* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Rehospitalizations and Direct Medical Costs for cSSSI: Linezolid

Survey

Document related concepts

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Staphylococcus aureus wikipedia , lookup

Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae wikipedia , lookup

Multiple sclerosis signs and symptoms wikipedia , lookup

Management of multiple sclerosis wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

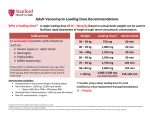

Original Research At a Glance Practical Implications p259 Author Information p 266 Full text and PDF www.ajpblive.com Web exclusive eAppendix Rehospitalizations and Direct Medical Costs for cSSSI: Linezolid Versus Vancomycin C. Daniel Mullins, PhD; H. Keri Yang, PhD, MPH; Eberechukwu Onukwugha, PhD, MS; Debra F. Eisenberg, PhD, MS; Daniela E. Myers, MPH; David B. Huang, MD, PhD; and Thomas P. Lodise, PharmD, PhD ABSTRACT Background: Patients hospitalized for complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSIs) are at risk for rehospitalization and high postdischarge costs. Objectives: To compare rehospitalization rates and total direct medical costs among cSSSI patients treated with linezolid or vancomycin after hospital discharge. Study Design: Two administrative claims databases were pooled to identify adult patients (aged 18-64 years) hospitalized for cSSSI and treated with linezolid or vancomycin. Patients with infective endocarditis, meningitis, bone/joint/device/implant infections, necrotizing fasciitis, or gangrene were excluded. Methods: Unadjusted rehospitalization rates and total direct medical costs within 42 days after discharge were compared between linezolid and vancomycin users in the full sample and a propensity score–matched sample. Multivariable regression analyses examined results after adjusting for confounders. Sensitivity analyses examined outcomes at 30 and 180 days. Results: Among 7260 patients hospitalized with cSSSIs, 42.6% (n = 3093) received linezolid and 57.4% (n = 4167) received vancomycin. While demographic and clinical characteristics were similar, vancomycin users had higher baseline comorbidities and longer length of stay during index hospitalizations. Multivariable regression indicated that linezolid was associated with 40% and 41% lower rates of all-cause rehospitalizations in the full and matched samples, respectively, and 45% lower rates of cSSSIrelated rehospitalizations in both samples. Linezolid was associated with cost savings of $1420 and $1708 per patient in the full and matched samples, respectively. Conclusions: Among commercially insured patients treated with either linezolid or vancomycin following hospital discharge for a cSSSI, linezolid was associated with significantly lower rehospitalization rates and total direct medical costs. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2013;5(6):258-267 C omplicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSIs) are infections that involve deeper layers of the skin, including the muscle and fascia. In the United States, there are an estimated 14 million outpatient (ie, physician offices, emergency and outpatient departments) healthcare visits for suspected Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections.1 Treatment of cSSSIs is complicated and often involves both surgery and intravenous antibiotics.2 Once considered a disease predominated by Streptococcus pyogenes, it is now estimated that more than half of all cSSSIs are due to Staphylococcus aureus, many of which are methicillin resistant.3-9 In a study of 11 emergency departments in the United States, approximately 76% of purulent (ie, containing pus) skin and soft tissue infections in adults were caused by S aureus.10 Of these infections, 78% were caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA); overall, MRSA caused 59% of skin and soft tissue infections. Given the increasing ubiquity of cSSSIs due to MRSA, 2 commonly prescribed empiric antibiotics are vancomycin and linezolid.11,12 Both linezolid and vancomycin are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cSSSIs caused by Gram-positive bacteria. These antibiotics are approved for patients with similar clinical characteristics, including patients with deep soft tissue infections, surgical/ traumatic wound infections, major abscesses, cellulitis, and infected ulcers and burns. The Infectious Diseases Society of America practice guidelines recommend both intravenous vancomycin and oral or intravenous linezolid 600 mg twice daily as first-line therapy for cSSSIs.13 To date, vancomycin and linezolid have been evaluated in a number of comparator-controlled cSSSI trials. Overall, the efficacy and safety of vancomycin versus linezolid for cSSSI due to MRSA have been comparable.14-16 Most recently, similar clinical and microbiologic success rates were found in a comparative clinical trial that assessed linezolid versus vancomycin for the management of noncellulitis cSSSI due to MRSA.17 258 The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits • November/December 2013 www.ajpblive.com Rehospitalizations and Direct Medical Costs While clinical trials have established the safety and efficacy of linezolid relative to vancomycin for cSSSI, many important questions remain. Patients enrolled in clinical trials may not be fully reflective of the diverse patient populations that use the drugs in clinical practice. Therefore, practice-level analyses are needed to ascertain the real-world effectiveness of linezolid relative to vancomycin in patients with cSSSIs. In addition, the primary outcomes assessed in cSSSI clinical trials center on clinical and microbiologic success rates at predefined times such as 1 to 2 weeks after the completion of therapy (ie, test-of-cure visit). To fully understand the clinical and economic implications of one therapy relative to another for cSSSIs, it is necessary to make a comprehensive assessment of real-world outcomes including healthcare utilization and rehospitalization and costs, in time frames