* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Why Do We Say That?

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Germanic weak verb wikipedia , lookup

Classical compound wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

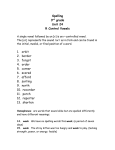

Welcome Welcome Why Do We Say That? The The Indo-European Indo-European Factor Factor IE: 4000-2500 B.C. Inherited Inherited Word Word Stock Stock Indo-European vocabulary correspondences English German Gothic (Old Gmc) Latin Greek night (OE niht) Nacht nahts eight (OE eahta) acht ahtau nox, noctis octo≠ nyktós (G.) okto≠ nák, naktam as˝t¸au Old Indic (Sanskrit) Old Irish -nocht ocht (Old) Welsh nos oeth Lithuanian naktis a£tuonì Old Slavic no£t@ osm@ garden (OE geard) Garten gards ‘house hortus xórtos ‘court’ grhá‘house’ gort garth ‘enclosure’ gar~das ‘enclosure’ gradu` guest (OE giest) Gast gasts meal (OE melu) mahlen malan hostis molere mane (OE manu) Mähne mana (OHG) mon|le ‘neckband’ m¥llo≠ mrn˝a≠ti melim malu mánya≠ ‘neck’ muin ‘neck’ mwn ‘neck’ malù gost@ meljoˆ monisto ‘neckband’ Vowel Vowel Gradation Gradation ((Ablaut Ablaut)) Indo-European made frequent use of vowel gradation (Ablaut) to indicate tenses and various forms of words. Its effects live on in the daughter languages and beyond. From IE st(H)\-/st(H)a≠- ‘stand’: Lat. sta≠re OE standan, MnE stand (with present -n- infix) Lat status, OE sto≠d, MnE stood (from perfect stem) From PrGmc sta∂iz: E stead, G Stadt, Statt, Stätte Skt sthíti ‘(the act of) standing’ Lat statio≠, stationis, Gk stásis OE sto≠d ‘group of animals, esp. for breeding’ > MnE stud, Ger Stute Also E stall < Gmc sta∂laz; E stool, Ger Stuhl, Rus stol ‘table’, Gk ste≠le≠ ‘column’ Possibly E stem, G Stamm Zero grade -st-: nest Vowel Vowel Gradation Gradation ((Ablaut Ablaut)) Why do we say SING - SANG - SUNG or WRITE - WROTE - WRITTEN? Vowel Vowel Gradation Gradation ((Ablaut Ablaut)) Indo-European vowel gradations were of two types qualitative (e.g., a/o, a/e,) quantitative (e.g., a/a≠, o/o≠, a/Ø that is, zero-grade) Germanic retained the alternations very visibly in the verb system, with original IE vowels changed slightly but regularly in some instances. Gothic, the oldest Gmc language for which we have extensive records, shows the most regular pattern and is used to mirror the PrGmc situation. German and English exhibit variations due to sound changes and the effects of analogy. Vowel Vowel Gradation Gradation ((Ablaut Ablaut)) Traditional verb class I PrGmc pres | Gothic steigan ‘rise’ OHG tr|ban ‘drive’ OE b|tan ‘bite’ pret1 ai stáig treib ba≠t pret2 i stigum tribun biton p.p. i stigans gitriban biten Traditional verb class II PrGmc pres eu Gothic kiusan OHG sliofan ‘slip’ OE be≠odan ‘command’ pret1 au kaus slouf be≠ad pret2 u kusum sluffun budon p.p. u kusans gisloffan boden Vowel Vowel Gradation Gradation ((Ablaut Ablaut)) Traditional verb class IV PrGmc pres e Gothic baíran (pron ‘e’) OHG stelan ‘steal’ OE beran ‘bear’ pret1 a bar stal bær pret2 æ≠ be≠rum sta≠lun bæ≠ron p.p. o baúrans gistolan boren Traditional verb class V PrGmc pres e Gothic qiπan OHG geban ‘give’ OE metan ‘measure’ pret1 a qaπ gab mæt pret2 æ≠ qe≠πum ga≠bun mæ≠ton p.p. e qiπans gigeban meten Preterite-Presents Preterite-Presents Preterite-present verbs have past-tense (preterite) forms for present-tense meanings. These verbs are ancient, all the way from IE days. In Germanic languages, as we have seen, preterite tenses had two different vowel gradations. In OE: OE singan: ic/he≠ song I/he sang πu≠ sunge (thou sangest) we≠/ge≠/he≠o sungon we/ye/they sang Preterite-Presents Preterite-Presents In Germanic languages, preterite tenses had two different vowel gradations: OE singan: ic/he≠ song I/he sang πu≠ sunge (thou sangest) we≠/ge≠/he≠o sungon we/ye/they sang The OE verb witan (to know) uses similar forms with a present meaning: OE witan: ic/he≠ wa≠t I/he know(s) orig. ‘I have seen’ πu≠ wite we≠/ge≠/he≠o witon we/ye/they know PRESENT meaning ! Preterite-Presents Preterite-Presents Preterite-present witan (to know) came from IE. OE witan: wa≠t - witon know Originally meant way back in IE ‘I have seen’, the perfect (past) tense. If I have seen something, I ‘know’ it. In form it is thus past, but came to have a present meaning. It is related to Lat video≠, vide≠re ‘see’’! Cf. also Russian vizhu, vidit, ‘I see, she sees’ Preterite-Presents Preterite-Presents Preterite-presents are largely modal auxiliary verbs: Eng can OE can/cunnon G kann/können shall sceal/sculon soll/sollen may mæg/magon mag/mögen will wille/willa∂ will/wollen must