* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download NEUMONIA ADQUIRIDA EN LA COMUNIDAD (NAC)

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

NEUMONIA ADQUIRIDA EN

LA COMUNIDAD

(NAC)

Dr. Carlos Fernando Estrada Garzona

Departamento de Farmacología

Universidad de Costa Rica

OBJETIVOS

GENERALIDADES

SEVERIDAD

TRATAMIENTO

EMPIRICO

ESPECIFICO

NEUMONIA COMPLICADA

NAC

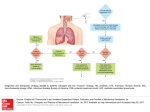

GENERALIDADES caused by Legionella infection. The clinical presentation

of CAP is often more subtle in older patients, and many

of these patients do not exhibit classic symptoms.1 They

often present with weakness and decline in functional

and mental status.

The patient history should focus on detecting symptoms

consistent with CAP, underlying defects in host defenses,

and possible exposure to specific pathogens. Persons with

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or human immunodeficiency virus infection have an increased incidence

tachypnea (LR+ = 3.5). Asymmetric breath sounds,

pleural rubs, egophony, and increased fremitus are relatively uncommon, but are highly specific for pneumonia

(LR+ = 8.0); these signs help rule in pneumonia when

present, but are not helpful when absent.8 Rales or bronchial breath sounds are helpful, but much less accurate

than chest radiography.10 Tachypnea is common in older

patients with CAP, occurring in up to 70 percent of those

older than 65 years.11 Pulse oximetry screening should

be performed in all patients with suspected CAP.12

Table 1. Common Etiologies of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Etiology

Outpatients

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Respiratory viruses

Streptococcal pneumoniae

Chlamydophila pneumoniae

Legionella species

Haemophilus influenzae

Unknown

Frequency

(median

percentage)

Frequency

(median

percentage)

Etiology

16

15

14

12

2

1

44

Inpatients not admitted to ICU

S. pneumoniae

25

Respiratory viruses

10

M. pneumoniae

6

H. influenzae

5

C. pneumoniae

3

Legionella species

3

Unknown

37

Etiology

Frequency

(median

percentage)

Inpatients admitted to ICU

S. pneumoniae

17

Legionella species

10

Gram-negative bacilli

5

Staphylococcus aureus

5

Respiratory viruses

4

H. influenzae

3

Unknown

41

ICU = intensive care unit.

Information from references 1 through 3.

1300 American Family Physician

www.aafp.org/afp

Volume 83, Number 11

Am Fam Physi-‐ cian. 2011;83(11):1299-‐1306 ◆

June 1, 2011

Hotel or cruise ship stay in previous 2 weeks

Legionella species

Travel to or residence in southwestern United States

Travel to or residence in Southeast and East Asia

Coccidioides species, Hantavirus

Burkholderia pseudomallei, avian influenza, SARS

Influenza active in community

Influenza, S. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus,

H. influenzae

Downloaded from http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Costa Rica on August 31, 2014

acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the f

different organizations, and several hav

guidelines for management of CAP. Two

widely referenced are those of the Infect

Table 8. Epidemiologic conditions and/or risk factors related to specific pathogens in community-acquired

Society of America (IDSA) and the Ameri

pneumonia.

Condition

Commonly Society

encountered pathogen(s)

(ATS). In response to confusion r

Alcoholism

Streptococcus pneumoniae, oral anaerobes, Klebsiella

pneumoniae, Acinetobacter species, Mycobacterium

ferences between their respective guidelin

tuberculosis

COPD and/or smoking

Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Legionella species, S.

pneumoniae,

and

theMoraxella

ATScararconvened a joint committee

rhalis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae

Aspiration

Gram-negative enteric pathogens, oral anaerobes

unified

CAP

guideline document.

Lung abscess

CA-MRSA, oral anaerobes,

endemic fungal

pneumonia,

M. tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria

Exposure to bat or bird droppings

Histoplasma capsulatum The guidelines are intended primaril

Exposure to birds

Chlamydophila psittaci (if poultry: avian influenza)

Exposure to rabbits

Francisella tularensis

emergency medicine physicians, hospital

Exposure to farm animals or parturient cats

Coxiella burnetti (Q fever)

HIV infection (early)

S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. tuberculosis

mary

care

practitioners; however, the ext

HIV infection (late)

The pathogens listed for

early infection

plus Pneumocystis jirovecii, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Aspergillus,

atypical mycobacteria (especially Mycobacterium

ture evaluation suggests that they are al

kansasii), P. aeruginosa, H. influenzae

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Lionel A. Mandell, Div. of

McMaster University/Henderson Hospital, 5th Fl., Wing

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cepacia, S. aureus

St.,

Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

Injection drug use

S. aureus, anaerobes, Concession

M. tuberculosis, S.

pneumoniae

Endobronchial obstruction

Anaerobes, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus

This official statement of the Infectious Diseases Society

In context of bioterrorism

Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), Yersinia pestis (plague),

Francisella tularensisand

(tularemia)

the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approved by

NOTE. CA-MRSA, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; COPD,

chronic

pulmonary dis- 2006 and the ATS Board of Directo

Directorsobstructive

on 5 November

ease; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

2006.

a

Committee cochairs.

for pneumonia is uncertain, and few well-controlled studies

Antibiotic Resistance Issues

Cough 12 weeks with whoop or posttussive

vomiting

Structural lung disease (e.g., bronchiectasis)

Resistance to commonly used antibiotics for CAP presents another major consideration in choosing empirical therapy. Resistance patterns clearly vary by geography. Local antibiotic

prescribing patterns are a likely explanation [179–181]. However, clonal spread of resistant strains is well documented.

Bordetella pertussis

have examined the impact of in vitro resistance on clinical

Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 44:S27–72

outcomes of CAP. Published studies are limited by small sample

! 2007

by the design,

Infectious

Society of America.

sizes, biases inherent

in observational

and theDiseases

relative

infrequency of isolates

exhibiting high-level resistance [183–

1058-4838/2007/4405S2-0001$15.00

185]. Current levels of b-lactam resistance do not generally

All r

NAC

SEVERIDAD evel monitoring unit

of the minor criteria

oderate recommen-

vere CAP is 4-fold:

mizes use of limited

ory failure or delayed

2

2

3

3

Septic shock with the need for vasopressors

Downloaded from http://cid.oxfordjournals.

whether to place the

ing unit rather than

10% of hospitalized

n [68–70], but the

s, physicians, hospime of the variability

ability of high-level

ropriate for patients

e respiratory failure

to the ICU, simple

he criteria for a highere CAP. One of the

for ICU care is the

[68–72]. However,

evere CAP were pre-

acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the f

different organizations, and several hav

guidelines for management of CAP. Two

Table 4. Criteria for severe community-acquired pneumonia.

widely referenced are those of the Infect

Society of America (IDSA) and the Ameri

Minor criteriaa

Society (ATS). In response to confusion r

Respiratory rateb !30 breaths/min

PaO /FiO ratiob "250

ferences between their respective guidelin

Multilobar infiltrates

and the ATS convened a joint committee

Confusion/disorientation

Uremia (BUN level, !20 mg/dL)

unified CAP guideline document.

c

Leukopenia (WBC count, !4000 cells/mm )

The guidelines are intended primaril

Thrombocytopenia (platelet count, !100,000 cells/mm )

emergency medicine physicians, hospital

Hypothermia (core temperature, !36!C)

Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation mary care practitioners; however, the ext

Major criteria

ture evaluation suggests that they are al

Invasive mechanical ventilation

NOTE. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; PaO2/FiO2, arterial oxygen pressure/fraction of inspired oxygen; WBC, white blood cell.

