* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Curriculum prepared by Leanne M. Yanni, MD

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Curriculum prepared by Leanne M. Yanni, MD

What is the role of novel medications such as pregabalin in the treatment of chronic pain?

Are there evidence-based specific titration schedules being utilized with these medications?

Chronic pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “pain that persists beyond normal tissue

healing time, which is assumed to be three months.”1 Novel medications are typically effective in neuropathic pain

syndromes. Musculoskeletal pain does not respond to novel medications and unfortunately, there is minimal evidence

supporting their use in lumbosacral radiculopathy, though they are commonly prescribed for this condition. 2 3

Neuropathic pain is defined as: "pain caused by a lesion of the peripheral or central nervous system (or both) manifesting

with sensory signs and symptoms." 4 Patients describe neuropathic pain as sensations of electric shock, burning, cold,

pricking, tingling, and itching.5 Commonly used medical terms to describe patients' symptoms include:

•

Allodynia: pain due to a stimulus which does not normally provoke pain.

•

Dysesthesias: an unpleasant or abnormal sensation whether spontaneous or evoked.

•

Hyperalgesia: an exaggerated or prolonged response to a stimulus which is normally painful.

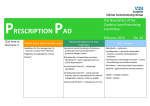

Neuropathic pain guidelines from the International Association for the Study of Pain were published in 2007. The role of

novel medications are clearly outlined in Table 1: Stepwise pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain, which is

adapted to algorithm format below. 2

Factors in medication selection:

•

Co-morbidities

•

Risk: Adverse effect; Drug interactions; Misuse; Overdose

•

Cost

DIAGNOSE

Neuropathic Pain (NP)

•

Assess, diagnosis, treat cause if applicable

•

Identify relevant co-morbidities

•

Establish expectations

INITIATE

•

TCA (nortriptyline, desipramine) or

•

SSNRI (duloxetine, venlafaxine) or

•

Calcium channel alpha-2 delta ligand (gabapentin, pregabalin)

If localized: topical lidocaine alone or in combination

EVALUATE

Substantial pain relief

Partial pain relief

No or inadequate pain relief

Failure of first-line medications

INITIATE

Opioid analgesics or tramadol if:

•

acute neuropathic pain

•

neuropathic cancer pain

•

episodic exacerbations of severe pain

REMEDIATE

→

→

→

→

→

CONTINUE

ADD ANOTHER FIRST-LINE MEDICATION

SWITCH TO ALTERNATIVE FIRST-LINE MEDICATION

SECOND- and THIRD-LINE MEDICATIONS

REFERRAL

PEARL

Only 40-60% of patients will get even

partial pain relief.{{1017 Dworkin,R.H.

2007; }}

1

Tri-cyclic anti-depressants (TCAs)

• Amitriptyline (tertiary amine)

• Imipramine (tertiary amine)

• Doxepin (tertiary amine)

• Desipramine (secondary amine)

• Nortriptyline (secondary amine)

• Cyclobenzaprine (skeletal muscle relaxant; structural

difference from TCAs is only slight, shares side effect

profile)

“Medications that have demonstrated

efficacy in several different NP

conditions may have the greatest

probability of being efficacious in

additional, as yet unstudied

conditions.”{{1017 Dworkin,R.H.

2007; }}

FDA: Cyclobenzaprine is FDA approved for muscle spasm in acute painful musculoskeletal conditions.

MECHANISM: Inhibition of both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake.

EVIDENCE: Multiple randomized trials have shown TCA efficacy in neuropathic pain syndromes. In particular TCAs are

effective in diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) and post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), central post-stroke pain, and postmastectomy pain.6, 7 Amitriptyline and cyclobenzaprine have been effective for fibromyalgia.8, 9 Though not strong,

there is some evidence that TCAs may be effective in chronic low back pain with or without radiculopathy.10

NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT (NNT): For TCAs, NNT is among the lowest

of the medications for neuropathic pain at about 3. However, number needed to

harm (NNH) is about 14. 6

DOSING and TITRATION: All TCAs are dosed the same with the exception

of cyclobenzaprine. TCAs should be started at low doses (10-25mg) and slowly

titrated (every 3-7 days) to minimize adverse effects.2 The lower dose range is

appropriate for elderly and those on medications that pose potential drug

interactions.11 The dose may be increased to a maximal dose of 100-150mg/day.

