* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 10a.12 Italo Calvino, The castle of crossed destinies

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

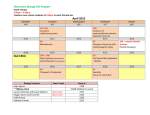

HUI216 Italian Civilization Andrea Fedi HUI216 (Spring 2007) 1 10a.1 St. Augustine (354-430) • He was born in Thagaste (now Suk Arras, Algeria), and died in Hippo (South of the modern Bona) • Was he a Berber? • St. Monica was St. Augustine's mother. She was a Christian, while St. Augustine's father was a pagan • In Chapt. 11-12 of book 9 of St. Augustine's Confessions, we can read about the circumstances of her death, in Milan, in the year 387, and we learn more about the relationship between mother and son. You can read the passage, if you want, at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/augustine/confessions.x ii.html HUI216 2 10a.1 St. Augustine (354-430): the Manicheans, St. Ambrose • Augustine was influenced by the Manichean heresy • Manicheans emphasized the battle of good vs. evil, considered two almost equal powers • The temptation to embrace a dualistic vision of the universe, where everything is so reassuringly black and white, where two powerful forces such as Good and Evil fight over the control of human history, has always been very strong • That simplification presupposes reasons to be Christian that appear easier to understand and, most importantly, easier to represent in the routines of daily life. It is less complicated to think of oneself as a soldier fighting a constant battle against sin and sinners, in life and in society, than it is to find God's call and also meaningful, creative ways to infuse one's faith in the diverse fields and activities of life • Augustine taught grammar and rhetoric in Thagaste, Carthage, Rome, then Milan (385) • In Milan he met Ambrose, the city's bishop. From him he learned about the allegorical interpretation of the Bible and of life in general HUI216 3 10a.1 St. Ambrose and the allegorical interpretation of the Bible • The allegorical interpretation is based on the assumption that the Bible was directed by God to the Church in general, not just to a single group in a specific place, or to a community that lived during a certain time • Everything in it has always meaning, and nothing is ever out of date or inapplicable to the present • God is constantly speaking to his creatures through his book (and through reality (nature and history) • The Christian has simply to uncover the hidden truth that is relevant for his/her own individual experience • In the explanation of the Bible, Ambrose and the Fathers of the Church move constantly from the literal and historical interpretation of the text to a variety of allegorical interpretations HUI216 4 10a.1 St. Ambrose and the allegorical interpretation of faith and life • Both the Bible and human life are seen as having multiple layers of signification: through the Bible and through all kinds of events God is communicating with each individual • "In allegorical exegesis the sacred text is treated as a mere symbol, or allegory, of spiritual truths. The literal, historical sense, if it is regarded at all, plays a relatively minor role, and the aim of the exegete is to elicit the moral, theological or mystical meaning which each passage, indeed each verse and even each word, is presumed to contain" (J.N.D. Kelly) • An example from the Old Testament: the allegorical interpretation of the episode of Jonah in the belly of the whale does not take away from the reality of Jonah's experience, and yet at the same time that story is read also as a prophecy of Jesus' death and resurrection, the belly symbolizing the tomb in which his body rested for three days HUI216 5 10a.1 St. Augustine: the conversion • 386: after a friend's visit, St. Augustine goes into his garden. He hears a child's voice repeating "Tolle, lege" ["Take up and read"]. He picks up St. Paul's epistles, and opens it at Rom. 13 • In line with the allegorical interpretation of reality, we have to assume that the child's voice is really that of the neighbor's son, and yet those words are also spoken to Augustine by God, indirectly, because nothing ever happens by chance • Reality is in itself a book with multiple meanings, multiple levels of signification: everything has a literal and a historical meaning, but also speaks of something else • Of course this view is somewhat distant from our modern reasoning, and medieval literature, where allegory is present everywhere, can be difficult to read and easy to misunderstand or to oversimplify HUI216 6 10a.1 St. Augustine: after the conversion • St. Augustine's Confessions • Contains autobiographical chapters, which constitute probably the first modern autobiography (as a history of the heart, not just a journal of material events) • Easter of 387: he is baptized by Ambrose • Back in Africa he becomes a priest, then the Bishop of Hippo HUI216 7 10a.1 Benozzo Gozzoli, San Gimignano (Tuscany): "Take up and read" (1465) HUI216 8 10a.1 Benozzo Gozzoli, San Gimignano (Tuscany): "The baptism of St. Augustine" (1464) HUI216 9 10a.2 Augustine on grace and salvation, on the sack of Rome • Often based on St. Paul's teachings • Central is the idea that without the grace of God one cannot be saved • Free will vs. predestination: see the following article from the Catholic