* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download What does the ocean floor look like

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

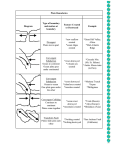

What does the ocean floor look like? by Dr. Rondi Davies We can all imagine a walk across North America: crossing the Mississippi, traversing the Great Plains, scaling the Rockies. But what would it be like to walk from New York Harbor to the coast of Great Britain? Would the land above water resemble the land beneath it? What does the ocean floor look like? You might be surprised. Below the surface of the ocean’s great blue expanse is a terrain more varied and dramatic than any landmass on earth: mountains taller than Everest, chasms deeper than the Grand Canyon, and plains more expansive than the Siberian steppes. Let's take a walk. Topography of the North Atlantic Ocean. The continental crust extends into the ocean for several miles, where it becomes the continental margin. The rest of the ocean is called the ocean basin: the deep sea floor that extends for thousands of miles with an average depth of 3,795 m (12,450 ft) below sea level, compared to an average height of 840m (2,755 ft) above sea level for landmasses. ©AMNH A walk across the ocean floor Our journey begins with a shallow descent from a mid-Atlantic beach to the continental shelf, a narrow ribbon of seafloor that extends around the world’s continents and ranges between 30 and 1300 km wide. At the edge it’s only about 200m deep. A uniform layer of mud and other sediments that originated on land covers most of the continental shelf. Most fish are caught in its teeming waters, which are also home to the bulk of the oceans’ vegetation and animal life. The edge of the shelf is the sea that most of us are familiar with, where we swim, fish, and go boating; it’s relatively warm and shallow. Next we reach the continental slope, where the sea floor begins its descent to the depths. Typical slopes have an incline of 4 degrees, although they can be as steep as 25 degrees. Cutting through parts of the slope are immense V-shaped canyons that wind outward to the deep sea and often connect to the mouths of rivers. (When sediment that has accumulated on the shelf becomes unstable or is shaken by earthquakes, it can avalanche down these canyons. This can trigger tsunamis — powerful waves that can travel for thousands of kilometers across the surface of the ocean.) The continental rise, at the base of the continental slope, is where sediments have descended from the continental shelf and accumulated. The width of the rise can vary from 100 to 1,000 km, and it has a very gradual slope. Now that we’ve hit the deep ocean basin, we can set out on the long trek across the ocean floor. All the way down At depths below about 4,000 m (2.5 mi), the seafloor is called the abyssal plain. It is essentially flat because the rugged topography of the underlying basaltic crust is draped in sediment that can be up to five km (three mi) thick. The abyssal plains cover 25% of the Earth’s surface. Great expanses appear barren, but in fact the animals that live on the seafloor — called benthos — are abundant and diverse. Most are invertebrates (such as sea anemones, sponges, corals, sea stars, sea urchins, worms, bivalves, and crabs) that have adapted to the cold water and high pressure with slow metabolisms. Near the center of the ocean basin we find ourselves climbing a mid-ocean ridge: a line of volcanoes about 2,500 m (1.2 mi) high and 70,000 km (43,000 mi) long that stretches across the ocean floor and around the Earth like the seams on a baseball. Also called spreading centers, these mid-ocean ridges are where new oceanic crust is created. Luckily, we’re not in the Pacific Ocean (or further south in the Atlantic), where we’d have to hurdle an ocean trench or two. Three to six km deeper than the adjacent ocean floor, these are the deepest places on the Earth’s surface. (The most famous one is the Mariana Trench of the western Pacific. It’s 11,022 m deep — way deeper than Mt. Everest is high — and about 2,550 km (1,584 mi) long and 70 kilometers (43 mi) wide.) And along our journey, we’re bound to hit seamounts and guyots, small, circular, steep-sided volcanic structures about one kilometer high, which do not rise above sea level. They can be found in groups of up to 100, or by themselves. Most are inactive volcanoes that formed at mid-ocean ridges, though some are thought to result from hot-spot volcanism. (Hot-spot volcanism occurs at places where enormous heat rising from the inner Earth is concentrated. These spots stay stationary while the rocky plates that make up the Earth’s surface move across them An island can be eroded away to a flattopped submerged seamount in a few millions years. Some submarine volcanic mountains, guyots, never rise above the surface of the ocean. Other underwater volcanic activity is characterized by broad, flat surfaces: oceanic plateaus.©AMNH The result is chains of volcanoes like those that make up the Hawaiian Islands.) The ocean floor also has strange features called oceanic plateaus: thick sections of ocean crust that represent massive outpourings of lava, which may have been triggered by large meteorite impacts. After a 4,000 mile trek across the Atlantic Ocean basin, we begin climbing up the continental margin to dry off on the west coast of Ireland. Back to the land So what does the ocean floor look like? A vast expanse of seemingly barren desert, punctuated by some of the most intense geologic features and activity on the planet — hardly the homogenous place suggested by those miles and miles of unbroken blue. "We know more about the surfaces of the Moon and Mars than we do about the floor of the ocean." —Sylvia Earle, Ocean Explorer Exploring the ocean was once limited to what could be seen from shore or a ship or by diving down a few meters. Then, commerce and curiosity drove explorers from ancient Egypt, Phoenicia, China and Polynesia to venture over the horizon. It wasn't until the 19th century that American and European ships made the first scientific voyages. Today, small submarines have become invaluable research vessels for scientists. These and other new tools — satellites, robotic vehicles and self-propelled, datalogging buoys — are helping us discover new species, uncover new resources, and understand how interconnected the oceans are with the rest of the planet. Still, less than 5% of the deep ocean has been explored. Imagine the possibilities. Assessment Questions Answer the following questions on a clean sheet of paper and place in your notes. 1) Which 3 features make up the continental margin? List 5 features from this article that are associated with the deep ocean basin. 2) Review: Based on Plate Tectonics describe how the following features form? Mid-ocean ridges, trenches, seamounts.