mo≠t/mo≠ton muss/müssen (durst) πearf/πurfon darf/dürfen OE (mostly) retained the two-vowel past tense system in these ancient verbs (but of course with PRESENT meaning). Modern German still does as well, but ONLY in the modal verbs and wissen (OE witan). MnE has leveled them out to one vowel only. Preterite-Presents Preterite-Presents Modern English, by way of Middle English, has ended up with just one vowel. In the case of witan, we have the remains of the verb ‘to know’ in: witless ‘having no sense, knowing nothing’ unwittingly ‘without knowing’ witness > OE witnes ‘knowledge; testimony’ witling ‘person of little wit’ dull-witted, dim-witted ‘weak in the knowledge department’ Preterite-Presents Preterite-Presents More modern traces of witan ‘to know’: nitwit ‘know-nothing’ (or ‘brain the size of a louse’s egg’) witty (formerly, ‘having great knowledge’) wits (brains, knowledge) at one’s wits’ end ‘not knowing what to do’’ to wit ‘so that you know’, for example wittol (ME wetewold): an archaic term for a cuckold, one who knows of his wife’s infidelity but does nothing about it More More vowel vowel gradation gradation Do these vowel gradations only show up in verbs? More More vowel vowel gradation gradation The IE Connection: not only verbs fare drive Gk po≠s ‘foot’ ferry drift foot, Ger Fuß wayfarer in droves Lat pe≠s, pedis ford pedal, podium, firth tripod; in fetters Ties Ties that that bind: bind: ProtoProtoGermanic Germanic Ties that bind: Proto-Germanic Development Development of of Germanic Germanic Proto-Gmc: 500 B.C. - 3C A.D. PreGmc: 2500-500 B.C. Germanic Germanic Tribes Tribes Off to Merry Olde England! (beginning around 400-450 A.D.) IE IE to to Germanic Germanic How did the Germanic language family become different from Indo-European? What kinds of factors made it a different language family? IE IE to to Germanic Germanic First Sound Shift: consonant changes: IE bh, dh, gh > Gmc b≠, ∂, ©, later b, d, g in some positions IE p, t, k > Gmc f, π, x (h initially) IE b, d, g > Gmc p, t, k Relatively complicated IE verb system simplified in Germanic to present and past tenses only. (Compound tenses added later.) Vowel changes: IE o > Gmc a (L octo≠, Go ahtau) IE a≠ > Gmc o≠ (L ma≠ter, OE mo≠dor) Dental preterite (past tense formed by a t/d/π suffix) was a Gmc innovation: origin of MnE -ed, now in the vast majority of our verbs IE accent could be on any syllable; the accent became fixed on the first syllable in Germanic Some vocabulary not found in other IE languages Germanic Germanic Sound Sound Shift Shift Examples of First Germanic Sound Shift Separated Germanic from other IE branches Germanic changes shown in red in chart IE bh > L f, Gk ph Gmc b fra≠ter / brother fiber / beaver fra(n)go≠ / break Gk pho≠gein / bake IE/L/Gk p > Gmc f pater / father piscis / fish portus / ford pullus / foal ped- / foot pecu ‘cattle’ / fee OE feoh IE/L/Gk b > Gmc p G kannabis / hemp turba / thorp ‘town’ (IE b was very rare; little evidence left of it) IE dh > L f, Gk th Gmc d fi(n)gere ‘mold’ / dough (OE d|ge) foris / door Gk thygate≠r / daughter IE/L/Gk t > π tre≠s / three tu≠ / thou tenuis / thin tume≠re ‘swell’ / thumb tona≠re / thunder IE/L/Gk d > Gmc t duo≠ / two dent- / tooth doma≠re / tame decem / ten edere / eat IE gh > L h, Gk ch Gmc g hostis / guest hortus / geard homo / OE guma (cf. ME bridegome) Gk chole≠ / gall IE/L/Gk k > Gmc h cornu≠ / horn cord- / heart quod / hwæt, what cent- / hund-red capere / heave, have canis / hound IE/L/Gk g > Gmc k genu / knee ager ‘field’ / acre genus / kin G gyne≠ / queen gra≠num / corn Dental Dental preterite preterite If we inherited a system of vowel alternations from Indo-European, why do we put -ed on most of our verbs to form the past tense without changing the vowel at all? Dental Dental preterite preterite Dental suffix to form past tense/past participle Examples from Germanic languages Gothic OHG OE MnE MnG Dan Ice Infinitive / 3s past / past participle nasjan/nasida/nasiπs ‘save’ haban/habáida/habáiπs ‘have’ nerien(nerren)/nerita/ginerit habe≠n/habe≠ta/gihabe≠t fremman/fremmede/fremed ‘perform’ habban/hæfde/hæfd save/saved/saved have/had/had keep/kept/kept rip/ripped/ripped retten/rettete/gerettet haben/hatte/gehabt spise/spiste/spist ‘eat’ have/havde/haft bo/boede/boet ‘live, dwell’ dæma/dæmdi/dæmdur ‘deem’ hreyfa/hreyf∂i/hreyf∂ur ’move’ her∂i/herti/hertur ‘harden’ bor∂a/bor∂a∂i/bor∂a∂ur ‘eat Fixed Fixed Accent Accent Greek retained IE movable accent: Gmc (here OE) fixed accent on first syllable: Nom Gen Dat Acc Voc pate≠r Sing. patros patri patera pater N/D/A fæder Sing. Gen