the demand on a hot summer day exceed the demand on a cold winter’s day ? Hot Summer days means use of air conditioners, the greatest consumers of electrical power of all household appliances. In addition commercial air conditioners must also work harder thus consuming more electricity. 45. “Blackouts”, loss of supply often occur when demand exceeds supply. At what times and on what type of day are blackouts likely to occur ? Just after noon and just after 6 pm on hot summer days Ollie Leitl 2008