* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Commentary on an Attic Black Figure Lekythos, Ure Museum inv

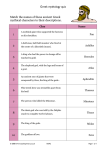

Ancient Greek warfare wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Pontic Greeks wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

History of science in classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Greek mythology wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek religion wikipedia , lookup

Commentary on an Attic Black Figure Lekythos, Ure Museum inv. 51.4.9 By Matthew Welch The pot chosen for this essay is a 6th century Attic black figure lekythos that has been attributed to the Painter of Vatican G 31.1 According to the Ure Museum database, the scene painted on the lekythos depicts Herakles and two other Greeks fighting against three Amazon warriors. This essay will contextualise this piece through an examination of both the images it displays and its creation. If we begin with the shape and purpose of the object, we see that it includes the features that are conventionally associated with lekythoi, such as its narrow neck, small mouth and single vertical handle. Lekythoi were generally used as containers for oil or precious liquids such as perfume, and thus were probably used by women in the gynaecium and by men in the gymnasium. They were also used to make offerings of perfume to the dead, though the lekythos being studied here would not have been used for funerary purposes as funerary lekythoi used polychrome on a white ground and had their own distinctive iconography.2 Also, many had false bottoms so that they could be filled up with a relatively small amount of perfume. Lekythoi were also used as gifts for the bride in marriage ceremonies, though this too is unlikely to have been the purpose of our lekythos as it was usual to decorate such gifts with scenes of brides and home life in order to link the object with the wedding.3 The scene depicted on a vase may not be able to tell us anything about what it was actually used for, with the possible exception of vases used at specific occasions. Apart from funerary and marriage vases, there is not necessarily any correlation between vases and the images with which they are decorated.4 Painters, it would seem, decorated their vases with great freedom and paid little attention to their function. Even though the images on the lekythos may not tell us anything about its 1 John D. Beazley, Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters (Oxford 1956) 486.5; see also John D. Beazley, Paralipomena (Oxford 1971) 222. 2 C. Bron and F. Lissarague in A City of Images (Princeton 1989) 18. 3 B. A. Sparkes, Greek Pottery. An Introduction (Manchester 1991) 77. 4 Bron and Lissarague 1989, 21. intended use, however, they are still worth examining to see if they can reveal any information about Greek society at the time. As mentioned above, the images on the lekythos appear to depict Herakles and two Greeks fighting against three Amazon warriors. The amazons were a mythical race of warrior women who were said to originate in an area near the Black Sea. The Greek explanation of their name, meaning ‘breast-less’, comes from stories of them removing one breast in order to allow easier use of the javelin or bow.5 This, however, is never represented in art and as such is not featured on the lekythos. They have been depicted on vases wearing both heavy and light armour, and fighting with an axe, spear, javelin or Scythian bow. On the lekythos they can be identified by their highcrested helmets and the fact that they are armed with spears and circular shields. What, then, can the presence of these Amazon warriors on the lekythos tell us about Greek society? William Blake Tyrrell notes that myths were considered by the Greeks to be a source of instruction, as they could guide choice by presenting actions with known outcomes for imitation or avoidance (Tyrrell 1986, 1). He claims that the Amazon myth was formed out of cultural ideas about aspects of society such as sex, war, politics and the rites affecting the journey from infancy to adulthood and marriage (Tyrrell 1986, xiii). Classical Athens was a patriarchal society that idealised the adult male warrior. In order for that ideal to exist, boys had to become fathers and warriors, while the girls had to become mothers and wives. Marriage caused a considerable amount of tension in Greek households, however, when it came to giving a daughter away or receiving one into the family. Tyrrell states that Greek households thought very highly of the notion of independence, but that notion would always be impossible to completely obtain because every house had to give away its daughters in order to receive others for its sons (Tyrrell 1986, 27). Thus society had an inescapable situation where daughters had to be exchanged, despite suspicion of women brought into households and jealousy over independence, in order to prevent houses from dying out. The Amazon myth, Tyrrell claims, was there to explain that this situation was necessary by reversing it to show how dangerous attempting to change it would be. 5 W. Blake Tyrrell, Amazons A Study in Athenian Mythmaking (Baltimore 1986) 49. The image on this lekythos has long been taken as a depiction off the Amazons fighting against the Greek hero Herakles. The myth of Herakles contains only one episode involving Amazons, so there is no question over which of his labours or deeds is portrayed on the lekythos. It is during his ninth task set for him by Eurystheus that Herakles fought against the Amazons, as he had to bring back the belt of the Amazonian queen, Hippolyte. Some versions have him travelling to the Amazon homeland on his own, though in others he is accompanied by a small army. The lekythos appears to side with the latter, as other Greek warriors are depicted in addition to Herakles. Thomas H. Carpenter notes that Herakles’ expedition to the Amazon homeland became the second most popular labour with