Reprints or correspondence:

Dr. Lionel A. Mandell, Div. of

Other criteria to consider include hypoglycemia (in nondiabetic

patients),

McMaster

University/Henderson Hospital, 5th Fl., Wing

acute alcoholism/alcoholic withdrawal, hyponatremia, unexplained metabolic

Concession St., Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

acidosis or elevated lactate level, cirrhosis, and asplenia.

b

Thisrate

official

statement of the Infectious Diseases Society

A need for noninvasive ventilation can substitute for a respiratory

130

and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approved by

breaths/min or a PaO2/FiO2 ratio !250.

c

As a result of infection alone.

Directors on 5 November 2006 and the ATS Board of Directo

2006.

a

Committee cochairs.

a

admission include the initial ATS definition of severe CAP [5]

Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 44:S27–72

and its subsequent modification [6, 82], the CURB !

criteria

[39,

2007 by

the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All r

45], and PSI severity class V (or IV and V) [42].

However,

1058-4838/2007/4405S2-0001$15.00

D E N T I F Y LOW- R I S K PAT I E N TS W I T H C O M M U N I T Y- AC Q U I R E D P N E U M O N I A

ation of each of these

mortality in each of

nd among the three

ality was low for risk

om 0.1 to 0.4 percent

cent for class II, and

ass III. There was no

5) in the area under

ristic curves between

ohort (0.84) and the

rt (0.83). Although

gnificantly greater in

(0.89) than in either

P"0.001), the absoinimal.

ORT patients in the

died (1 in class I, 3 in

nly 4 of these deaths

patients with terminal

obstructive pulmonary

rition. None of these

n preventable.

on between risk class

outcomes evaluated in

Table 4). Among outhospitalization within

t for class I patients to

001). None of the 62

ho were subsequently

was admitted to an inoutpatients in classes

TABLE 2. POINT SCORING SYSTEM FOR STEP 2 OF THE PREDICTION

RULE FOR ASSIGNMENT TO RISK CLASSES II, III, IV, AND V.

CHARACTERISTIC

Demographic factor

Age

Men

Women

Nursing home resident

Coexisting illnesses†

Neoplastic disease

Liver disease

Congestive heart failure

Cerebrovascular disease

Renal disease

Physical-examination findings

Altered mental status‡

Respiratory rate #30/min

Systolic blood pressure "90 mm Hg

Temperature "35°C or #40°C

Pulse #125/min

Laboratory and radiographic findings

Arterial pH "7.35

Blood urea nitrogen #30 mg/dl

(11 mmol/liter)

Sodium "130 mmol/liter

Glucose #250 mg/dl (14 mmol/liter)

Hematocrit "30%

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen

"60 mm Hg§

Pleural effusion

POINTS

ASSIGNED*

Age (yr)

Age (yr)$10

%10

%30

%20

%10

%10

%10

%20

%20

%20

%15

%10

%30

%20

%20

%10

%10

%10

%10

*A total point score for a given patient is obtained by summing the patient’s age in years (age minus 10 for women) and the points for each applicable characteristic. The points assigned to each predictor variable were

based on coefficients obtained from the logistic-regression model used in

step 2 of the prediction rule (see the Methods section).

†Neoplastic disease is defined as any cancer except basal- or squamouscell cancer of the skin that was active at the time of presentation or diagnosed within one year of presentation. Liver disease is defined as a clinical

or histologic diagnosis of cirrhosis or another form of chronic liver disease,

N Engl J Med 1997;336:243-‐50. The New England Journal of Medicine

TABLE 3. COMPARISON

RISK CLASS

(NO. OF

POINTS)†

MEDISGROUPS

DERIVATION COHORT

OF

RISK-CLASS–SPECIFIC MORTALITY RATES

AND VALIDATION COHORTS.*

MEDISGROUPS

VALIDATION COHORT

DERIVATION

PNEUMONIA PORT VALIDATION COHORT

INPATIENTS

I

II ("70)

III (71–90)

IV (91–130)

V (#130)

Total

IN THE

OUTPATIENTS

no. of

patients

%

who died

no. of

patients

%

who died

no. of

patients

%

who died

no. of

patients

%

who died

1,372

2,412

2,632

4,697

3,086

14,199

0.4

0.7

2.8

8.5

31.1

10.2

3,034

5,778

6,790

13,104

9,333

38,039

0.1

0.6

2.8

8.2

29.2

10.6

185

233

254

446

225

1343

0.5

0.9

1.2

9.0

27.1

8.0

587

244

72

40

1

944

0.0

0.4

0.0

12.5

0.0

0.6

ALL PATIENTS

no. of

%

patients who died

772

477

326

486

226

2287

0.1

0.6

0.9

9.3

27.0

5.2

*There were no statistically significant differences in overall mortality or mortality within risk class among patients in

the MedisGroups derivation, MedisGroups validation, or overall Pneumonia PORT validation cohort. The P values for

the comparisons of mortality across risk classes are as follows: class I, P$0.22; class II, P$0.67; class III, P$0.12; class

IV, P$0.69; and class V, P$0.09.

†Inclusion in risk class I was determined by the absence of all predictors identified in step 1 of the prediction rule.

Inclusion in risk classes II, III, IV, and V was determined by a patient’s total risk score, which was computed according

to the scoring system shown in Table 2.

N Engl J Med 1997;336:243-‐50. TABLE 4. MEDICAL OUTCOMES IN THE PNEUMONIA PORT COHORT

ACCORDING TO RISK CLASS.

MEDICAL OUTCOME

Outpatient

CLASS I

CLASS II

CLASS III

CLASS IV

CLASS V

TOTAL

P VALUE

Defining CAP severity on presentation to hospital

Table 3 Multivariate analysis using CURB as a

binary variable (2 or more features = severe) to

identify other factors that are independently associated

with mortality (n=637)

Clinical feature

RESPIRATORY

Albumin <30 g/dl

INFECTION

Age >65 years

Temperature <37°C

CURB score >2 (severe CAP)

Table 5

prediction

and valida

OR

95% CI

p value377

Rule

4.7

3.5

1.9

5.2

2.5 to 8.7

1.6 to 8.0

1.01 to 3.6

2.7 to 10.3

<0.001

0.003

0.047

<0.001

Derivation s

CURB

Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on

resentation to hospital: an international derivation and

alidation study

CURB-65

W S Lim, M M van der Eerden, R Laing, W G Boersma, N Karalus, G I Town, S A Lewis,

T Macfarlane

The univariate association between 30 day mortality and

each potential predictor variable, includingThorax

the2003;58:377–382

CURB score

and each of the components of the CURB score, was analysed

Background: In the assessment

of severity in community acquired pneumonia (CAP), the modified Brit2

test.

To avoid

associations

arising

from

using

a

χ

ish Thoracic Society (mBTS) rule identifies

patientsspurious

with severe pneumonia

but not patients

who might

be suitable for home management. A multicentre study was conducted to derive and validate a practimultiple statistical tests, 12 predictor variables selected from

cal severity assessment model for stratifying adults hospitalised with CAP into different management

groups.the current literature as most consistently important in

Methods: Data from three prospective studies of CAP conducted in the UK, New Zealand,

and the

3–5 7 11–19

predicting

prognosis

in comprising

CAP were

examined.

Netherlands

were combined.

A derivation cohort

80% of the

data was used to develop theThis

..........................................................................................................................

e end of article for

hors’ affiliations

....................

CRB-65

All patients were treated with empirical antimicrobial

agents according to local hospital guidelines. This usually

comprised a β-lactamase stable β-lactam in combination with

a macrolide. Dutch patients were randomised within 2 hours

CURB score of 2 or more—in the derivation cohort was 75%

(95% CI 72 to 78) and 69% (95% CI 66 to 72), respectively.

Corresponding values in the validation cohort were 74% (95%

CI 68 to 80) and 73% (95% CI 67 to 79).