beyond those typically seen in clinical trials. Such a comprehensive assessment, which examines healthcare utilization and costs across treatment groups, informs the decisionmaking processes of public and private insurers/payers and ultimately leads to increased patient health/utility and lower overall medical costs for the patient or society. Our previous study reported that patients who were treated with linezolid versus vancomycin after hospital discharge had lower rates of repeat hospitalization across an array of infection types; however, the prior study did not provide cost savings estimates.18 The current study aims to build upon our prior work using updated data from 2 administrative claims data sets (HealthCore Integrated Research Database and IMS PharMetrics database). This time, we examined both rehospitalization rates and total direct medical costs for patients treated with linezolid and patients treated with vancomycin following hospital discharge for a cSSSI from the perspective of a commercial insurer in the United States. METHODS Study Design This was a retrospective observational, comparative effectiveness drug study (Figure 1). The study design and analysis reflected the perspective of private insurers. The cSSSI cases were identified based on eligible hospitalizations occurring between January 1, 2007, and September 30, 2009. The index date was defined as the discharge date of the qualifying hospitalization. We examined baseline comorbidities, prior hospitalizations, and prior infections in the preindex period, which was defined as 180 days prior to the index hospitalization. A primary postindex period of 42 days (sensitivity analyses at 30 www.ajpblive.com PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS Complicated skin and skin structure infection (cSSSI) patients are at risk for rehospitalizations, which contribute to potentially avoidable wasteful healthcare spending. This study compared rehospitalization rates and total direct medical costs among cSSSI patients treated with either linezolid or vancomycin after hospital discharge. At a primary end point of 42 days, compared with vancomycin, linezolid was associated with: ■ ■ ■ Significantly lower rates of all-cause rehospitalizations (13% vs 22%; P <.01). Significantly lower rates of cSSSI-related rehospitalizations (8% vs 15%; P <.01). Significantly lower total direct medical costs (mean cost savings of $1420 per patient). and 180 days) from the discharge date of the qualifying hospitalization was used for comparing rehospitalizations and total costs, in accordance with our prespecified analysis plan. During the stage of developing our analysis plan, 42 days was specified as the primary end point for the analysis because based on the literature and clinical insight, most infections should resolve within a maximum of 6 weeks (ie, 42 days). Study Cohort The study population consisted of adult patients (aged 18-64 years) with a hospitalization related to cSSSI within either the HealthCore Integrated Research Database or the IMS PharMetrics database based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes used to define cSSSI. The codes used for the analyses are available in the eAppendix (available at www.ajpblive.com). Inclusion criteria required that patients be treated with either linezolid or vancomycin within 7 days of their hospital discharge. The following patients were excluded: patients who were enrolled in Medicare (because of unobserved Medicare claims data); patients who received oral vancomycin (because there is no systemic absorption of oral vancomycin, it is not used for treating cSSSIs); patients who had fewer than 3 days of linezolid oral therapy, in order to focus on those patients who experienced a therapeutic effect (there was no minimum day requirement for intravenous therapy because therapeutic drug levels are achieved after 1 dose); and patients with index hospitalizations longer than 30 days. In addition, patients with infections of the musculoskeletal system (codes 015.xx, 324.1, 376.03, 711.xx, 715.90, 715.98, 719.06, 722.9, 722.93, 726.65, 727.05, 727.09, 730. xx), endocarditis (code 424.9x), meningitis (codes 320.2, Vol. 5, No. 6 • The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits 259 ■ Mullins • Yang • Onukwugha • Eisenberg Figure 1. Study Design Schematic Patients must get study drugs within 7 days 180-day preindex period Index hospitalization 180-day postindex period Last date of follow-up Admission date of the index hospitalization Study index date = discharge date of the index hospitalization Outcomes were assessed at 30, 42, and 180 days 320.7, 320.8x), necrotizing fasciitis (codes 728.86, 729.4), gangrene (code 785.4), or prosthetic implant/device infections (codes 919.7, 996.6x, 999.3x) during the index hospitalization were excluded. These exclusion criteria were developed to facilitate a comparative study of linezolid versus vancomycin based on the FDA-approved linezolid indication for cSSSI.17 Outcomes and Study Variables The following outcomes were captured after discharge: all-cause rehospitalization and rehospitalization related to a cSSSI infection and total medical costs, which included index drug (ie, linezolid or vancomycin) costs; other drug costs; and inpatient, outpatient, and other costs such as laboratory and diagnostic costs. In accordance with our prespecified analysis plan, main analyses examined the outcomes at 42 days, while sensitivity analyses focused on the outcomes at 30 and 180 days following discharge. The covariate of interest was receipt of linezolid (vs vancomycin) as the index drug. The following potential confounders were examined and controlled for in multivariable regression models: sex, age at index discharge, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, length of stay of the index hospitalization, presence of bacteremia during the index hospitalization, presence of sepsis during the index hospitalization, use of other anti-MRSA antibiotics in the preindex period, presence of any infection-related