Attic black-figure vase painters, as is testified by its appearance on nearly four hundred vases.6 Tyrrell reports that there may have been a political reason for this, as Pisistratus, the tyrant of Athens from 545 to 527 B.C., aimed to identify himself with Herakles as the favourite of Athena. Only circumstantial evidence of this exists, though, such as Pisistratus’s return from exile in a chariot driven by a woman dressed as Athena being very reminiscent of Herakles’ introduction to Olympus by Athena (according to Herodotos). It is worth noting, however, that we do not know for certain that the heroic figure on the lekythos is indeed Herakles. Sparkes notes that the mass appeal of mythological stories meant that most were presented in a straightforward way, with the characters often having their names written nearby and being made identifiable by their own personal attributes (Sparkes 1991, 19). Herakles’ usual attributes were his lion skin and club, but neither of these can be found on the lekythos. If the figure is not Herakles, then who else could it be? The Amazons were always portrayed as being highly skilled opponents, and only heroes were capable of defeating them in combat, as is illustrated on the lekythos by the killing of a Greek warrior by an Amazon. It might therefore depict one of the other Greek heroes, but which one? Achilles and Theseus were also said to have fought against the Amazons, so could it be either of these two instead? 6 T.H. Carpenter, Art and Myth in Ancient Greece (London 1994) 25. If we look first at Achilles, we know that he was said to have fought against the Amazons who had come to the aid of Priam’s city in the Trojan War. The most famous incident from this is where he looks into the eyes of Penthesilea and falls in love with her just as he pierces her with his sword. One example of another painter’s treatment of this scene is the London B 210 neck amphora by Exekias.7 Here, the spear is shown to penetrate her neck and draw blood, something which rarely happens in images of Heraklean battles and is not to be found on the lekythos. Also of note is the obvious eye contact between to the two figures, which is central to this scene. This too is not present on the lekythos, which suggests that this is not the scene being portrayed as the key elements are missing. What about Theseus then? His involvement with the Amazons comes from a story of him travelling to the home of the Amazons and kidnapping their queen, or, in other versions, travelling there as a part of Herakles’ expedition and being given Hippolyta as a reward. The latter version can be found on the Athenian treasury at Delphi (Tyrrell 1986, 4). Regardless of how he acquires her, the Amazons were said to have laid siege to Athens in an attempt to get her back, but they were beaten back with the aid of Hippolyta, though some versions say that a treaty ended the conflict instead. Whenever Theseus’s expedition is portrayed, the focus appears to always be on him carrying off Hippolyta (or Antiope), as that is the central action of this part of the myth. The Amazon queen though, is not featured on the lekythos so it is unlikely to represent the trip to the Amazon homeland. What about the later part, when Theseus is defending Athens from the Amazon attack then? One immediate reaction would be that there is nothing in the scene to indicate that the battle is being fought inside a city. Rainer Maria Rilke, however, noted that the architecture of cities, as well as the seas, plains and mountains did not exist as a frame for human activities in art at that time.8 Landscape and still life were almost unknown so the city of Athens would not have been portrayed as a part of the scene anyway. If the scene does depict the defence of Athens then that would explain the presence of the other Greek soldiers, who, as mentioned earlier, did not go on either Theseus’ or Herakles’ expeditions in 7 Dietrich von Bothmer, Amazons in Greek Art (Oxford 1957) 72. some versions of the myths. Unfortunately, although Carpenter states that this battle between the Amazons and the Athenians was a popular subject with sculptors and painters throughout the fifth century, this was after, not during, the time around which the lekythos was created (Carpenter 1994, 164). Although it is possible that any of these heroes could be depicted in the scene, it seems that the most likely candidate is probably still Herakles. Carpenter notes that although he is usually bearded, he did begin to appear as a beardless youth towards the end of the sixth century (Carpenter 1994, 118). The fact that he almost always wears a lion skin means that there were exceptions and this could well be one of them. What perhaps is most convincing though is the apparent popularity of Herakles with Athenians during the latter half of the sixth century (Carpenter 1994, 117). While he does note that Theseus’s popularity as a subject for Attic vase paintings grew near that of Herakles, Carpenter notes that this did not happen until the very end of the sixth century (Carpenter 1994, 160). Carpenter goes on to say that only his fight with the Minotaur appears with any regularity on Attic black figure vases. Therefore, at least statistically, it is more likely to be a representation of Herakles rather than Theseus, and we have already noted that Achilles is an unlikely answer. In conclusion then, the lekythos appears to be one of many hundreds of Greek pots that depicted Herakles fighting against a mythical warrior race of women who were invented to justify the institution of marriage. It was a tremendously popular theme for vase painters and, as noted earlier, it can tell us little about what the lekythos was actually used for, except that it negates the possibility of it being used in marriage or funeral rites as such pieces had their own unique iconography. The lekythos, then, retains some element of mystery about its intended purpose. 8 C. Berard and J.-L. Durand in A City of Images (Princeton 1989) 30.