* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Battle of Antietam

Second Battle of Corinth wikipedia , lookup

Anaconda Plan wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Red River Campaign wikipedia , lookup

East Tennessee bridge burnings wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Chancellorsville wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Shiloh wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Sailor's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Perryville wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Wilson's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Namozine Church wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Cumberland Church wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Lewis's Farm wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

First Battle of Bull Run wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Cedar Creek wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Harpers Ferry wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Malvern Hill wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Roanoke Island wikipedia , lookup

Eastern Theater of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Northern Virginia Campaign wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fredericksburg wikipedia , lookup

Battle of New Bern wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Seven Pines wikipedia , lookup

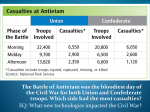

AMERICAN PUBLIC UNIVERSITY SYSTEM Charles Town, West Virginia McClellan’s Failure at Antietam Submitted By Anthony F. Bevilacqua Student: 4144616 HIST552 A002 Sum 11 Submitted to the Department of History 16 October 2011 1 The Battle of Antietam stands as the bloodiest single day of fighting in the whole of the Civil War and still stands as the costliest day in all of American history in terms of American lives, lost, maimed, and missing. This horrific battle also has the stigma of being a virtual stalemate despite the fact it was considered a Union victory. The Union victory in this battle is what precipitated the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation by Lincoln, a turning point in the war politically. But, at the heart of it, the Union victory was hollow and specious. The Union was only able to declare victory because the Confederate Army retreated from the field at the end of the day, giving the Union the victory under the rules of war as they stood. However, the Union could have achieved almost total victory over the Confederacy during this battle had it not been for the decisions made by General George B. McClellan. Through the inadequate leadership of McClellan, the battle would be a strategic victory at best and nowhere near the tactical victory that Washington was expecting out of the diminutive General when he sent a message to President Lincoln stating, “Will send you trophies.”1 His grandiose promises never did live up to what he actually delivered during the battle that day near Sharpsburg, Maryland. Some would later argue it could even be considered a narrow tactical victory for the Confederacy.2 General McClellan believed he had the enemy right where he wanted them, and had he executed an all out battle, he may have carried the day. But, it would not be the lack of fight in the men that cost the Union the victory that day. Instead McClellan’s poor planning along with his irrational husbanding of fresh troops during critical stages of the battle will be shown as the 1 United States Government: War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Vol. 19, part 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), 281. 2 Gary W. Gallagher, ed., The Antietam Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 5. 2 ultimate cause of the failure of the Union to achieve total tactical victory over the Confederacy. McClellan’s faith in the wrong men, and his distrust of the men that may have been able to get the job done also compounded the errors at Antietam. Shelby Foote would note that the battle was so disorganized from a Union standpoint that it progressed as three separate battles, instead of one coordinated effort as it should have.3 This disorganization was the tool that most favored the small Army that General Robert E. Lee had at his command and because of it he was able to easily shift his small numbers where they were needed time and time again, thwarting the Union effort. McClellan would be unable to think quickly and force a large scale attack during the battle as he should have; being on the constant worry that he would be soon routed by the forces he believed were set against his individual Corps. In fact, many historians note that General McClellan had a constant worry that he was facing superior forces with insufficient troops.4 This thesis does support the works of Stephen W. Sears and James McPherson who shared the opinion of Ezra A. Carman who wrote, “more errors were committed by the Union commander than in any other battle of the war.”5 The thesis could argue that McClellan was a proud, vainglorious man. However, simply reading from his personal correspondence or his memoirs shows that McClellan was a man caught up in his own legend. He had extreme confidence in his own appearance and abilities but little faith in his subordinates or his superiors for that matter. He was a borderline incompetent that would be eventually exposed by his utter 3 Shelby Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative: Fort Sumter to Perryville (New York: Random House, 1958), 693. 