encyclopedia: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06259a.htm • Even Martin Luther belonged to the Augustinian order • De civitate Dei (413-26): on God and the Roman empire • The City of God was written in the years following the sack of Rome by the Visigoths (410 CE) • St. Augustine decided to provide a systematic examination of Roman history • He explains how God intervened in the development of the Roman Empire (under which Jesus was to be born) HUI216 10 10a.2 St. Augustine on God and the Roman Empire • Romans were able, in his view, to maintain unity, peace and stability so that humankind would be ready to accept the gospel • Augustine defends the Christian faith from the accusations of those who saw in the sack of Rome a sign of the weakness of the new God accepted by the Romans, a God who seemed unable or unwilling to protect the city and its inhabitants, in spite of the fact that the majority of them had converted to Christianity during the previous 100 years • Augustine's ideas on the relationship between Roman and Christian history, and the pages he devoted to praising the virtues of the Romans, especially those from the age of the Republic, ended up promoting the acceptance of Greco-Roman civilization in medieval society/culture HUI216 11 10a.2 How St. Augustine read the classics • A passage that Prof. Donnell likes to quote often, shows how much Augustine believed in the fundamental harmony existing between GrecoRoman philosophy, specifically Platonism, and the Christian faith. It is a paragraph from the 7th book of the Confessions, in which Augustine explained how he found the words of the prologue to the gospel of St. John inside the book written by a disciple of Plato • 7.9.13 Thou procuredst for me…certain books of the Platonists, translated from Greek into Latin. And therein I read, not indeed in the very words, but to the very same purpose, enforced by many and diverse reasons, that In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God... HUI216 12 10a.2 How St. Augustine read the classics • ...the Same was in the beginning with God: all things were made by Him, and without Him was nothing made: that which was made by Him is life, and the life was the light of men, and the light shineth in the darkness, and the darkness comprehended it not. • And that the soul of man, though it bears witness to the light, yet itself is not that light; but the Word of God, being God, is that true light that lighteth every man that cometh into the world. • … But, that He came unto His own, and His own received Him not; but as many as received Him, to them gave He power to become the sons of God, as many as believed in His name; this I read not there. • http://www.georgetown.edu/faculty/jod/augustine/Pusey/bo ok07 HUI216 13 10a.2 Why Augustine read and valued the classics • It is undeniable that many of the Scriptures in the New Testament clearly show the influence that Greek culture already had on some of the authors of those texts, namely St. John, the apostle Paul and, to a certain extent, Luke • Paul and Luke certainly had studied in schools and with teachers that were familiar with principles of Greek philosophy as well as of classical rhetoric • In the case of John, very little we know for sure about his education, but that he had read books written by the disciples or followers of Plato or even those written by Plato himself there is no doubt, and biblical studies have pointed out that he was also a master in the use of rhetorical devices such as irony HUI216 14 10a.2 Why Augustine read and valued the classics • So it doesn't seem unreasonable that St. Augustine had recognized and that he valued the influence of classical philosophy on the Scriptures • This discovery must have shown him the way to reconcile values and ideas of the Greeks and the Romans with the new Christian ideology, which was originally, by virtue of its roots, essentially different from anything ever conceived in Greek or Roman culture • Finally we cannot overlook the fact that St. Augustine had been first a brilliant student and then for many years in teacher of rhetoric, one of the disciplines that really define classical culture HUI216 15 10a.3 St. Augustine: metaphors that he popularized and that are still popular among Christians • Life itself is like a book, or a divine scripture • everywhere we turn our eyes there are signs • the world can be read as an endless allegory • Life is a journey, or a pilgrimage • the final destination (Heaven or Hell) is much more important than the single steps or the path taken to get there • The city of God vs. the city of man • 1) the ideal community of the saints and believers • 2) the society of those overly concerned with earthly values, like the community created by Cain, the first biblical city, after he had killed his brother; or the one founded by Romulus, another who had murdered a sibling • heaven vs. earth = spirit vs. body HUI216 16 10a.4 The 4 Latin doctors of the Church, in a medieval manuscript: Augustine, Ambrose, Jerome, Gregory HUI216 17 10a.5 The Temporal Reward Which God Granted To The Romans (from St. Augustine's The city of God, 5.15) • With regard to those to whom God did not intend to give eternal life with His holy angels in His own celestial city..., if He had also withheld from them the terrestrial glory