TCAs are one of the few medications where blood levels can be monitored.

Cyclobenzaprine has immediate release (IR) and extended release (ER)

formulations. Recommended IR dosing is 5mg three times daily with increase to

10mg three times daily. ER dosing is 15mg once daily with increase to 30mg

daily.

Number needed to treat (NNT)

The number of patients needed to

treat to achieve 50% pain relief in 1

patient. NNT may be falsely low if

negative trials are not published.

Number needed to harm (NNH)

The number of patients treated to

affect 1 patient’s study withdrawal

from adverse effects. A medication

with a HIGHER NNH has a lower

adverse effect profile.

ADEQUATE TRIAL: 6-8 weeks with at least 2 weeks at maximum tolerated dose.

NOTE: TCAs are metabolized through CYP450 2D6: about 7-10% of Caucasians are poor metabolizers of drugs through

CYP450 2D6 because of reduced enzyme activity (debrisoquin hydroxylase). This can result in higher than expected

plasma concentrations of TCAs. Drugs that inhibit CYP450 2D6 such as SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine) can also

increase TCA plasma levels.

ADVERSE EFFECTS: TCA H1 histamine blockade causes sedation and weight gain; TCA alpha-1 adrenergic blockade

causes orthostasis; TCA muscarinic blockade causes anti-cholinergic side effects including dry mouth, constipation, urinary

retention and can affect angle-closure glaucoma. Cardiac effects result from inhibition of cardiac fast sodium channels. 12 13

TCAs may also lower seizure thresholds. Amitriptyline and imipramine are tertiary amines with higher affinity than

secondary amines (nortriptyline and desipramine) to the receptors that produce adverse effects.14

COST: 30 day supply at starting dose (www.drugstore.com)

Amitriptyline $3.99; Imipramine $14.99; Nortriptyline $12.99; Desipramine $10.49; Cyclobenzaprine IR $13.99;

Cyclobenzaprine ER $257.99

WalMart 4$ generic available: Amitriptyline; Doxepin; Nortriptyline; Cyclobenzaprine IR

Bottom line

TCAs are effective, easy to dose and low in cost but their adverse effect profile often limits use,

particularly in patients with comorbidities and polypharmacy.

2

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

• Duloxetine (Cymbalta®); Milnacipran (Savella®); Venlafaxine (Effexor®)

FDA: Duloxetine is FDA approved for diabetic peripheral neuropathy and fibromyalgia. Milnacipran is FDA approved for

fibromyalgia.

MECHANISM: Inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. Specifically, milnacipran has about 3 times greater

inhibition of norepinephrine than serotonin. Venlafaxine inhibits serotonin reuptake at lower doses and both serotonin and

norepinephrine reuptake at higher doses. It also has some inhibition of dopamine reuptake.

EVIDENCE: Three randomized trials have shown efficacy of duloxetine over placebo in treating diabetic peripheral

neuropathy (DPN).15-18 As a result of at least 3 randomized trials duloxetine also received approval for fibromyalgia. 19-22

Milnacipran versus placebo has been studied in fibromyalgia23, 24 : the largest trial was 15 weeks and included over 1000

patients. Pain reduction was seen by the end of week 1 and sustained through week 15.25 A recently published 27-week

trial showed milnacipran was better than placebo for achieving a 30% pain reduction and improvement in global wellbeing.26 Venlafaxine has shown efficacy in treating peripheral neuropathy including DPN.27 One randomized trial has

shown that venlafaxine may be as effective as imipramine in treating DPN.28 However, inconsistent or negative results

have been reported for other neuropathic pain syndromes. Venlafaxine has recently been studied in tension-type headache

at a dose of 150mg/day.29

NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT: Overall, SNRIs have an NNT as low as 4 but average is between 5 and 6 in neuropathic

pain with an inappreciable NNH.6, 30

DOSING and TITRATION: Duloxetine: Initial dose is 30mg daily for 7 days then increase to 60mg daily. At doses of