4 Maurice G. D’Aoust, “Unraveling the Myths of Burnside Bridge.” Civil War Times 46, Iss. 7 (2007), 50-51.; Bevin Alexander, Robert E. Lee's Civil War (Avon, MA: Adams Media, 1998), 107.; Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (New Haven: Ticknor & Fields, 1983), 23, 174. 5 Ezra Ayers Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman's Definitive Account of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam. Edited by Joseph Pierro (New York: Routledge, 2008), 363. 3 lack of battlefield sense. On the day these two armies met in Maryland, just outside of Sharpsburg, the Union Army had approximately 72,000 armed troops compared to the 27,000 men General Lee had at his disposal; however McClellan believed he faced a vastly superior army with almost 100,000 troops.6 But, McClellan also had fore knowledge of the disposition of General Lee’s forces through the discovery of Special Order 191, lost by a Confederate courier and discovered in a field by Union troops.7 Yet the Union failed to achieve tactical victory during the main portions of the battle, before heavy fighting would dictate the maneuverings of forces on both sides. The main problem with McClellan’s overall battle strategy is in that he lacked the vision and the coordination to accomplish the feat he had set out in his mind. From the way he deployed his forces to the way he controlled them throughout the battle it is apparent that he and he alone believed he could win the battle through his use of strategy, but instead of fighting an overall campaign McClellan managed to turn one single battle into three much smaller battles and therefore more manageable for Confederate forces. These battles would break down into the approximate time frames: Daybreak to 9 am, 9 am to 1 pm, and 1 pm to sunset. McClellan would not commit the entire force at once, but bit by bit, managing the entire battle as if the individual commanders were puppets for him to maneuver, without the necessary sense to command their own troops. Had he committed his forces en masse, or allowed his commanders some autonomy he might have been able to overwhelm the rebel forces through sheer numbers, superior firepower, or ingenious tactics. However, before McClellan’s errors during the battle 6 Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 174. Ibid., 112. James M. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 107. Gary W. Gallagher, Antietam: Essays on the 1862 Maryland Campaign (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1989), 61. 7 4 can be broken down, his errors before the battle should be clearly explained. The biggest cause for confusion during the Battle of Antietam would not have to do with any troop movements or unit fighting, but by McClellan’s own positioning during the battle. McClellan would position his headquarters at the farm house of Phillip Pry. This observation station was almost two miles from where the fighting was to commence that morning, and although on high ground it did not have a commanding view of the battlefield. In fact, McClellan would only be able to view the central portion of the battlefield, but neither flank to include the Rohrbach Bridge.8 How could McClellan ever hope to wage a successful battle against the Confederates when he would not be able to discern what was going on at the flanks of the battle? He would only be able to issue orders on information coming to him through couriers on the state of the battle and trust it was going as planned. This location would be a great defensive position for the little Napoleon if the Confederates were to break through. However, the Confederates were aligned in defensive positions, so this should have not been a concern for McClellan. But, ever the cautious man, he would place himself firmly out of harm’s way. However, this position would only serve to distance him from the troops, and from the battle. This would also slow down communication as any change in orders would have to be couriered over two miles to the commander he wanted to address. By the time any meaningful communication could be achieved, the focus of the battle could have shifted, and indeed did during points in the battle. Strong defenses might be exposed, weak areas shored up, a line of men routed. All in all this was a poor way for McClellan to lead and was not a great start for him, already predisposed to being overly cautious. On top of this, McClellan would spend the entire afternoon of September the 16th staging his troops for the battle to come on the next day, 8 Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 195, 217-218. 