fæder(es) N/V Gen Dat Acc pateres Plur. patero≠n patrasi pateras N/A Gen Dat fæderas Plur. fædera fæderum This was to have dramatic effects in Middle English. Fixed Fixed Accent Accent Compare these words from Old English, featuring full vowel values in unstressed syllables, with their Middle English equivalents: Old English ‘lame’ lama ‘go, fare’ faran, p.p. faren ‘stone’ sta≠nes (G), sta≠nas (pl) ‘falleth’ fealla∂ nacod ‘we made’ macodon ‘sure’ sicor leng∂o ‘liquor’ medu Middle English la≠me fa≠ren (both forms) sto≠ˆnes* falleth na≠ked ma≠keden se≠ker lengthe me≠d ˆ e Unaccented vowels were leveled to the neutral -e. *In Middle English, the final -s came to be a plural signal. *It also retained its previous function of marking the genitive. Verner’s Verner’s Law Law Why do we say I WAS but YOU WERE? Verner’s Verner’s Law Law When the original IE accent FOLLOWED a syllable with Gmc voiceless f, π, x and s were VOICED to b≠(v), ∂, g, z (which by OE had become r). Similar things happen in modern English and German. Compare: accent before accent after causes voicing MnE éxecute (ks) exécutive (voiced to gz) Ger Hannoveráner (voiced to v) Hannóver (f) Verner’s Verner’s Law Law IE,PrGmc: Voiceless Accent + f, π, x, s cf. Skt vavárta, OE wearπ Voiced b≠(v), ∂(d), g, z(r) + Accent Skt vavrtimá, OE wurdon Effects of Verner’s Law frequent in past tense plural and past participle of verbs; accent used to be AFTER f, π, x, s in these forms: OE fre≠osan ‘freeze’, ce≠osan ‘choose’ se≠o∂an ‘seethe’ fle≠on ‘flee’ sn|∂an ‘cut’ fe≠olan ‘reach’ se≠on ‘see’ be≠on, wesan PAST fre≠as / fruron ce≠as / curon se≠a∂ / sudon fle≠ah / flugon sna≠∂ / snidon fealh / fulgon seah / sæ≠gon wæs / wæ≠ron PP froren coren soden flogen sniden fulgen segen Modern English has (sensibly?) eliminated all but was/were. Mutating Mutating Vowels! Vowels! Why do we say stone-stones, friend-friends, but goose-GEESE, mouse-MICE, foot-FEET? Mutating Mutating Vowels! Vowels! OE vowels High |, y≠ u≠ y, i Front u e≠ o≠ e o æ a≠ æ Low a Back Mutating Mutating Vowels! Vowels! In PreOE (PrGmc), base vowels are fronted (or just raised for æ>e) if |, i or j (semivowel as in yes) were in the following syllable. High y≠ u≠ y Front u e≠ o≠ e o æ Back a≠ æ a Low The vocal organs anticipate the high front position of |, i or j . Mutating Mutating Vowels! Vowels! The effects of the earlier |, i or j remain by evidence of the changed stem vowel. The mutation factor is usually lost by the time of OE, appearing to be an exception unless you look back earlier. The umlaut factor often caused doubling of the consonant before disappearing, an additional ghost of its former presence. Gothic, for instance, shows us the closest information we have to Proto-Germanic: Gothic example Old Engl/Modern Engl reflex (vowel unmutated) (showing mutated vowel) certain verb classes nas-j-an ‘save’ sat-j-an ‘set, cause to sit’ at-j-an haf-j-an comparative & superlative suffixes: -iz-, -ist- (alπiza) but no umlaut if -o≠z-, -o≠st- nerian set (from past tense), OE settan etch (‘eat away at’), Ger ätzen OE hebban, MnE heave old,elder,eldest; < eald,ieldra,ieldesta sceort, sciertra, sciertesta BUT: fægen, fægenra, fægnosta ‘fain, glad’ Mutating Mutating Vowels! Vowels! Gothic example (vowel unmutated) Old Engl/Modern Engl reflex (showing mutated vowel) certain noun classes cf. PGmc *bo≠k, pl. *bo≠kiz fo≠tus, fo≠tjus (PGmc pl *fo≠tiz) mouse/mice, louse/lice (OE mu≠s > pl. my≠s > m|s > mice) goose/geese, foot/feet Umlaut is essentially inactive in modern English. Its remains are viewed as “irregularities” now. As a side note, modern Icelandic is in contrast to English so conservative that it has retained full case inflections from ON. Phonological processes like umlaut remain very much alive to this day. These nouns, for instance, alternate 2 or even 3 vowels: ‘tooth’ NGA tönn, G tannar; (pl.) NA tennur, G tanna, D tönnum ‘foot’ N fótur, G fótar, D fæti, A fót; (pl.) NA fætur, G fóta, D fótum Mutating Mutating Vowels! Vowels! In summary, the combination of original ablaut (vowel gradation) from Indo-European and the effects of umlaut factors (i-, u-, w-mutation and some other factors)--plus a few later developments having to do with syllable structure--all serve to create the vowel alternations we see today in various word families. broad/breadth (OE bra≠d!) long/length wide/width fall, fell, fallen; to fell a tree heave, hove; have; heft, hefty give, gave, given; gift etc. etc. etc. Alliteration Alliteration ((Stabreim) Stabreim) Why do we say things like FRIEND or FOE? Alliteration Alliteration ((Stabreim) Stabreim) In Old Germanic oral tradition, alliteration (Ger. Stabreim), or repetition of initial sounds in successive words, was common instead of rhyme as we think of it. Alliteration served: As a memory aid For dramatic effect, emphasis on important words Alliteration Alliteration ((Stabreim) Stabreim) An example from Beowulf (translation by Seamus Heaney): Ongeat πa≠ se go≠da grund-wyrgenne, mere-w|f mihtig; mægen-ræ≠s forgeaf hilde-bille, hond sweng ne ofte≠ah πæt hire on hafelan hring-mæ≠l a≠go≠l græ≠dig gu≠∂-le≠o∂. (...) The hero observed that swamp-thing from hell, the tarn-hag in all her terrible strength, then heaved his war-sword and swung his arm: the decorated blade came down ringing and singing on her head. (...) Alliteration Alliteration ((Stabreim) Stabreim) The mindset of Germanic alliteration survives in many alliterative pairs, some of which are modern formations: kith and kin time and tide friend or foe rough and ready with heart and hand wind and weather life and limb down and dirty bed and breakfast rest and relaxation tried and true now or never live and learn hippety-hop house and home vim and vigor no rhyme or reason hale and hearty come hell or high water Word Word Order Order Why do we hear things in strange orders in nursery rhymes that we’d never say normally? You know, like A merry old soul was he. and Then came his fiddlers three. Word Word Order Order Although Subj-Vb-Obj was a typical word order in Gmc., and very much so already in Old English, placing another element first was common, especially since the inflections indicated grammatical function. The verb then usually remained second if for instance an adverb came first: ˜a≠ clipode he≠ and cwæ∂ ... Then called he and said ... (MnE: Then he cried out, saying) ... Word Word Order Order Modern English retains the V-S inversion only in a few fixed expressions: “Give me wine!” said he. (Old King Cole?) Little did we know that a cliff lay ahead. Not only was she rich, but she was also smart. Never would I presume! No sooner had he said it ... Otherwise, the S-V order prevails. Modern English, with no inflections, relies solely on word order to indicate grammar function. Soon they saw a clearing ahead. “Give me some wine!” he said. Word Word Order Order The V-S inversion was also typical in older English for questions with question words: Hu≠ clypode A±beles blo≠d to≠ Gode ... ? ‘How called out Abel’s blood to God ... ?’ As well as in yes/no questions: Gehy≠rst πu≠, sæ≠lida? ‘Hear you, sailor?’ Word Word Order Order Modern English retains the V-S inversion in all questions, but most often inserts a helping verb: not How called out Abel’s blood to God ... ? but How did Abel’s blood call out to God ... ? As well as in yes/no questions: not Hear you, sailor? but Do you hear, sailor? Word Word Order Order Generally, only auxiliary verbs (used with infinitives or participles as completions) are allowed to form a V-S inversion in Modern English questions: OK OK OK OK Can you bring me some tea? Must they always shout so much? Have you forgotten anything? Is Mrs. Jones coming to the social? but Have you any change? seems quaint (or British!), and Wish you anything else, Sir? or Brought Tom the pizza? sound downright wrong in MnE. Semantic Semantic shift shift OK, so, if German, Dutch, Danish and English all came from the same source, why does tide mean a different thing in English from the other three, even though they were originally the same word? English tide (regular ebb and flow of the sea) Danish tid (= time) Dutch tijd (= time) German Zeit (= time) OE t|d also meant ‘time, hour’ and survives in such words as Yuletide, Whitsuntide, or “time and tide will admit no delaying” (an alliterative doublet) Semantic Semantic shift shift Many times words change their meanings slightly or a great deal over centuries. This is semantic shift. MnE deer // G Tier, Du dier, OE de≠or ‘animal’ MnE wife - OE w|f ‘woman, wife’ // G Weib, Du wijf (now pej.) Ice hross, MnE horse // G Ross, Du ros, ‘steed’ MnE town - OE tu≠n ‘enclosure, village’ // G Zaun ‘fence’ // Du tuin ‘garden’ // OIr du≠n ‘fortress’ Frequent as -ton in English place & personal names: Brighton, Newton, Flemington, Wellington, etc. NWGmc NWGmc & & Ingwaeonic Ingwaeonic What’s the origin of bring vs. brought? NWGmc NWGmc & & Ingwaeonic Ingwaeonic North Sea dialects (e.g., OE, Dutch, Frisian) shared certain characteristics. One was loss of nasal consonants (n, m) before a fricative sound. The vowel was lengthened in compensation for the loss. Ingwaeonic OE *finf > f|f, MnE five, Du vijf