* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Anticancer therapy education programme

Survey

Document related concepts

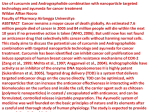

Transcript