≥

≤

≥

377

RESPIRATORY INFECTION

Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on

presentation to hospital: an international derivation and

validation study

assessment in a hospital setting: the CURB-65 score. One step strategy for stratifying patients with CAP into risk groups

W S Lim,Figure

M 2MtoSeverity

van

der Eerden,

R the

Laing,

WG

N Karalus, G I Town, S A Lewis,

according

risk of mortality

at 30 days when

results of blood

ureaBoersma,

are available.

J T Macfarlane

.............................................................................................................................

www.thoraxjnl.com

Thorax 2003;58:377–382

Background: In the assessment of severity in community acquired pneumonia (CAP), the modified British Thoracic Society (mBTS) rule identifies patients with severe pneumonia but not patients who might

be suitable for home management. A multicentre study was conducted to derive and validate a practical severity assessment model for stratifying adults hospitalised with CAP into different management

Defining CAP severity on presentation to hospital

381

≥

≤

≥

377

RESPIRATORY INFECTION

Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on

presentation to hospital: an international derivation and

validation study

Figure 3 Clinical severity assessment in the community setting: the CRB-65 score. Strategy for stratifying patients with CAP into risk groups in

the community using only clinical observations (when blood urea results not available).

W S Lim, M M van der Eerden, R Laing, W G Boersma, N Karalus, G I Town, S A Lewis,

J T Macfarlane

Based on the results of the multivariate analysis, age >65

Although the profiles of the three cohorts are very similar

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .years

. . . . .was

. . . .added

. . . . . .as

. . another

. . . . . . . .adverse

. . . . . . .prognostic

. . . . . . . . . feature

. . . . . . .to

. .the

. . . . . . .(table

. . . . . 1),

. . .there

. . . . .may

. . . .be

. . other

. . . . . potential

. . . . . . . . differences

. . . . . . . . . . between

. . . . . . . .the

.

cohorts which may not be obvious. This represents a limitation

CURB score resulting in a six point score (CURB-65, range

Thorax 2003;58:377–382

of the study.

0–5) which allowed patients to be stratified according to

The importance of mental confusion, low blood pressure,

increasing risk of mortality ranging from 0.7% (score 0) to

raised respiratory rate, and raised urea as “core” adverse prog40% (score 4; table 4) The numbers with a score of 5 (highest)

Background: In the assessment of severity in community

acquired pneumonia (CAP), the modified Britnostic features in patients admitted to hospital with CAP is

were small; of the seven patients, only one (14%) died.

ish

Thoracic

Society

(mBTS)

rule

identifies

patients

with

severe

but not

who might

underlined. Thispneumonia

study confirmed

our patients

previous finding

in the

However, three (43%) others required mechanical ventilation

be

suitable

for

home

management.

A

multicentre

study

was

conducted

to

derive

and

validate

a practiUK subset of patients that a simple severity scoring

system

in an intensive care setting and survived. A further model

severityfeatures

assessment

model

stratifying

hospitalised

with

CAPprognostic

into different

management

based

on these four

adverse

features

(CURB score)

based onlycal

on clinical

available

from afor

clinical

assess- adults

See end of article forment without

correlates well with mortality.6

groups.

laboratory results (confusion, respiratory rate,

authors’ affiliations

NAC

COMPLICADA are major causes of apparent antibiotic failure. Therefore, the

first response to nonresponse or deterioration is to reevaluate

the initial microbiological results. Culture or sensitivity data

not available at admission may now make the cause of clinical

failure obvious. In addition, a further history of any risk factors

for infection with unusual microorganisms (table 8) should be

taken if not done previously. Viruses are relatively neglected as

a

Fluoroquinolone therapy

Concordant therapy

Discordant therapy

b

0.5

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

0.61

…

…

2.51

urnals.org/ at Universidad de Costa Rica on August 31, 2014

acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the f

different organizations, and several hav

guidelines for management of CAP. Two

widely referenced are those of the Infect

Society of America (IDSA) and the Ameri

Table 12. Factors associated with nonresponding pneumonia.

Society (ATS). In response to confusion r

Overall failure

Early failure

ferences

between their respective guidelin

Risk factor

Decreased risk Increased risk Decreased risk Increased risk

Older age (165 years)

…

…

0.35and the …

ATS convened a joint committee

COPD

0.60

…

…

…

Liver disease

…

2.0

… unified CAP

…

guideline document.

Vaccination

0.3

…

…

…

Pleural effusion

…

2.7

…

…

The guidelines

are intended primaril

Multilobar infiltrates

…

2.1

…

1.81

medicine physicians, hospital

Cavitation

…

4.1

… emergency

…

Leukopenia

…

3.7

…

…

mary

care

PSI class

…

1.3

…

2.75 practitioners; however, the ext

Legionella pneumonia

…

…

…

2.71

ture

evaluation

suggests that they are al

Gram-negative pneumonia

…

…

…

4.34

CAP. Although in the original study only 8 (16%) of 49 cases

could not be classified [101], a subsequent prospective multicenter trial found that the cause of failure could not be determined in 44% [84].

Management of nonresponding CAP. Nonresponse to antibiotics in CAP will generally result in !1 of 3 clinical responses: (1) transfer of the patient to a higher level of care, (2)

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Lionel A. Mandell, Div. of

McMaster University/Henderson Hospital, 5th Fl., Wing

Concession St., Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

This official statement of the Infectious Diseases Society

and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approved by

Directors on 5 November 2006 and the ATS Board of Directo

2006.

a

Committee cochairs.

NOTE. Data are relative risk values. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PSI, Pneumonia Severity

Index.

a

b

From [84].

From [81].

S58 • CID 2007:44 (Suppl 2) • Mandell et al.

Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 44:S27–72

! 2007 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All r

1058-4838/2007/4405S2-0001$15.00

practice

M.P.H.,

eM.D.,

w e ng

l a n d jEditor

o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

uired Pneumonia

ciated Pneumonia.

Table 3. Clinical Features Suggesting CommunityAcquired MRSA Pneumonia.*

CavitaryM.B.,

infiltrate or

necrosisPh.D.

Grant

W.

B.S.,

e previous 90

daysWaterer,

ded-care facility

Rapidly increasing pleural effusion

Gross hemoptysis (not just blood-streaked)

home,

including

ette highlighting

aConcurrent

commoninfluenza

clinical problem.

sented, followed byNeutropenia

a review of formal guidelines,

the authors’ clinicalErythematous

recommendations.

rash

days

ant pathogen

Skin pustules

py† disease who

Young,

healthy

patient of proFrom the Division of Pulmonary and Criter’s

haspreviously

a 2-day

history

Severe pneumonia during summer months

sion is transferred

from a nursing home to ical Care Medicine, Northwestern Unie previous 90 days

versity Feinberg School of Medicine, Chi*

MRSA

denotes

methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus

the

she has had no recent cago (R.G.W., G.W.W.); and the University

days transfer records,

aureus.

c agents. Her temperature is 38.4°C (101°F), of Western Australia, Perth (G.W.W.). Address reprint requests to Dr. Wunderink

espiratory ratepulmonary

is 30 breaths

minute,

thereceived

disease per

[COPD])

who have

at [email protected].

multiple

courses

of

outpatient

antibiotics;

the

he

oxygen

saturation

is

91%

while

she

is

s

frequency of P. aeruginosa infection is particularly

N Engl J Med 2014;370:543-51.

in both lower increased

lung fields.

She

is

oriented

to

13

in this population.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcp1214869

n Thoracic Society

28

Whereas

is sodium

commonly level

identifiedCopyright

in

er cubic

millimeter,

theMRSA

serum

merica.