5 orchestrating troop movements throughout the afternoon and late into the night. This would cause General Lee to guess exactly where the battle would open the next day.9 When the battle opened at daybreak the next morning, this distance, limited visibility, and announcement of his opening intentions would only be the start of his many errors. The next great errors were to come as he deployed his forces piecemeal for the first stage of the battle. In McClellan’s own words his plans for the next day were: “to attack the enemy’s left with the corps of Hooker and Mansfield, supported by Sumner’s and, if necessary, by Franklin’s; and as soon as matters looked favorably there, to move the corps of Burnside against the enemy’s extreme right, upon the ridge running to the south and rear of Sharpsburg, and, having carried their position, to press along the crest towards our right; and whenever either of these flank movements should be successful, to advance our centre with all the forces then disposable.”10 This may have been a seemingly adequate plan, if executed with precision and coordinated well, but this would prove to be too difficult for McClellan to manage from a distance. As the sky signified the transition from night to day sometime before 6 am, McClellan ordered the opening attack. It would be General Joseph Hooker’s I Corps that started the fighting that day coming out of the North Woods down the Hagerstown Turnpike towards the East Woods where the Confederate soldiers were positioned. The troops under Hooker’s command numbered about eight thousand six hundred men. McClellan would attack what he believed to be a 100,000 plus man army with a little less than twelve percent of his entire strength. With the number of Confederate troops he believed he would be facing it is hard to imagine what was going through his mind when he sent nothing more than an expeditionary force to engage them. His goal was to roll up the Confederate flank, yet he held the XII Corps 9 Ibid., 175-177. Ellen McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story: The War for The Union, The Soldiers Who Fought It, The Civilians Who Directed It, and His Relations to it and to Them (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887), 590. 10 6 in reserve. The unsupported I Corps would ultimately meet the Confederates in the Cornfield where dozens of regiments fought and the firing was so thick and furious that, “…every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as with a knife.” Hooker’s forces fought for the greater part of an hour and a half until nearly 7 am, while General Stonewall Jackson and General Lee sent fresh divisions into the fighting. The XII Corps would continue to sit by idly. They did not enter the battle for nearly two hours, but when their seven thousand two hundred man troop was ordered to enter the fray, their commander General Mansfield, fresh to combatant command, would march them in column formation into the battle. Mansfield would continue to lead men into the battle, but without adequate briefings from the I Corps he became confused as to what was going on and inadvertently exposed himself to enemy fire, getting killed.11 Had these corps engaged the Confederates at the same time they might have avoided the confusion that resulted in the death of Mansfield that morning. As the battle raged on, units from the Union met with limited success near Dunker Church when a division of the XII Corps made a breakthrough in the Confederate defensive line. But, by that time Hooker was out of the fight having been wounded through the foot and the advance failed12. Had there been any senior leadership in the field, the Union may have been able to exploit this breakthrough. Although both Hooker and Mansfield may have been removed by enemy fire regardless of when they entered the battle, staggering the participation would have no added benefit for McClellan’s plan. At 9 am, the advance from the north end of the battlefield had been halted. The Union troops withdrew and moved their lines to a more advantageous position. Had 11 Marion V. Armstrong, Jr., Unfurl Those Colors! McClellan, Sumner, and the Second Army Corps in the Antietam Campaign (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2008), 169. 12 Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 203-205. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom, 118-119; Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 181-191. 7 McClellan attacked with all of those forces at once, he probably could have overwhelmed the rebels. But, by sending them in bit by bit, never over committing any of his troops he failed to do anything except to chew up two good corps. It was at this time as the Union troops of the I Corps were pulling back from the carnage that was the Cornfield, the battle was shifting to the center of lines and the second skirmish would kick off at 9am. At 7:20 am, General Edwin Sumner’s II Corps had been ordered to support the sluggishly advancing attacks by the I and XII Corps. However, it wasn’t until 9am that Sumner’s forces were in position. By all accounts, Sumner was a headstrong commander and McClellan kept him on a short leash. Perhaps McClellan should have put Sumner’s II Corps in reserve with him instead of General John Fitz Porter’s V Corps, where he could keep an eye on him. But, McClellan put a commander in the field that he was not sure of. With the loss of Mansfield and Hooker, fate would deal the cards and Sumner would be in command by default. Again, McClellan’s poor planning, sub-par leadership and inability to position his commanders correctly would lead to more blunders. Sumner would show up on scene with his own pre-conceived notions of the battle and launch his troops straight into the grinder with no thought. General Alpheus Williams of the XII Corps would attempt to brief him but was repulsed by Sumner. Sumner’s plan was simple. They were to come through the East Woods across the Cornfield, which had