of that most excellent empire, a reward would not have been rendered to their good arts, -- that is, their virtues, -- by which they sought to attain so great glory • Compare to the episode of Limbus in Dante's Inferno, in The Divine Comedy HUI216 18 10a.5 Examples of the extraordinary virtues of the ancient Romans, from The city of God • ...another Roman chief, Torquatus, slew his son, not because he fought against his country, but because, being challenged by an enemy, he through youthful impetuosity fought, though for his country, yet contrary to orders which his father had given as general; • and this he did, notwithstanding that his son was victorious, lest there should be more evil in the example of authority despised, than good in the glory of slaying an enemy • if, I say, Torquatus acted thus, wherefore should they boast themselves, who, for the laws of a celestial country, despise all earthly good things, which are loved far less than sons? HUI216 19 10a.5 Examples of the virtues of the Romans: Mucius • If Mucius, in order that peace might be made with King Porsenna, who was pressing the Romans with a most grievous war, when he did not succeed in slaying Porsenna, but slew another by mistake for him, reached forth his right hand and laid it on a red-hot altar, ...so that Porsenna, terrified at his daring, and at the thought of a conspiracy of such as he, without any delay recalled all his warlike purposes, and made peace • if, I say, Mucius did this, who shall speak of his meritorious claims to the kingdom of heaven, if for it he may have given to the flames not one hand, but even his whole body, and that not by his own spontaneous act, but because he was persecuted by another? HUI216 20 10a.5 Ferdinand Bol, Titus Manlius Torquatus Beheading His Son (1661-63), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam HUI216 21 10a.5 Rubens, Mucius Scaevola and Porsenna (1620, Budapest) HUI216 22 10a.5 Giambattista Tiepolo, Mucius Scaevola (1750-53), Würzburg HUI216 23 10a.5 The virtues of the Romans, from The city of God • These despised their own private affairs for the sake of the republic, and for its treasury resisted avarice, consulted for the good of their country with a spirit of freedom, addicted neither to… crime nor to lust • By all these acts… they pressed forward to honors, power, and glory; they were honored among almost all nations; they imposed the laws of their empire upon many nations; and at this day, both in literature and history, they are glorious among almost all nations • There is no reason why they should complain against the justice of the supreme and true God, they have received their reward HUI216 24 10a.6 Christianity and Roman civilization • The mission of the Roman empire in Dante's The Divine Comedy • The Roman Republic in Dante's The Divine Comedy • when Dante, the protagonist of the Comedy, reaches the center of the earth, where Satan is, he finds there the three worst sinners in human history: while the first, Judas, is an obvious choice, the other two, Brutus and Cassius (who had conspired to kill Julius Caesar), can only be understood in the context of the deep appreciation of classical civilization by medieval intellectuals, appreciation which was shaped and fostered by scholars such as St. Augustine • The preservation of Roman/Greek culture • architecture and terminology: duomo (dome), cathedral (<throne), basilica, curia, romanesque • the use of Latin by the Church HUI216 25 10a.6 St. Augustine and medieval culture • Augustine, with a few others, was instrumental in convincing the Christian community that GrecoRoman civilization, in its greatest manifestations, was largely compatible with Christian ideology • Therefore Medieval society was based on the combination of the Roman heritage and Christian culture • Original Greco-Roman elements found their ways in religious poems, such as those written by St. Francis of Assisi and by Dante • Theology and classical philosophy • the philosophical theories of Aristotle and Plato were often use to confirm and explain, or even to provide the foundation of Christian theology HUI216 26 10a.6 The Christian Church and Roman culture • The Christian church borrowed ideas and practices from Roman culture • from the Roman arts and architecture, the typology and the terminology for different kinds of Churches • from the Roman government and administration, the attires of priests and bishops • just consider some of the mosaics in Ravenna, http://www.hp.uab.edu/image_archive/ulj/uljc.html [6th century CE] • in this image, http://www.hp.uab.edu/image_archive/ulj/mosaic51.jpg, priests are on your right and members of the court are on your left: notice the many similarities HUI216 27 10a.7 Conclusions • By suggesting that the success of the Roman Empire was part of God's plan, and that it was not by chance that Jesus was born under Roman authority, Augustine established the premise for the preservation of Greek and Roman culture in an integrally Christian society such as that of the Middle Ages • It is true that classical culture was at times and in different places ignored or misunderstood during the Middle Ages, but it is a fact that, among other things, the Church itself invested valuable resources in the construction and the maintenance of libraries that included scores of classical texts