* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Treatment of Pain in Dercum`s Disease with Lidoderm® (Lidocaine 5

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

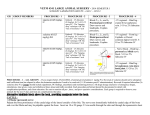

PAIN MEDICINE Volume 9 • Number 8 • 2008 CASE REPORT Treatment of Pain in Dercum’s Disease with Lidoderm® (Lidocaine 5% Patch): A Case Report Mehul J. Desai, MD, MPH,* Radhika Siriki, MD,† and Dajie Wang, MD* *Department of Anesthesiology, Jefferson Pain Center, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; †Department of Internal Medicine, Englewood Hospital, Englewood, New Jersey, USA ABSTRACT Case. A patient with Dercum’s disease successfully treated with transdermal lidocaine 5% patches. The patient’s pain was initially rated as an 8/10. At follow-up examination after 1 month, the patient rated her pain as 3/10—a >60% reduction in pain; this pain reduction persisted at subsequent 1-month follow-up intervals. Conclusion. Current therapeutic options in the treatment of Dercum’s disease have proven either ineffective or cumbersome. The use of transdermal lidocaine is a safe and non-invasive treatment modality that has been efficacious in alternate forms. The use of this medication might prove preferable to more invasive or risky treatment and warrants further investigation. Key Words. Lidocaine; Pain Management; Obesity Introduction D ercum’s disease was first described by neurologist Francis Xavier Dercum in 1892 [1]. Also known as adiposis dolorosa, lipomatosis dolorosa, Ander’s Syndrome, or Dercum–Vitaut syndrome, it is a rare disorder characterized by multiple painful subcutaneous lipomas on the trunk and extremities. Dercum’s disease most commonly occurs in obese, postmenopausal women (female-to-male ratio approximately 30:1) [2]. There is suspicion of an autosomal dominant genetic predisposition to the development of Dercum’s disease [3,4]. Most cases, however, tend to occur sporadically. Although the exact patho- Reprint requests to: Mehul J. Desai, MD, MPH, Jefferson Pain Center, 834 Chestnut Street, Suite T150, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA. Tel: 215-955-7246; Fax: 215-9235086; E-mail: [email protected]. physiology is unknown, it is postulated that the etiology of the disease is related to abnormal blood flow or circulatory dysfunction [5]. Treatment has been challenging due to the rarity of this condition. Here we present a case of a patient successfully treated with lidocaine 5% transdermal patches and briefly review the treatment literature. Case Report A 61-year-old female with medical history of Dercum’s disease, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, rheumatoid arthritis, depression, and migraine headaches presented to our tertiary pain clinic for evaluation. Her medications at presentation included verapamil, nortriptyline, sumatriptan, and gabapentin three times daily, all stable for greater than 6 months. The patient’s complaints included severe pain in the right medial and © American Academy of Pain Medicine 1526-2375/08/$15.00/1224 1224–1226 doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00417.x Downloaded from http://painmedicine.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 24, 2016 Introduction. Dercum’s disease is a rare disorder characterized by multiple painful subcutaneous lipomas on the trunk and extremities. It most commonly occurs in obese, postmenopausal women. The pain associated with this condition is postulated to arise from enlarging lipomas producing pressure on peripheral nerves, thereby initiating pain and sometimes paresthesias. Treatment has been challenging due to the rarity of this condition. Treatment of Pain in Dercum’s Disease posterior thigh and right anterior chest wall. This pain was characterized as constant burning and shooting. The pain was initially rated as an 8/10. Physical examination revealed discrete lipomas at the right anterior chest wall and right posterior and medial thigh. Lidocaine 5% transdermal patches were prescribed and placed over the two painful sites. At follow-up examination after 1 month, the patient rated her pain as 3/10—a >60% reduction in pain; this pain reduction persisted at subsequent 1-month follow-up intervals. Discussion The majority of treatment studies reported in the literature are uncontrolled case reports focusing on medical and surgical interventions. Surgical therapies in the literature include lipoma resection and liposuction. Surgery has demonstrated only partial relief of the pain, with the advent of new painful lesions at nearby locations [5,13]. Medical therapy has consisted of a variety of agents, including analgesics, membranestabilizing