been pulled back from by both sides, and rout the Confederates in the West Woods. However, General Sedgwick’s division of the II Corps was caught in an ambush and out flanked; taking fire from the side and the rear, the division retreated. The II Corps other two divisions continued south and encountered Confederate troops on a sunken road, what is now known as the Bloody Lane,13 where the engagement was sharp and furious. The fighting continued there for 8 almost four hours and the Union troops finally broke through around 1 PM. The confederate troops, who had been in a strong position, retreated through a misunderstanding. It was this that could have changed the battle for the Union yet again. The Confederates were now being slaughtered and were in disarray but yet no follow up was made by Union troops. All that was left was for the Union to exploit this mistake. But, clearly the stranglehold of McClellan’s command was felt here as well. Sumner sent a courier to McClellan in which he told him that General Franklin’s VI Corps was the only organized command left on the field. Franklin would argue for the chance to exploit the center of the Confederates, Sumner would argue against it.14 McClellan would take the advice of the General that wanted to broach no offensive and listened to Sumner. He did this despite the fact he had the 10,300 fresh troops of General John Fitz Porter’s V Corps and three thousand five hundred, to this point unused, cavalry troops. His failure to use any reserves is only further proof of the cautious and lackluster offensive McClellan was willing to hazard in order to win the day. The Confederates were poised to be routed, yet nothing ever came of this as the focus of the battle would shift to the southern point of the battlefield at the Rohrbach Bridge. The blunder of the Rohrbach Bridge would be the main focus of the third stage of the battle from 1 pm to sunset. Although this objective was supposed to have been taken during the mid-morning, it was not taken until late in the afternoon. In reality this portion of the battle should have commenced at daybreak with the other battles. But McClellan wanted to hold these troops until he believed success could be achieved. McClellan would initially admit the order for Burnside to attack was not sent until around 10 a.m., but would later revise this number to 8 a.m. 13 Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 220-221. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom, 122. 14 Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative, 695.; Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 271. 9 in order to distance himself from the failure at Antietam. Burnside, on the other hand, would claim the order did not arrive until around 10 a.m. Later historians would lay the blame on Burnside for that gap between the crucial hours of 8 and 10 a.m. when they supposed the order did arrive. There is then only one reason there was disparity in the official recounting of the battle, simply McClellan was mistaken. In an 1876 letter from General D. B. Sackett regarding that day and those orders in question wrote, “at about nine o’ clock on the morning of the battle of Antietam, you told me to mount my horse and to proceed as speedily as possible with orders directing General Burnside to move his troops across the bridge or stream in his front…” In fact, the order is titled the 9:10 order. This meant that given the time from the penning of the order to the arrival of the order may have take about fifty minutes, if one considers the rigors of delivering a message from one side of a battle front where McClellan placed himself to the other in the heat of hostilities. The fact the order arrived about 10 a.m. is backed by the fact in the same letter General Sackett stated that after he arrived, he stayed with Burnside for three hours until the bridge was taken, which was known to occur around 1p.m.15 Historians have also laid blame on Burnside for not directing his troops to cross the creek and take the bridge. Some historians, like Bruce Catton, believe this could have been done easily. This belief is based on a quote by Henry Kyd Douglas, an officer on Stonewall Jackson’s staff, who said, “Go look at it [the bridge] and tell me if you don’t think Burnside and his corps might have executed a hop, skip, and a jump and landed on the other side. One thing is certain, Ellen McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story: The War for The Union, The Soldiers Who Fought It, The Civilians Who Directed It, and His Relations to it and to Them (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887), 609.; Perry D. Jamieson, Death in September: The Antietam Campaign (Abilene, TX: McWhitney Foundation Press, 1999), 94.; Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, 235.; McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story, 609. 