HUI216 28 10a.7 Conclusions • Medieval scholars and theologians may have at times attacked or rejected classical philosophers and pagan poets, but they seldom questioned their importance, a fact that seems almost natural now, but which was extraordinary in ancient times, considering how many civilizations have come and gone leaving so few traces (other than those rediscovered thanks to modern archeology) • The fact that a poet like Dante, more than 800 years after the fall of the Roman Empire, could give so much relevance in his Divine comedy to its culture and its representatives is a real paradox, one that Augustine is at least partially responsible for • see for example the treatment of the Roman Empire in the sixth Canto of Paradise, http://www.italianstudies.org/comedy/Paradiso6.htm HUI216 29 10a.8 From the Roman Empire to the Middle Ages • The Eastern Roman empire; the Franks in Italy; the clashes between the Papacy and the Empire • Chivalric literature • Chivalric literature in Italian culture; Ariosto's Orlando enraged, Calvino's Castle of Crossed Destinies; the Sicilian pupi HUI216 30 10a.9 The Middle Ages: the term – Localization and fragmentation • The term Middle Ages was created by humanists to stress the point that their own culture was superior to that of medieval scholars, intellectuals, writers and artists • During the early Middle Ages a system such as feudalism was established to cope with the problems and the necessities of societies which had very limited resources after the collapse of the highly organized administrative/economic system built by the Romans • The localization of the economy and of military defense, and, as a consequence, the fragmentation of political jurisdiction, provided the means of survival during a difficult time HUI216 31 10a.9 The Middle Ages: society and culture • Society was less structured, and technology really suffered a cutback from the age of the Romans • However, culturally the Middle Ages, even during the first few centuries, saw great achievements in all fields, and after the year 1000 philosophy, literature, historiography and the arts developed greatly • It has become easier to condemn the culture of the Middle Ages, mostly because many of the religious practices and ideals of the authors and artists who lived and worked during those times have fallen out of fashion • Nobody can deny that it was a grandiose attempt to renew culture, on the base of Greco-Roman civilization, and on the attempt to unify all aspects of life under the umbrella of religious principles HUI216 32 10a.9 The Middle Ages: the dark age? • One may disagree with this attempt to make religion such an integral part of society, but do not focus just on the persecution of heretics or the burning of witches, especially since those phenomena grew and became systematic exactly during the Renaissance, at the beginning of the so called modern era • For most of the Middle Ages there was usually more freedom than in modern structured societies • Satire even at the expense of members of the Church or the government was widespread, and authors such as Dante or Boccaccio were criticized but did not have to endure, while they were alive, any form of official HUI216 33 censorship 10a.9 The originality of medieval culture • Even literature and the arts for most of the Middle Ages were produced in a format that is for us often difficult to grasp and understand in its entirety, and with all its subtleties • The widespread use of allegory and symbolism, and of multiple levels of signification make for endless albeit interesting debates among scholars on the true intentions of Dante or Giotto • Overall it was a great civilization, even if you may very well choose to disagree with some of the principles that their social/cultural project was based on HUI216 34 10a.10 The Eastern Roman Empire expands its influence (6th century) • Under the Emperor Justinian (527-565), the Byzantines reconquered Italy (Ravenna was the center of their domination of the peninsula), and areas of the Western Mediterranean • This partial reunification was short-lived, because soon the Lombards, a Germanic tribe, invaded Italy, settling especially in Lombardy, Northern Tuscany, Umbria, and Campania • Constantinople was besieged by Avars (629) • The battle of Yarmuk, in Syria (636), marked the first great victory of the Muslims over the Byzantines • http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/yarmuk.html HUI216 35 10a.10 The Franks VS. the Arabs Charlemagne (742-814), king of the Franks • The prophet Mohammad (ca. 570-632) • 622: the year of the Hegira (Flight of the Prophet) marks the beginning of the Moslem calendar: Mohammad leaves Mecca to escape persecution, and reaches Yatrib (later Medina), where his preaching is more successful • 732: in just 110 years the Arabs conquer large areas of the Middle East, North Africa, Spain, and penetrate into France, where they are defeated, at Poitiers, by the Franks of Charles Martel • c. 827-1060: the Arabs in Sicily, http://www.pitt.edu/~eflst4/Islam_in_Sicily.html (click to read a brief, simple description of their domination of the island) • 770 Charlemagne marries Desiderata, daughter of the Lombard king Desiderius • 774 responding to the Pope's plea for help, Charlemagne conquers the lands of his father-in-law after the