cf. Ger fünf bring vs. brought (g was fricative) think vs. thought (k<x,h) stand vs. stood OE so≠π (MnE forsooth) cf. Dan sand OE *tanπ > *tonπ > to≠π, tooth G Zahn (cf. Lat dent-) OE *monπ > *munπ > mu≠π > mouth G Mund (cf. Lat mand-) Here Dutch has tand and mond (WITH the n). Why? Second Second Sound Sound Shift Shift Why does German seem so different from English when it’s a related language? (You knew I had to sneak German into this, didn’t you!) Second Second Sound Sound Shift Shift All Germanic languages shared the First Sound Shift. That’s how they split off from Indo-European. Only Central and Southern German underwent something called the Second (or “High German”) Sound Shift which further differentiated it from the remaining Germanic languages--including, incidentally, northern German dialects. This “Zweite Lautverschiebung” occurred most completely in remote Swiss mountain villages and spread northward. Only some of the sounds shifted in central Germany--or only in some words and not others--so those dialects are a “mix” of shifted and unshifted sounds. The process happened around 400-800 A.D. Second Second Sound Sound Shift Shift As with the First (Germanic) Sound Shift, consonants were affected in the Second (High German) Sound Shift: English Dutch ten, two water, that pepper, deep make, book tien, twee water, dat peper, diep maken, boek German (showing 2nd shift) zehn, zwei Wasser, das Pfeffer, tief machen, Buch Northern German dialects, along with Frisian and Dutch, are more akin to English in their consonants. In fact, Frisian is the closest relative to English. Latin Latin Leftovers Leftovers If Latin was so important in Europe until well into the 18th and even 19th centuries, did English absorb any Latin vocabulary? Latin Latin Leftovers Leftovers Latin loan words (examples from Pyles) early loans: common to all Gmc languages oral loans, popular language wine (OE w|n), Lat v|num cheap (EmnE good cheap, OE ce≠ap ‘marketplace, wares, price’; cf. name Chapman), Lat caupo≠ ‘tradesman, wineseller’ Latin Latin Leftovers Leftovers anchor (OE ancor), Lat ancora butter (OE butere), Lat bu≠tyrum chalk (OE cealc), Lat calccheese (OE ce≠se), Lat ca≠seus cf. Ger Käse, Frisian tji dish (OE disc), Lat discus cf. Ger Tisch ‘table kettle (OE cetel), Lat catillus ’little pot’ cf. Ger Kessel’ kitchen (OE cycene), L coqu|na cf. Ger Küche mile (OE m|l), L milia (passuum) ‘a thousand (paces)’ mint (OE mynet ‘coin, coinage’), L mone≠ta cf. Ger Münze -monger (OE mangere ‘trader, merchant, broker’), L mango≠ cf. gossip monger, war monger mongrel is not from this root; probably from OE gemong ‘crowd’ > ME ymong, mong ‘mixture’ pepper (OE piper, pipor), L piper cf. Ger Pfeffer pound (OE pund), L pondo≠ ‘measure of weight’) cf. Ger Pfund sack (OE sacc), L saccus) sickel (OE sicol), L secula’ cf. Ger Sichel street (OE stræ≠t), L (via) stra≠ta ‘paved (road) cf. Ger Straße wall (OE weall), L vallum These were all borrowed into Gmc after the first sound shift but before the second “High German” sound shift, as shown by German equivalents of indicated words. Latin Latin Leftovers Leftovers Pyles lists as earlier loans (some acquired from British Celts): Old English tæfl ‘gaming board’ candel sealtian ‘to dance’ sealm leahtric ‘lettuce’ eced ‘vinegar’ Læden ‘Latin’ mægester ‘master’ cest ‘chest’ peru ‘pear’ senop ‘mustard’ regol ‘rule’ mynster ‘monastery’ earc ‘ark’ t|gle ‘tile’ sicor ‘secure’ stær ‘history’ segn ‘mark, banner’ (MnE sign from Fr signe, later) ceaster ‘city’ Manchester, Gloucester, Worcester, Casterton, Chesterfield, Lancaster, Exeter (< Execestre) Latin source tabula cande≠la salta≠re psalmus (from Gk) lactu≠ca ace≠tum Lat|na magister cista > cesta pirum sina≠pi re≠gula monaste≠rium arca te≠gula se≠cu≠rus historia signum castra ‘camp’ German/Dutch cognate Tafel, tafel Psalme Essig, edik/azijn Latein, latijn Meister, meester Kiste, kist/kast Birne, peer Senf, sennep Regel, regel Münster, munster Arche, ark/arke Ziegel, tegel sicher, zeker Latin Latin Leftovers Leftovers Somewhat later loans, after about 650 A.D., do not exhibt the typical English sound changes: Old English plaster alter ‘altar’ martir templ de≠mon paper messe ‘mass’ circul ca≠lend ‘month’s beginning’ come≠ta Latin source emplastrum altar martyr templum daemon papy≠rus missa > messa circulus calendae, Kalendae come≠ta German cognate Pflaster Altar Märtyrer Tempel Dämon Papier Messe Zirkel ‘compass’ Kalender Komet There are more than 500 in OE up to the Conquest; later borrowings than this from Latin are massive in number in comparison. Some of them