* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Lecture 2 The Law of Demand

Natural gas prices wikipedia , lookup

Grey market wikipedia , lookup

Revenue management wikipedia , lookup

Gasoline and diesel usage and pricing wikipedia , lookup

Pricing science wikipedia , lookup

Yield management wikipedia , lookup

Dumping (pricing policy) wikipedia , lookup

Pricing strategies wikipedia , lookup

Service parts pricing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing channel wikipedia , lookup

Perfect competition wikipedia , lookup

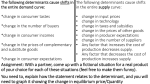

Lecture 3 The Law of Demand ■ Our objectives: ► Explain individual choices among unlimited wants in a world of limited resources ► Develop a theory that helps us better understand and predict human actions ►What do people (our customers) want? Simple(?) Application of Law of Demand Saved Pepsi 1931 Pepsi was bankrupt. It and Coke both produced 6 oz (1/6th liter) bottles of sodas. Years of advertising had not worked for Pepsi. It then made and sold 12 oz (1/3 liter) bottles of soda for twice the usual price—no results. It then sold 12 oz (1/3 liter) bottles for same price as Coke’s 6 oz bottles. Sales sky rocketed; the company was saved. A Very Difficult Issue What we measure in demand is a reflection of individual desires. Daniel Bernoulli, a mathematical genius who lived in Switzerland, noted, in 1738, that people seek goodness or pleasure (utility). We do not seek smartphones because they are smartphones but because they are useful and give us pleasure. Use and pleasure cannot be measured, only approximated. This is behind the law of demand. A Note on Value, Scarcity, and Price as Related to Demand Why do people want what they want? The diamond-water paradox. Scarcity need not ≠ highly valued (snake meat) Low cost need not ≠ low value (lock box key) Markets reflect what people value in relationship to current availability. Demand is our best understanding of what people value—given current conditions. The Law of Demand ■ Holding all other relevant factors constant, the lower (higher) the price of a good, the greater (lower) will be the quantity demanded. ► Like all scientific propositions, it is a ceteris paribus (“other things equal” or “other things constant”) statement ► Note: - Price means opportunity cost; - Good means anything people value Why focus on the Law of Demand? This is the most powerful proposition in economics. ► Irrigation design in arid and wet climates ► Building heights in cities compared to small towns ► The seasonal pattern of vegetable prices ► The shape of waterfront properties ► Electricity prices and automatic switches ► Etc., etc., etc. Example Law of Demand applies to all “goods” – legal or illegal Some common notations D = Demand S = Supply P = Price Q = Quantity MC = Marginal Cost AC = Average Cost MR = Marginal Revenue TR = Total Revenue The Demand Function: Some Definitions The relationship between quantity consumed and the factors determining that: D = f (P, PS, PC, I, E, T, etc.) ■ Price of the good in question—determines the location along a demand curve ■ Other variables (relevant factors) determine the placement of a demand curve: ► Prices of related goods (substitutes and complements) ► Income of buyers ► Tastes (preferences) of buyers ► Expectations held by buyers, regarding the future ► Other matters particular to a certain good The Role of Tastes ■ They are very hard to measure, so we generally ignore them, but we know they exist. ■ Look to marketing and psychology for guidance here, not economists! ■ For economists, tastes are often the unexplained portion of consumption Expectations ■ Difficult to measure or operationalize — but real. ■ When measurable, include in the analysis. But experience shows—measures are very poor predictors of actions. The Consumer Confidence Index (Conference Board) was at 115 in June 2007; down to 26 in March 2009. Ex post. (59 in July 2011) ■ Like tastes, these can be used to “explain” anything “Consumer Confidence” or Expectations tends to lag the economy. After recessions ended, still low confidence. University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index This or that? ■ Substitutes: Essentially, goods used in place of each other— same geographic market; similar performance characteristics. What is a substitute in one market may not be seen by consumers as such in another market—orange juice and orange soda. ► Different brands of gasoline; robots in Renault factory in France v. workers in Renault factory in Russia (former Lada) paid $1,200 mo.; movie theater v. downloads; corn or sugar in ethanol. Related Goods ■ Complements: Essentially, goods used together ► Computer hardware and software; tennis balls and rackets; airplane travel and hotel rooms; Google maps and discount coupons; growing corn for ethanol and Deere tractors Changes in the Price of Related Goods ■ Goods X and Y are substitutes if: ► A change in price of X changes demand for Y in same direction - Px up implies Dy up (Dy shifts to the right) - Px down implies Dy down (Dy shifts to the left) ► Effect of change in Py on Dx is also in same direction More on the Prices of Related Goods ■ Goods V and W are complements if: ► A change in price of V changes demand for W in opposite direction: - Pv up implies Dw down (Dw shifts to left) - Pv down implies Dw (Dw shifts to right) ► Effect of a change in Pw on Dv is also in opposite direction Changes in Income ■ Normal Goods: ► Change in income changes demand in same direction - Higher income causes increase in demand - Lower income causes decrease in demand ► ”Superior” good is a variant: change in demand due to income change is quite large ■ Inferior goods: ► Change in income changes demand in opposite direction - Higher income causes decrease in demand - Lower income causes increase in demand Terminology: Used to avoid confusion ■ Changes in quantity demanded: ► Caused by changes in own price of good means movement along a given demand curve ■ Changes in demand: ► Caused by changes in other factors: - Prices of other goods - Income - Expectations, etc. ► Means a shift of the entire demand curve Summarizing the Demand Curve The demand curve is a simple way of expressing a complex market. Strip it to the essentials to think about it. The curve represents the individual values of many different existing and potential demanders. All that information is imagined to be captured in that little curve to help us focus our thinking about the basics. Change in Price A change in the price of a good means a movement along a demand curve. Price Pa Pb Demand Qa Qb Quantity/time Change in Demand A change in a factor that determines demand, besides the price of the good itself, causes the Demand curve to shift. Example: Increase in price of substitute or increase in income causes an increase in demand. Price Da Pa Db Qa Qb Quantity/time Deriving a Real Demand Curve Define your market: Price Boulder, Colorado, over time; consumption of water by people .74 served by city water; price per 1,000 gallons; billions gallons/yr. .50 consumed by demanders. Demand .36 Year 1968 1972 1977 1982 Price $0.28 $0.36 $0.50 $0.74 Quantity 29 19 13 9 .28 0 9 13 19 29 Quantity What else would you want to know? The Demand curve plots the relationship between price and quantity demanded – nothing else – everything else is held constant But in the real world, other things are not constant, so what else would you want to know if you wanted to understand that market better? Name likely relevant factors: Demand analysis 1. 2. 3. How would demand for hair replacement treatment be likely to change if the following occurs? A fall in the price of treatment. A rise in income. A rise in the divorce rate. Clever sales pitch A British cellphone company promised new subscribers in November and December that all calls on Christmas Day, December 25, would be free. What would you expect happened to the volume of calls that day? Question on changing demand Trying to predict future demand, GE research showed that the average size of the American family was declining and so was the average square footage of houses. How would you think this impacted the demand for the design of, say, refrigerators? Key Point from Peter Drucker Most important question sellers must ask: “What is value to the customer?” Sellers often think they know, but do not. The customers do not buy a product; they buy value. Demanders are buying a product to satisfy a want. Do not guess what customers want—carefully evaluate what they want. Evaluate products from customers’ viewpoint, not how the producer knows it works.