hospitalization or infection-related outpatient physician visit in the preindex period, and presence of any all-cause hospitalization in the preindex period. The effect of CCI 260 The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits • November/December 2013 score was modeled using an ordered categorical measure (no comorbidity, 1 comorbidity, 2 comorbidities, 3 or more comorbidities) in both the rehospitalization and cost regression models. The rehospitalization and cost regression models included a continuous (linear) measure of age. The cost regression model also included a quadratic term to capture the nonlinear effect of age. Length of stay was dichotomized at the median value (5 days) in the rehospitalization regression model and was log-transformed in the cost regression model. All other variables entered as binary indicators of the factor described. Analyses A P value of .05 was used to determine statistical significance in hypothesis testing, and a P value of .10 was used in covariate selection. Descriptive analyses examined various characteristics of the study cohort. The χ2 and t statistics were used to test for significant differences in categorical and continuous variables, respectively, between linezolid and vancomycin users. A correlation matrix including all study variables was used to identify potential multicollinearity problems. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the adjusted odds of rehospitalization for linezolid versus vancomycin users. Prior to model specification, normality tests combined with quantile-quantile plots confirmed the suitability of the gamma distribution for the cost data. Following estimation of model parameters using a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution, the modified Park test19 confirmed the appropriateness of the gamma family www.ajpblive.com Rehospitalizations and Direct Medical Costs distribution for this analysis. A generalized linear model with log link was used to examine differences in total direct medical costs between linezolid versus vancomycin, after controlling for covariates. The covariates from the generalized linear model with gamma distribution provided input data for calculating the marginal effect (ie, the covariate-adjusted incremental cost for linezolid users compared with vancomycin users). The 95% confidence interval (CI) on the adjusted incremental cost was defined using the 5th and 95th percentiles of bootstrapped replicates (1000 runs). To address the potential for selection bias, we ran the aforementioned multivariable analyses in a propensity score–matched sample as well as in the full sample. The propensity score–matched sample was created by estimating the propensity of receiving linezolid as the index drug and then using a greedy algorithm macro written by Jon Kosanke and Erik Bergstralh of the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine to match cases with controls.20 The algorithm used a caliper width of 0.2 of the standard deviation (SD) of the logit of the propensity score, which is a function of the predicted propensity score, to conduct a 1-to-1 match. The following baseline characteristics were candidate variables for the regression model that estimated the propensity score: sex, age, length of stay of the index hospitalization, bacteremia during the index hospitalization, sepsis during the index hospitalization, CCI score, cancer at baseline, transplant, primary immunodeficiency disorders, human immunodeficiency virus, renal insufficiency, diabetes, hospitalization in the preindex period, and anti-MRSA antibiotics use in the preindex period; a forward selection approach was used to obtain the final set of variables for the regression equation. After the propensity score–matched sample was created, we compared the distribution of the propensity score between matched linezolid and vancomycin patients, examined standardized differences in observed baseline patient characteristics, and conducted individual variable and joint distribution significance testing. RESULTS Descriptive Analyses The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated with linezolid versus vancomycin are shown in Table 1. Of the 7260 patients with a cSSSI-related hospitalization in the full sample, 43% (n = 3093) initially received linezolid and 57% (n = 4167) initially received vancomycin after discharge. While patient characteristics were similar, those treated with vancomycin after discharge had more baseline comorbidities, longer hospital www.ajpblive.com stays, and higher rates of bacteremia during the index hospitalization relative to the linezolid users. The propensity score–matched sample consisted of 5920 patients with equal numbers in each treatment group and with no significant differences in examined baseline characteristics (Table 1). Results of bivariate rehospitalization comparisons are displayed in Figure 2. Unadjusted rehospitalization rates were lower for linezolid users compared with vancomycin users at each postdischarge time point assessed. At 42 days after discharge, treatment with linezolid versus vancomycin was correlated with significantly lower rates of all-cause rehospitalizations (13% vs 22%; P <.01) and cSSSI-related rehospitalizations (8% vs 15%; P <.01). Similarly, compared with vancomycin, linezolid use was associated with lower rates of all-cause and cSSSI-related rehospitalizations at day 30 (11% vs 19% and 7% vs 13%) and day 180 (24% vs 36% and 12% vs 21%), respectively. The differences were statistically significant in all cases (P <.01). Results of the unadjusted mean costs by cost category for patients treated with linezolid versus vancomycin are displayed in Figure 3. Index drug costs at 42 days after discharge were significantly higher for those treated with linezolid versus vancomycin ($1634 vs $375; P <.01); however, unadjusted total direct medical costs, inclusive of index drug costs, were significantly lower among patients treated with linezolid versus vancomycin ($6258 vs $10,066; P <.01). Similar results were found at 30 