* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

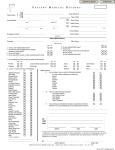

Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors: Working to Improve Medication Safety Prepared by pharmacist Eman Elayeh Introduction Almost everyone in the modern world takes medication at one time or another Most of the time medications are beneficial But some occasion they do harmful effects (side effects) → adverse drug events, which is inevitable But sometimes the harm is caused by an error in prescribing or dispensing or taking medication 2 Multiple Factors Since 1992, the Food and Drug Administration has received nearly 30,000 reports of medication errors. These are voluntary reports, so the number of medication errors that actually occur is thought to be much higher. There is no "typical" medication error, and health professionals, patients, and their families are all involved. Some examples: 3 Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors Examples 1. A physician ordered a 260-milligram preparation of Taxol for a patient, but the pharmacist prepared 260 milligrams of Taxotere instead. Both are chemotherapy drugs used for different types of cancer and with different recommended doses. The patient died several days later, though the death couldn't be linked to the error because the patient was already severely ill. 4 Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors Examples 2. An older patient with rheumatoid arthritis died after receiving an overdose of methotrexate--a 10-milligram daily dose of the drug rather than the intended 10milligram weekly dose. Some dosing mix-ups have occurred because daily dosing of methotrexate is typically used to treat people with cancer, while low weekly doses of the drug have been prescribed for other conditions, such as arthritis, asthma, and inflammatory bowel disease. 5 Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors One patient died because 20 units of insulin was abbreviated as "20 U," but the "U" was mistaken for a "zero." As a result, a dose of 200 units of insulin was accidentally injected. A man died after his wife mistakenly applied six transdermal patches to his skin at one time. The multiple patches delivered an overdose of the narcotic pain medicine fentanyl through his skin. A patient developed a fatal hemorrhage when given another patient's prescription for the blood thinner warfarin. 6 Definitions and terminology Preventable ADE” is harm caused by the use of a drug as a result of an error (e.g., patient given a normal dose of drug but the drug was contraindicated in this patient). These events warrant examination by the provider to determine why it happened. “Non-Preventable ADE” is drug-induced harm occurring with appropriate use of medication (e.g., anaphylaxis from penicillin in a patient and the patient had no previous history of an allergic reaction). While these are currently nonpreventable, future studies may reveal ways in which they can be prevented. 7 8 Scenario/case studies Case 1. A 25 kg child with no prior history of penicillin allergy was prescribed 250 mg orally of amoxicillin suspension twice daily (morning and evening) for 7 days. On the seventh day, the child inadvertently received a morning dose of 500 mg instead of 250 mg. The child did not suffer any negative consequences from the error Medication error resulting in no harm 9 Scenario/case studies Case 2. A 74 year old female with acute leg pain presented to the emergency department. She has a history of sleep apnea. She has no previous history of opioid use. Prescriber ordered hydromorphone 2 mg IV. Patient found unresponsive in respiratory distress with SP O2 at 70. Naloxone administered. A preventable ADE (medicationrelated harm due to error) 10 Scenario/case studies Case 3. A 37 year old patient diagnosed with an infection for which amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium is a clinically reasonable choice. Patient has used amoxicillin and other antibiotics in past without adverse eff ects. Prescriber ordered amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium 500 mg every 12 hours. After taking 3 doses, patient experienced rash and facial swelling. He was transported to the emergency department and treated. A Non-preventable ADE (medicationrelated harm not due to error) 11 Scenario/case studies Case 4. A 19 year-old male presented with a severe infection for which treatment with a beta lactam antibiotic is the drug of choice with no good clinical alternative. In the past, this patient developed a maculopapular rash to penicillin. The prescriber, with input from an infectious disease expert, considered the risk-benefit of using a beta lactam antibiotic and concluded that it was the best choice in spite of the previously reported ADE. An order for a beta lactam antibiotic was initiated with close monitoring of the patient to quickly identify an allergic reaction if one manifested. On day 3 of therapy, the patient developed a maculopapular rash and the decision was made to provide symptomatic treatment of the rash and continue therapy with the beta lactam antibiotic 12 13 Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors These and other medication errors reported to the FDA may stem from poor communication; misinterpreted handwriting; drug name confusion; confusing drug labels, labeling, and packaging; lack of employee knowledge; and lack of patient understanding about a drug's directions. "But it's important to recognize that such errors are due to multiple factors in a complex medical system," says Paul Seligman, M.D., director of the FDA's Office of Pharmacoepidemiology and Statistical Science. "In most cases, medication errors can't be blamed on a single person 14 Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors A medication error is "any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer," according to the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. The council, a group of more than 25 national and international organizations, including the FDA, examines and evaluates medication errors and recommends strategies for error prevention. 15 Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors It is difficult to estimate how often preventable adverse drug events occur. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Preventing Medication Errors estimated that 1.5 million preventable adverse drug events occur each year in the United States. Another study estimated that 530,000 preventable adverse drug events occur each year among outpatient Medicare beneficiaries. The annual cost of treating preventable adverse drug events in Medicare enrollees aged 65 and older is estimated at $887 million 16 Patient information Having accurate patient information is the first priority in medication safety, as it guides physicians to choose the appropriate medication, dose, route and frequency. The following tips can assist your practice in this area. 17 Patient information Use patient-specific identifiers. To help ensure that the right patient receives the right medication, instruct your staff to use at least two patient-specific identifiers, such as the patient's name and date of birth, when administering medications. Your practice should also have a “name alert” process to identify patients with the same or similar names. This could include a “name alert” sticker for the chart or a highlighted name alert for an electronic health record (EHR). 18 Patient information Verify allergies and reactions. While this may seem like a “no-brainer,” it is often a neglected step in the medication process. Your practice should have a protocol that requires a clinical staff member to ask about allergies and reactions to medications, latex and food (e.g., egg allergies for some vaccines) before any prescriptions, samples or office-administered medications are given to the patient. Include the information on the front of a paper chart (e.g., with an allergy label), on the top of each progress note page or on the EHR screen. When documenting allergies and other medication-related information, avoid using abbreviations or truncated names for the medications (e.g., PCN or HCTZ), as these can be easily misread. 19 Patient information Highlight critical diagnoses and conditions. Four important diagnoses have a significant impact on medication selection, dosing and frequency. They are diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, liver disease and psychiatric disease. Whether you use paper or electronic charts, put a system in place to highlight these conditions for easy reference when medications are administered or prescribed. In addition, when prescribing teratogenic medications to female patients of childbearing age, document either their negative pregnancy test results or the education you provided regarding the need for effective birth control. It's also important to highlight patients' smoking status and alcohol consumption, as these factors may affect medication selection, dosing and frequency. 20 Patient information Update current medications. A current medication profile listed in a standard prominent location on each patient's chart can be an important safety measure. This should be updated at each visit and should include a reminder to ask not only about prescription drugs but also over-the-counter medications, herbal medicines, supplements and vitamins. Structure the medication list to require that the drug, dose, route, frequency and purpose be recorded for each medication, herbal or vitamin. 21 Update current medications Indication DRUG NAME Dose Frequency Route Herbs/supplements / vitamins 22 Patient information Standardize height and weight measurements. ISMP recommends that health care professionals record information in metric units, which are commonly used in medication labeling and package inserts, as a way to standardize measurement. An easy reference chart for conversion of inches/pounds to metric measures can be made available in each exam room, nursing station, etc. Simplify weights using the following formula: If the weight is less than 2 kg, carry out weight to two decimal places; if the weight is 2 kg to 10 kg, carry out the weight to one decimal place; if the weight is greater than 10 kg, round to the nearest whole number. 23 Drug information Maintain drug references. It is unrealistic to expect any physician can be conversant on the tens of thousands of prescription and over-the-counter medications on the market. To help decrease risk to patients, make sure that all staff members who prescribe, dispense, administer or provide patient education on medications have easy access to current drug information and other decision support resources. Decide on a core set of drug information references that will be used (e.g., Drug Facts and Comparisons) and update them at least yearly or whenever a new edition is available. In addition, consider using personal digital assistants with frequently updated drug information software (e.g., Epocrates, lexi drug information). 24 Drug information Identify high-alert meds. Practices should identify a list of “high-alert” medications that require extra precautions when administered, prescribed, dispensed or refilled. High-alert medications are those that have a propensity to cause serious patient harm when used in error. They include warfarin, low-molecular-weight heparins, insulin and oral agents for diabetes, opiates and methotrexate. ISMP has compiled a list of 14 high-alert medications as well as a list of 19 high-alert drug classes/categories, which can be found online at http://www.ismp.org/Tools/highalertmedications.pdf . 25 High alert medications: Warfarin management Lack of dosing guidelines and lack of appropriate monitoring can lead to serious harm associated with this class of medications. In a study by Bates et al., anticoagulants accounted for 4% of preventable ADEs and 10% of potential ADEs. A literature review by Kanjanarat et al. reports that anticoagulation therapy is associated with serious and frequent ADEs in both inpatients and outpatients. Warfarin and insulins, both of which typically require ongoing monitoring to prevent overdose or toxicity, caused one in every seven estimated ADEs treated in emergency departments (14.1%; 95% confidence interval 9.6% to 18.6%); and more than a quarter of all estimated hospitalizations (871 cases, 95% confidence interval 17.3% to 35.2%). In the elderly, insulin, warfarin, and digoxin were implicated in one in every three estimated ADEs treated in emergency departments (1,592 cases, 33.3%; 95% confidence interval 27.8% to 38.7%); and 41.5% of estimated hospitalizations (646 cases, 95% confidence interval 32.4% to 50.6% 26 High alert medications: Warfarin management Warfarin is commonly involved in ADEs for a number of reasons. These reasons include the complexity of dosing and monitoring, lack of patient adherence, numerous drug interactions, and dietary interactions that can affect drug activity. Strategies to improve both the dosing and monitoring of these high-alert medications have potential to reduce the associated risks of bleeding or thromboembolic event 27 High alert medications: Warfarin management Suggested Changes: Because warfarin has such a narrow therapeutic index, appropriate dosing and monitoring are critical. Since ongoing therapy occurs in the ambulatory setting, it is essential to engage patients by ensuring that they understand how to take the medication, which other medications should be avoided, and how to identify symptoms that indicate harm. Include a nutrition consult to educate patients on warfarin about drug/food interactions. Develop a robust communication plan to share information and to ensure timely follow-up with the next provider of care when a patient is discharged from the hospital. 