agents such as lidocaine and mexiletine, and corticosteroids. Recently, the use of interferon alfa-2b therapy in patients with concurrent hepatitis C was reported to result in long-term pain relief [14]. Systemic steroids and pituitary supplementation have not proven effective. Palmer reported some reduction of pain with different doses of prednisone in a single patient [8]. Reggiani et al. reported successful pain relief with the use of EMLA, a eutectic mixture of lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%, in a patient who previously failed to respond to intravenous lidocaine, oral mexiletine, and intramuscular methylprednisolone therapy [15]. Mexiletine is an analogue of lidocaine that is not metabolized as rapidly as lidocaine and is available in an oral form. Longstanding pain relief after oral treatment with mexiletine has been reported in patients with Dercum’s disease who were previously responsive to intravenous lidocaine therapy [16,17]. Currently, case reports are the largest segment of the literature describing some efficacy with intravenous lidocaine. Lidocaine theoretically blocks impulse conduction in peripheral nerves and depresses cerebral activity, therefore promoting pain relief. One such report stated that 1,300 mg of lidocaine was given daily for 4 days to achieve pain relief for a patient with Dercum’s disease; however, this dosage prompted warnings regarding serious side effects such as cardiac toxicity and seizure activity [18]. Iwane et al. reported pain relief lasting up to 10 hours with intravenous lidocaine doses of 200–400 mg on every-other-day dosing; however, the patient reported euphoria and numbness during infusion, and flushing and altered mental status was noted following treatment [7]. Petersen and Kastrup reported two patients with Dercum’s disease treated with doses from 200–600 mg of lidocaine resulting in 1 week to 25 days of total pain relief over a 2-year period [17]. Atkinson reported 2–12 months of pain relief with lidocaine infusions over a 2-year period [19]. Finally, Devillers and Oranje reported pain-free periods of up to 4 months with lidocaine infusions every 6 months [16]. Unfortunately, this therapy Downloaded from http://painmedicine.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 24, 2016 There are three common subtypes of Dercum’s disease: type I: juxta-articular type, with painful folds of fat on the inside of the knees and/or on the hips, in rare cases only evident in upper-arm fat; type II: diffuse, generalized type, where widespread pain from fatty tissue is found, apart from that of type I, also often in the dorsal upper-arm fat, in the axillary and gluteal fat, in the stomach wall, in dorsal fat folds, and on the soles of the feet; and type III: lipomatosis, nodular type, with intense pain in and around multiple lipomas, sometimes in the absence of general obesity; lipomas are approximately 0.5–4 cm, soft, and attached to the surrounding tissue [6]. This syndrome consists of four cardinal symptoms: 1) multiple, painful, fatty masses; 2) generalized obesity; 3) weakness and fatigability; and 4) mental disturbances, including emotional instability, depression, epilepsy, confusion, and dementia. The typical patient is an obese postmenopausal woman between 40 and 60 years of age with pain that appears out of proportion to physical finding. The pain can last for hours, can be paroxysmal or continuous, and worsens with movement. The condition can also be associated with early congestive heart failure, myxedema, joint pain, paroxysmal flushing episodes, tremors, cyanosis, hypertension, headaches, and epistaxis [1,7–9]. The pain associated with this condition is postulated to arise from enlarging lipomas. These lipomas are thought to produce pressure on peripheral nerves, thereby initiating pain and sometimes paresthesias, although this hypothesis is not universally accepted [10,11]. Other theories include defective lipid metabolism and endocrine abnormalities [10,12]. The neuropathic pain resulting from this condition remains a challenge due to the rarity of this condition and its unclear pathoetiology. Current therapy focuses on symptomatic control and can be either medical or surgical. 