and 180 days after discharge (Figure 3). Multivariable Regression Analyses All-Cause Rehospitalization. After controlling for covariates (age, sex, CCI score, bacteremia, sepsis, length of stay during the index hospitalization, hospitalization or use of other anti-MRSA antibiotics in the preindex period), the use of linezolid versus vancomycin was associated with a lower odds of rehospitalization; linezolid use was associated with 40% lower odds of rehospitalization for any reason within 42 days of initial discharge (odds ratio [OR] = 0.60, 95% CI, 0.53-0.69; Table 2, full sample). Additional factors correlated with the odds of all-cause rehospitalization within 42 days included more comorbidities at baseline (OR = 1.35, 95% CI, 1.14-1.60 for CCI score of 1; OR = 1.95, 95% CI, 1.59-2.38 for CCI score of 2; OR = 2.55, 95% CI, 2.16-3.01 for CCI score of >3); having an index hospitalization longer than the median of 5 days (OR = 1.30, 95% CI, 1.13-1.48); and having an all-cause hospitalization in the preindex period (OR = 1.68, 95% CI, 1.47-1.90). The results were similar when Vol. 5, No. 6 • The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits 261 ■ Mullins • Yang • Onukwugha • Eisenberg Table 1. Cohort Characteristics by Study Drug Full Sample Matched Sample Vancomycin (n = 4167) Linezolid (n = 3093) P Vancomycin (n = 2960) Linezolid (n = 2960) P Male, n (%) 2115 (50.8) 1628 (52.6) .11 1516 (51.2) 1546 (52.2) .44 Age, y, mean ± SD 47.0 (11.1) 45.5 (11.5) <.01 46.0 (11.0) 46.0 (11.0) .53 Characteristics Demographics a Baseline comorbidities, n (%) CCI score <.01 .42 0 2010 (48.2) 1808 (58.5) 1665 (56.3) 1702 (57.5) 1 872 (20.9) 556 (18.0) 581 (19.6) 552 (18.7) 2 462 (11.1) 273 (8.8) 299 (10.1) 272 (9.2) >3 823 (19.8) 456 (14.7) 415 (14.0) 434 (14.7) Cancer 486 (11.7) 280 (9.1) <.01 259 (8.8) 275 (9.3) .47 HIV 22 (0.5) 43 (1.4) <.01 22 (0.7) 20 (0.7) .76 257 (6.2) 141 (4.6) <.01 121 (4.1) 141 (4.8) .21 1056 (25.3) 649 (21.0) <.01 649 (21.9) 648 (21.9) .97 Bacteremia during the index hospitalization, n (%) 162 (3.9) 79 (2.6) <.01 59 (2.0) 79 (2.7) .08 Sepsis during the index hospitalization, n (%) 228 (5.5) 158 (5.1) .5 138 (4.7) 153 (5.2) .37 Length of stay of the index hospitalization, days, mean ± SD 6.4 (4.6) 6.1 (4.2) <.01 6.0 (4.0) 6.0 (4.0) .78 2117 (50.8) 1249 (40.4) <.01 1252 (42.3) 1237 (41.8) .92 Hospitalization 1102 (26.5) 613 (19.8) <.01 650 (22.0) 603 (20.4) .13 Outpatient physician visit 2962 (71.1) 2232 (72.2) .31 2106 (71.2) 2121 (71.7) .67 Hospitalization or outpatient physician visit 3215 (77.2) 2368 (76.6) .55 2256 (76.2) 2256 (76.2) >.99 768 (18.4) 464 (15.0) <.01 453 (15.3) 457 (15.4) .89 Outpatient physician visit 2140 (51.4) 1684 (54.5) <.01 1544 (52.2) 1596 (53.9) .18 With anti-MRSA antibiotics use 1364 (32.7) 1228 (39.7) <.01 1087 (36.7) 1104 (37.3) .65 Renal insufficiency Diabetes Index hospitalization a Baseline utilization, n (%) With an inpatient admission With an infection-related: With a cSSSI infection-related: Hospitalization CCI indicates Charlson Comorbidity Index; cSSSI, complicated skin and skin structure infection; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SD, standard deviation. a Baseline period: 180 days prior to the admission date for the first qualifying hospitalization. examining all-cause rehospitalizations for linezolid versus vancomycin within 30 days (OR = 0.58, 95% CI, 0.50-0.67) or 180 days after discharge (OR = 0.65, 95% CI, 0.58-0.73). Table 2 (matched sample) further documents that linezolid was associated with reduced odds of repeat hospitalization in the subset of propensity score–matched patients. After controlling for covariates, using linezolid as initial treatment was associated with a 41% lower likelihood of rehospitalization for any reason within 42 days of initial discharge (OR = 0.59, 95% CI, 0.51-0.68). The results were similar when examining all-cause rehospitalizations within 30 days (OR = 0.56, 95% CI, 0.48-0.65) or 180 days after discharge (OR = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.59-0.74). 262 The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits • November/December 2013 cSSSI-Related Rehospitalization. After controlling for covariates, the use of linezolid compared with vancomycin was associated with a 45% lower likelihood of a cSSSI-related rehospitalization within 42 days of initial discharge (OR = 0.55, 95% CI, 0.47-0.64; Table 2, full sample). Individuals with 2 or more index comorbidities (OR = 1.57, 95% CI, 1.24-2.00 for CCI score of 2; OR = 1.92, 95% CI, 1.58-2.34 for CCI score of >3), an index hospitalization longer than the median of 5 days (OR = 1.21, 95% CI, 1.03-1.41), and any all-cause hospitalization in the preindex period (OR = 1.34, 95% CI, 1.15-1.56) had greater odds of rehospitalization with an ICD-9-CM code for cSSSI infection within 42 days of www.ajpblive.com Rehospitalizations and Direct Medical Costs Figure 2. Unadjusted Rehospitalization Rates for Patients Treated With Linezolid Versus Vancomycin Patients with an all-cause rehospitalization by period and index drug P <.01 P <.01 50 P <.01 36 40 30 22 19 20 24 13 11 10 P <.01 P <.01 P <.01 40 Percentage of All Percentage of All 50 Patients with a cSSSI-related rehospitalization by period and index drug 30 21 20 10 0 15 13 12 8 7 0 30 days 42 days 30 days 180 days 180 days 42 days Period Period Linezolid Vancomycin cSSSI indicates complicated skin and skin structure infection. Figure 3. Unadjusted Mean Costs by Cost Category for Patients Treated With Linezolid Versus Vancomycina Unadjusted Mean Costs 25,000 Ptotal <.01 20,000 $14,875 15,000 Ptotal <.01 Ptotal <.01 10,000 $7964 $10,066 $6258 $5256 5000 0 Pindex <.01 Pindex <.01 Linezolid Vancomycin 30-Day Costs Other a $22,705 Inpatient Linezolid Pindex <.01 Vancomycin Linezolid 42-Day Costs Outpatient Other (nonindex) drugs Vancomycin 180-Day Costs Index drugs P total compares the mean total costs for linezolid and vancomycin patients. P index compares the mean index drug costs for linezolid and vancomycin patients. discharge. The likelihood of