siege of Pavia • 775-796 Charlemagne attacks and defeats the Saxons and the Bavarians in Germany, the Avars in Austria and Hungary HUI216 36 10a.10 Charlemagne • 800 On Christmas Day, Charlemagne is crowned Holy Roman Emperor by pope Leo III • 814 Charlemagne dies • 843 Charlemagne's empire is divided • If you want to know more, read a few paragraphs (par. 24-28) from Einhard's Life of Charlemagne, (written circa 817-30): • http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/einhard.html • Somewhat humorous, in it, are the attempts to cover Charlemagne's ignorance HUI216 37 10a.10 The Papacy and the Empire • The issue of the real source of all political power (and its legitimacy) dominates the Middle Ages • Two powers or authorities, spiritual and temporal, each independent within its own domain? • "render to Caesar the things that are Caesar's and to God the things that are God's" (The Gospel of Mark, 12.17) • For Dante (1265-1321), the pope and the emperor are like two suns, shedding light upon man's spiritual and temporal paths • The metaphor used to characterize the opposite political view is that of the sun and the moon: the pope is the sun, he projects on the emperor the authority that he emanates naturally as the representative of God; the emperor (the moon) depends on him HUI216 38 10a.11 Chivalric literature: secular & religious • 778 Charlemagne's rear guard is attacked while leaving Spain • Chivalric literature is largely based on the defeat of Count Roland and of the other paladins • You can read an excerpt from the French Chançon de Roland (XII century): http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/roland-ext.html • Orlando enraged, by Ariosto: XVI-century best-seller • Italo Calvino, Edoardo Sanguineti, Gesualdo Bufalino, and Gianni Celati are important modern Italian writers who were inspired by chivalric literature • The Sicilian pupi [=puppets] is an old form of theatrical entertainment, still popular in Italy and in some of the Italian immigrant communities around the world HUI216 39 10a.11 The pupi siciliani: pictures and suggested readings • http://www.pupisiciliani.com/eng/Default.htm • http://www.teatropupimacri.it/index_en.htm HUI216 40 10a.11 The pupi siciliani: the great modern pupari Mimmo Cuticchio Don Vincenzo Garifo > HUI216 41 10a.12 Italo Calvino, The castle of crossed destinies (1969) HUI216 42 10a.12 Italo Calvino, The castle of crossed destinies (1969) HUI216 43 10a.12 Italo Calvino, The castle of crossed destinies (1969) HUI216 44 10a.12 Italo Calvino, The castle of crossed destinies HUI216 45 (1969) 10a.12 Italo Calvino, The castle of crossed destinies (1969) HUI216 46 10a.12 Italo Calvino, The castle of crossed destinies (1969) HUI216 47 10a.13 Feudalism • A political system in place in Europe and Asia (Japan and China) • A contractual relationship among single members of the upper classes • One nobleman (the vassal) becomes the man of another (the lord) by swearing homage and fealty • Vassalage brought with it a fief -- land held in return for military service • With the fief went rights of governance and of jurisdiction over local inhabitants HUI216 48 10a.13 The pyramid of power inside Feudalism King or Prince Duke Duke Baron Marquis Knight Count Knight Marquis Count Baron Baron Marquis Count Duke Baron Baron Baron Knight HUI216 49 10a.13 Feudalism was characterized by… • A pyramidal form of hierarchy, with governmental power spreading over various castle-dominated districts and downward through lesser nobles • Feudalism resembles a pyramid, with the lowest vassals at its base and the lines of authority flowing up to the peak of the structure, the king • The localization of political and economic power in the hands of lords and their vassals • They exercise that power from the base of the castles • These notes were originally taken from http://www.mc.maricopa.edu/anthro/lost_tribes/Feudalism.h tml. You can now find them here: • http://www.mc.maricopa.edu/dept/d10/asb/anthro2003/glues/feu dalism.html HUI216 50 10a.13 The castle of Serravalle (Tuscany, X-XIII): typical medieval castle, on a hill between two valleys, with watchtowers (one later transformed into a bell tower) HUI216 51 10a.13 Lord and vassal: mutual rights and obligations • The lord owed his vassal protection • The vassal • owed his lord a number of days per year of offensive military service • garrisoning a castle • owed his lord a fee when he succeeded to his fief • was expected to contribute to the lord's ransom were he captured, and to his military expenses • had to share the financial burden when the lord's eldest son was knighted and his eldest daughter married HUI216 52 10a.13 Lord and vassal: mutual rights and obligations • A vassal had to seek his lord's permission to marry off his daughter or to take a wife • Should the vassal die leaving a widow or minor children, they were provided for by the lord; should the vassal die without heirs, his fief reverted to the lord • Feudalism in Southern Italy survived well into the XIX century • the Mafia imitated its structure, in its relationship with the wealthy landowners and the peasants • the public administration shows traces of feudal culture: Italian state employees do not always act as civil servants; they behave as trustees controlling a fragment of the administration's powers HUI216 53