60mg/day and above, it can be administered twice daily. Similar effectiveness has been shown for daily doses of 60mg and

120mg, with fewer adverse effects at the 60mg dose.15 31

Milnacipran has specific titration recommendations. The

Milnacipran Dosing and Titration

maximum dose is 200mg/day though this was no more effective

Day 1: 12.5mg once

than 100mg/day.26 While no dose adjustments are needed for

Day 2-3: 12.5mg twice daily (25mg/day)

hepatic impairment, dose adjustments are needed for renal

Day 4-7: 25mg twice daily (50mg/day)

impairment (CrCl:5-29mL/min) and it is not recommended for

Day 7+: 50mg twice daily (100mg/day)

end-stage renal disease.

Venlafaxine has two formulations: immediate release (IR) and

extended release (XR). The dosing for the IR formulation is the same total daily dose as the ER formulation, though given

twice daily. The XR formulation should be initiated at 75mg/day and increased by 75mg every 7 days to an efficacious

dose, typically 150mg/day to 225mg/day.27 The maximum dose is 300mg/day.

ADEQUATE TRIAL: Treatment response should be assessed after 4 weeks at the efficacious dose (duloxetine 60mg/day,

milnacipran 100mg/day, venlafaxine 150-225mg/day).

ADVERSE EFFECTS: SNRIs in general have gastrointestinal side effects and can cause somnolence. While Duloxetine

has no appreciable cardiovascular effects, milnacipran can raise blood pressure and heart rate secondary to its

disproportionate norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. Along with raising blood pressure, some cardiac risk has been

associated with the use of venlafaxine XR at doses >150mg/day.27

COST: 30 day supply at starting dose (www.drugstore.com)

Duloxetine: $131.39; Milnacipran: No cost information available (expected March 2009); Venlafaxine: IR $107.99 and

XR $115.33

Bottom line

SNRIs are effective, well-tolerated, and FDA-approved for several conditions

but are still high in cost.

3

Anticonvulsants

• Gabapentin (Neurontin®), Pregabalin (Lyrica®)

FDA: Gabapentin is FDA approved for post-herpetic

neuralgia. Pregabalin is FDA approved for diabetic

peripheral neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and

fibromyalgia.

TOP LINE

With gabapentin’s safety profile and lack of drug

interactions, there is no reason (other than cost) NOT

to try this medication in a neuropathic pain condition

as a first-line agent.

MECHANISM: Though gabapentin is structurally similar to the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), it

does not interact with GABA receptors or neurons. Its analgesic effect may be from modulation of voltage-gated calcium

channels (alpha-2-delta subunit), with a subsequent effect on the concentrations of glutamate, norepinephrine and substance

P.32 Pregabalin has the same effect but also reduces excitatory neurotransmitter release.33

EVIDENCE:

Randomized trials have proven efficacy of gabapentin in a variety of neuropathic pain states including diabetic peripheral

neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and trigeminal neuralgia.34-37 Gabapentin appears to

be as effective as amitriptyline for DPN and as effective as nortriptyline for post-herpetic neuralgia with fewer side

effects in comparison to both of these TCAs.35, 38 At doses of 1200mg-2400mg/day, gabapentin may be effective in the

treatment of fibromyalgia.39 Additionally, at a dose of 2400mg/day it may be a choice for migraine prophylaxis.40

Gabapentin has been studied in combination with venlafaxine and morphine for neuropathic pain and has shown efficacy

in combination therapy.41, 42 The data on gabapentin in radicular pain is minimal and disappointing.10

Randomized trials have shown effectiveness of pregabalin in diabetic peripheral neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia,

spinal cord injury, and fibromyalgia.43-47 Pregabalin at 600mg/day was more effective than placebo in pain reduction and

improved sleep quality for DPN.48 Effectiveness in pain reduction and improvement in global functioning in over 500

patients with fibromyalgia has been demonstrated with pregabalin doses of 300mg, 450mg, and 600mg/day.49 The