1225 1226 Conclusions Current therapeutic options in the treatment of Dercum’s have proven cumbersome or invasive. The use of transdermal lidocaine is a safe and non-invasive treatment modality that has been efficacious in alternate forms. Although the existing data suggest a systemic lidocaine effect, low plasma levels of lidocaine administered by transdermal delivery systems likely necessitate that they be utilized directly at the lesion site. The use of this medication might prove to be useful in a treatment algorithm of Dercum’s disease, particularly early in disease progression. Its use as a first-line agent might prove preferable to more invasive or risky treatments and warrants further investigation, although controlled trials might be challenging given the rarity of this condition. References 1 Dercum FX. Three cases of hitherto unclassified affection resembling in its grosser aspects obesity, but associated with special nervous systems-adiposis dolorosa. Am J Med Sci 1892;104:521–35. 2 Bonatus TJ, Alexander AH. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa). A case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop 1986;205:251–3. 3 Lynch HT, Harlan WL. Hereditary factors in adiposis dolorosa. Am J Hum Genet 1963;15:184–90. 4 Cantu JM, Ruiz-Barquin E, Jiminez M, Castillo L, Macotela-Ruiz E. Autosomal dominant inheritance in adiposis dolorosa (Dercum’s disease). Humangenetik 1973;18:89–91. 5 Held JL, Andrew JA, Kohn SR. Surgical amerlioration of Dercum’s disease: A report and review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1989;15(12):1294–6. 6 Campen RB, Sang CN, Duncan LM. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 252006. A 41-year-old woman with painful subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med 2006;355(7):714–22. 7 Iwane T, Maruyama M, Matsuki M, Ito Y, Shimoji K. Management of intractable pain in adiposis dolorosa with intravenous administration of lidocaine. Anesth Analg 1976;55(2):257–9. 8 Palmer ED. Dercum’s disease: Adiposis dolorosa. Am Fam Physician 1981;24(5):155–7. 9 Defranzo AJ, John M. Adiposis dolorosa (Dercum’s disease): Lioposuction as an effective form of treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990;85(2):289– 92. 10 Dercum FX, McCarthy DJ. Autopsy in case of adiposis dolorosa. Am J Med Sci 1902;124:994– 1007. 11 Mella BA. Adiposis dolorosa. J Univ Mich Med Cent 1967;32(2):79. 12 Blomstrand R, Juhlin L, Nordenstam R, Ohlsson B, Engstrom J. Adiposis dolorosa associated with defects in lipid metabolism. Acta Derm Venereol 1971;51(4):243–50. 13 Amine B, Leguilchard F, Benhamou CL. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): A new case report. Joint Bone Spine 2004;71(2):147–9. 14 Gonciarz Z, Mazur W, Hartleb J, et al. Interferon alfa-2b induced long-term relief of pain in two patients with adiposis dolorosa and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 1997;27(6):1141. 15 Reggiani M, Errani A, Staffa M, Schianchi S. Is EMLA effective in Dercum’s disease? Acta Derm Venereol 1996;76(2):170–1. 16 Oranje AC, Devillers AP. Liposuction in Dercum’s disease: Impact on haemostatic factors associated with cardiovascular disease and insulin sensitivity. J Intern Med 1998;243(3):197–201. 17 Petersen P, Kastrup J. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa). Treatment of the severe pain with intravenous lidocaine. Pain 1987;28(1):77–80. 18 Lennart L. Long standing pain relief of adiposis dolorosa (Dercum’s disease) after intravenous infusion of lidocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15(2):383–5. 19 Atkinson RL. Intravenous lidocaine for the treatment of intractable pain of adiposis dolorosa. Int J Obes 1982;6(4):351–7. 20 Rowbotham MC, Davies PS, Verkempinck C, Galer BS. Lidoderm patch: Double-blind controlled study of a new treatment method for post-herpetic neuralagia. Pain 1996;65(1):39–44. 21 Galer BS, Rowbotham MC, Perander J, Friedman E. Topical lidocaine patch relieves post-herpetic neuralagia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: Results of an enriched enrolled study. Pain 1999;80(3):533–8. 22 Pasero C. Lidocaine patch 5%. Am J Nurs 2003; 103(9):75–8. Downloaded from http://painmedicine.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 24, 2016 has multiple potential side effects and is best administered at a tertiary care facility with significant experience in this modality. Furthermore, repeated treatments with intravenous lidocaine are cumbersome and expensive. Transdermal lidocaine patches have been efficacious in the treatment of neuropathic pain originating from complex regional pain syndrome, painful diabetic neuropathy, and postherpetic neuralagia [20,21]. Systemic effects are very unlikely due to the fact that plasma concentrations of topical lidocaine are well below the concentrations that might cause cardiac anti-arrhythmic activity (1.5 mg/mL) and lidocaine toxicity (5 mg/mL) [22]. Even with administration of a lidocaine patch for 12 hours followed by removal of the patch for 12 hours, the maximal concentration is 0.13 mg/mL, which is well below toxic levels [22]. Desai et al.