15 10 they might have waded it that day without getting their waist belts wet in any place.” Bruce Catton was to rely on that statement in his indictment of Burnside which is a large part of the blame that has been attached to him since then and used by other historians to prove Burnside’s incompetence, deflecting criticism from McClellan. However, Douglas’s statement has a twofold problem, the first being that he was wrong about the creek and in reality the creek was most likely impassible and the bridge became the only safe way across. In fact, McClellan recounted in his official report that, “Antietam creek at this point is a sluggish stream, with few fords and those difficult of crossing.”16 As the only mention of the creek depth that day comes from Douglas, a Confederate officer, who never even approached the creek, we cannot suppose to know what the conditions of the creek were that day. McClellan dispatched Captain James Duane, an expert who had written the manual on crossing rivers as part of troop movements to ascertain the accessibility of the crossing at Snavely’s Ford and to read the river. McClellan arrived on the scene to inspect Burnside’s preparations and position his troops, a fording point having been chosen almost two thirds of a mile downstream of the bridge. The second problem with Douglas’ glib statement is that in all reality, no one hops, skips, and jumps across anything during a barrage of minié balls and cannon fire from a protected position. This is notable when one considers that Burnside would have to send the bulk of his twelve thousand man corps across a bridge only twelve feet wide and one hundred twenty-five William Marvel, “More than Water Under Burnside’s Bridge.” America's Civil War 18, Iss. 6 (2006), 46. Bruce Catton, Mr. Lincoln’s Army (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1954), 361. Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode with Stonewall (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940), 172.; William Marvel, “Sculpting a Scapegoat.” America's Civil War 20, Iss. 4 (2007), 46.; Augustus Woodbury, Major General Ambrose E. Burnside and the Ninth Army Corps: A Narrative in the Campaigns in North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee During the War for the Preservation of the Republic (Providence: Sidney S. Rider & Brother, 1867), 133. 16 11 feet long. Not only was the bridge open to direct and enfilade fire, but the road leading to the bridge was also within range as it ran parallel to the river for a distance. McClellan told Burnside he would need to take the bridge at some point in the morning on the seventeenth and would wait until directed to attack, Burnside agreed to that assignment. But other than that it seems that McClellan himself became unsure how he would use the IX Corps, as he contradicted his own ideas to their dispersement no less than three times in reports one month then one year after the battle.17 McClellan should have ordered the IX Corps into battle much earlier in the day, as he had no reliable way of knowing how long it would take them to cross the bridge, especially with the statement about the creek being hard to ford. On the taking of the Bridge, men of the 2nd of 20th Georgia regiments were defending the bridge from a protected tree line. What the Union troops could not have known was that geographically speaking the tree line these men occupied was an almost naturally fortified position. The terrain at Antietam Creek has a topography of deeply dissected limestone and shale formations, making for extremely broken ground surface and steeper slopes which contrast with the surrounding area largely made up of gently rolling hills.18 This would allow the Georgians to entrench themselves in such a way that would make digging them out very costly indeed. But this attack was only meant to be a diversion as over three thousand two hundred troops were to cross the river at the spot McClellan’s engineers had chosen and then come up on the flank of the Georgians. With the fighting intense along the bank of the river, Captain John Griswold attempted to lead his company directly across the river but the men were shot down 17 James V. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and the Maryland Campaign of 1862 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965), 268-269. 18 Judy Ehlen and R.C. Whisonant, “Military geology of Antietam battlefield, Maryland, USA--geology, terrain, and casualties.” Geology Today 24, Iss. 1 (2008), 27. 12 and finally the 11th Connecticut was forced to retreat.19 The troops that were to cross the ford found the site utterly unusable, the banks were steep and there was a one hundred sixty foot high bluff on the federal side. How McClellan’s engineers ever selected this site is the ultimate question, but select it they did. It is hard to fault Burnside or McClellan for this mistake. But as the commander of the army, the fault should lay with McClellan as it was his troops that picked the inadequate crossing site for Burnside’s forces. When the bridge was finally secured over five hundred Union troops were killed. The men were exhausted and nearly out of ammunition and powder. They made their way slowly over the bridge. This action would tie up the men of the IX Corps until approximately 3:00 p.m. and they would make no further advancement that day as when they were finally positioned to advance, the Confederate counterattack with A.P. Hill’s reinforcements arrived from Harper’s Ferry, some of them dressed in captured Union uniforms.20 This would spell the end of the Union offensive from the Rohrbach Bridge. However it should be noted that McClellan would only employ 20,000 troops at any given time during the battle and upwards of 20,000 fresh troops would not fire a shot at all that day.21 Perhaps if McClellan had not kept his fresh troops in reserve all day long he would have been able to back General Burnside’s advance so when the IX Corps had taken the bridge they could stand aside and let fresh troops past them to continue the attack, rather than try and reassemble and continue after several long hours fighting. Ultimately, McClellan lacked the vision that a true commander of troops and armies Robert Barr Smith, “Killing Zone at Burnside’s Bridge.” Military History 21, Iss. 2 (2004), 37.; Phillip Thomas Tucker, Burnside’s Bridge: The Climactic Struggle of the 2nd and 20th Georgia at Antietam Creek (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000), 84.; Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, 262-263.; Smith, “Killing Zone at Burnside Bridge.” Military History, 37. 