* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download ch19_5e

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

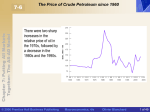

19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Now we must be able to distinguish between the domestic demand for goods and the demand for domestic goods. Some domestic demand falls on foreign goods, and some of the demand for domestic goods comes from foreigners. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 1 of 33 19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy The Demand for Domestic Goods In an open economy, the demand for domestic goods is given by: Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Z C I G IM / X The first three terms—consumption, C, investment, I, and government spending, G—constitute the domestic demand for goods. Until now, we have only looked at C + I + G. But now we have to make two adjustments: First, we must subtract imports. Second, we must add exports. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 2 of 33 19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy The Determinants of C, I, and G Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Domestic Demand: C I G C(Y T ) I (Y , r ) G ( + ) (+,-) The real exchange rate affects the composition of consumption and investment, but not the overall level of these aggregates. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 3 of 33 19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy The Determinants of Imports Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy A higher real exchange rate leads to higher imports, thus: IM IM (Y , ) ( , ) An increase in domestic income, Y, leads to an increase in imports. An increase in the real exchange rate, increase in imports, IM. , leads to an Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 4 of 33 19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy The Determinants of Exports Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Let Y* denote foreign income, thus for exports we write: X X (Y * , ) ( , ) An increase in foreign income, Y*, leads to an increase in exports. An increase in the real exchange rate, decrease in exports. , leads to a Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 5 of 33 19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy Putting the Components Together Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Figure 19 – 1 The Demand for Domestic Goods and Net Exports The domestic demand for goods is an increasing function of income (output). (Panel a) The demand for domestic goods is obtained by subtracting the value of imports from domestic demand, and then adding exports. (Panel b) Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 6 of 33 19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy Putting the Components Together Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Figure 19 – 1 The Demand for Domestic Goods and Net Exports The demand for domestic goods is obtained by subtracting the value of imports from domestic demand, and then adding exports. (Panel c) The trade balance is a decreasing function of output. (Panel d) Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 7 of 33 19-1 The IS Relation in an Open Economy Putting the Components Together Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy We can establish two facts about line AA, which will be useful later in the chapter: AA is flatter than DD. As income increases, the domestic demand for domestic goods increases less than total domestic demand. As long as some of the additional demand falls on domestic goods, AA has a positive slope. YTB is the value of output that corresponds to a trade balance. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 8 of 33 19-2 Equilibrium Output and the Trade Balance Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy The goods market is in equilibrium when domestic output equals the demand – both domestic and foreign – for domestic goods: Y Z Collecting the relations we derived for the components of the demand for domestic goods, Z, we get: Y C Y T I Y , r G IM Y , / X Y *, Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 9 of 33 19-2 Equilibrium Output and the Trade Balance Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Figure 19 – 2 Equilibrium Output and Net Exports The goods market is in equilibrium when domestic output is equal to the demand for domestic goods. At the equilibrium level of output, the trade balance may show a deficit or a surplus. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 10 of 33 19-3 Increases in Demand, Domestic or Foreign Increases in Domestic Demand Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Figure 19 – 3 The Effects of an Increase in Government Spending An increase in government spending leads to an increase in output and to a trade deficit. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 11 of 33 19-3 Increases in Demand, Domestic or Foreign Increases in Domestic Demand Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy There are two important difference you should note between open and closed economies: There is now an effect on the trade balance. The increase in output from Y to Y’ leads to a trade deficit equal to BC. Imports go up, and exports do not change. Government spending on output is smaller than it would be in a closed economy. This means the multiplier is smaller in the open economy. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 12 of 33 19-3 Increases in Demand, Domestic or Foreign Increases in Foreign Demand Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Figure 19 – 4 The Effects of an Increase in Foreign Demand An increase in foreign demand leads to an increase in output and to a trade surplus. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 13 of 33 19-3 Increases in Demand, Domestic or Foreign Increases in Foreign Demand Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy The direct effect of the increase in foreign output is an increase in U.S. exports by some amount, which we shall denote by X : For a given level of output, this increase in exports leads to an increase in the demand for U.S. goods by X , so the line shifts by X from ZZ to ZZ’. For a given level of output, net exports go up by X . So the line showing net exports as a function of output in Panel (b) also shifts up by X , from NX to NX’. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 14 of 33 19-3 Increases in Demand, Domestic or Foreign Fiscal Policy Revisited Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy We have derived two basic results so far: An increase in domestic demand leads to an increase in domestic output, but leads also to a deterioration of the trade balance. An increase in foreign demand leads to an increase in domestic output and an improvement in the trade balance. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 15 of 33 19-3 Increases in Demand, Domestic or Foreign Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Fiscal Policy Revisited The so-called G7 – the seven major countries of the world – meet regularly to discuss their economic situation; the communiqué at the end of the meeting rarely fails to mention coordination. The fact is that there is very limited macrocoordination among countries. Here’s why: Some countries might have to do more than others and may not want to do so. Countries have a strong incentive to promise to coordinate, and then not deliver on that promise. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 16 of 33 19-4 Depreciation, the Trade Balance, and Output Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Recall that the real exchange rate is given by : EP P * In words: The real exchange rate, , is equal to the nominal exchange rate, E, times the domestic price level, P, divided by the foreign price level, P*. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 17 of 33 19-4 Depreciation, the Trade Balance, and Output Depreciation and the Trade Balance: The Marshall–Lerner Condition NX X (Y , ) IM (Y , ) / Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy As the real exchange rate enters the right side of the equation in three places, this makes it clear that the real depreciation affects the trade balance through three separate channels: Exports, X, increase. Imports, IM, decrease The relative price of foreign goods in terms of domestic goods, 1/e, increases. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 18 of 33 19-4 Depreciation, the Trade Balance, and Output Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Depreciation and the Trade Balance: The Marshall–Lerner Condition The Marshall-Lerner condition is the condition under which a real depreciation (a decrease in ) leads to an increase in net exports. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 19 of 33 19-4 Depreciation, the Trade Balance, and Output Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy The Effects of a Depreciation Let’s summarize: The depreciation leads to a shift in demand, both foreign and domestic, toward domestic goods. This shift in demand leads in turn to both an increase in domestic output and an improvement in the trade balance. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 20 of 33 19-4 Depreciation, the Trade Balance, and Output Combining Exchange Rate and Fiscal Policies Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Figure 19 – 5 Reducing the Trade Deficit without Changing output To reduce the trade deficit without changing output, the government must both achieve a depreciation and decrease government spending. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 21 of 33 19-4 Depreciation, the Trade Balance, and Output Combining Exchange Rate and Fiscal Policies Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy If the government wants to eliminate the trade deficit without changing output, it must do two things: It must achieve a depreciation sufficient to eliminate the trade deficit at the initial level of output. The government must reduce government spending. Table 19-1 Initial Conditions Exchange-Rate and Fiscal Policy Combinations Trade Surplus Trade Deficit Low output ?G G? High output G? ?G Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 22 of 33 19-5 Looking at Dynamics: The J-Curve Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy A depreciation may lead to an initial deterioration of the trade balance; increases, but neither X nor IM adjusts very much initially. Eventually, exports and imports respond, and depreciation leads to an improvement of the trade balance. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 23 of 33 19-5 Looking at Dynamics: The J-Curve Figure 19 – 6 Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy The J-Curve A real depreciation leads initially to a deterioration and then to an improvement of the trade balance. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 24 of 33 19-5 Looking at Dynamics: The J-Curve Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Figure 19 – 7 The Real Exchange Rate and the Ratio of the Trade Deficit to GDP: United States, 1980 to 1990 The real appreciation and depreciation of the dollar in the 1980s were reflected in increasing and then decreasing trade deficits. There were, however, substantial lags in the effects of the real exchange rate on the trade balance. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 25 of 33 Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy 19-5 Looking at Dynamics: The J-Curve Figure 19-7 plots the U.S. trade deficit against the U.S. real exchange rate in the 1980s. Turning to the trade deficit, which is expressed as a ratio to GDP, two facts are clear: 1. Movements in the real exchange rate were reflected in parallel movements in net exports. 2. There were substantial lags in the response of the trade balance to changes in the real exchange rate. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 26 of 33 19-6 Saving, Investment, and the Trade Balance Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy The alternative way of looking at equilibrium from the condition that investment equals saving has an important meaning: Y C I G IM / X Subtract C + T from both sides and use the fact that private saving is given by S = Y – C – T to get S I G T IM / X Use the definition of net exports, NX X IM/ , and reorganize, to get: NX S (T G) I Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 27 of 33 19-6 Saving, Investment, and the Trade Balance NX S (T G) I Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy From the equation above, we conclude: An increase in investment must be reflected in either an increase in private saving or public saving, or in a deterioration of the trade balance. An increase in the budget deficit must be reflected in an increase in either private saving, or a decrease in investment, or a deterioration of the trade balance. A country with a high saving rate must have either a high investment rate or a large trade surplus. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 28 of 33 The U.S. Trade Deficit: Origins and Implications Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy Table 1 Average Annual Growth Rates in the United States, the European Union, and Japan since 1991 (percent per year) 1991 to 1995 1996 to 2000 2001 to 2003 United States 2.5 4.1 3.4 European Union 2.1 2.6 1.6 Japan 1.5 1.5 1.6 Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 29 of 33 Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy The U.S. Trade Deficit: Origins and Implications Figure 1 U.S. Net Saving and Net Investment since 1996 (percent of GDP) Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 30 of 33 The U.S. Trade Deficit: Origins and Implications Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy What Happens Next? There are three implications: The U.S. trade and current account deficits will decline in the future. This decline is unlikely to happen without a real depreciation. Most likely, this depreciation will take place when foreign investors become reluctant to lend to the United States at the rate of $800 billion or so per year. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 31 of 33 Key Terms demand for domestic goods Chapter 19: The Goods Market in an Open Economy domestic demand for goods coordination, G-7 Marshall-Lerner condition J-curve Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall • Macroeconomics, 5/e • Olivier Blanchard 32 of 33