having a cSSSI-related rehospitalization within 30 and 180 days was similar to that at 42 days after discharge. Linezolid use was associated with a 49% reduction in the odds of rehospitalization at 30 days (OR = 0.51, 95% CI, 0.43-0.61) and a 42% reduction at 180 days (OR = 0.58, 95% CI, 0.51-0.67) compared www.ajpblive.com with vancomycin use following discharge after index hospitalization. Table 2 (matched sample) shows that linezolid was associated with reduced odds of a cSSSI-related rehospitalization in the subset of propensity score–matched patients. After controlling for covariates, using linezolid Vol. 5, No. 6 • The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits 263 ■ Mullins • Yang • Onukwugha • Eisenberg Table 2. Association Between Linezolid Use and Odds of Postdischarge Rehospitalization and Incremental Cost Full Sample OR Variable 95% CI Adjusted OR Matched Sample 95% CI a Rehospitalization for Linezolid vs Vancomycin OR 95% CI 95% CI Adjusted ORa Rehospitalization for Linezolid vs Vancomycin Any all-cause rehospitalization within: 30 days 0.52 0.45-0.59 0.58 0.50-0.67 0.56 0.48-0.65 0.56 0.48-0.65 42 days 0.53 0.47-0.61 0.60 0.53-0.69 0.59 0.52-0.68 0.59 0.51-0.68 180 days 0.58 0.52-0.64 0.65 0.58-0.73 0.67 0.60-0.76 0.66 0.59-0.74 30 days 0.48 0.40-0.56 0.51 0.43-0.61 0.51 0.42-0.61 0.51 0.42-0.61 42 days 0.51 0.44-0.59 0.55 0.47-0.64 0.55 0.46-0.65 0.55 0.46-0.65 180 days 0.54 0.47-0.61 0.58 0.51-0.67 0.59 0.51-0.68 0.58 0.50-0.67 Any cSSSI-related rehospitalization within: Incremental Cost Savings for Linezolid vs Vancomycin Incremental Cost Savings for Linezolid vs Vancomycin MEa 95% CI Adjusted MEb 95% CI MEa 95% CI Adjusted MEa 95% CI 30 days $1154 $1123-$1184 $1003 $970-$1036 $920 $896-$945 $1254 $1211-$1297 42 days $1622 $1580-$1665 $1420 $1368-$1472 $1268 $1235-$1301 $1708 $1647-$1769 180 days $3336 $3249-$3423 $2539 $2436-$2641 $2333 $2272-$2394 $3157 $3031-$3284 Total medical and drug cost within: CI indicates confidence interval; cSSSI, complicated skin and skin structure infection; ME, marginal effect; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; OR, odds ratio. a Controlling for index drug, sex, age, Charlson Comorbidity Index score in preindex period, length of stay of the index hospitalization more than 5 days (the median), bacteremia during index hospitalization, sepsis during index hospitalization, any use of other anti-MRSA antibiotics in the preindex period, any infection-related hospitalization or infection-related outpatient physician visit in the preindex period, and any all-cause hospitalization in the preindex period. b The ME estimate calculates the incremental cost for linezolid users compared with vancomycin users. c Controlling for index drug, sex, age and age2, Charlson Comorbidity Index score in preindex period, logarithm of the length of stay of the index hospitalization, bacteremia during the index hospitalization, sepsis during the index hospitalization, any use of other anti-MRSA antibiotics in the preindex period, any infection-related hospitalization or infection-related outpatient physician visit in the preindex period, and any all-cause hospitalization in the preindex period. as initial treatment was associated with a 45% lower likelihood of cSSSI-related rehospitalization within 42 days of initial discharge (OR = 0.55, 95% CI, 0.46-0.65). The results were similar when examining cSSSI-related rehospitalization within 30 days (OR = 0.51, 95% CI, 0.42-0.61) or 180 days after discharge (OR = 0.58, 95% CI, 0.50-0.67). Total Direct Medical Costs After controlling for covariates, linezolid versus vancomycin use was associated with a mean cost savings of $1420 (95% CI, $1368-$1472) per patient within 42 days of discharge in the full sample and with a mean cost savings of $1708 (95% CI, $1647-$1769) per patient in the propensity score–matched sample (Table 2). The estimated cost savings over a 30-day postindex period were $1003 (95% CI, $970-$1036) in the full sample and $1254 (95% CI, $1211-$1297) in the propensity score– matched sample. The estimated cost savings over a 180day postindex period were $2539 (95% CI, $2436-$2641) 264 The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits • November/December 2013 in the full sample and $3157 (95% CI, $3031-$3284) in the propensity score–matched sample. DISCUSSION Several studies have evaluated the economic effect of linezolid compared with vancomycin in the treatment of skin and skin structure infections, including cSSSIs, and these are described in the medical literature.14,21-29 In these studies, linezolid compared with vancomycin therapy was generally associated with a decrease in intravenous therapy days14,23,25 and length of stay.14,21,23-25 Linezolid therapy appeared to either decrease costs25-27 or at least be cost neutral29 compared with vancomycin for the treatment of cSSSIs, including those caused by MRSA. Although clinical trials have established the efficacy of linezolid relative to vancomycin for cSSSI, there is still a major need for clinical and economic comparative data in the diverse patient populations that use these www.ajpblive.com Rehospitalizations and Direct Medical Costs drugs in clinical practice. For cSSSIs that require hospitalization, rehospitalization rates and postdischarge costs are significant concerns from both a public health and a payer perspective. Unfortunately, these data are not well captured from cSSSI registration trials. According to the CMS, 20% of all readmissions occur within 30 days of discharge and 76% of these readmissions may be preventable.30 Beyond the clear public health implications, these potentially preventable high readmission rates are particularly concerning given the recent nosocomial infection policy initiative within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; it will refuse to pay for additional costs associated with selected nosocomial infections that are “reasonably preventable.”31 In light of the need for real-world comparative effectiveness data, this study compared rehospitalization