20 Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 289. 21 McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom, 116. 19 13 needs to possess. Instead of fighting a battle for the express purpose of defeating an enemy force, it is apparent that time and time again during the Battle of Antietam that McClellan would be fighting each small battle on an extremely limited and myopic scale. He was content to control his commanders from a distance, feeding in forces a little at a time hoping that he could achieve success and recognition through a victory that he manipulated into being. His limited view and distance from the battle kept him from effectively coordinating any true total offensive against the enemy. Additionally, his style of limited engagement during the course of the day instead of an all out offensive allowed the rebels to shift troops to meet his tentative probing. By denying his commanders the autonomy that any commander needs on a battlefield he squandered any opportunity to rout the Confederate forces and win a true tactical victory on that day in September. Remaining content to simply not lose any ground to an enemy that was already entrenched in a defensive position seems to have been the oxymoronic goal of the commander of the Army of the Potomac that day. Afterwards, he would claim victory simply because the Confederates chose to leave the field of battle that day, for a simple desire to end the carnage. This pyrrhic victory would come because of McClellan’s flaccid leadership and inability to think as a tactician and strategist rather than a politician. When questions arose about the lack of success during the overall battle, McClellan would lay blame on his subordinates; men that he had not allowed to do any commanding of their own that day. Truly the Battle of Antietam says more about McClellan’s shortcomings as a commander than it does about the will of the forces that clashed on that day. 14 Works Cited Alexander, Bevin. Robert E. Lee's Civil War. Avon, MA: Adams Media, 1998. Armstrong, Marion V., Jr. Unfurl Those Colors! McClellan, Sumner, and the Second Army Corps in the Antietam Campaign. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2008. Carman, Ezra Ayers. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman's Definitive Account of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam. Edited by Joseph Pierro. New York: Routledge, 2008. Catton, Bruce. Mr. Lincoln’s Army. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1954. D’Aoust, Maurice G. “Unraveling the Myths of Burnside Bridge.” Civil War Times 46 Iss. 7 (2007): 50-57. Douglas, Henry Kyd. I Rode with Stonewall. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940. Ehlen, Judy and R.C. Whisonant. “Military geology of Antietam battlefield, Maryland, USA--geology, terrain, and casualties.” Geology Today 24, Iss. 1 (2008): 20-27. Foote, Shelby. The Civil War, A Narrative: Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Random House, 1958. Gallagher, Gary W. Antietam: Essays on the 1862 Maryland Campaign. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1989. ____________., ed. The Antietam Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999. Marvel, William. “More than Water Under Burnside’s Bridge.” America's Civil War 18, Iss. 6 (2006): 46-52. ____________. “Sculpting a Scapegoat.” America's Civil War 20, Iss. 4 (2007): 42-47. Jamieson, Perry D. Death in September: The Antietam Campaign. Abilene, TX: McWhitney Foundation Press, 1999. McClellan, Ellen. McClellan’s Own Story: The War For The Union, The Soldiers Who Fought It, The Civilians Who Directed It, and His Relations to it and to Them. New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887. 15 McPherson, James M. Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Murfin, James V. The Gleam of Bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965. Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. New Haven: Ticknor & Fields, 1983. Smith, Robert Barr “Killing Zone at Burnside’s Bridge.” Military History 21, Iss. 2 (2004): 3440. Tucker, Phillip Thomas. Burnside’s Bridge: The Climactic Struggle of the 2nd and 20th Georgia at Antietam Creek. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. United States Government. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. 19, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Woodbury, Augustus. Major General Ambrose E. Burnside and the Ninth Army Corps: A Narrative in the Campaigns in North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee During the War for the Preservation of the Republic. Providence: Sidney S. Rider & Brother, 1867.