© 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society

original criteria but patients with risk factors for health care–associitrogen

is 25 mg per deciliter (9.0 mmol per

s of health care–

ated pneumonia, a community-acquired strain of

NAC

TRATAMIENTO acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the f

different organizations, and several hav

guidelines

for management

ofcatarrhalis,

CAP. Two

andgenerally

Moraxella

gen

Table 7.empirical

Recommended

antibiotics and

for communityMoraxella catarrhalis,

in patients

who have

Table 7. Recommended

antibioticsempirical

for communityacquired pneumonia.

acquired pneumonia.

widely bronchopulmonary

referencedderlying

aredisease,

those

ofS.the

Infect

bronchopulmonary

derlying

and

aureus,

esped

during

an of

influenza

outbreak.

Risks

for

infection

with E

during

an influenza

Society

America

(IDSA)

and

theoutbreak

Ameri

Outpatient treatment

Outpatient treatment

obacteriaceae species and

P. aeruginosaspecies

as etiologies

fora

obacteriaceae

and P.

1. Previously healthy

and no use healthy

of antimicrobials

within

1. Previously

and no use

of the

antimicrobials

within

the

Society

(ATS).

In

response

to

confusion

r

are chronic oral steroidare

administration

or steroid

severe under

previous 3 months

chronic

oral

adm

previous 3 months

bronchopulmonary

disease,

alcoholism,

and frequent

antib

A macrolide (strong recommendation; level I evidence)

ferences between

their

respective

guidelin

bronchopulmonary

disease,

al

A macrolide (strong recommendation; level I evidence)

therapy [79, 131], whereas recent hospitalization would d

Doxycyline (weak recommendation; level III evidence)

therapy a[79,

131],committee

whereas rec

Doxycyline (weak recommendation; level III evidence)

and asthe

ATSLess

convened

joint

cases

HCAP.

common causes

of pneumonia inc

2. Presence of comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver

casesto,as

HCAP. Less

common

2. Presence

of comorbidities

as chronic heart,

liver

or renal disease;

diabetes mellitus;

alcoholism;such

malignanbut

arelung,

by no

means

limited

Streptococcus

pyogenes,

Nei

unified

CAP

guideline

document.

or renal disease;conditions

diabetesormellitus;

cies; asplenia; immunosuppressing

use of alcoholism; malignanbut

are

by

no

means

limited

to

meningitidis, Pasteurella multocida, and H. influenzae typ

immunosuppressing

drugs;

or use immunosuppressing

of antimicrobials withinconditionsThe

cies;

asplenia;

or useguidelines

of

are intended

primaril

meningitidis,

Pasteurella

multo

The “atypical”

the previous 3 months

(in which case an drugs;

alternative

fromofa antimicrobials

immunosuppressing

or use

within organisms, so called because they are

different class should

selected)

Thecultivatable

“atypical”onorganisms,

emergency

medicine

physicians,

hospital

detectable

on

Gram

standard

ba

the be

previous

3 months (in which case an alternative

from

a stain or

A respiratory fluoroquinolone

different(moxifloxacin,

class shouldgemifloxacin,

be selected)or

ologic media, include M.detectable

pneumoniae,

pneumoniae,

Le

on C.Gram

stain

or

mary

care

practitioners;

however,

the

ext

levofloxacin [750 mg]) (strong recommendation; level I

A respiratory fluoroquinolone (moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin,

or respiratory

ella species, and

viruses.

With

the exception

o

ologic

media,

include

M. pneu

evidence)

levofloxacin [750 mg]) (strong recommendation;

level

I

ture evaluation

suggests

thatarethey

arecaus

alvi

gionella

species, these microorganisms

common

A b-lactam plus a macrolide (strong recommendation; level I

ella species, and

respiratory

evidence)

evidence)

pneumonia, especially among outpatients. However, these

gionella species, these microo

A

b-lactam

plus

a

macrolide

(strong

recommendation;

level I

3. In regions with a high rate (125%) of infection with high-level

ogens are not often identified in clinical practice because,

evidence)

pneumonia, especially among

(MIC !16 mg/mL) macrolide-resistant

Streptococcus pneua

few

exceptions,

such

as

L. pneumophila and influenza v

moniae, consider

of alternative

listed

above of

in infectionReprints

3. Inuse

regions

with a agents

high rate

(125%)

with high-level

or correspondence:

Dr.are

Lionel

Mandell,

Div. of

ogens

notA.

often

identified

no

specific,

rapid,

or

standardized

tests

for

their

detection

(2) for patients without

comorbidities

(moderate

recommen(MIC !16 mg/mL) macrolide-resistant Streptococcus

McMaster pneuUniversity/Henderson

Hospital, 5thsuch

Fl., as

Wing

a fewthe

exceptions,

L.

dation; level III evidence)

influenza

remains

predominant viral

caup

moniae, consider use of alternative agentsAlthough

listed above

in

Concession St., Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

Inpatients, non-ICU treatment

no specific,

rapid,viruses

or standardi

(2) for patients without comorbidities (moderate

CAP

inrecommenadults, statement

other commonly

recognized

include

This

official

of

the

Infectious

Diseases

Society

A respiratory fluoroquinolone

recommendation;

level I

dation;(strong

level III

evidence)

Although

influenza

remains

[107],

adenovirus,

and

parainfluenza

virus,

as

well

as

and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approvedless

by

evidence)

Inpatients, non-ICU treatment

mon

viruses,

including

human

metapneumovirus,

herpes

CAP

in

adults,

other

commonl

Directors on 5 November 2006 and the ATS Board of Directo

A b-lactam plus a macrolide (strong recommendation; level I

A

respiratory

fluoroquinolone

(strong

recommendation;

level I

plex

virus,adenovirus,

SARS-associated

coronav

evidence)

[107],

and parainfl

2006.virus, varicella-zoster

evidence)

anda measles

virus.

In a recent

of immunocompetent

Inpatients, ICU treatment

Committee

cochairs.

mon study

viruses,

including human

A

b-lactam

plus

a

macrolide

(strong

recommendation;

level

I

A b-lactam (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, or ampicillin-sulbactam)

patients admitted to the hospital with CAP, 18% had evid

plex virus,

viru

Clinical Infectious Diseases

2007;varicella-zoster

44:S27–72

evidence)

plus either azithromycin

(level II evidence) or a respiratory

of a viral etiology, and, in 9%, a respiratory virus was the

! 2007 by the Infectiousand

Diseases

Society

of America.

All rs

fluoroquinolone

(level I ICU

evidence)

(strong recommendation)

measles

virus.

In a recent

Inpatients,

treatment

pathogen

identified

[176].

Studies

that

include

outpatient

(for penicillin-allergic patients, a respiratory fluoroquinolone

1058-4838/2007/4405S2-0001$15.00

A b-lactam (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, or ampicillin-sulbactam)

patients admitted to the hosp

levofloxacin [750 mg]) (strong recommendation; level I

evidence)

acquired ella

pneumonia

(CAP) viruses.

has been

species, and respiratory

With the

the exf

gionella species, these microorganisms are comm

A b-lactam plus a macrolide (strong recommendation;different

level I

organizations, and several hav

evidence)

pneumonia, especially among outpatients. Howev

3. In regions with a high rate (125%) of infection with high-level

guidelinesogens

foraremanagement

CAP.practice

Two

not often identifiedof

in clinical

and

Moraxella catarrhalis, generally in patients who have

Table 7. Recommended(MIC

empirical

antibiotics

for community!16 mg/mL)

macrolide-resistant

Streptococcus

pneua few exceptions, such as L. pneumophila and in

in

acquired pneumonia. moniae, consider use of alternative agents listed above

widely

referenced

aredisease,

thoseand

ofS.the

Infect

derlying

bronchopulmonary

aureus,

espe

no specific, rapid, or standardized tests for their d

(2) for patients without comorbidities (moderate recommenduring

an of

influenza

outbreak.