Fibromyalgia Relapse Evaluation and Efficacy for Durability Of Meaningful relief (FREEDOM) trial in over 500 patients

showed that higher doses (300mg, 450mg and 600mg/day) of pregabalin in fibromyalgia were associated with longer times

to loss of therapeutic responses.50

NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT: Together, gabapentin and pregabalin have an NNT of between 4 and 5 for neuropathic

pain conditions, though gabapentin may have an NNT of as low as 3 if lower doses are excluded (<900mg/day is not

effective).6, 30 51 The NNH for gabapentin is reported above 25 while pregabalin is reported as low as 11.6

DOSING and TITRATION: Based on several studies and consensus recommendations a dosing recommendation table

for gabapentin is provided.2, 52 Lower doses and slower titration schedules are recommended for elderly, high risk patients

(poor general health, low body weight) and patients with CrCl<60mL/min. Maximum dosage is 3600mg/day. Pregabalin

can be initiated at 50mg three times daily or 75mg twice daily for a total dose of 150mg/day. In 7 days this can be increased

to 150mg twice daily. Further titration can occur if sufficient pain relief does not occur after 2-4 weeks and few or no

adverse effects are experienced. The maximum beneficial dose in patients with DPN has been 300mg/day and with

fibromyalgia has been 600mg/day.50 A recent study in PHN, shows that flexible dosing between 150mg and 600mg/day

can be effective.53

ADEQUATE TRIAL: For gabapentin, efficacy may occur as

early as the 2nd week of therapy, with full therapeutic response

approximately 2 weeks after a therapeutic dose is achieved,

though it may take 3-8 weeks to achieve the therapeutic dose.

For pregabalin, 4 weeks at maximally tolerated dose is an

adequate trial.

BOTTOM LINE

Gabapentin and pregabalin have similar

effectiveness in NP but pregabalin is much easier to

dose. There are no significant drug interactions with

either medication, though both need dose adjustment

in renal insufficiency. Pregabalin’s drawback is cost

and greater adverse effect profile when compared

with gabapentin.

ADVERSE EFFECTS: Neither gabapentin nor pregabalin

have significant drug interactions. Adverse effects include

dizziness, somnolence, dry mouth, blurred vision, peripheral edema, weight gain, and abnormal thinking.

COST: 30 day supply at starting dose (www.drugstore.com)

Gabapentin: generic $19.99; brand $58.42; Pregabalin: $212.84

4

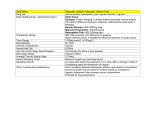

TABLE: Gabapentin Dosing and Titration*

Recommended

Schedule

Dosing

Initiation

Doses should be initiated at bedtime due to the sedating properties of gabapentin.

Initiate 300mg QHS titrated in 300mg increments every 3-7 days as tolerated until 900mg QHS is reached.

Doses >900mg/day may be divided BID-TID.

Target effective dose is 1800mg/day.

Example titration schedule:

Titration

•

Days 1-3: 300mg QHS

•

Days 4-6: 600mg QHS

•

Days 7-9: 900mg QHS

Dose should be titrated in 300mg increments every 3-7 days to achieve optimal efficacy and tolerability.

•

Maintenance

Dose should be individualized to achieve maximal efficacy and tolerability.

•

Initiation in

elderly,

sensitive

patients and

those with renal

insufficiency

Days 7-21: 900-1800mg/day in divided doses

Days 21+: 1800-3600mg/day in divided doses

Initiate 100mg QHS titrated in 100mg increments every 7-14 days as tolerated until 600mg QHS is reached.

Doses should be initiated at bedtime due to the sedating properties of gabapentin.

Doses >600mg/day may be divided BID-TID.

*Adapted from VCU Pain Management: An Online Curriculum. Available at www.paineducation.vcu.edu. Accessed February 20, 2009.

Tramadol (Ultram® and Ultram ER®)

FDA: Tramadol is approved for the relief of moderate to moderately-severe acute and chronic pain.

MECHANISM: Tramadol is a µ receptor agonist (affinity is 1/10th that of codeine) and it also weakly inhibits

norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, similar to TCAs and SNRIs.