rates and total direct medical costs among commercially insured adult patients with cSSSIs treated with either linezolid or vancomycin after hospital discharge. Data were compared across 2 large national administrative claims databases. The results of the rehospitalization analyses indicated that receipt of linezolid was associated with an approximate 40% lower odds of a rehospitalization; the exact estimate of lower odds varied from 35% to 49% according to length of follow-up (30, 42, and 180 days postdischarge) and whether all-cause or cSSSI-related rehospitalizations were examined. These results are similar to our previous administrative claims analysis that pooled 21 unique infection types.18 In that study of 11,018 hospitalized patients, linezolid was associated with a lower OR of repeat infection-related hospitalization in patients with pneumonia, S aureus, and skin infections. For patients with skin infections, linezolid was associated with a reduction of 27% in the odds of infection-related hospitalization relative to vancomycin. When we examined the full sample of 21 infection types, the number needed to treat with linezolid instead of vancomycin to avoid a rehospitalization was 14. For the current study, the number needed to treat with linezolid versus vancomycin was 11 or 15 to avoid a repeat hospitalization, depending on whether the analysis considers all-cause or cSSSI-related hospitalizations. Although rehospitalization costs were not calculated, we did examine the rates of rehospitalization and saw that linezolid use was associated with significantly lower rates. The current study also showed that use of linezolid versus vancomycin as the index drug for patients hospitalized with cSSSI may be associated with significantly lower total costs of care (including rehospitalization costs) compared with postdischarge vancomycin. The current study also showed an adjusted lower total www.ajpblive.com direct cost savings per patient between $1003 and $2539 for patients treated with linezolid versus patients treated with vancomycin. In the multivariable regression analysis that controlled for potential confounders, these lower total direct medical costs were consistent at 30, 42, and 180 days. These results are similar to those published by McKinnon and colleagues.26 Using data from a clinical trial comparing linezolid with vancomycin for the treatment of cSSSIs due to suspected or proven MRSA, the mean ± SD cost for intent-to-treat population patients (n = 717) treated with linezolid versus vancomycin was $4865 ± $4367 versus $5738 ± $5190, respectively (difference, $873; P = .02); in the MRSA population it was $4881 ± $3987 versus $6006 ± $5039, respectively (difference, $1125; P = .04). A separate administrative claims database study by McKinnon and colleagues showed similar findings.22 In a cSSSI subgroup, mean ± SD healthcare costs were greater for patients receiving vancomycin compared with those receiving linezolid (vancomycin, $9244 ± $14,244; linezolid, $7794 ± $16,910; P = .12), and the rate of relapse or rehospitalization was lower for patients receiving linezolid compared with those receiving vancomycin (OR = 0.70, 95% CI, 0.35-1.40).22 The findings in this study should be interpreted in the context of a number of important limitations of observational studies. First, this study reflects nonrandom assignment based upon real-world clinical use of linezolid versus vancomycin. Thus, selection bias may impact the reported findings. Furthermore, we utilized administrative claims data, which are collected for payment purposes rather than research. Therefore, the presence of a claim for a drug does not guarantee the actual administration of the drug; the data do not capture the dispensing of a drug sample; and data may be missing if all the claims are not submitted by providers. Second, this administrative claims database study lacked patient clinical information (eg, incision and drainage procedures), including mortality. Instead of culture results, ICD-9-CM codes were used to determine the presence of infection. Furthermore, administrative claims data do not allow us to look at the specific type of infection, bacterial etiology (eg, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus versus MRSA), and antimicrobial susceptibility of the cultured bacteria. Third, we were not able to control for unobservable patient, provider, and insurance benefit design characteristics that would further impact selection bias regarding prescription of linezolid or vancomycin, or for confounding by indication. Selection bias may be a particular issue if linezolid is prescribed to patients with certain demographic Vol. 5, No. 6 • The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits 265 ■ Mullins • Yang • Onukwugha • Eisenberg characteristics or higher socioeconomic status because of the greater cost and patient cost sharing for linezolid. However, to limit the impact of selection bias, we controlled for certain observable characteristics including age, sex, CCI score, bacteremia during the index hospitalization, length of stay of the index hospitalization, and any use of other anti-MRSA antibiotics in the preindex period. We also replicated our analyses in a subset of patients who were matched using a propensity score–matching algorithm, and the results were similar for those analyses. Finally, information regarding the antibiotics received during the index hospitalization was not available. In addition to the described limitations, it is important not to extend the findings beyond our study population of nonelderly patients with private insurance, because they are not necessarily representative of all nonelderly, privately insured patients in the United States. The strength of this study is the large number of patients included in this pooled database (n = 7260). The data were consistent across different definitions of rehospitalization and total direct medical costs when evaluated at 30, 42, and 180 days following discharge. Patients prescribed linezolid after hospital