* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Getting Oriented with Maps

Astrobiology wikipedia , lookup

Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam wikipedia , lookup

Geocentric model wikipedia , lookup

Rare Earth hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Timeline of astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Extraterrestrial life wikipedia , lookup

Comparative planetary science wikipedia , lookup

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems wikipedia , lookup

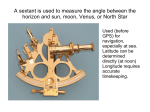

Getting Oriented with Maps Maps are useful for finding our way around; to an Earth Systems Scientist, they are Models of our Planet. Compass Orientation North is a direction parallel to Earth’s Axis and in the direction of Star Polaris The Compass • North is often (but not always) oriented as up on a map. Moving clockwise at ninety degree angles are East, South, and West. Intermediate angles are North-East, or North-North-East, etc. • For greater position, directions are described using angles, with North as Zero Degrees. We will practice this with a worksheet. Magnetic Declination • A magnetic compass’s needle orients toward the Earth’s north magnetic pole. • The Magnetic Pole is not at the same place as the True North pole. • At different places on Earth, a magnetic compass will deviate from true north. This is shown on topographic maps. Here, it is about 4.5 degrees. Coordinate Systems • For small land areas a grid system is simple and easy to understand. • A football field is a partial grid, in fact it is called a “gridiron” • The city of Washington DC was designed as a grid by Pierre L’Enfant. It is very much like a Cartesian graph in algebra class, with the addition of avenues. ve Problems with Grid Maps • If your city isn’t built on a swamp, there may be hills, or streams to get around. • At some scale, the world gets too big for a flat grid to fit it. • At sea, what do you use for reference to mark the corners? Getting Around “On the Ball” A Spherical Planet has no corners, but if it is spinning we can define some key places; The Poles – the Rotational Axis passes through them. In our solar system, North is defined by the “right hand rule” – wrap your fingers in the direction of spin, your thumb points north The Equator – Extend a plane perpendicular to the axis halfway between the poles. The Equator • Imagine someone standing at the center of a hollow Earth. If they looked straight out from the axis at the center, and turned around, their eyes would be following the equator. • Using a neat model, with a turning “Earth”, your instructor will show how an Equatorial line can be constructed. Parallels of Latitude • Lines of latitude are generated the same way as the Equator, but are north or south of it. • The angular measurement from the center of the earth to the new line is its latitude, measured in degrees (and minutes and seconds if we are getting precise). • Latitude lines are parallel, but only the Equator is a Great Circle; the others all have less circumference. DMS • Just as we used the DMS system to locate stars and planets in astronomy, angles are broken down. • A full circle is 360 degrees (in latitude, we only go north or south by 90 degrees – past that you are going around the other side) • 1 degree = 60 minutes (60’) • 1 minute = 60 seconds (60”) P) RASC Calgary Centre - Latitude and Longitude By: Larry McNish Page last updated August 28, 2005 The Shape of the Earth The Earth is not a Sphere - it is an "Oblate Spheroid" - it is 134.397 Km further around the Equator than it is around the Poles. The following diagram is exaggerated to show what we mean. (The blue line is a circle. 1/3 6378.14 Km (3963.19 miles) 6356.75 Km (3949.90 miles) 6371.00 Km (3958.76 miles) (99.66 % of the Equatorial radius) facweb.bhc.edu/academics/science /harwoodr/GEOG101/Study/LongL at.htm • Here is a nice link if we can follow it Determination of Latitude • A sextant in an instrument for determining latitude. In the northern hemisphere you take a sighting of Star Polaris (the North Star) and measure the angle between in and a vertical (a string tied to a weight). • Your instructor has a simple instrument to show you how this is done (demonstrate). The Problem of Longitude • The other coordinate for location is longitude. Longitudes, or Meridians, are all great circles which pass through both poles. • Longitudes are also measured in degrees, from 0-180, east or west of…What? • There is no obvious reference as there is with the equator. The Longitude Problem, continued. • There is a certain prestige to be the starting point for all maps. • Observatories were the starting points because they had the equipment to make the measurements. • The US Naval Observatory in Foggy Bottom, The Royal Greenwich Observatory outside of London England, and The Paris Observatory in France, all wanted the honor. The Problem of Longitude, III • Longitude is also tied in to time of day. Once it was realized that ships would change days crossing the 180 degree meridian, the world finally settled on the Greenwich Observatory as the Prime Meridian, although French maps did not accept this until 1923. The “line states” of the US western territories were based on the Naval Observatory’s meridian. Another Longitude Problem • Accurate determination of longitude requires knowing what time an observation is made. If you measure the time the sun is most directly overhead, your local noon can be compared to correct time to determine longitude. • At sea, a pendulum clock is unreliable because the ship rocks. • Tables of moons transiting planets will work, if you can wait to make the measurement exactly as they are eclipsed and the sky is clear. The Longitude Problem Solved William Harrison, a clever English man, was an extraordinary clockmaker. Since he was not formally educated, he faced great hurdles and ruined his health but ultimately was awarded a huge prize by the British Royal Society for developing a chronometer which worked at sea. One of the main jobs of the US Naval Observatory was making sure chronometers ran correctly. Time and Date on Earth • Local noon used to be good enough. The US railroad industry had to syncronize railroad timepieces to avoid collisions on shared rail lines. • Today the world is divided into 24 time zones. Each keeps the same minutes. The hours change. Official time (“Zulu”, or GMT, or UCT, is based on Greenwich. • Each time zone is about 15 degrees apart (360/24 = 15). • The International Date Line is at 180 degrees longitude. The System of Latitude and Longitude • Latitude is specified first, then longitude. • Latitude must be expressed as North or South, and Longitude as East or West; otherwise a pair of numbers could describe four different places. • You live at around 38 deg 28 min North, 78 deg 53 minutes West. • Let’s practice finding latitude and longitude on a flat paper map!