28 High alert medications: Warfarin management Changes Designed to Ensure Standardization: Standardize protocols and dosing: Standardize protocols for the initiation and maintenance of warfarin therapy including Vitamin K dosing guidelines. Develop a protocol, based on evidence, to discontinue and restart warfarin perioperatively. Develop a protocol, based on evidence, to bridge warfarin therapy with more rapidly acting anticoagulants such as heparin and LMWH. Make information available; for example, improve access to lab results and/or use of point-of care testing in order to determine doses. Initiate patient self-testing of their INR and self-adjustment of their doses. Ensure appropriate monitoring, patient education, follow-up, and dose management through a centralized anticoagulation service. 29 Drug information Identify high-alert meds Similarly, practices can refer to the Beers list when prescribing medications for older adults. This is a list of 48 individual medications or classes to avoid in patients over 65 years of age because the risk is unnecessarily high and safer alternatives exist. The Beers list includes daily fluoxetine (Prozac) because of its long half-life and risk of producing excessive stimulation to the central nervous system and increasing agitation; nonCOX-selective NSAIDs because of their potential to produce gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure, high blood pressure and heart failure; muscle relaxants because they are poorly tolerated by the elderly and cause anticholinergic adverse effects, sedation and weakness; and large doses of short-acting benzodiazepines (Ativan, Xanax, etc.) because seniors are especially sensitive to them. 30 Drug information 31 Communication Share information. Practices must promote an “equal team member” concept where communication flows in all directions. This encourages all physicians and staff to be vigilant and to detect and act on potential error signals, rather than dismissing them. Physicians can model this behavior simply by asking their nurses, medical assistants and others for input and by sharing information with other team members on a regular basis. 32 Drug information Improve your handwriting. A 1979 study estimated that one-third of physicians' handwriting was illegible. Presumably little has changed over the years. To ensure that your orders and prescriptions are legible, try printing rather than using cursive, sit rather than stand when writing and work in what safety experts describe as a “sterile cockpit” (a quiet area for writing). 33 Drug information Avoid problematic abbreviations. The FDA and ISMP in July 2006 embarked on a joint campaign to eliminate the use of potentially confusing abbreviations, symbols and dose designations in various forms of medical communication. These abbreviations, symbols and dose designations have proven to be a barrier to effective communication and have resulted in significant harm to patients. For example, instead of writing “QD,” which is often misread as QID, it is recommended that health care professionals spell out the word “daily.” 34 Drug information 35 Drug information Be aware of similar drug names. Handwritten medication prescriptions can be difficult to interpret , particularly if they involve medications that have similar names such as Isordil – Plendil, Celebrex – Cerebyx, Lamictal – Lamisil, and Zyprexa – Zyrtec – Zantac. Many, if not all, of these drugs with similar names carry different indications for use; therefore, including the indication with the medication can reduce confusion. The prescription pad shown in this article contains check boxes for common indication categories that can help communicate the purpose of the medication being prescribed. For example, if a physician were prescribing Zyrtec, he or she would check the box next to “allergic/immunologic.” 36 Drug information 37 38 Drug information Require that orders be read back. Orders given verbally, rather than in written form, are inherently problematic because of different dialects and accents, misinterpretations of names and strengths, etc. The key to a safe process is using “read back.” The staff member should record the order directly onto the prescription pad/order sheet/computer as the prescriber is relaying it and then should read back the information to the prescriber. The prescriber should request the read back if it is not offered. During this process, spell the drug name and strength of the medication. For example, errors have been reported when the number 15 has been misinterpreted as 50. Always say “one five” for 15 or “five zero” for 50. 39 Labeling and storage Separate problematic drugs. Do not store drugs with look-alike names or similar packaging in close proximity to each other in the medication storage area, exam medication storage area, exam rooms or sample closet. Alphabetized drug storage can cause inadvertent mix-ups. In addition, segregate any “high-alert” medications that may be used in the practice (e.g., sedating agents or anesthetics). Separate and use auxiliary labels for different vaccines, tuberculin purified protein derivatives (PPD) and other injectable products that may be confused. ISMP has reported on several mix-ups with PPD being given in place of vaccines and vice versa. Separate external solutions, non-drug items, testing solutions, reagents and chemicals from internal products. External products such as benzoin and podophyllin should be labeled “for external use only.” Hemoccult developers and glucose monitoring chemicals have been mistakenly used as eye drops. 40 41 42 43 Sound a like medications 44 Sound a like medications 45 See error prone abbreviations document See sound a like medications document 46 47