Risks

for

infection

with E

dation; level III evidence)

Although

influenza

remains

the

predominant

Society

America

(IDSA)

and

the

Ameri

Outpatient treatment

Inpatients, non-ICU treatment

obacteriaceaeCAP

species

and other

P. aeruginosa

etiologiesviruse

for

in adults,

commonlyasrecognized

1. Previously healthy and no use of antimicrobials within the

Society

(ATS).

In

response

to

confusion

A respiratory fluoroquinolone (strong recommendation; are

level chronic

I

oral steroid

administration

or severe

[107],

adenovirus,

and parainfluenza

virus,under

as wer

previous 3 monthsevidence)

bronchopulmonary

disease,

alcoholism,

frequent

antib

mon viruses,

including

humanand

metapneumoviru

A macrolide (strong

recommendation;

level(strong

I evidence)

ferences

between

their

respective

guidelin

A b-lactam

plus a macrolide

recommendation; level

I

varicella-zoster

virus, SARS-associated

therapy [79, plex

131],virus,

whereas

recent hospitalization

would d

evidence)

Doxycyline (weak recommendation;

level III evidence)

and

the

ATS

convened

a

joint

committee

and measles

virus. In causes

a recent of

study

of immunoco

Inpatients, ICUsuch

treatment

cases as HCAP.

Less common

pneumonia

inc

2. Presence of comorbidities

as chronic heart, lung, liver

A

b-lactam

(cefotaxime,

ceftriaxone,

or

ampicillin-sulbactam)

or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignanpatients

admitted

to Streptococcus

the

hospital with

CAP, 18%

but

are by no

means

limited to,

pyogenes,

Nei

unified

CAP

guideline

document.

plus either azithromycin

(level or

II evidence)

cies; asplenia; immunosuppressing

conditions

use of or a respiratory

of

a

viral

etiology,

and,

in

9%,

a

respiratory

viru

meningitidis, Pasteurella multocida, and H. influenzae typ

fluoroquinolone

I evidence) (strong

recommendation)

immunosuppressing

drugs; or use(level

of antimicrobials

within

The guidelines

are so

intended

primaril

pathogen

identified

[176].

Studies

that

include

ou

(for penicillin-allergic

a respiratory

The “atypical”

organisms,

called

because

they are

the previous 3 months

(in which casepatients,

an alternative

from afluoroquinolone

and be

aztreonam

are recommended)

viral pneumonia rates as high as 36% [167]. The

different class should

selected)

emergency

medicine

physicians,

hospital

detectable

on Gram

stain or cultivatable

on standard

ba

Special concerns

other

etiologic

agents—for

example,

M.

tubercu

A respiratory fluoroquinolone (moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin, or

ologic media, include M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, Le

Pseudomonas

is arecommendation;

consideration

mary caredophila

practitioners;

however,

the ext

psittaci (psittacosis),

Coxiella burnetii

(Q

levofloxacin If[750

mg]) (strong

level I

ella

species,

and

respiratory

viruses.

With

the

exception

o

An

antipneumococcal,

antipseudomonal

b-lactam

(piperacillinevidence)

cisella tularensis (tularemia), Bordetella pertuss

tazobactam, cefepime, imipenem, or meropenem)

plus

ture evaluation

suggests

that(Histoplasma

they

arecapsu

al

gionella

species,

theseand

microorganisms

common

caus

A b-lactam plus a macrolide (strong recommendation; level I

cough),

endemic fungi are

either ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin (750 mg)

evidence)

pneumonia, dioides

especially

among

outpatients.

However,and

these

immitis,

Cryptococcus

neoformans,

Bla

or

3. In regions with a The

highabove

rate (1b-lactam

25%) ofplus

infection

with

high-level

ogens are notinis)—is

often identified

in clinical

because,

largely determined

bypractice

the epidemiologic

an aminoglycoside and azithromycin

(MIC !16 mg/mL) macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneuor

a few exceptions,

L. pneumophila

and[113,

influenza

v

8) butsuch

rarelyasexceeds

2%–3% total

177]. T

moniae, consider use of alternative agents listed above in

Reprints

or

correspondence:

Dr.

Lionel

A.

Mandell,

Div.

of

The above b-lactam plus an aminoglycoside and an antipneumay be

fungitests

in the

geog

no specific, rapid,

or endemic

standardized

forappropriate

their detection

(2) for patients without

comorbidities (moderate recommenMcMaster University/Henderson Hospital, 5th Fl., Wing

mococcal fluoroquinolone (for penicillin-allergic patients,

dation; level III evidence)

bution [100].

Although influenza

remains the predominant viral cau

substitute aztreonam for above b-lactam)

Concession St., Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

Inpatients, non-ICU treatment

The

need

for specific

anaerobicviruses

coverage

for CA

CAP

in official

adults, statement

other

commonly

recognized

include

(moderate recommendation; level III evidence)

This

of

the

Infectious

Diseases

Society

A respiratory fluoroquinolone

recommendation;

level I or linezolid

overestimated.

Anaerobic bacteria

cannot

de

If CA-MRSA(strong

is a consideration,

add vancomycin

[107],

adenovirus,

and parainfluenza

virus,

asapproved

well asbe

less

and

the

American

Thoracic

Society

(ATS)

was

by

evidence)

(moderate recommendation; level III evidence)

agnostic techniques in current use. Anaerobic cov

mon

viruses,

including

human

metapneumovirus,

herpes

Directors

on

5

November

2006

and

the ATS

Board ofpleuropu

Directo

A b-lactam plus a macrolide (strong recommendation; level I

indicated

only

in

the

classic

aspiration

NOTE. CA-MRSA, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococplex

evidence) cus aureus; ICU, intensive care unit.

2006.virus, varicella-zoster virus, SARS-associated coronav

drome in patients with a history of loss of cons

anda measles

virus.

In a recent study of immunocompetent

Inpatients, ICU treatment

Committee

cochairs.

result

of alcohol/drug overdose or after seizures in

A b-lactam (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, or ampicillin-sulbactam)

patients admitted

to the gingival

hospitaldisease

with CAP,

18% had mot

evid

concomitant

or esophogeal

SARS-associated

continually increases

the Infectious

Clinical

Diseases 2007;

44:S27–72

plus either azithromycin

(levelcoronavirus

II evidence)[170],

or a respiratory

of a viral etiology,

and,trials

in 9%,

virus was

the

Antibiotic

havea respiratory

not

demonstrated

a need

challenge

appropriate

management.

! 2007 by the

Infectious

Diseases

Society

of America.

All r

fluoroquinolone

(level for

I evidence)

(strong

recommendation)

pathogen

identified

[176].

Studies in

that

outpatient

treat these

organisms

theinclude

majority

of CAP

(for penicillin-allergic

respiratory

fluoroquinolone

Table 6patients,

lists the amost

common

causes of CAP, in decreasing

1058-4838/2007/4405S2-0001$15.00

Table 9. Recommended antimicrobial therapy for specific pathogens.

Organism

Preferred antimicrobial(s)

acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the f

different organizations, and several hav

guidelines for management of CAP. Two

widely referenced are those of the Infect

Society of America (IDSA) and the Ameri

Society (ATS). In response to confusion r

ferences between their respective guidelin

and the ATS convened a joint committee

unified CAP guideline document.