were ultimately from Greek, from which Latin borrowed extensively. (Pyles) Latin Latin Leftovers Leftovers Middle English borrowed heavily from French and Latin. Often not really possible to tell from which language the words were taken. • ecclesiastical terms: dirge, mediator, redemptor, later Redeemer; • legal: client, subpoena, conviction; • scholarly: simile, index, library, scribe; • scientific: dissolve, equal, essence, medicine, mercury, opaque, orbit, quadrant, recipe. • verbs: admit, commit, discuss, interest, mediate, seclude; • adjectives: legitimate, obdurate, populous, imaginary, instant, complete. Pyles reports that there were hundreds of Latin words adopted between the Conquest and 1500. Latin Latin Leftovers Leftovers The most Latin and Greek terms were borrowed in the Modern English period, after 1500. From 1500-1600 or so: area, abdomen, compensate, composite, data, decorum, delirium, denominate, digress, edition, education, fictitious, folio, fortitude, gradual, horrid, imitate, janitor, jocose, lapse, medium, modern, notorious, orb, pacific, penetrate, querulous, resuscitate, sinecure, series, splendid, strict, superintendent, transition, ultimate, urban, urge, vindicate. Some of these again may be via French. From Greek via Latin: allegory, anemia, anesthesia, aristocracy, barbarous, chaos, comedy, cycle, dilemma, drama, electric, epoch, enthusiasm, epithet, history, homonym, metaphor, mystery, paradox, pharyx, phenomenon, rhapsody, rhythm, theory, zone. From Greek via French: center, chronicle, character, democracy, diet, dragon, ecstasy, fantasy, harmony, lyre, machine, nymph, pause, rheum, tyrant. From Greek directly: acronym, agnostic, anthropoid, autocracy, chlorine, idiosyncrasy, kudos, oligarchy, pathos, phone, telegram, xylophone. Celtic Celtic Carryovers Carryovers How about the Celts? After all, they had settled Britain before the Angles and Saxons, right? Celtic Celtic Carryovers Carryovers Celtic loans are not numerous because they were the conquered people. Pyles states that it is likely ceaster (< L castra) was one, as was the –coln in Lincoln (< L colo≠nia; cf. here G Köln, Du Keulen). One is torr ‘peak’. Several place names are of Celtic origin: Cornwall, Devon, Avon, Usk, Dover, London, Carlisle, and many more. A A Case Case for for Cases Cases Old dative forms: methinks, me thoughte ‘it seems/seemed to me’ me mette (ME) ‘it dreamed to me’ Old accusative: If you please ‘if it please you’ (Fr s’il vous plaît, D.O.) Old instrumental forms (OE πy≠): the more, the merrier ‘by that (much) more, by that (much) merrier nonetheless ‘nothing less by that’ all the better to eat you, my dear Old reflexive pronouns: Now I lay me down to sleep ... (myself) He set him down. = He sat (set himself) down. Prepositional Prepositional Plunderings Plunderings Why do we say “to fight WITH someone”? Aren’t we really fighting against the person? And why are thoroughbreds called that? Are they bred to be really hard workers or good at detail? Prepositional Prepositional Plunderings Plunderings wiπ in OE meant ‘against, opposite, from’: withstand ‘stand against’’ to fight with someone to break with one’s family to break up with a boyfriend withdraw ‘draw away from’’ withhold ‘hold away, back from’’ notwithstanding ‘not opposing that’ Prepositional Prepositional Plunderings Plunderings πurh (ME also πruh) gives us both ‘through’ and ‘thorough’ in the same meaning: thoroughbred ‘bred through a long line’ thorough bass ‘basso continuo’, playing all the way through the piece throughly ‘(archaic) in a thorough manner’ thoroughfare ‘passage through’ through street, throughway Old Old English English Lives! Lives! 100 most frequent words in Old English Those with little or no change in form or meaning: god mann heofon eor∂e weorold l|f lufu word weorc dæg hand cynn πanc engel ic πu≠ he≠ hit πæt hwa≠ God hwæt man πis heaven self earth hwelc world sittan life se≠can love healdan word beran work giefan day cuman hand se≠on kin be≠on, wæs thank do≠n, dyde angel go≠d I w|d thou fæst he ha≠lig it r|ce that a≠n, na≠n who he≠ah, h|erra what micel, ma≠ra much, more this mæ≠st most self, same to≠ too which eall all sit swa≠ so, as seek πæ≠r there hold πanne then bear nu≠ now give æ≠r ere, before come in, on in, on see to≠ to, toward be, was for for do, did ofer over good under under wide æfter after fast æt at holy πurh through rich and, ond and one, none gif if high, -er πe≠ah though Harder Harder to to Recognize Recognize 100 most frequent words in Old English Those with substantial change in form or meaning (modern