EVIDENCE: A 2004 Cochrane review concluded that “tramadol is an effective treatment for neuropathic pain.”54

Tramadol has shown effectiveness in treating both diabetic peripheral neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia.55, 56 Its

effectiveness in the treatment of fibromyalgia has also been demonstrated 57 58 Of the “novel medications,” tramadol is the

only one with evidence of effectiveness in low back pain and osteoarthritis.59, 60 It was moderately more effective than

placebo for short-term pain and functional status after 4 weeks. 61

NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT: Tramadol has a NNT of about 4 for neuropathic pain conditions and a NNH of 9.6

DOSING AND TITRATION: Tramadol has both an immediate

Tramadol IR Dosing and Titration

release (IR) and extended release (ER) formulation. Initial

Day 1-3 50mg once a day

Day 4-6 50mg twice a day

Tramadol IR dosing is recommended at 50mg once or twice daily.

Day 7-10 50mg three times a day

This can be increased by 50mg-100mg in divided doses every 3

Day 11-14 50mg four times per day

days. A maintenance IR dose is 50 to 100mg 4 times daily. The

Increase as tolerated every 3 days to maximum of

maximum dose is 400mg/day (elderly; maximum dose is

400mg/day (300mg/day in elderly)

300mg/day). Tramadol ER dosing is 100mg once daily, titrated

62

every 5 days to a maximum of 300mg once daily. Tramadol is metabolized by CYP450 enzymes and excreted by the

kidneys making dose adjustment necessary in both hepatic and renal insufficiency.

ADEQUATE TRIAL: An adequate trial at the highest tolerated dose is 4 weeks.

ADVERSE EFFECTS: Common side effects include dizziness, nausea, constipation, somnolence, and orthostatic

hypotension. Tramadol reduces the seizure threshold and because this medication inhibits serotonin reuptake, it must be

used cautiously with agents that have the same mechanism (TCAs, SSRIs, SNRIs, MAOIs).

COST: 30 day supply at starting dose (www.drugstore.com) Tramadol: $47.97; Tramadol extended release: $118.79;

Tramadol with acetaminophen: generic $27.99; brand $54.32

5

PEARL

If there is focal allodynia, prescribe lidocaine.

Lidocaine Patch 5% (Lidoderm®)

FDA: The lidocaine patch 5% is FDA approved for allodynia and postherpetic neuralgia.

MECHANISM: Topical anesthetic.

EVIDENCE: The lidocaine patch 5% is currently FDA approved for the treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia though it has

demonstrated effectiveness in other neuropathic pain syndromes, particularly in those with allodynia. These include DPN,

CRPS, neuroma, meralgia parethetica, intercostal neuralgia, radiculopathy, post-thoracotomy pain and post-mastectomy

pain.63, 64 65

NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT: Lidocaine patch 5% as add-on therapy reduced ongoing pain and allodynia with a NNT

between 4 and 5.6

DOSING and TITRATION: A 12 hour on, 12 hour off dosing schedule allows effective pain control with unappreciable

blood levels and no accumulation. No more than 3 patches/12 hours are applied to the area of maximal pain. If the

lidocaine patch 5% cannot be obtained, topical lidocaine preparations should be considered.

ADEQUATE TRIAL: 3 weeks.2

ADVERSE EFFECTS: Mild skin reactions may occur but otherwise the patches are well tolerated and very safe.66 Special

consideration before use should be given to patients on oral Class I anti-arrhythmic agents such as mexiletine or in patients

with severe hepatic dysfunction.

COST: 30 day supply at starting dose (www.drugstore.com)

Lidocaine patch 5%: $206.47 for 30 patches; Topical lidocaine preparations come as cream, gel, lotion, ointment, pad,

spray, topical and viscous solutions in variable strengths from 0.5% to 5%. It is available in generic and brand formulations.

Check with local pharmacy when prescribing.

Topical Diclofenac

• Diclofenac 1% gel (Voltaren Gel®) and diclofenac epolamine 1.3% patch (Flector®)

FDA: Diclofenac 1% gel is approved for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Diclofenac 1.3% patch is approved for the treatment of pain due to minor strains,

sprains, and contusions.

MECHANISM: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with inhibition of

prostaglandin synthesis. A local tissue reservoir develops underneath the patch to

provide anti-inflammatory effects.