The guidelines are intended primaril

emergency medicine physicians, hospital

mary care practitioners; however, the ext

ture evaluation suggests that they are al

Alternative antimicrobial(s)

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Penicillin G, amoxicillin

Macrolide, cephalosporins (oral [cefpodoxime, cefprozil, cefuroxime, cefdinir, cefditoren] or parenteral [cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime]), clindamycin,

doxycyline, respiratory fluoroquinolonea

Penicillin resistant; MIC !2 mg/mL

Agents chosen on the basis of susceptibility, including cefotaxime, ceftriaxone,

fluoroquinolone

Vancomycin, linezolid, high-dose amoxicillin

(3 g/day with penicillin MIC "4 mg/mL)

Amoxicillin

Fluoroquinolone, doxycycline, azithromycin,

clarithromycinb

Second- or third-generation cephalosporin,

amoxicillin-clavulanate

Fluoroquinolone, doxycycline, azithromycin,

b

clarithromycin

Mycoplasma pneumoniae/Chlamydophila

pneumoniae

Legionella species

Chlamydophila psittaci

Coxiella burnetii

Macrolide, a tetracycline

Fluoroquinolone

Fluoroquinolone, azithromycin

A tetracycline

A tetracycline

Doxycyline

Macrolide

Macrolide

Francisella tularensis

Yersinisa pestis

Doxycycline

Streptomycin, gentamicin

Gentamicin, streptomycin

Doxycyline, fluoroquinolone

Bacillus anthracis (inhalation)

Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, doxycycline

(usually with second agent)

Other fluoroquinolones; b-lactam, if

susceptible; rifampin; clindamycin;

chloramphenicol

Enterobacteriaceae

Third-generation cephalosporin, carbapenemc (drug of choice if extended-spectrum b-lactamase producer)

b-Lactam/b-lactamase inhibitor,

fluoroquinolone

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Burkholderia pseudomallei

Antipseudomonal b-lactam plus (ciproflox- Aminoglycoside plus (ciprofloxacin or

f

f

acin or levofloxacin or aminoglycoside)

levofloxacin )

Carbapenem, ceftazadime

Fluoroquinolone, TMP-SMX

Acinetobacter species

Carbapenem

Haemophilus influenzae

Non–b-lactamase producing

b-Lactamase producing

e

d

Cephalosporin-aminoglycoside, ampicillinsulbactam, colistin

Staphylococcus aureus

Downloaded from http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Costa Rica on August 31, 2014

Penicillin nonresistant; MIC !2 mg/mL

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Lionel A. Mandell, Div. of

Bordetella pertussis

Macrolide

TMP-SMX

McMaster University/Henderson Hospital, 5th Fl., Wing

Carbapenem

Anaerobe (aspiration)

b-Lactam/b-lactamase inhibitor,

clindamycin

Concession St., Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

Influenza virus

Oseltamivir or zanamivir

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Isoniazid plus rifampin plus ethambutol

Refer to [243] for specific This official statement of the Infectious Diseases Society

plus pyrazinamide

recommendations

Coccidioides species

For uncomplicated infection in a normal

Amphotericin B

and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approved by

host, no therapy generally recommended; for therapy, itraconazole,

Directors on 5 November 2006 and the ATS Board of Directo

fluconazole

Histoplasmosis

Itraconazole

Amphotericin B

2006.

Blastomycosis

Itraconazole

Amphotericin B

a

cochairs.

NOTE. Choices should be modified on the basis of susceptibility test results and advice from local specialists. Refer to local referencesCommittee

for appropriate

Methicillin susceptible

Antistaphylococcal penicilling

Methicillin resistant

Vancomycin or linezolid

Cefazolin, clindamycin

TMP-SMX

d

doses. ATS, American Thoracic Society; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; TMP-SMX,

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

a

Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 44:S27–72

! 2007 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All r

1058-4838/2007/4405S2-0001$15.00

Levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin (not a first-line choice for penicillin susceptible strains); ciprofloxacin is appropriate for Legionella and most

gram-negative bacilli (including H. influenza).

b

Azithromycin is more active in vitro than clarithromycin for H. influenza.

c

Imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem, ertapenem.

d

Piperacillin-tazobactam for gram-negative bacilli, ticarcillin-clavulanate, ampicillin-sulbactam or amoxicillin-clavulanate.

e

Ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, imipenem, meropenem.

f

750 mg daily.

Systematic review

%

Study

ID

OR (95% CI)

Weight

0.73 (0.60, 0.89)

20.07

Dudas 2000

0.42 (0.14, 1.26)

0.71

Houck 2001

0.65 (0.49, 0.86)

10.34

Waterer 2001

0.33 (0.13, 0.84)

0.98

Martinez 2003

Garcia Vazquez 2005

0.40 (0.17, 0.94)

0.50 (0.31, 0.81)

1.17

3.66

Aspa 2006

0.98 (0.55, 1.75)

2.53

Dwyer 2006

1.09 (0.41, 2.90)

0.89

Metersky 2007

Paul 2007

0.61 (0.43, 0.87)

0.69 (0.32, 1.49)

6.70

1.44

Rodriguez 2007

0.58 (0.36, 0.93)

3.75

Blasi 2008

Bratzler 2008

0.40 (0.23, 0.70)

0.70 (0.57, 0.86)

2.74

18.58

Tessmer 2009

0.53 (0.30, 0.94)

2.60

Naucler 2013

0.24 (0.03, 1.92)

0.20

Rodrigo 2013

Overall (I2 = 2.7%, P = 0.422)

0.72 (0.60, 0.86)

23.64

0.67 (0.61, 0.73)

100.00

NOTE: Weights are from random effects analysis

.03

.1

.3

1

3.3

10

30

Figure 2. Comparison of the effects of BLM dual therapy and BL monotherapy on reduction in mortality. The vertical line shows the point of no difference

between the two therapies, squares show ORs, the diamond shows the pooled OR for all studies and horizontal lines show the 95% CIs.

Table 2. Subgroup analyses of mortality risk

Test of association

Characteristics

All studies

Site

ward

Downloaded from http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Costa Rica on Augus

Gleason 1999

J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 1441 – 1446

doi:10.1093/jac/dku033 AdvanceHeterogeneity

Access publication 16 February 2014

No. of studies

OR (95% CI)a

Z

P

16

0.66 (0.61–0.73)

8.60

,0.001

8

0.64 (0.55–0.73)

6.28

Model

x2

P

I 2 (%)

R

15.47

0.42

3.0

b-Lactam/macrolide

dual

therapy

versus b-la

treatment

of 11.46

community-acquired

pneumon

,0.001

R

0.12

39.0

of adverse

3%) of 256

72 patients

he 750-mg

up were evluable popnts (33.8%)

le 3).

oth the ITT

oportion of

I class III/

nt arm and

sided Fish-

nt, the clination were

and 91.1%

CI, "7.0 to

rates were

ponse rates

ble 6.

erapy visits

of 166 patients in the 500-mg group were initially thought to

have experienced clinical relapses

(P p .10

, bythe

2-sided

Fisher’s of drug-resistan

etiologies

and

emergence

exact test). Upon detailed examination, 5 patients were con-

Streptococcus pneumoniae has long been iden

most important pathogen among adults wi

Table 5. Clinical success rates for the clinically evaluable population at the 7–14-day posttherapy

according to the Pneulowed visit,

by Haemophilus

influenzae, Moraxella

monia Severity Index (PSI) score.

and Staphylococcus aureus [1–4]. However, re

a

n/N

(%)

have documented an increased incidence of

750-mg groupb 500-mg groupc

due to (n“atypical”

(e.g.,

Patient category

(n p 198)

p 192)

95% CIdLegionella pneumop

Evaluable patients 183/198 (92.4) 175/192 (91.1) "7.0 to 4.4

Stratum Ie

Total

69/76 (90.8)

PSI class IIIf

44/49 (89.8)

44/51

to 10.2

Received

25 (86.3)

February "17.2

2003; accepted

g

PSI class IV

h

PSI class V

i

Stratum II

a

73/86 (84.9)

25/27 (92.6)

27/32 (84.4)

August 2003.

0/0 (0.0)

2/3 (66.7)

"16.5 to 4.7

2 May 2003; electronic

"26.1 to 9.6

Not applicable

Financial support: Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical.

