* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Bionic Ear

Speech perception wikipedia , lookup

Auditory processing disorder wikipedia , lookup

Telecommunications relay service wikipedia , lookup

Lip reading wikipedia , lookup

Hearing loss wikipedia , lookup

Sound localization wikipedia , lookup

Olivocochlear system wikipedia , lookup

Noise-induced hearing loss wikipedia , lookup

Evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles wikipedia , lookup

Audiology and hearing health professionals in developed and developing countries wikipedia , lookup

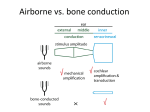

The Bionic Ear Iona Ross, Biomedical Engineering, University of Rhode Island BME 281 First Presentation, October 18, 2011 <[email protected]> H impairment is a worldwide problem. According to Hearing International, more than 600 million people in the world are considered “hard of hearing” and about 250 million people worldwide have moderate to severe deafness. The way that we hear is by use of the three parts of the ear. The most external part, known as the pinna, “collects” and “directs” sound through the ear canal to the ear drum membrane. The ear drum detects these sounds, and sends vibrations to the ossicles which amplify the sounds and send them to the inner ear. The inner ear, or cochlea, then transmits these vibrations along the auditory nerve with help of electrical stimulation from the brain. In people that have a problem hearing, there is a malfunction in this process. For some people, sound cannot even reach the inner ear. These people suffer from conductive deafness. Those that suffer from sensori-neural deafness experience problems with the transmission of signals to the brain from the cochlea. This is more common and is abetted by the bionic ear. EARING Experimentation with hearing began in the 19th century with two scientists, Count Volta and Frenchman, Duchenne of Boulogna. Both stimulated hearing using electricity. In 1957, two scientists, Djorno and Eyries, implanted a single electrode attached to an induction coil into the head of a patient in order to stimulate hearing. The result was a brief perception of sound. Throughout the 1960s and into the1970s, continued research on stimulated hearing was conducted and the findings indicated that a multiple electrode output would best stimulate the auditory nerve of a person, and best enable the person to hear again. Using this information, Australian professor, Dr, Graeme Clark, was able to produce the first template for today’s “bionic ear.” In 1978, his product was inserted into Rod Saunders and Saunders was able to hear sound. Professor Clark’s original bionic ear, made with help from researchers at the University of Melbourne, the federal government, and a “medical equipment exporter” called “Nucleus” was dubbed the Nucleus® 22 Cochlear Implant System. The latest cochlear implant on the market is the Nucleus® 24 Cochlear Implant System. Just like the previous system, the Nucleus® 24 has two internal components: an array of electrodes and the receiver-stimulator, and three external components that are worn by the person: the microphone, the speech processor, and the transmitting coil. How the cochlear implant works is that it essentially “replaces the function of the ear”, via stimulation of a person’s “remaining hearing nerves.” In short, sound is detected by the microphone, “sent” to the speech processor where it is transformed into electrical code and sent via a cable to the transmitting coil. From the radio waves of the transmitting coil, the electrical code travels through the skin to the implant. “The implant package decodes the signal” and the required amount of current is sent to the different electrodes within the cochlea. Once these nerve endings have been stimulated, “the message is sent to the brain along the auditory nerve” and sound is heard by the person. The other fascinating part of the Nucleus® 24 is the NRT tool technology, or neural response telemetry, it contains. This tool is able to record neural responses and can non-invasively and quickly inform an audiologist if the cochlear implant is appropriately stimulating the hearing fibers of the inner ear. Research on cochlear implants is still very much young in the world of science. As of right now, even the Nucleus® 24 Cochlear Implant System cannot improve everyone’s hearing. The system has been able to help the majority of those that lose their hearing as a result of age, however it has a difficult time helping young children who are hearing impaired at birth. A main goal of the future for scientists is to expand the population in which they can help with a cochlear implant. It is also to improve upon the clarity of the signals sent to the brain so that patients have an easier time recognizing what they hear. Scientists also want to make the cochlear implant more convenient for people by making the entire device internal. Research is being done as of right now to implant the microphone. Work is also being done to improve the cost of a cochlear implant for people. As of right now, the implant costs thousands of dollars, not including the appointments needed to be made with audiologists before and after the procedure. The hope of scientists is to make the device more affordable in the future. REFERENCES [1] Australian Academy of Science. “Cochlear Implants – wiring for sound”. 2009.<http://www.science.org.au/nova/029/029box03.htm>. [2]Traynor, Bob. “The Incidence of Hearing Loss Around the World” 6 April2011.<http://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearinginternational/2011/incidence-ofhearing-loss-around-the-world/> [3]ThePowerhouseMuseum\<.http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/hsc/cochlear/the_coc hlear.htm>.I USED SEVERAL ARTICLES FROM THIS SITE. [4] “Cochlear Implantation and Quality of Life in Deafness”. Damen, G. W. J. A.,Mylanus E.A.M, Snik A.F.M. Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures.< http://www.springerlink.com/content/h1q077560x44v93l/>.