Topical Diclofenac

Potential use in chronic pain

may be for short-term flares

of osteoarthritis of a specific

joint(s) and/or short-term

treatment of an area of focal

tissue inflammation.

EVIDENCE: In focal areas of osteoarthritis (hands and knee) diclofenac 1% gel was more effective than placebo in

reducing pain scores in 2 trials; 6 weeks and 12 weeks in duration. However, there has also been negative unpublished

studies. 67 Similarly, for diclofenac 1.3% patch there have been mixed results, though at least 2 positive studies show

reduction in pain scores via the Visual Analog Scale. 68 There are no comparison studies of diclofenac 1% gel or

diclofenac 1.3% patch with other treatments for acute musculoskeletal pain. Neither formulation has been studied in

chronic pain.

Answer 1b: DOSING and TITRATION:

Diclofenac 1% gel: Application to upper extremity joints (hands, elbows, wrists) is recommended to be 2 grams (measured

by a dosing card) four times daily with no more than 8 grams applied to any one joint in 24 hours. Application to lower

extremity joints (knees, ankles, feet) is recommended to be 4 grams four times daily with no more than 16 grams applied to

any one joint in 24 hours. Patients should not swim, bathe, or shower for at least 1 hour after application. The maximum 24

hour total application dose is 32 grams. Diclofenac 1.3% patch: One patch should be applied to the affected area twice

daily. Pain reduction is expected to occur about 1-3 hours after patch application.

ADEQUATE TRIAL: Within 3 days of twice daily application, a steady state blood level is reached albeit at very low

doses.

6

ADVERSE EFFECTS: Application site reaction occurs in about 7% of patients with diclofenac 1% gel. Pruritis,

dermatitis, and burning have occurred at the site of application from the diclofenac 1.3% patch. There are no systemic

effects reported from application of the gel or the patch.

COST: (www.drugstore.com)

Diclofenac 1% gel, 100 gram tube: $34.46 (approximately 7 day supply if applied to lower extremity and approximately 14

day supply if applied to upper extremity at recommended dosages); Diclofenac 1.3% patch: $155.99 for 30 patches,

approximately $5.20 per patch

REFERENCES

1. Merskey H, Bogduk N, eds. Classification of Chronic Pain. Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of

Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, Washington: IASP Press; 1994.

2. Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence-based

recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237-251.

3. Khoromi S, Cui L, Nackers L, Max MB. Morphine, nortriptyline and their combination vs. placebo in patients with

chronic lumbar root pain. Pain. 2007;130:66-75.

4. Dworkin RH, Backonja M, Rowbotham MC, et al. Advances in neuropathic pain: Diagnosis, mechanisms, and treatment

recommendations. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1524-1534.

5. Boureau F, Doubrere JF, Luu M. Study of verbal description in neuropathic pain. Pain. 1990;42:145-152.

6. Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, Jensen TS, Sindrup SH. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: An evidence

based proposal. Pain. 2005.

7. Argoff CE, Backonja MM, Belgrade MJ, et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: Consensus guidelines for treatment.

J Fam Pract. 2006;55:1-20.

8. Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292:2388-2395.

9. Hauser W, Bernardy K, Uceyler N, Sommer C. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants: A metaanalysis. JAMA. 2009;301:198-209.

10. Chou R, Huffman LH, American Pain Society, American College of Physicians. Medications for acute and chronic low

back pain: A review of the evidence for an american pain Society/American college of physicians clinical practice

guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:505-514.

11. AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc.

2002;50:S205-24.

12. Roose SP, Laghrissi-Thode F, Kennedy JS, et al. Comparison of paroxetine and nortriptyline in depressed patients with

ischemic heart disease. JAMA. 1998;279:287-291.

13. Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, Hall K, Murray KT. Cyclic antidepressants and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Clin

Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75:234-241.

14. Watson CP, Vernich L, Chipman M, Reed K. Nortriptyline versus amitriptyline in postherpetic neuralgia: A

randomized trial. Neurology. 1998;51:1166-1171.

15. Wernicke J, Lu Y, D'Souza DN, Waninger A, Tran P. Antidepressants: Duloxetine at doses of 60mg QD and 60mg BID

is effective in treatment of diabetic neuropathic pain (DNP). J Pain. 2004;5:S48.