114/122 (93.4) 102/106 (96.2) "3.4 to 9.0

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Alan Tennenberg, Ortho-McNe

No. of patients in the category with clinically successful treatment/no. of

1000 Rt. 202 S, Raritan, NJ 08869-0602 ([email protected].

patients in the category (%).

b

Levofloxacin, 750 mg q.d. iv Clinical

or po for 5Infectious

days.

Diseases 2003; 37:752–60

c

Levofloxacin, 500 mg q.d. iv or po for 10 days.

d

! 2003

by the

Infectious

Diseases

Society of America. All righ

Two-sided 95% CI around the

difference

(10-day

levofloxacin

regimen

minus 5-day levofloxacin regimen).

1058-4838/2003/3706-0002$15.00

e

PSI classes III, IV, and V combined.

f

P

ct of the intervention

eat population. Solid

g rank, 0.60; hazard

P 5 0.44.

anically ventilated

ary and secondary

de in 118 (55.4%)

he most frequently

n of the pathogens

e 5. Patients with

nia Severity Index.

Measurements and Main Results: We enrolled 213 patients. Fifty-four

(25.4%) patients had a CURB-65 score greater than 2, and 93

(43.7%) patients were in Pneumonia Severity Index class IV-V.

Clinical cure at Days 7 and 30 was 84/104 (80.8%) and 69/104

(66.3%) in the prednisolone group and 93/109 (85.3%) and 84/109

979 group (P 5 0.38 and P 5 0.08). Patients on

(77.1%) in the placebo

prednisolone had faster defervescence and faster decline in serum

C-reactive protein levels compared with placebo. Subanalysis of

patients with severe pneumonia did not show differences in clinical

outcome. Late failure (.72 h after admittance) was more common in

the prednisolone group (20 patients, 19.2%) than in the placebo

group (10 patients, 6.4%; P 5 0.04). Adverse events were few and not

different between the two groups.

Conclusions: Prednisolone (at 40 mg) once daily for a week does not

improve outcome in hospitalized patients with CAP. A benefit in

more severely ill patients cannot be excluded. Because of its

association with increased late failure and lack of efficacy prednisolone should not be recommended as routine adjunctive treatment

in CAP.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 00170196).

Keywords: community-acquired pneumonia; corticosteroids; infection

(Received in original form May 29, 2009; accepted in final form February 1, 2010)

Supported by an unrestricted grant from Astra Zeneca.

Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of

an abstract at the 2009 annual ATS conference (Snijders D, de Graaff CS, van der

Werf TS, Boersma WG. Clinical efficacy of prednisolone in patients with

4. Defervescence in patients with community-acquired

pneucommunity-acquired

pneumonia, a randomized clinical trial [abstract A6116].

Presented

at the 2009 ATS International Conference, May 15–20.).

treated with prednisolone or placebo. Diamonds

5 pednisolone;

Figure

monia

and requests

squares 5 placebo. Data are presented as mean 6 Correspondence

SD. * P , 0.01.

for reprints should be addressed to Dominic

Snijders, M.D., Department of Pulmonary Diseases, Medical Centre Alkmaar,

Wilhelminalaan 15, 1812 JD Alkmaar, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of

patients hospitalized with CAP; clinical cure was

equal

in both

contents

at www.atsjournals.org

groups at Day 7. A trend toward a higher clinical

cure

rate

Am J Respir

Crit Care

MedinVol 181. pp 975–982, 2010

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0808OC on February 4, 2010

the placebo group was observed. The overall Internet

clinical

cure rate

address: www.atsjournals.org

(83% at Day 7 and 71.8% at Day 30) is in concordance with

other studies (15). Our findings contrast with the findings in

other recent studies. In experimental studies a benefit has been

found with the combination of hydrocortisone and antibiotics

Citation:

thors have declared that no competing interests

exist.Nie W, Zhang Y, Cheng J, Xiu Q (2012) Corticosteroids in the Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

e47926. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047926

Editor: Miguel Santin, Barcelona University Hospital, Spain

qually to this work.

Received May 31, 2012; Accepted September 18, 2012; Published October 24, 2012

Copyright: ! 2012 Nie et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attr

use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This study was supported by grant no. 81170025 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China an

and Development" from the National Ministry of Science and Technology (no. 2011ZX09302-003-001). The funders h

Corticosteroids for CAP

and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

with antibiotics attenuated local inflammatory response and

Competing

Interests: The

authors haveburden

declared that

competing

interests exist. model of severe

decreased

bacterial

innothe

experimental

eumonia (CAP) is a common and* E-mail: pneumonia

[email protected]

[5]. In a mouse pneumonia model, Li et al. [6] found

authors contributed equally to this work.

associated with high morbidity and. These that

hydrocortisone decreased inflammatory response significantly.

eading cause of death and the most

In addition, Salluh et al. [7] reported that relative adrenal

death worldwide [1]. Despite effective

Introduction

insufficiency occurred in most of the patientswith

withantibiotics

severe attenuate

CAP,

decreased

bacterial

burden

12–36% patients admitted to theCommunity-acquired

suggesting underlying

benefits

corticosteroids

treatment

in

these

pneumonia (CAP)

is aofcommon

and

pneumonia [5]. In a mouse

th severe CAP die within a short time

serious infectious

disease

associated

with

high

morbidity

and

that hydrocortisone

decreas

patients. Taken together, these facts indicated

a potential

mortality.

It

is

the

sixth

leading

cause

of

death

and

the

most

In addition, Salluh et al

ment of an efficacious treatment has

beneficial

effect

of worldwide

corticosteroids

in effective

pneumonia.

common infectious

cause

of death

[1]. Despite

insufficiency occurred in m

educing the high mortality.

antibiotic therapy,

about a12–36%

patients randomized

admitted to thecontrolled

Recently,

multicenter

(RCT)

suggestingtrial

underlying

bene

intensive

care

unit

(ICU)

with

severe

CAP

die

within

a

short

time

onia, inflammatory cytokines, such as

patients.

together

performed by Confalonieri et al. [8] demonstrated

thatTaken

hydrocor[2]. Therefore, the development of an efficacious treatment has

beneficial effect of corticos

IL-10 acted as acute phase proteins

treatment

incorticosteroids.

severe

was associated Recently,

with a significant

importanttisone

implications

for reducing

the high CAP

mortality.

Figure 2. Meta-analysis for the association

between

mortality

and

a multicenter

that the excess

of IL-6 and IL-10 wasDuringreduction

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047926.g002

infectious pneumonia,

inflammatory

cytokines,

such

as

in mortality. A retrospective study conducted

byConfalonieri

Garciaperformed by

interleukin

(IL)-6,

IL-8

and

IL-10

acted

as

acute

phase

proteins

ality rate in CAP [4]. Corticosteroids

tisone

in who

severe

Vidal

etshowed

al.

[9]that

found

thatofmortality

decreased

in thetreatment

patients

[3]. Ainrecent

study

themetabolic

excess

IL-6 and gastroduodenal

IL-10

was

disorders,

bleeding,

muscle

weakness,

replacement therapy might be effective

critical

illness,

including

reduction in mortality. A re

widely usedsevere

anti-inflammatory

drugs.

and

Previous

study Vidal

found ettreatment

that

corticosteroids

CAP. In subgroup analysis

by the duration

corticosteassociated

with a of

high

mortality rate

in superinfection.

CAP [4].

Corticosteroids

received

systemic

steroids

along

with antibiotic

al. [9]

found for

that m

increased

the

risk

of

hyperglycemia

and

hypernatremia

[23].

In

roids

treatment,

we

found

that

prolonged

corticosteroids

treatment

are the most

effective

and

widely

used

anti-inflammatory

drugs.

ed the association of glucocorticoids

received

systemic

steroids

severe

CAP.

