* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chapter 10

Non-monetary economy wikipedia , lookup

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Transformation in economics wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Post–World War II economic expansion wikipedia , lookup

2000s commodities boom wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

Long Depression wikipedia , lookup

Stagflation wikipedia , lookup

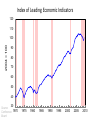

PART IV Business Cycle Theory: The Economy in the Short Run Introduction to Economic Fluctuations Chapter 10 of Macroeconomics, 8th edition, by N. Gregory Mankiw ECO62 Udayan Roy Short-Run Fluctuations • We have discussed the behavior of an economy in the long run • In the short run, the economy fluctuates around its long-run path • We need to understand why these fluctuations happen … • … and what can be done to stabilize the economy—as far as possible—when fluctuations occur BUSINESS-CYCLE FACTS Some facts about the business cycle • GDP growth averages 3 to 3.5 percent per year in the US over the long run • But there are large fluctuations in the short run. • Consumption and investment fluctuate with GDP, but consumption tends to be less volatile and investment more volatile than GDP. • Unemployment rises during recessions and falls during expansions. – Okun’s Law: there is a reliable negative relationship between the GDP growth rate and changes in the unemployment rate. Growth rates of real GDP, consumption Percent change from 4 quarters earlier Average growth rate 10 Real GDP growth rate 8 Consumption growth rate 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Growth rates of real GDP, consumption, investment Percent change from 4 quarters earlier Investment growth rate 40 30 20 Real GDP growth rate 10 0 Consumption growth rate -10 -20 -30 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Unemployment Percent of labor force 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Okun’s Law Y 3 2 u Y 10 Percentage change in 8 real GDP 1951 1966 1984 6 2003 4 1971 1987 2008 2 0 1975 2001 -2 1991 1982 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 Change in unemployment rate Index of Leading Economic Indicators • Published monthly by the Conference Board. • Aims to forecast changes in economic activity 6-9 months into the future. • Used in planning by businesses and government, even though ILEI is not a perfect predictor. Components of the ILEI • Average workweek in manufacturing • Initial weekly claims for unemployment insurance • New orders for consumer goods and materials, adjusted for inflation • New orders, nondefense capital goods, adjusted for inflation • Index of supplier deliveries (vendor performance) • New building permits issued • Index of stock prices • Money supply (M2), adjusted for inflation • Yield spread (10-year minus 3-month) on Treasuries • Index of consumer expectations Index of Leading Economic Indicators 120 110 2004 = 100 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 Source: 30 Conference 1970 Board 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 SHORT-RUN PRICE STICKINESS IS THE ROOT CAUSE OF FLUCTUATIONS Time horizons in macroeconomics • Long run Prices are flexible, respond to changes in supply or demand. • Short run Many prices are “sticky” at a predetermined level. The economy behaves very differently when prices are sticky. Recap of classical macro theory (Chaps. 3-9) • Output is determined by the supply side: – supplies of capital, labor – Technology – Y = F(K, L) • Changes in demand for goods and services (C, I, G) only affect prices (r), not output. • Assumes complete flexibility of overall price level (P). • Applies to the long run. When prices are sticky… … output and employment also depend on demand, And demand is affected by: – fiscal policy (G and T) – monetary policy (M) – other factors, like exogenous changes in C or I The role of price stickiness • When P is flexible, recessions would not occur – Under price and wage flexibility, if any recession did occur it would quickly be over … – … because unemployed workers would accept lower and lower wages, prices would drop, and customers would flock to the malls, thereby ending the recession • To explain why recessions do in fact occur, we therefore need to assume that prices are sticky or rigid “Price Stickiness” • Price stickiness does not necessarily mean that the overall level of prices (P) is constant • All that price stickiness means is that P has stopped responding to the economic factors that you would expect to affect P • P may be increasing or decreasing, but in that case it would be doing so purely on momentum, and not because of some economic cause The role of shocks • Price stickiness helps us explain why an economy that has fallen into a recession may continue in a recession • But price stickiness does not explain why the economy got into trouble in the first place • For that we need shocks that can explain why businesses may suddenly see there customers stop buying The role of shocks • • • • • • Consumption function: Co + Cy(Y – T) Investment function: Io − Irr Net exports function: NXo − NXεε Fiscal policy (G and T) Monetary policy (M) Business costs (for example, costlier imported oil) • These shocks can throw an economy off its long-run path • Price stickiness then impedes a quick bounce back to the long-run path STABILIZATION POLICY Fiscal and Monetary Policy • We have seen that, in the long run, changes in G and T have no effect on Y • In the short run, G and T can affect Y • We have seen that, in the long run, changes in M affect only P and have no effect on Y – Recall “classical dichotomy” and “monetary neutrality” from chapter 4 • In the short run, M cannot affect P, which is sticky, but it can affect Y • Therefore, G, T and M can be used to stabilize Y and other economic variables CASE STUDY: SHOCKS TO BUSINESS COSTS Supply shocks • A supply shock alters production costs, affects the prices that firms charge. (also called price shocks) • Examples of adverse supply shocks: – Bad weather reduces crop yields, pushing up food prices. – Workers unionize, negotiate wage increases. – New environmental regulations require firms to reduce emissions. Firms charge higher prices to help cover the costs of compliance. • Favorable supply shocks lower costs and prices. CASE STUDY: The 1970s oil shocks • Early 1970s: OPEC coordinates a reduction in the supply of oil. • Oil prices rose 11% in 1973 68% in 1974 16% in 1975 • Such sharp oil price increases are supply shocks because they significantly impact production costs and prices. CASE STUDY: The 1970s oil shocks 70% Predicted effects of the oil shock: • inflation • output • unemployment …and then a gradual recovery. 12% 60% 50% 10% 40% 8% 30% 20% 6% 10% 0% 1973 1974 1975 1976 Change in oil prices (left scale) Inflation rate-CPI (right scale) Unemployment rate (right scale) 4% 1977 CASE STUDY: The 1970s oil shocks 60% Late 1970s: As economy was recovering, oil prices shot up again, causing another huge supply shock!!! 14% 50% 12% 40% 10% 30% 8% 20% 6% 10% 0% 1977 4% 1978 1979 1980 Change in oil prices (left scale) Inflation rate-CPI (right scale) Unemployment rate (right scale) 1981 CASE STUDY: The 1980s oil shocks 40% 1980s: A favorable supply shock-a significant fall in oil prices. As the model predicts, inflation and unemployment fell: 10% 30% 8% 20% 10% 6% 0% -10% 4% -20% -30% 2% -40% -50% 1982 0% 1983 1984 1985 1986 Change in oil prices (left scale) Inflation rate-CPI (right scale) Unemployment rate (right scale) 1987