discharge had significantly lower rates of all-cause and cSSSI-related rehospitalization, and lower total direct costs compared with patients receiving vancomycin for cSSSI. In an era when value-based medical purchasing and reduction in wasteful spending are major considerations in health policy, such data provide valuable evidence for hospital administrators and payers. This is particularly true in infectious diseases, where avoidable readmissions may not be reimbursed. CONCLUSION Among commercially insured patients with a cSSSIrelated hospitalization, the use of linezolid versus vancomycin as the index drug following hospital discharge was associated with significantly higher antibiotic drug costs. However, linezolid use was associated with statistically significant lower total direct medical costs, including the index drug costs, compared with vancomycin use. Furthermore, linezolid was associated with significantly lower rehospitalization rates than vancomycin in both unadjusted comparisons and multivariable analyses that controlled for age, sex, CCI score, bacteremia, sepsis, length of stay during the index hospitalization, prior hospitalization, or use of other anti-MRSA antibiotics in the preindex period. Results were consistent across the various postdischarge end points examined and across 266 The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits • November/December 2013 study samples (ie, full unmatched and propensity score– matched samples). Acknowledgments The authors wish to acknowledge support from Kaloyan Bikov, Diane McNally, and the Pharmaceutical Research Center at the University of Maryland for data management and analytic support; Christy Fang and HealthCore Inc, for providing data and analytic support; IMS for providing data; and Richard Chambers of Pfizer Inc for statistical support. Editorial support was provided by Lisa Blatt, MA, from the University of Maryland. Author Affiliations: From Pharmaceutical Health Services Research (CDM, HKY, EO), University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, MD; HealthCore Inc (DFE), Wilmington, DE; Pfizer Inc (DEM), formerly of Pfizer Inc (DBH), Collegeville, PA; Albany College of Pharmacy (TPL), Albany, NY. Funding Source: This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Drs Mullins and Onukwugha are employees of the University of Maryland, which received research funding from Pfizer in connection with conducting this study and development of this manuscript. Dr Yang was an employee of the University of Maryland when the study was conducted. Dr is an employee of HealthCore Inc, which received research funding from Pfizer in connection with conducting this study and development of this manuscript. Dr Huang is a former employee of Pfizer Inc in connection with this study and development of this manuscript. Dr was a paid consultant to Pfizer as an employee of Lodise & Lodise LLC in connection with this study and the development of this manuscript. Author Disclosures: Dr Mullins has served as a consultant and scientific advisor to Pfizer Inc and has received consulting income and research grants from Pfizer. In addition, he has received consulting income and/or grant support from Amgen, Bayer, BMS, Cubist, Eisai, Genentech, GSK, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Otsuka, and sanofi-aventis during the past 3 years. Dr Onukwugha has received consulting fees and research grants from Pfizer Inc. Dr Eisenberg is a salaried employee of HealthCore Inc. Ms Myers is a salaried employee and shareholder of Pfizer Inc. Dr Huang was an employee and shareholder of Pfizer Inc at the time the study was conducted. Dr Lodise is a consultant for Pfizer, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, and Forest; a speaker for Pfizer, Forest, and Cubist Pharmaceuticals; and has received grant support from Astellas, Cubist, and Pfizer. Authorship Information: Concept and design (CDM, HKY, DE, DEM, DBH, TPL); acquisition of data (CDM, DE, DEM); analysis and interpretation of data (CDM, HKY, EO, DE, DEM, DBH, TPL); drafting of the manuscript (CDM, EO, DBH); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (CDM, EO, DE, DEM, DBH, TPL); statistical analysis (CDM, HKY); provision of study materials or patients (DE); obtaining funding (CDM, DEM); administrative, technical, or logistic support (CDM, DEM); and supervision (CDM, DEM). Address correspondence to: C. Daniel Mullins, PhD, Professor, Pharmaceutical Health Services Research Department, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, 220 Arch St, 12th Fl, Baltimore, MD 21201. E-mail: [email protected]. REFERENCES 1. Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1585-1591. 2. US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: developing drugs for treatment: draft guidance. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ Guidances/ucm071185.pdf. Published August 2010. Accessed November 12, 2011. 3. Nichols RL. Optimal treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44(suppl A):19-23. 4. Wright BM, Eiland EH. Retrospective analysis of clinical and cost outcomes associated with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and skin structure infections treated with daptomycin, vancomycin, or linezolid. http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jpath/2011/347969/. J Pathogens. 2011:1-6. Accessed November 12, 2011. 5. Jenkins TC, Sabel AL, Sarcone EE, Price CS, Mehler PS, Burman WJ. Skin and www.ajpblive.com Rehospitalizations and Direct Medical Costs soft-tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):895-903. 6. Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, Stilwell MG, Fritsche TR. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998-2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57(1):7-13. 7. Weigelt JA, Lipsky BA, Tabak YP, Derby KG, Kim M, Gupta V. Surgical site infections: causative pathogens and associated outcomes. Am J Infect Control. 2010; 38(2):112-120. 