Moreover,

results

from

a

systematic

review

showed

addition, there was no evidence for an increased risk of bleeding,

(.5 days) was associated with a greater benefit compared with

g

An early study demonstrated the association of glucocorticoids

severe CAP. Moreover, re

superinfection, or neuromuscular weakness [23]. In our metaanalysis, treatment with corticosteroids in CAP was associated with

an increased risk of hyperglycemia,

was not associated Octob

with

17 but

October

2012

|

Volume

|

Issue

10

|

e47926

gastroduodenal bleeding and superinfection. However, we could

not address the association between treatment with corticosteroids

and risk of hypernatremia or neuromuscular weakness. It was due

to insufficient information can be extracted from primary

publications. Further studies should be designed to analyze these

issues. Hyperglycemia occurred frequently in corticosteroids

treatment courses less than 5 days. Recently, Annane et al. [23]

assessed the use of corticosteroids for severe sepsis and septic shock

in a systematic review. They showed

that hydrocortisone

for a

PLOS ONE

| www.plosone.org

1

prolonged duration (.5 days) may improve survival in severe

sepsis and septic shock [23]. Moreover, a study on acute

respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) suggested that more than

7 days corticosteroids strategy led to reduction in markers of

inflammation, duration of mechanical ventilation, and intensive

care unit stay [31]. Therefore, the beneficial effect of prolonged

on. For these and other

a specific time window

ould be recommended.

therapy should be addiagnosis is considered

dicated that antibiotic

as also associated with

re even more concerns

biotic when the patient

2

NOTE. Criteria are from [268, 274, 294]. pO2, oxygen partial pressure.

a

Important for discharge or oral switch decision but not necessarily for

determination of nonresponse.

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Lionel A. Mandell, Div. of

McMaster University/Henderson Hospital, 5th Fl., Wing

at a predetermined time, regardless of the clinical

response

Concession

St., Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

This was

official

statement of the Infectious Diseases Society

[269]. One study population with nonsevere illness

ranand intravenous

the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approved by

domized to receive either oral therapy alone or

Directors on 5 November 2006 and the ATS Board of Directo

therapy, with the switch occurring after 72 h without fever. The

2006.

study population with severe illness was randomized

to receive

a

Committee

cochairs.

Downloaded from http://cid

apy has adverse consey ill, hemodynamically

should be encouraged,

s recommendation. Deing the transition from

ith the frequent use of

d communication issues

tibiotics for 18 h after

that the best and most

the initial dose be given

acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the f

different organizations, and several hav

guidelines for management of CAP. Two

widely referenced are those of the Infect

Society of America (IDSA) and the Ameri

Society (ATS). In response to confusion r

Table 10. Criteria for clinical stability.

ferences between their respective guidelin

and the ATS convened a joint committee

Temperature !37.8!C

unified CAP guideline document.

Heart rate !100 beats/min

Respiratory rate !24 breaths/min

The guidelines are intended primaril

Systolic blood pressure "90 mm Hg

emergency

Arterial oxygen saturation "90% or pO "60 mm Hg

on room air medicine physicians, hospital

Ability to maintain oral intakea

mary care practitioners; however, the ext

a

Normal mental status

ture evaluation suggests that they are al

either intravenous therapy with a switch to oral therapy after

Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 44:S27–72

2 days or a full 10-day course of intravenous antibiotics.

! 2007 by Time

the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All r

to resolution of symptoms for the patients with1058-4838/2007/4405S2-0001$15.00

nonsevere ill-

NAC

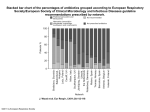

PREVENCION 250

PCV-7 vaccine

introduced

Age

<1 year

1 year

2 years

3 years

Rate per 100 000 population

200

150

100

50

0

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

Year

Figure 1: Incidence of pneumococcal disease in children in the USA before and after introduction of the

PCV-7 vaccine

PCV-7=conjugate seven-valent pneumococcal vaccine. Reprinted with permission.17

within urban neighbourhoods. Similar small-scale

outbreaks have been reported in day-care centres, jails,

military bases, and men’s shelters.10–12 Airway colonisation

by pneumococci is readily detectable in about 10% of

healthy adults. 20–40% of healthy children are carriers,

decreased overall incidence

rise in invasive pneumococc

serotypes.18 This pattern see

prompted a renewed in

formulations. Incidence rate

per 100 000 per year in isola

such as Alaskan Eskimos,

the Maoris of New Zealand.

Other recognised risk fa

coccal disease in children a

alcoholism, diabetes mellitu

underlying lung disease, se

and probably other respirato

and complement deficien

compromised states, includi

recent acquisition of a virul

smoking, proton pump in

factors probably contribute

(panel).3,14 Antecedent respi

exposure to antibiotics seem

for colonisation of airways

disease. Antibiotic-induced

inhibitory bacteria (α-ha

particular), release of vira

neuraminidase) that prom

inflammation-induced exp

invasion receptors on host ce

factor receptor21 and CD14,22

colonisation and invasion.

Table 13.

Recommendations for vaccine prevention of community-acquired pneumonia.

Factor

Pneumococcal

polysaccharide vaccine

Inactivated

influenza vaccine

Route of administration

Type of vaccine

Intramuscular injection

Intramuscular injection

Bacterial component (polysaccha- Killed virus

ride capsule)

Recommended groups

All persons !65 years of age

All persons !50 years of age

High-risk persons 2–64 years of

age

High-risk persons 6 months–49

years of age

b

Current smokers

Household contacts of high-risk

persons

Health care providers

Chronic cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, or liver disease

Diabetes mellitus

Children 6–23 months of age

Chronic cardiovascular or pulmonary disease (including

asthma)

Chronic metabolic disease (including diabetes mellitus)

Cerebrospinal fluid leaks

Alcoholism

Renal dysfunction

Hemoglobinopathies

Asplenia

Immunocompromising conditions/medications

Immunocompromising conditions/medications

Native Americans and Alaska

natives

Long-term care facility residents

Compromised respiratory function or increased aspiration risk

Pregnancy

Residence in a long-term care

facility

a

Downloaded from http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Costa Rica on August 31, 2014

Specific high-risk indications for

vaccination

acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the f

different organizations, and several hav

guidelines for management of CAP. Two

Live attenuated

widely

referenced are those of the Infect

influenza vaccine

Intranasal spray

Live virus

Society of America (IDSA) and the Ameri

Healthy persons 5–49 years of

In response to confusion r

age,Society

including health(ATS).

care

providers and household contacts of high-risk persons

ferences between their respective guidelin

and the ATS convened a joint committee

unified CAP guideline document.

Avoid in high-risk persons

The guidelines are intended primaril

emergency medicine physicians, hospital

mary care practitioners; however, the ext

ture evaluation suggests that they are al

Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Lionel A. Mandell, Div. of

McMaster University/Henderson Hospital, 5th Fl., Wing

Revaccination schedule

One-time revaccination after 5

Annual revaccination

Annual revaccination

Concession St., Hamilton, Ontario L8V 1C3, Canada (lmandel

years for (1) adults !65 years

of age, if the first dose is reThis official statement of the Infectious Diseases Society

ceived before age 65 years; (2)

persons with asplenia; and (3)

and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approved by

immunocompromised persons

Directors on 5 November 2006 and the ATS Board of Directo

NOTE. Adapted from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [304].

Avoid use in persons with asthma, reactive airways disease, or other chronic disorders of the pulmonary or cardiovascular systems; persons with other

2006.

underlying medical conditions, including diabetes, renal dysfunction, and hemoglobinopathies; persons with immunodeficiencies

or who receive immunosuppressive therapy; children or adolescents receiving salicylates; persons with a history of Guillain-Barré syndrome; and pregnant women.

a

Committee

cochairs.

Vaccinating current smokers is recommended by the Pneumonia Guidelines Committee but is not currently an indication for vaccine according