16. Raskin J, Pritchett YL, Wang F, et al. A double-blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo

in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6:346-356.

17. Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, Lee TC, Iyengar S. Duloxetine vs. placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy.

Pain. 2005;116:109-118.

18. Wernicke JF, Pritchett YL, D'Souza DN, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine in diabetic peripheral

neuropathic pain. Neurology. 2006;67:1411-1420.

19. Russell IJ, Mease PJ, Smith TR, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or

without major depressive disorder: Results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial.

Pain. 2008;136:432-444.

20. Arnold LM, Pritchett YL, D'Souza DN, Kajdasz DK, Iyengar S, Wernicke JF. Duloxetine for the treatment of

fibromyalgia in women: Pooled results from two randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Womens Health

(Larchmt). 2007;16:1145-1156.

21. Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the

treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain. 2005;119:5-15.

22. Arnold LM, Lu Y, Crofford LJ, et al. A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the

treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorder. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2974-2984.

23. Gendreau RM, Thorn MD, Gendreau JF, et al. Efficacy of milnacipran in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol.

2005;32:1975-1985.

7

24. Vitton O, Gendreau M, Gendreau J, Kranzler J, Rao SG. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of milnacipran in the

treatment of fibromyalgia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19 Suppl 1:S27-35.

25. Clauw DJ, Mease P, Palmer RH, Gendreau RM, Wang Y. Milnacipran for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults: A

15-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2008;30:19882004.

26. Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Gendreau RM, et al. The efficacy and safety of milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. A

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:398-409.

27. Rowbotham MC, Goli V, Kunz NR, Lei D. Venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of painful diabetic

neuropathy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2004;110:697-706.

28. Sindrup SH, Bach FW, Madsen C, Gram LF, Jensen TS. Venlafaxine versus imipramine in painful polyneuropathy: A

randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60:1284-1289.

29. Zissis NP, Harmoussi S, Vlaikidis N, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of venlafaxine XR in

out-patients with tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:315-324.

30. Quilici S, Chancellor J, Lothgren M, et al. Meta-analysis of duloxetine vs. pregabalin and gabapentin in the treatment of

diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:6.

31. Dunner DL, Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH, Watkin JG, Fava M. Clinical consequences of initial duloxetine dosing

strategies:Comparison of 30mg and 60mg QD starting doses. Curr Ther Res. 2005;66:522-40.

32. Field MJ, Hughes J, Singh L. Further evidence for the role of the alpha(2)delta subunit of voltage dependent calcium

channels in models of neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:282-286.

33. The Medical Letter. Pregabalin (lyrica) for neuropathic pain and epilepsy. The Medical letter on drugs and therapeutics.

2005;47:75-77.

34. Backonja M, Beydoun A, Edwards KR, et al. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in

patients with diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1831-1836.

35. Chandra K, Shafiq N, Pandhi P, Gupta S, Malhotra S. Gabapentin versus nortriptyline in post-herpetic neuralgia

patients: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial--the GONIP trial. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;44:358-363.

36. Mellick LB, Mellick GA. Successful treatment of reflex sympathetic dystrophy with gabapentin. Am J Emerg Med.

1995;13:96.

37. Cheshire WP,Jr. Defining the role for gabapentin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: A retrospective study. J Pain.

2002;3:137-142.

38. Morello CM, Leckband SG, Stoner CP, Moorhouse DF, Sahagian GA. Randomized double-blind study comparing the

efficacy of gabapentin with amitriptyline on diabetic peripheral neuropathy pain. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1931-1937.

39. Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, Stanford SB, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1336-1344.

40. Mathew NT, Rapoport A, Saper J, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin in migraine prophylaxis. Headache. 2001;41:119-128.

41. Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Weaver DF, Houlden RL. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for

neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1324-1334.

42. Simpson DA. Gabapentin and venlafaxine for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis.

2001;3:53-62.

43. Lesser H, Sharma U, LaMoreaux L, Poole RM. Pregabalin relieves symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy: A

randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2004;63:2104-2110.