cognate in parentheses): cyning mo≠d folc mynd do≠m fe≠ond fæsten ga≠st so≠π burg wieldan habban,hæfde mæg, meahte willan, wolde sculan, sceolde a≠gan mo≠tan, mo≠ste king (Ger. König) (mood), courage secgan (folk), people faran cunnan, cu≠∂e (mind), memory cwe∂an, cwæ∂ (doom), judgment (fiend), enemy scieppan (fastness), fortification swelc (ghost), spirit le≠of e≠ac (sooth), truth swelce (borough), walled town (wield), control a≠, na≠ have, had gel|c may, might wi∂ will, would shall, should own be able, must say (fare), travel (can, couth), know (quoth), say, said (shape), create such (lieve), beloved (eke), also (so-like), likewise aye; never, not at all like (with), against, opposite Old Old English English Doesn’t Doesn’t Live Live 100 most frequent words in Old English Those which are lost in modern English: (but not always in other Germanic languages): dryhten hyge r|ce πe≠od wuldor æ∂eling scop l|c feorh wer he≠o se≠, se≠o πe≠s, πe≠os ha≠tan, ha≠tte weor∂an beorgan witan lord, Dan. drotning thought, Dan. hygge munan dominion, Ger. Reich e≠ce sw|∂ people, nation, Ger. deutsch æ∂ele glory nobleman, prince, Ger. edel eft poet, singer ne body, corpse, Ger. Leiche πa≠ sw|∂e life mid man (but werewolf) she ac the (m. & f. forms) this (ME hight) be called, G heißen (ME worth), G werden protect, G bergen (wit), know; G wissen remember, Ice. muna eternal strong noble, G edel later, Dan. efter not, neither then, when, G da very, extremely with, G mit, Ice me∂ but The The Same Same but but Different Different Words whose meanings have changed since medieval times: now then naughty dip knave lewd crafty nice silly crude hussy harlot of no value baptize young fellow, servant uncultured wise, knowledgeable foolish, silly, wanton blessed, innocent bloody housewife drifter, no-goodnik farce stuffing; later, a filler between acts of play meat flesh compare with naught (nothing) Ger taufen Ger Knabe ‘boy’ OE læ≠wede ‘laical, ignorant’ witchcraft, know one’s craft Fr. niais ‘stupid, silly’ OE sæŁ≠lig ‘happy’, Ger selig L crudus, Fr cru ‘raw’ OE hu≠s ‘house’ Harley rider? Ha ha. OFr herlot ‘rogue’; herler ‘yell, make noise’ Fr. farcir ‘stuff’ Ger Fleisch Invading Invading Danes: Danes: Old Old Norse Norse Wasn’t there a lot of Scandinavian influence in Old English? If so, do we still see any residual effects from that? Invading Invading Danes: Danes: Old Old Norse Norse Danes and Norwegians, speaking a tongue very close in many ways to OE (Old Norse, or ON), invaded, settled and thoroughly integrated themselves into northeastern Britain starting in the 9th century. Their contact with the native population was extremely intimate, and they were assimilated into it thoroughly by intermarriage. Since ON was so closely akin to OE, many confusions and mutual influences arose between the two languages (grammar endings and syntax as well as lexical items). Invading Invading Danes: Danes: Old Old Norse Norse One visible ON element in our vocabulary is the K or SK sound, which had become a CH or SH sound in English. Interesting doublets arise: kirk / church dike / ditch skirt / shirt raise / rear shriek / screech ship / skiff Other loans from Scandinavian are: kid, get, egg skill, skin, bask sky (OE lyft, Ger Luft, Du lucht), take (OE niman, Ger nehmen, Du nemen) nay, swain Invading Invading Danes: Danes: Old Old Norse Norse Other Scandinavian loans, all part of our basic everyday vocabulary: leg, neck, skin cake, knife, window (‘wind-eye’) flat, ill, odd, ugly, wrong call, cast, die, happen, raise, take, want though An extremely important ON loan into English are the pronouns they/them. OE had a rather ill-defined mess: he/him she/her they/them OE: he≠, him, hine he≠o, hire, he≠o he≠o, him, he≠o You can see why they/them won out! (Subj, I.O., D.O.) Those Those Pesky Pesky Normans Normans Why does it seem so easy to learn many French words? They seem just like English, just pronounced differently. How did this come about? Those Those Pesky Pesky Normans Normans William the Conqueror and his band of Normans showed up in England in 1066 and took over the helm at the Battle of Hastings. They were actually Norsemen originally who had invaded northern France and been assimilated. Their language was thus French. French rulers dominatee culturally and linguistically for the next 200 years or so. French became the language of the feudal courts, church institutions, civilized life in general. Loan words reflect this cultural importance--although Norse words still enter the language faster until about 1132. ME has a vastly different look from that of