8. Talan DA, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al; EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft-tissue infections in US emergency department patients, 2004 and 2008. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(2): 144-149. 9. Yates C, May K, Hale T, et al. Wound chronicity, inpatient care, and chronic kidney disease predispose to MRSA infection in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(10):1907-1909. 10. Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al; EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):666-674. 11. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285-292. 12. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(3):319]. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):e18-e55. 13. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections [published corrections appear in Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(12):1830 and Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(8):1219]. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373-1406. 14. Itani KM, Dryden MS, Bhattacharyya H, Kunkel MJ, Baruch AM, Weigelt JA. Efficacy and safety of linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of complicated skin and soft-tissue infections proven to be caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Surg. 2010;199(6):804-816. 15. Stevens DL, Herr D, Lampiris H, Hunt JL, Batts DH, Hafkin B. Linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(11):1481-1490. 16. Weigelt J, Itani K, Stevens D, Lau W, Dryden M, Knirsch C; Linezolid CSSTI Study Group. Linezolid versus vancomycin in treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(6):2260-2266. 17. Drugs.com. Zyvox. http://www.drugs.com/pro/zyvox.html. Revised May 2013. Accessed January 3, 2012. 18. Mullins CD, Hsu VD, Cooke CE, Shelbaya A, Wallace AE, Perencevich EN. Rehospitalization rates among linezolid versus vancomycin users. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2011;3(2):e1-e13. www.ajpblive.com 19. Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20(4):461-494. 20. Faries DE, Leon AC, Haro JM, Obenchain RL. Analysis of Observational Health Care Data Using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2010. 21. Sharpe JN, Shively EH, Polk HC Jr. Clinical and economic outcomes of oral linezolid versus intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of MRSA-complicated, lower-extremity skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Surg. 2005;189(4):425-428. 22. McKinnon PS, Carter CT, Girase PG, Liu LZ, Carmeli Y. The economic effect of oral linezolid versus intravenous vancomycin in the outpatient setting: the payer perspective. Manag Care Interface. 2007;20(1):23-34. 23. Itani KM, Weigelt J, Li JZ, Duttagupta S. Linezolid reduces length of stay and duration of intravenous treatment compared with vancomycin for complicated skin and soft tissue infections due to suspected or proven methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;26(6):442-448. 24. Lipsky BA, Itani KM, Weigelt JA, et al. The role of diabetes mellitus in the treatment of skin and skin structure infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: results from three randomized controlled trials. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(2):e140-e146. 25. McCollum M, Sorensen SV, Liu LZ. A comparison of costs and hospital length of stay associated with intravenous/oral linezolid or intravenous vancomycin treatment of complicated skin and soft-tissue infections caused by suspected or confirmed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in elderly US patients. Clin Ther. 2007;29(3):469-477. 26. McKinnon PS, Sorensen SV, Liu LZ, Itani KM. Impact of linezolid on economic outcomes and determinants of cost in a clinical trial evaluating patients with MRSA complicated skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(6): 1017-1023. 27. Patanwala AE, Erstad BL, Nix DE. Cost-effectiveness of linezolid and vancomycin in the treatment of surgical site infections. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(1): 185-193. 28. Li JZ, Willke RJ, Rittenhouse BE, Rybak MJ. Effect of linezolid versus vancomycin on length of hospital stay in patients with complicated skin and soft tissue infections caused by known or suspected methicillin-resistant staphylococci: results from a randomized clinical trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2003;4(1):57-70. 29. Bounthavong M, Hsu DI, Okamoto MP. Cost-effectiveness analysis of linezolid vs. vancomycin in treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft tissue infections using a decision analytic model. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):376-386. 30. National Priorities Partnership, convened by the National Quality Forum. Preventing Hospital Readmissions: A $25 Billion Opportunity. http://www.qualityforum.org/NPP/docs/Preventing_Hospital_Readmissions_CAB.aspx. Published November 2010. Accessed February 1, 2013. 31. Graves N, McGowan JE Jr. Nosocomial infection, the Deficit Reduction Act, and incentives for hospitals. JAMA. 2008;300(13):1577-1579. Vol. 5, No. 6 • The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits 267 ■ Mullins • Yang • Onukwugha • Eisenberg eAppendix. ICD-9-CM Codes and Descriptions Used for Identification and Inclusion of Patients With Complicated Skin and Skin Structure Infections Infection Group ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Codes Cellulitis, abscess, mastitis 567.31, 675.10, 675.11, 675.13, 675.14, 675.20, 675.23, 675.24, 681, 681.0, 681.00, 681.01, 681.02, 681.1, 681.10, 681.11, 681.11, 681.9, 682, 682.0, 6821, 682.2, 682.3, 682.4, 682.5, 682.6, 682.7, 682.8, 682.9 Chronic ulcer infection 707.1, 707.10, 707.11, 707.12, 707.13, 707.14, 707.15, 707.19 Postoperative infections 998.5, 998.59, 998.83 Other local infections of skin and subcutaneous tissue 686, 686.0, 686.00, 686.09, 686.8, 686.9, 728.0 Acute lymphadenitis 683 ICD-9 -CM indicates International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. a268 The American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits • November/December 2013 www.ajpblive.com