44. Richter RW, Portenoy R, Sharma U, Lamoreaux L, Bockbrader H, Knapp LE. Relief of painful diabetic peripheral

neuropathy with pregabalin: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Pain. 2005;6:253-260.

45. Sabatowski R, Galvez R, Cherry DA, et al. Pregabalin reduces pain and improves sleep and mood disturbances in

patients with post-herpetic neuralgia: Results of a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain. 2004;109:26-35.

46. Vranken JH, Dijkgraaf MG, Kruis MR, van der Vegt MH, Hollmann MW, Heesen M. Pregabalin in patients with

central neuropathic pain: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a flexible-dose regimen. Pain.

2008;136:150-157.

47. Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: Results of a

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1264-1273.

48. Tolle T, Freynhagen R, Versavel M, Trostmann U, Young JP,Jr. Pregabalin for relief of neuropathic pain associated

with diabetic neuropathy: A randomized, double-blind study. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:203-213.

49. Mease PJ, Russell IJ, Arnold LM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of pregabalin in

the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:502-514.

50. Crofford LJ, Mease PJ, Simpson SL, et al. Fibromyalgia relapse evaluation and efficacy for durability of meaningful

relief (FREEDOM): A 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with pregabalin. Pain. 2008;136:419-431.

51. Gorson KC, Schott C, Herman R, Ropper AH, Rand WM. Gabapentin in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy:

A placebo controlled, double blind, crossover trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:251-252.

8

52. Backonja M, Glanzman RL. Gabapentin dosing for neuropathic pain: Evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled

clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2003;25:81-104.

53. Stacey BR, Barrett JA, Whalen E, Phillips KF, Rowbotham MC. Pregabalin for postherpetic neuralgia: Placebocontrolled trial of fixed and flexible dosing regimens on allodynia and time to onset of pain relief. J Pain. 2008;9:10061017.

54. Duhmke RM, Cornblath DD, Hollingshead JR. Tramadol for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2004;(2):CD003726.

55. Sindrup SH, Andersen G, Madsen C, Smith T, Brosen K, Jensen TS. Tramadol relieves pain and allodynia in

polyneuropathy: A randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Pain. 1999;83:85-90.

56. Gobel H, Stadler T. Treatment of post-herpes zoster pain with tramadol. results of an open pilot study versus

clomipramine with or without levomepromazine. Drugs. 1997;53 Suppl 2:34-39.

57. Bennett RM, Kamin M, Karim R, Rosenthal N. Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of

fibromyalgia pain: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med. 2003;114:537-545.

58. Russell IJ, Kamin M, Bennett RM, Schnitzer TJ, Green JA, Katz WA. Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of pain in

fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol. 2000;6:250-257.

59. Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, Valencia L. Tramadol for osteoarthritis: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J

Rheumatol. 2007;34:543-555.

60. Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, Valencia L. Tramadol for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2006;3:CD005522.

61. Schnitzer TJ, Gray WL, Paster RZ, Kamin M. Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of chronic low back pain. J Rheumatol.

2000;27:772-778.

62. Hair PI, Curran MP, Keam SJ. Tramadol extended-release tablets in moderate to moderately severe chronic pain in

adults: Profile report. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:259-263.

63. Barbano RL, Herrmann DN, Hart-Gouleau S, Pennella-Vaughan J, Lodewick PA, Dworkin RH. Effectiveness,

tolerability, and impact on quality of life of the 5% lidocaine patch in diabetic polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:914918.

64. Rowbotham MC, Davies PS, Verkempinck C, Galer BS. Lidocaine patch: Double-blind controlled study of a new

treatment method for post-herpetic neuralgia. Pain. 1996;65:39-44.

65. Devers A, Galer BS. Topical lidocaine patch relieves a variety of neuropathic pain conditions: An open-label study.

Clin J Pain. 2000;16:205-208.

66. Gammaitoni AR, Alvarez NA, Galer BS. Safety and tolerability of the lidocaine patch 5%, a targeted peripheral

analgesic: A review of the literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:111-117.

67. Diclofenac gel for osteoarthritis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2008;50:31-32.

68. A diclofenac patch (flector) for pain. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2008;50:1-2.

9