OE. French French in in Public Public Life Life noble, royal, juggler, castle, prince, duke, viscount, baron government, administer, attorney, chancellor, country, court, service crime, prison, estate, judge, jury, peasant, trespass, punish, oppress, prohibit, discipline, tax, penalty, torture, supplication, exile, treason, rebel, dungeon, execution, mortgage (lit. ‘death-pledge’) abbot, clergy, preach, sacrament, vestment army, captain, corporal, lieutenant, sergeant, soldier dignity, enamor, feign, fool, fruit, horrible, letter, literature, magic, male, marvel, mirror, oppose, question, regard, remember, sacrifice, safe, salary, search, second, secret, seize, sentence, single, sober, solace carriage, courage, language, savage, village French French Sources Sources Fr gentil > gentle, later loans genteel, jaunty Loans had different forms depending on original dialect: Anglo-Norman: c-, wCentral (Parisian): ch-, gu/gchapter (L caput) cattle chattel (L capita≠le) wage gage warranty guarantee ME borrowings have ch pronounced as in OFr of the time: chase, chamber, chance, chant, change, champion, charge, chaste, check, choice Later borrowings reflect the evolved French pronunciation: chauffeur, chamois, chevron,chic, chiffon, chignon, douche, machine Those Those Pesky Pesky Normans Normans English Old French Modern French retains -s- from Old French (pronounced at time of loan) has –s(pronounced early) -s- lost in later OFr; indicated by é- school scholar strait strange stable spine spangle stallion state; estate stanch establish spouse spice spinach espy spell discourage discover scout scale (of fish) despoil describe squire, esquire escole escoler estreit, estroit estrange estable espine espingle estalon estat estanchier establir espos, espose espice, espece espinach, espinoch espier espeldre, espeler (explain) descoragier descovrir escolte (spy) escale, escaille despoillier descrire escuier école écolier (school pupil) détroit (étroit = narrow) étrange étable épine épingle (pin) étalon état étancher établir époux, épouse épice épinard épier épeler (spell) décourager découvrir écouter (listen) écaille dépouiller (skin; plunder) décrire écuyer (squire; rider) Those Those Pesky Pesky Normans Normans English Old French Modern French retains -s- from Old French (pronounced at time of loan) has –s(pronounced early) -s- lost in later OFr; indicated by circumflex forest hostel host vested beast master mistress ghastly paste pastry hospital hostage priest plaster forest hostel hoste, oste vesti beste maistre, mestre maistresse gast (ruined) past, paste pastoirie ospital ostage prestre plastre forêt hôtel (now hotel) hôte vêtu bête maître maîtresse dégât pâte pâtisserie hôpital otage (no circumflex) prêtre plâtre French French is is Fancy Fancy French words are used to describe ‘cultured’ and official life. Everyday things involved with lower classes retained the Anglo-Saxon words. Prepared meats for eating at a fine table are for instance French, as are the terms for their preparation. The animals from which the meats come are Germanic: French terms Anglo-Saxon terms beef, pork, veal, mutton, pullet; steer, pig, calf, sheep, chicken (bœuf, porc, veau, mouton, poulet) boil, broil, fry, stew, roast Also, the French terms are elegant: English ones earthy or crude: odor, perspiration, dine, deceased depart, return, desire, obtain regard, receive, urine, excrement smell, sweat, eat, dead go away, come back, want, get look at, get, ****, **** Gallic Gallic Tidbits Tidbits Rotten Row in London’s Hyde Park is from French ‘route du roi’, ‘king’s path’ (a riding path) Hoity-toity refers to upper classes looking down at lower folks from their high roof, or ‘haut toit’ Mayday! perhaps from Fr. Venez m’aider! Fun Fun Facts Facts beware: OE warian ‘preoccupy, claim the attention of’; ME war ‘on guard, attentive’ OE weard ‘guardian, keeper’ lord PrOE *hla≠f-ward ‘keeper of the loaf’, > OE hla≠ford > ME loverd > MnE lord lady PrOE *hla≠f-d|ge > OE hlæ≠f-d|ge ‘bread (loaf) kneader’ > MnE lady (cf. OE da≠g ‘dough’, ME dogh) Fun Fun Facts Facts Hocus-pocus may come from Latin Hoc est corpus in the Mass (“This is the Body”) The “loo”: Garde à l’eau! Cinderella’s slipper was made of squirrel fur (Fr. vair ), but mistranslated by retellers poor in French (or who couldn’t afford fur) who thought it was verre, glass. Vulgus is Latin for crowd. Vulgar referred originally to non-nobles. French gentil gives us gentleman, gentility. Willy-nilly from OE wille nylle (contraction of ne wille) ‘if he wants or doesn’t want’ Hope Hope you you had had fun! fun!